Chapter 1

Introduction to Reinforcement Learning

"Reinforcement learning, at its core, is about learning from interaction. As we build more sophisticated agents, our ability to model and optimize complex decision-making processes will transform industries." — Richard Sutton

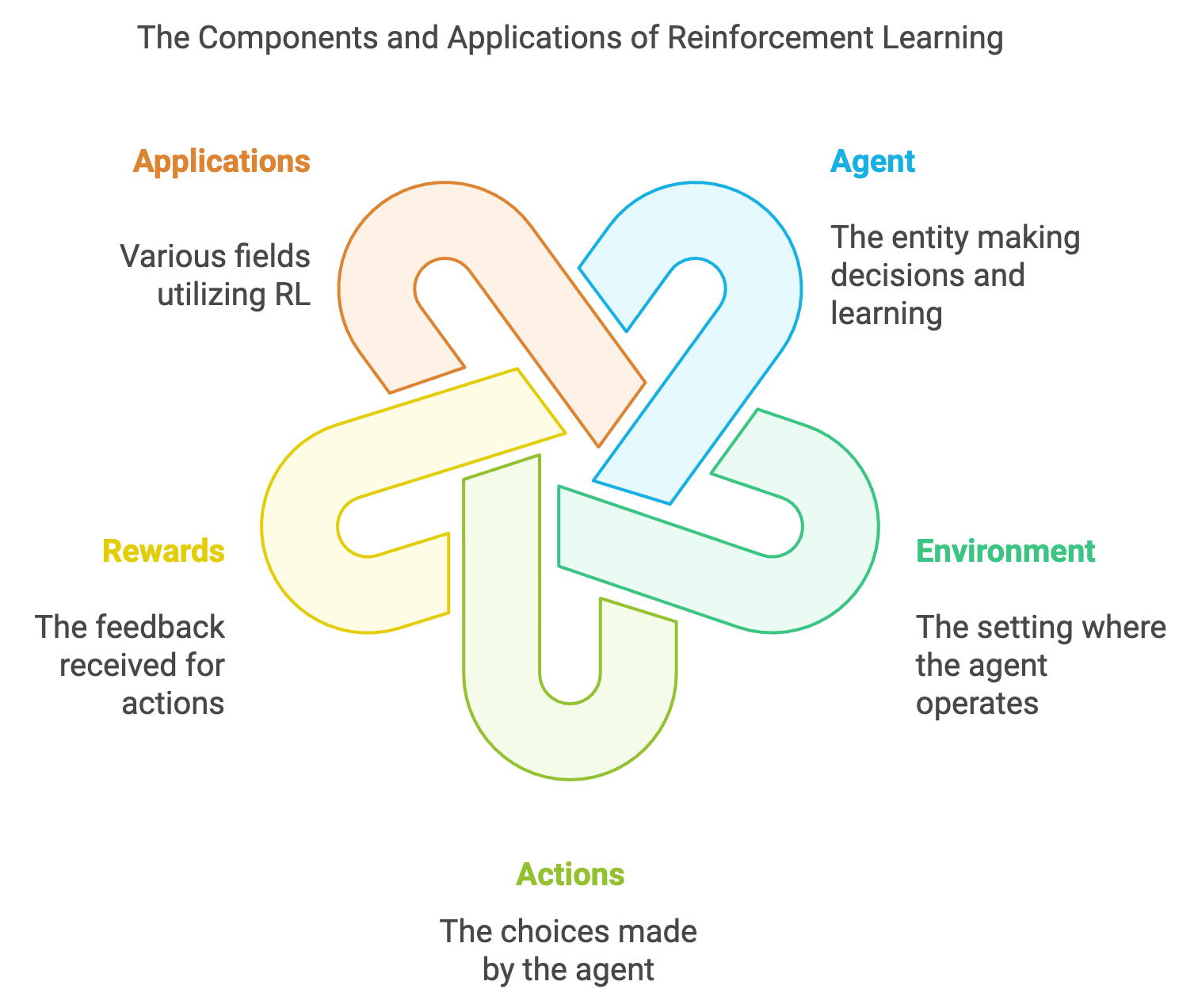

Chapter 1 of RLVR provides a comprehensive introduction to the foundational and modern approaches to reinforcement learning (RL) through the powerful framework of Rust. The chapter begins with a deep dive into the core concepts of RL, drawing from Richard Sutton's seminal work, to establish a solid understanding of agents, environments, states, actions, rewards, and policies. It contrasts RL with supervised and unsupervised learning, and introduces key RL algorithms like Q-learning, SARSA, and policy gradients. Readers will explore the fundamental challenges in RL, such as the exploration vs. exploitation dilemma and the mathematical underpinnings of Markov Decision Processes (MDP). The chapter also covers practical implementation strategies using Rust, including setting up a basic RL agent and experimenting with different learning parameters in a simple environment. Moving forward, the chapter delves into modern RL techniques such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Actor-Critic methods, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), emphasizing the role of deep learning in enhancing RL capabilities. The chapter provides hands-on examples of implementing these algorithms using Rust crates like tch-rs and ndarray, showcasing how to handle complex environments and continuous action spaces. Finally, the chapter addresses the practicalities of implementing RL algorithms in Rust, offering insights into best practices for project structuring, performance optimization, and the integration of essential tools for monitoring and debugging RL experiments. Through this chapter, readers will gain a robust foundation in RL, understand the modern advancements in the field, and learn how to effectively implement and optimize RL algorithms using Rust.

1.1. Fundamentals of Reinforcement Learning (RL)

Imagine teaching a dog to fetch a ball. You don’t hand it a step-by-step manual or label its every move. Instead, you throw the ball, observe its actions, and reward it with a treat when it successfully brings the ball back. Over time, the dog learns which actions lead to positive outcomes. This process, driven by trial and error and guided by feedback, captures the essence of Reinforcement Learning (RL). RL is a paradigm in machine learning designed to teach an agent how to make sequential decisions based on scientific principles to maximize rewards. By interacting with its environment, learning from the consequences of its actions, and refining its strategy, an agent trained with RL can optimize long-term outcomes, much like the dog learning to fetch the ball.

Figure 1: RL agent trained to make sequential actions in environment to maximize rewards.

At its core, RL trains agents to solve problems in dynamic environments where outcomes are uncertain and depend on a series of interdependent actions. Unlike supervised learning, where labeled data guides the learning process, or unsupervised learning, which identifies patterns in data without explicit labels, RL operates in a realm of exploration and discovery. The agent learns through experimentation, exploring possibilities, and receiving feedback in the form of rewards or penalties. This makes RL particularly suited for solving sequential decision-making problems, where the agent must weigh immediate actions against their long-term impact.

The foundation of RL lies in the reward hypothesis, which posits that all goals can be described as the maximization of cumulative rewards. This simple yet powerful principle enables RL to model diverse real-world scenarios, from robotics to finance, healthcare, and gaming. The mathematical rigor of RL is rooted in decision theory, where the agent's goal is to optimize a cumulative reward function that captures the trade-off between immediate and future benefits. By navigating this balance, RL enables agents to learn policies—strategies mapping states to actions—that lead to optimal performance over time.

The importance of RL becomes evident when we consider its wide-ranging applications. In robotics, RL teaches machines to walk, manipulate objects, or navigate obstacles, adapting to changing environments with remarkable flexibility. In finance, RL helps optimize trading strategies by learning to balance risk and reward across multiple transactions. In healthcare, RL assists in treatment planning, weighing short-term effects against long-term patient outcomes. In gaming, RL powers AI systems that master complex games like Go and StarCraft, demonstrating strategic thinking and adaptability that often surpass human expertise. These examples showcase RL’s ability to handle environments where decisions must account for delayed consequences and evolving conditions.

Reinforcement Learning’s significance extends even further in the field of artificial intelligence with its role in training current Large Language Models (LLMs). Modern LLMs like GPT are fine-tuned using Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), a variant of RL that incorporates human preferences into the reward system. Specifically, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), an advanced RL algorithm, is employed during this process to refine the model's responses. PPO is a policy gradient method that balances exploration and exploitation, optimizing the language model’s performance while maintaining stability and computational efficiency. Through this approach, LLMs learn to align their outputs with human expectations, enhancing usability and ensuring ethical AI behavior.

The use of RLHF and PPO in training cutting-edge AI systems highlights the growing importance of RL. Mastering RL concepts is no longer confined to niche domains like robotics or gaming; it has become integral to the development of AI systems that interact seamlessly with humans. Understanding RL provides insight into how these models are designed, optimized, and aligned with real-world objectives. Moreover, it equips learners with the tools to innovate in areas where sequential decision-making, feedback optimization, and ethical considerations are critical.

To better understand RL intuitively, consider running a business. The environment represents the market, the state reflects the business's current condition (such as inventory levels or cash flow), and actions are the decisions made, like launching a new product or adjusting prices. Rewards are the profits or losses resulting from these actions. The business’s goal is not merely short-term success but long-term sustainability, much like the agent in RL. RL mathematically captures this idea through the discounted cumulative reward, which balances immediate results with future gains, guiding the agent to prioritize actions that maximize overall outcomes.

RL can also be likened to playing a video game. The agent is the player, the environment is the game world, and rewards are the points scored for achieving objectives. As the player explores the game, they try different strategies, learn from failures, and refine their approach with each attempt. The policy they develop is akin to a player’s evolving strategy to win the game. This feedback-driven learning process is central to RL’s power, enabling agents to operate effectively in uncertain and dynamic environments.

The distinguishing feature of RL is its framework for learning by doing. The agent starts with little to no knowledge of the environment, explores various strategies, learns from feedback, and iteratively improves its performance. Through this process, the agent balances exploration—trying new actions to gather information—and exploitation—using its existing knowledge to achieve the best-known outcomes. This balance is crucial for RL's success, allowing agents to adapt and optimize their behavior over time.

Reinforcement Learning is a convergence of scientific principles, mathematical rigor, and practical adaptability. It combines the flexibility of biological learning with the precision of machine intelligence, enabling systems to think, learn, and act intelligently in dynamic, uncertain environments. By teaching agents to make sequential, scientifically guided decisions, RL transforms abstract goals into actionable intelligence, pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence in industries ranging from robotics and healthcare to finance and entertainment. With its critical role in training the world’s most advanced AI models, RL is not just a cornerstone of intelligent decision-making—it is a key to unlocking the future of machine learning.

The story of Reinforcement Learning (RL) begins at the intersection of neuroscience, psychology, and mathematics. Its roots trace back to the early 20th century, when psychologists like Edward Thorndike and B.F. Skinner developed theories of behaviorism, emphasizing learning through rewards and punishments. Thorndike’s Law of Effect posited that actions followed by positive outcomes are likely to be repeated, laying the groundwork for RL’s central idea: maximizing cumulative reward. Skinner extended these concepts with his experiments on operant conditioning, demonstrating how feedback could shape behavior over time. These early insights from psychology would later inspire the formalization of RL in the realm of artificial intelligence.

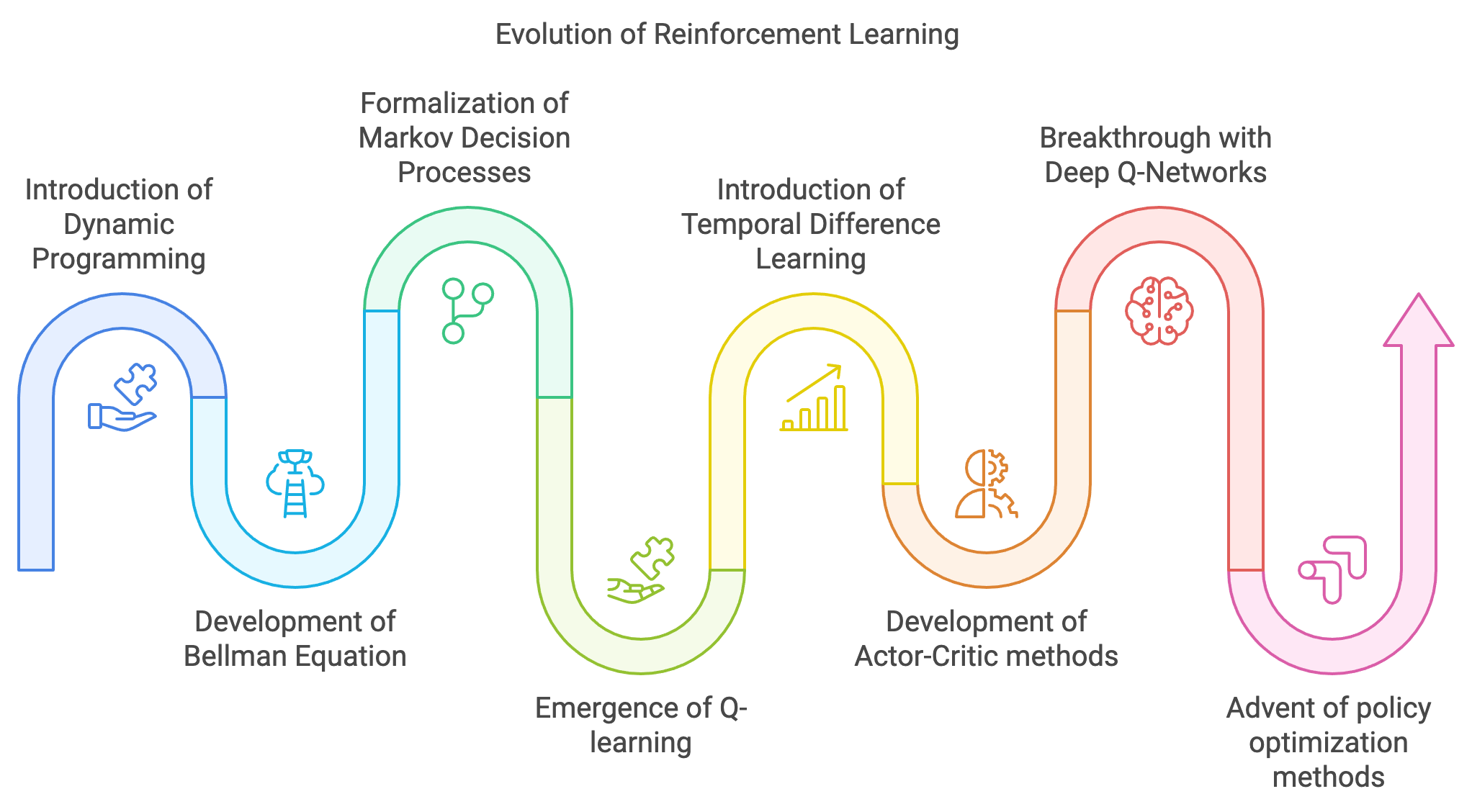

In the mid-20th century, mathematicians and computer scientists began translating these behavioral theories into computational models. Richard Bellman’s work in the 1950s introduced Dynamic Programming, providing a mathematical framework for solving sequential decision-making problems. Bellman’s Bellman Equation, which expresses the value of a state as the maximum expected cumulative reward achievable from that state onward, became a cornerstone of RL. Around the same time, the development of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) by Andrey Markov and later formalized in decision theory, offered a way to model environments where future states depend only on the current state and action, not on the sequence of past events. These foundational contributions connected decision-making with mathematical rigor, setting the stage for RL as a computational discipline.

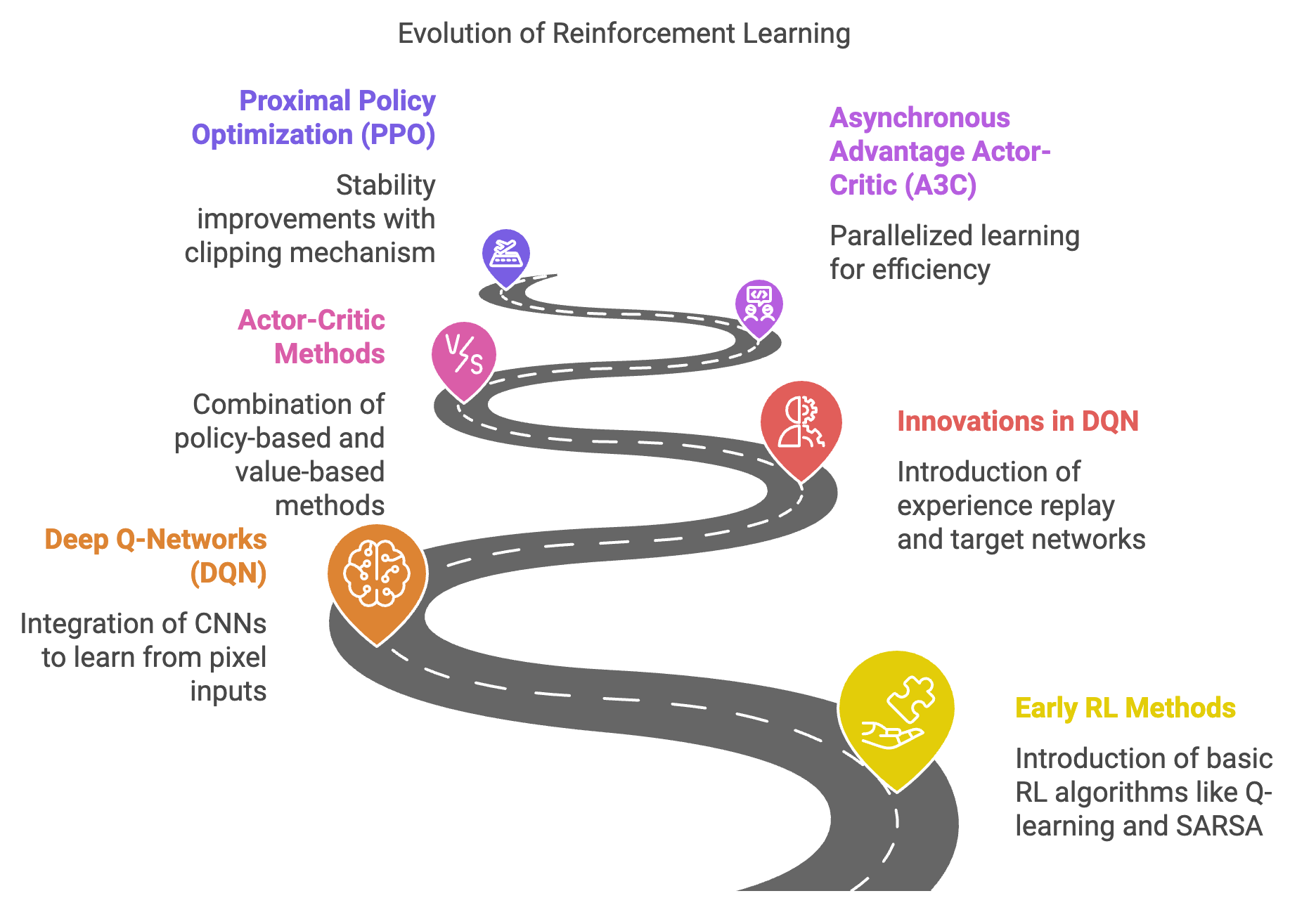

Figure 2: The evolution of Reinforcement Learning models.

The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a surge of interest in machine learning, with RL emerging as a distinct area of study. Researchers like Chris Watkins developed algorithms such as Q-learning, an off-policy method for learning action-value functions without requiring a model of the environment. Q-learning’s simplicity and effectiveness in finding optimal policies made it a seminal algorithm in RL. At the same time, Temporal Difference (TD) Learning, pioneered by Richard Sutton, introduced a method for updating value functions incrementally, blending ideas from Monte Carlo methods and Dynamic Programming. These innovations marked a shift from purely theoretical exploration to practical algorithm development, enabling RL to tackle increasingly complex problems.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw RL gain traction in artificial intelligence, robotics, and control systems. The development of Actor-Critic methods, combining policy-based (actor) and value-based (critic) approaches, represented a significant advancement in RL’s ability to learn policies for high-dimensional and continuous action spaces. These methods laid the groundwork for modern policy gradient techniques, which would later become central to RL’s success in real-world applications.

The turn of the millennium marked a new phase in RL’s evolution, fueled by advances in computational power and growing interest in artificial intelligence. Algorithms like SARSA (State-Action-Reward-State-Action) and Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) began to bridge the gap between traditional RL and modern machine learning. DQNs, developed by DeepMind in 2013, were a breakthrough in combining RL with deep learning. By using deep neural networks to approximate Q-values, DQNs enabled agents to learn directly from raw pixel inputs in high-dimensional state spaces. This innovation, demonstrated through the agent’s ability to achieve superhuman performance in Atari games, reignited interest in RL and demonstrated its potential for complex, real-world tasks.

The next transformative leap in RL came with the advent of policy optimization methods like Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). These methods refined policy gradient techniques, offering greater stability and efficiency in training. PPO, in particular, emerged as a gold standard for modern RL applications due to its balance between exploration and exploitation. It became a core component of reinforcement learning frameworks, enabling robust performance across diverse tasks. Around the same time, AlphaGo, developed by DeepMind, leveraged RL and deep learning to defeat human champions in the ancient game of Go, a feat previously thought to be decades away. AlphaGo’s success showcased RL’s ability to master strategic decision-making in environments with vast state-action spaces.

In the late 2010s, RL began to merge with advances in generative modeling, paving the way for its role in modern Generative AI. The introduction of Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) marked a pivotal moment, enabling the fine-tuning of large-scale language models like GPT. RLHF integrates human preferences into the reward function, ensuring that models align their outputs with human expectations. For instance, GPT models are trained initially through supervised learning and then fine-tuned using RLHF, with algorithms like PPO optimizing the policy to improve performance and ensure safe, ethical outputs. This combination of RL and human feedback has become critical in creating AI systems that are both powerful and aligned with human values.

Today, RL stands at the forefront of artificial intelligence, driving breakthroughs in robotics, autonomous systems, gaming, and natural language processing. Its journey from psychological theories to computational models, and finally to the training of modern generative AI, reflects its profound versatility and transformative potential. As we enter an era defined by AI’s integration into every facet of society, understanding RL’s historical evolution offers valuable insights into how intelligent systems learn, adapt, and optimize their behavior. The ongoing advancements in RL not only promise to refine AI systems further but also underscore the importance of exploring and mastering this dynamic field.

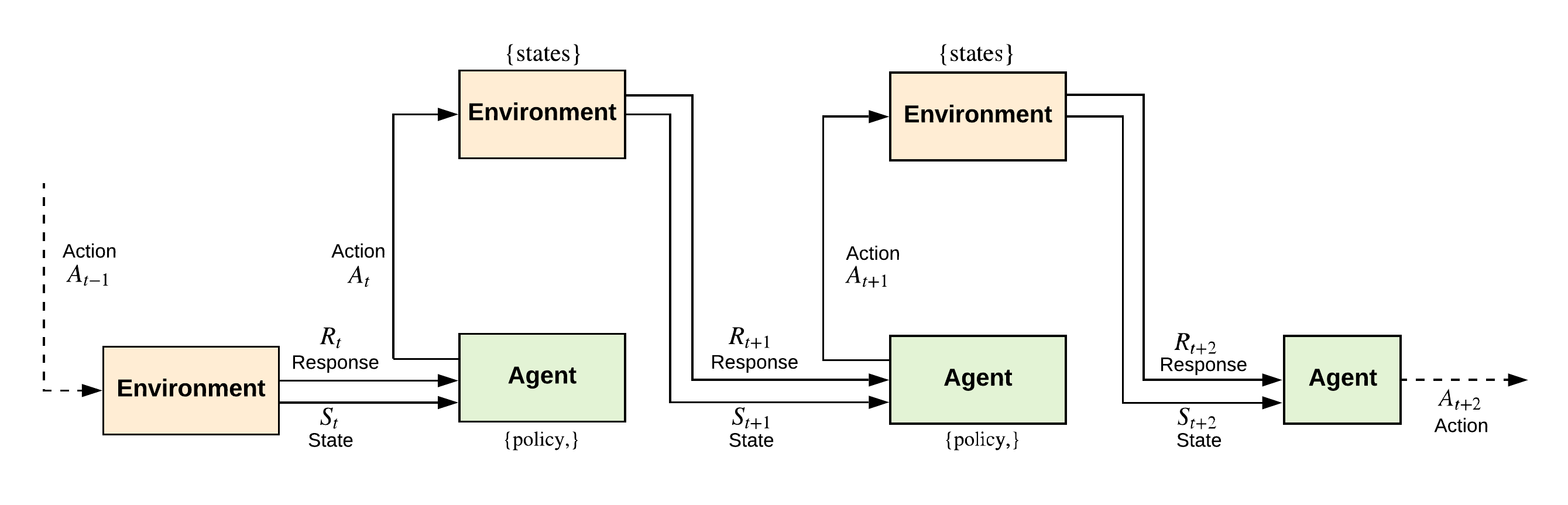

Figure 3: A recursive representation of the Agent-Environment interface in RL model.

Reinforcement Learning is more than just an algorithm; it is a framework for intelligent decision-making. By enabling agents to learn through interaction and optimize their actions for long-term outcomes, RL represents a fundamental step toward creating systems that can think, adapt, and perform in the real world. Its applications span industries and domains, offering solutions to problems that demand flexibility, learning, and continuous improvement. As we explore RL further, its foundational concepts and practical implementations will reveal how this paradigm transforms abstract learning into actionable intelligence. At its core, RL involves an agent and an environment. The agent is the learner or decision-maker, while the environment represents the external system with which the agent interacts. This interaction is formalized through the following components:

State ($S$): The current situation or observation of the environment.

Action ($A$): A decision taken by the agent that affects the environment.

Reward/Response ($R$): Scalar feedback from the environment to evaluate the quality of an action.

Policy ($\pi$): A strategy mapping states to actions.

Value Function ($V(s)$): The expected cumulative reward from a given state under a policy.

The RL process unfolds as a sequence of steps where the agent observes a state $s_t \in S$, takes an action $a_t \in A$, transitions to a new state $s_{t+1}$, and receives a reward $r_t$. The goal is to discover a policy $\pi^*$ that maximizes the expected return:

$$ G_t = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=0}^\infty \gamma^k R(s_{t+k}, a_{t+k}) \right], $$

where $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor prioritizing immediate rewards over distant ones.

The equation for the expected return $G_t$ captures the essence of decision-making in Reinforcement Learning (RL). This expression formalizes the agent's objective: to maximize the cumulative reward over time. The summation $\sum_{k=0}^\infty$ aggregates the rewards received at each time step $t+k$, weighted by the factor $\gamma^k$, which ensures that rewards received in the future are given less importance compared to immediate rewards. This diminishing weight is critical because, in many real-world scenarios, immediate feedback is more reliable and actionable than distant outcomes. The expectation $\mathbb{E}$ reflects the probabilistic nature of the environment, accounting for the uncertainty in state transitions and outcomes due to the agent’s actions.

The discount factor $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is a crucial parameter that governs the trade-off between short-term and long-term rewards. When $\gamma$ is close to 1, the agent becomes farsighted, valuing future rewards almost as much as immediate ones. This is suitable for tasks where long-term planning is essential, such as financial investments or strategic gameplay. Conversely, when $\gamma$ is closer to 0, the agent is myopic, focusing primarily on immediate rewards, which is ideal for environments with high uncertainty or where immediate gains are critical. The inclusion of $\gamma$ ensures the mathematical convergence of the infinite sum, as each successive term $\gamma^k R(s_{t+k}, a_{t+k})$ diminishes exponentially, making the expected return well-defined even for infinite horizons. This balance between present and future, controlled by $\gamma$, is a cornerstone of RL’s ability to model intelligent, goal-driven behavior in complex environments.

To appreciate the distinctiveness of Reinforcement Learning (RL), it is helpful to compare it to other major machine learning paradigms: supervised learning and unsupervised learning. Each paradigm represents a unique approach to solving problems based on the nature of the data and the feedback provided during the learning process.

In supervised learning, the process is analogous to a teacher grading a student's work. The model is trained on a dataset containing labeled input-output pairs, where the labels represent the correct answers. For instance, if the task is image classification, each image is paired with its corresponding label (e.g., "dog" or "cat"). The model’s goal is to minimize the error between its predictions and the correct answers, guided by immediate feedback after every prediction. This setup ensures a structured learning process where the model progressively improves its accuracy by learning from explicit corrections.

Unsupervised learning, on the other hand, is more exploratory. It is like a student organizing their study notes into meaningful categories without any guidance on how those categories should look. In this paradigm, the data lacks explicit labels, and the model must identify patterns or groupings within the dataset. For example, clustering algorithms like k-means partition data into distinct groups based on similarities. Here, the emphasis is on uncovering hidden structures within the data rather than making specific predictions.

Reinforcement Learning diverges significantly from these approaches by focusing on sequential decision-making through trial and error. It is akin to a child learning to play chess, where the only feedback comes at the end of the game, signaling whether they won or lost. The agent interacts with an environment, takes actions, and receives rewards or penalties based on the outcomes of those actions. Unlike supervised learning, where feedback is immediate and explicit, RL requires the agent to infer the value of its actions by observing their cumulative effects over time. This delayed feedback makes RL particularly suited for problems where actions have long-term consequences, such as optimizing strategies in complex games, managing supply chains, or controlling robotic systems.Exploration vs. Exploitation Dilemma

An essential aspect of RL is the trade-off between exploration (trying new actions to gather information) and exploitation (leveraging known actions to maximize rewards). The $\epsilon$-greedy strategy addresses this dilemma by choosing a random action with probability $\epsilon$ (exploration) and the best-known action with probability $1 - \epsilon$ (exploitation). Mathematically:

$$ a = \begin{cases} \text{random action} & \text{with probability } \epsilon, \\ \arg \max_a Q(s, a) & \text{with probability } 1 - \epsilon. \end{cases} $$

The Markov property ensures that the future depends only on the current state and action, not on the sequence of past states:

$$ P(s_{t+1} | s_t, a_t, s_{t-1}, a_{t-1}, \dots) = P(s_{t+1} | s_t, a_t). $$

MDPs provide a mathematical framework for RL, where optimality is defined by the Bellman equations:

Value Function:$V^\pi(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma V^\pi(s') \right].$

Action-Value Function: $.Q^\pi(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma Q^\pi(s', \pi(s')) \right].$

The Markov property is fundamental to defining Reinforcement Learning (RL) because it ensures that decision-making processes are both computationally tractable and theoretically robust. By stating that the future state depends only on the current state and action, not on the history of prior states, the Markov property simplifies the modeling of dynamic environments into a Markov Decision Process (MDP). This reduction enables the use of recursive formulations like the Bellman equation, which underpins key RL algorithms. Without the Markov assumption, the agent would need to consider an exponentially growing sequence of past states and actions to make decisions, leading to intractable computations. The property aligns with the principle of sufficient statistics, where the current state encapsulates all necessary information about the environment's history relevant to future outcomes. This abstraction is particularly critical for RL, where the goal is to learn optimal policies efficiently in stochastic and dynamic settings. Moreover, the Markov property facilitates rigorous probabilistic reasoning, allowing the agent to leverage transition probabilities $P(s'|s, a)$ and reward distributions $R(s, a)$ to predict and maximize long-term rewards. While the assumption may not perfectly hold in all real-world applications, designing state representations that approximate the Markov property often makes RL feasible, providing a balance between simplicity and the complexity of real-world decision-making.

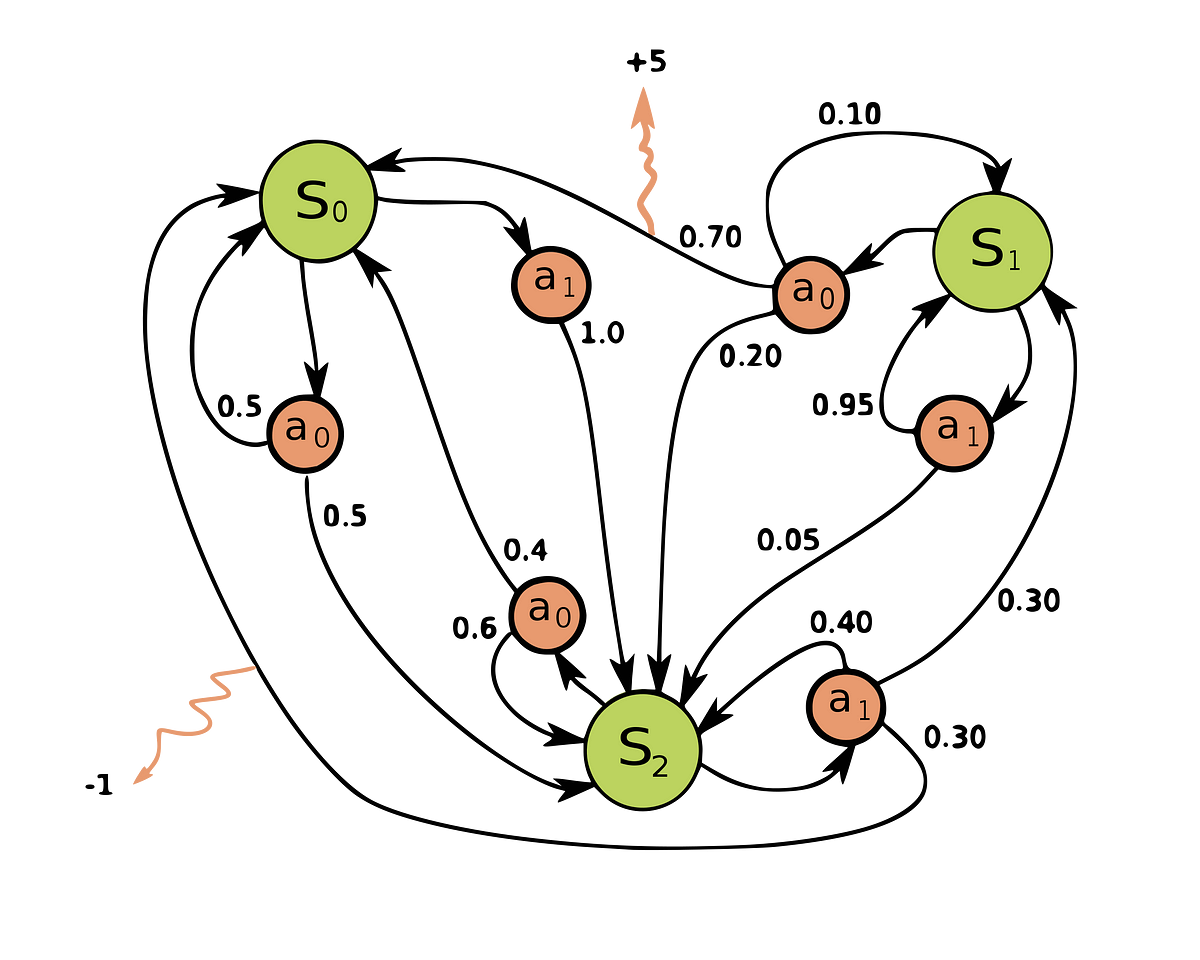

Imagine the mechanic of an MDP as a mathematical framework for modeling decision-making in environments with uncertainty. In this MDP, the agent transitions between states ($S_0, S_1, S_2$) by taking actions ($a_0, a_1$), which result in probabilistic state transitions. Each transition is associated with a reward (depicted by $r$) that evaluates the desirability of the outcome. The transitions and rewards are governed by probabilities, represented as $P(s'|s, a)$, which indicate the likelihood of reaching a new state $s'$ from state $s$ after taking action $a$. The goal of the agent is to learn an optimal policy, which maps states to actions to maximize the cumulative reward over time while navigating this dynamic environment. The diagram highlights the essence of the Markov property, which asserts that the future state depends only on the current state and action, not on the sequence of past states. It is important to note that, under the Markov property, the future is conditionally independent of the past, given the present.

Figure 4: A visual representation of an MDP showing states, actions, transitions, and rewards in a probabilistic environment.

The design of the reward function profoundly influences agent behavior. For instance, a poorly designed reward can lead to unintended consequences, such as the agent exploiting the system to achieve high rewards in ways that do not align with the task objectives.

The power of RL lies in its algorithmic diversity, which addresses various types of decision-making problems. Some key algorithms, for example, that form the backbone of RL include Q-learning, SARSA, and policy gradient methods. Each represents a distinct approach to balancing exploration, exploitation, and learning in dynamic environments. Imagine you are navigating through a forest to find treasure. Q-learning is like using a pre-built map where you estimate the best paths (actions) to take from any point (state), even if you occasionally wander off the map to explore; it learns the optimal path by prioritizing the maximum potential reward at every decision point, regardless of your current approach. SARSA, on the other hand, is like creating your own map as you explore, sticking closely to the specific paths you’ve actually taken and refining them based on your current strategy; it updates its knowledge cautiously, considering the actions you truly commit to. Meanwhile, policy gradient methods are like relying on intuition and a compass rather than a map, directly optimizing your sense of direction (policy) to find the best overall strategy, particularly useful when paths are complex or involve smooth, continuous decisions like climbing a mountain rather than choosing discrete steps. Each method offers a unique way to learn and improve, depending on how structured or flexible the environment and goals are.

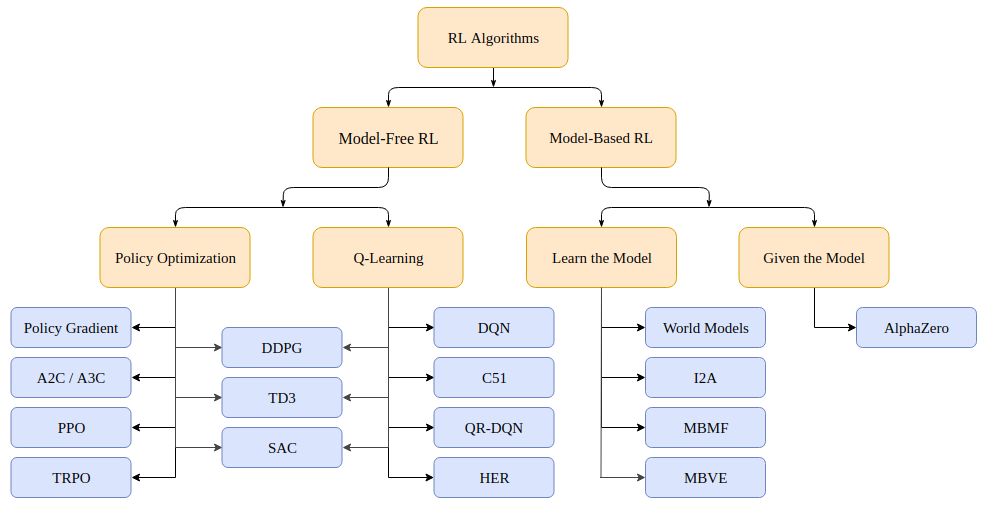

Figure 5: Taxonomy of RL algorithms.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms are broadly categorized into Model-Free and Model-Based approaches, with each category offering unique methodologies for training agents to interact with and learn from their environments. This taxonomy highlights the depth and versatility of RL, which has evolved over time to include various subcategories and hybrid techniques.

Model-Free RL methods focus on direct learning from interaction without constructing an explicit model of the environment’s dynamics. These methods are particularly well-suited for scenarios where the environment is either unknown or too complex to model. Model-free algorithms are divided into value-based and policy optimization approaches, with some hybrid methods blending the two. Value-based methods aim to estimate functions like $Q(s, a)$, which represent the expected cumulative reward for taking action aaa in state sss, and then derive optimal policies from these estimates. Q-learning, a foundational off-policy method, updates the action-value function using the rule:

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left[ R + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right]. $$

Here, $\alpha$ represents the learning rate, $R$ the immediate reward, and $\gamma$ the discount factor, while $\max_{a'} Q(s', a')$ captures the maximum future value. Extensions of Q-learning, such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN), approximate $Q(s, a)$ using neural networks, enabling RL to scale to high-dimensional environments like video games. Another value-based approach, SARSA (State-Action-Reward-State-Action), updates $Q(s, a)$ based on the action actually taken under the current policy, as expressed by

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left[ R + \gamma Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right]. $$

This on-policy nature makes SARSA more conservative and effective in stochastic or safety-critical settings.

Policy optimization methods, in contrast, directly optimize the policy $\pi(a|s)$, a parameterized distribution over actions given states, to maximize the expected return. The optimization typically uses the policy gradient theorem, where the gradient of the expected return $J(\pi_\theta)$ is expressed as

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a|s) G_t \right]. $$

Advanced algorithms like Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) refine this approach by introducing constraints or clipping mechanisms, ensuring stable updates and preventing overcorrections in the policy. Hybrid methods such as Actor-Critic combine value estimation and policy optimization, with the actor updating the policy and the critic evaluating it through a value function.

Model-Based RL differs fundamentally by incorporating a model of the environment, either given or learned, into the decision-making process. When the model is known, algorithms like Value Iteration and Policy Iteration compute optimal policies by solving the Bellman equation iteratively, where the value of a state is defined as

$$ V(s) = \max_a \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s'|s, a)V(s') \right]. $$

Such methods, rooted in dynamic programming, are computationally efficient for small state-action spaces but struggle to scale to high-dimensional problems. In contrast, when the model must be learned, the agent uses interaction data to approximate the transition dynamics and reward functions. This enables model-based planning, where simulated trajectories are used to evaluate and improve policies. Algorithms like Dyna-Q blend model-based and model-free techniques by using a learned model to generate synthetic experiences for value function updates.

Recent advancements have introduced novel extensions and hybrid approaches to address specific challenges in RL. Hierarchical RL decomposes tasks into subgoals, enabling agents to tackle complex problems with structured learning. Multi-Agent RL (MARL) handles environments with multiple interacting agents, fostering advancements in cooperative and competitive settings. Safe RL integrates constraints to ensure policies adhere to safety requirements, critical for real-world applications like robotics and healthcare. Offline RL, or Batch RL, learns from static datasets without requiring active interaction, making it highly applicable in scenarios where exploration is costly or risky. Meta-RL explores the ability of agents to generalize across tasks by learning how to learn, improving adaptability in diverse environments.

This taxonomy reflects the evolution of RL, from early methods like Q-learning to advanced approaches integrating model-based planning and policy optimization. These techniques have proven invaluable across domains, from robotics and autonomous systems to the training of large-scale generative models like GPT, where methods such as Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) combine policy optimization with human-aligned rewards. The breadth of RL’s methodologies ensures its adaptability to an ever-expanding range of real-world challenges.

Several core concepts underpin Reinforcement Learning (RL), shaping its mathematical foundations and practical implementations. These concepts include the exploration vs. exploitation dilemma, the Markov Decision Process (MDP), and the reward signal, each of which is integral to understanding how RL systems learn and optimize behavior.

The exploration vs. exploitation dilemma is one of the most critical challenges in RL, representing the trade-off between trying new actions (exploration) and leveraging known successful actions (exploitation). Imagine a chef experimenting with recipes. Exploration involves trying unconventional ingredients to discover innovative flavors, while exploitation means sticking to tried-and-true dishes that are already popular. In RL, an agent must balance these conflicting objectives to achieve optimal long-term performance. If it explores too much, it risks spending excessive time on suboptimal actions; if it exploits too early, it might miss out on potentially better strategies. Strategies like the $\epsilon$-greedy method capture this balance. With a small probability $\epsilon$, the agent selects random actions (exploration), while with $1 - \epsilon$, it chooses the best-known action (exploitation). Over time, $\epsilon$ often decays, allowing the agent to shift from exploration toward exploitation as it gains confidence in its knowledge of the environment. This dynamic adjustment ensures that the agent can navigate environments where the optimal strategies are initially unknown.

The Markov Decision Process (MDP) formalizes the RL environment and provides the mathematical scaffolding for decision-making. The MDP assumes the Markov property, where the future state depends only on the current state and action, not the sequence of preceding states. This property is akin to driving with GPS: the current location and decision (e.g., turn left or right) determine the next location, without needing a record of every road traveled to date. The Markov property simplifies learning by reducing the amount of information the agent needs to consider, making problems computationally feasible. The Bellman equation embodies this principle, recursively defining the value of a state $V(s)$ as the immediate reward $R(s, a)$ plus the discounted value of future states:

$$ V(s) = \max_a \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s'|s, a) V(s') \right]. $$

This famous equation allows RL algorithms to systematically evaluate and improve policies by breaking complex, long-term decision-making into manageable steps. The discount factor $\gamma$ ensures that rewards received sooner are prioritized over distant ones, reflecting real-world scenarios where immediate benefits often outweigh uncertain future gains.

The Bellman equation intuitively captures the essence of decision-making in the context of a Markov Decision Process (MDP) by breaking down the value of a state into two components: the immediate reward and the future rewards expected from subsequent states. Imagine you are navigating a maze to reach a treasure. The value of your current position is not just the gold coins you might find now (the immediate reward), but also the promise of the treasure you can eventually reach by taking the best path from here. This future reward depends on the actions you take, the states you transition to, and the probabilities of those transitions. The Bellman equation formalizes this idea by expressing the value of a state $V(s)$ as the sum of the immediate reward $R(s, a)$ for taking an action aaa, and the discounted value of future states $\gamma V(s')$, weighted by the transition probability $P(s'|s, a)$. It provides a recursive relationship, allowing RL algorithms to compute optimal policies iteratively by propagating the value of future rewards back to earlier decisions, ensuring a balance between short-term and long-term gains.

The reward signal is the compass guiding the agent’s behavior, providing feedback that motivates actions leading to desirable outcomes. Well-designed rewards encourage the agent to adopt behaviors that align with the intended goals, much like a teacher rewarding students for completing assignments correctly. However, crafting an effective reward function is challenging and requires careful thought. For instance, a robot vacuum cleaner rewarded solely for covering the largest area might inefficiently clean the same spots repeatedly instead of focusing on genuinely dirty regions. Such misaligned incentives highlight the risk of "reward hacking," where the agent exploits loopholes in the reward function rather than achieving the intended objectives. Designing rewards that align with desired outcomes—while avoiding unintended consequences—is essential for ensuring RL's success in real-world applications. For instance, in autonomous driving, rewards might balance multiple factors like minimizing travel time, ensuring passenger comfort, and obeying traffic rules.

Together, these important concepts—balancing exploration and exploitation, leveraging the Markov property for computational efficiency, and designing effective reward signals—form the backbone of RL. They highlight the intricate interplay of theory, experimentation, and application that makes RL a powerful framework for creating intelligent systems capable of learning and adapting in dynamic environments.

Through these algorithms and concepts, RL provides a framework for intelligent decision-making, enabling agents to learn, adapt, and optimize their behavior in complex, dynamic environments. By bridging theory and practice, RL continues to shape the future of artificial intelligence, driving innovation across industries and domains.

To start your practical journey, let’s implement an RL agent in a stochastic gridworld environment using Rust. This example includes advanced concepts like stochastic transitions, dynamic exploration rates, and cumulative reward calculation.

use ndarray::{Array2};

use rand::Rng;

const GRID_SIZE: usize = 5;

const NUM_ACTIONS: usize = 4; // Actions: Up, Down, Left, Right

const ALPHA: f64 = 0.1; // Learning rate

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.9; // Discount factor

const INITIAL_EPSILON: f64 = 0.9;

const EPSILON_DECAY: f64 = 0.995;

const MIN_EPSILON: f64 = 0.1;

const EPISODES: usize = 500;

fn main() {

let mut q_table = Array2::<f64>::zeros((GRID_SIZE * GRID_SIZE, NUM_ACTIONS));

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut epsilon = INITIAL_EPSILON;

for _episode in 0..EPISODES {

let mut state = rng.gen_range(0..GRID_SIZE * GRID_SIZE);

let mut done = false;

while !done {

// Epsilon-greedy action selection

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..NUM_ACTIONS) // Explore

} else {

q_table.row(state)

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap_or(0) // Exploit

};

let (next_state, reward, terminal) = step(state, action);

done = terminal;

// Q-learning update

let max_q_next = q_table.row(next_state).iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

q_table[[state, action]] += ALPHA * (reward + GAMMA * max_q_next - q_table[[state, action]]);

state = next_state;

}

// Decay epsilon

epsilon = (epsilon * EPSILON_DECAY).max(MIN_EPSILON);

}

println!("Trained Q-table:\n{}", q_table);

}

fn step(state: usize, action: usize) -> (usize, f64, bool) {

let x = state % GRID_SIZE;

let y = state / GRID_SIZE;

let (next_x, next_y) = match action {

0 => (x, y.saturating_sub(1)), // Up

1 => (x, (y + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1)), // Down

2 => (x.saturating_sub(1), y), // Left

3 => ((x + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1), y), // Right

_ => (x, y),

};

let next_state = next_x + next_y * GRID_SIZE;

let reward = if next_state == GRID_SIZE * GRID_SIZE - 1 { 10.0 } else { -0.1 };

let terminal = next_state == GRID_SIZE * GRID_SIZE - 1;

(next_state, reward, terminal)

}

This Rust code implements a basic Q-learning algorithm to train an agent navigating a gridworld environment. The grid has a size of $5 \times 5$, with each cell representing a state, and the agent can take one of four possible actions: moving up, down, left, or right. The agent learns an optimal policy by updating a Q-table, which stores the action-value pairs for every state. Initially, the Q-table is filled with zeros, and the agent explores the environment using an epsilon-greedy strategy. The $\epsilon$-greedy approach enables the agent to explore actions randomly with a probability $\epsilon$ and exploit the best-known actions with a probability $1 - \epsilon$. Over 500 episodes, the agent repeatedly interacts with the environment, updates its Q-values using the Bellman equation, and decays $\epsilon$ to gradually shift from exploration to exploitation as it learns.

The step function simulates the environment dynamics, calculating the next state based on the agent's current state and action. If the agent reaches the goal state (the last cell in the grid), it receives a reward of 10.0 and terminates the episode. Otherwise, it receives a small penalty of -0.1 to encourage efficient exploration. After each action, the Q-value for the state-action pair is updated using the formula:

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left[ R + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right], $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, $R$ is the reward, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $\max_{a'} Q(s', a')$ represents the maximum Q-value of the next state. This update ensures that the Q-values progressively converge to the optimal action-values as the agent learns from its experiences. The final Q-table, printed at the end, contains the learned values that the agent can use to make optimal decisions in the gridworld.

This simple implementation demonstrates advanced insights into reinforcement learning by incorporating dynamic exploration decay and stochastic transitions, which together create a robust RL system. The exploration rate ($\epsilon$) decreases over time, gradually shifting the agent’s focus from exploration to exploitation as it learns, ensuring an efficient balance between discovering new strategies and refining known ones. The environment also includes stochastic transitions, where the agent's actions influence state changes under realistic constraints, mimicking the uncertainty of real-world conditions. These elements work together to enable the agent to learn optimal policies in uncertain and dynamic environments, establishing a strong foundation for exploring more advanced RL algorithms and real-world applications.

1.2. Modern Approaches in Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has undergone a dramatic transformation over the last two decades, evolving from simple methods confined to small, discrete problems into a powerful framework capable of solving highly complex, real-world challenges. Early methods like tabular Q-learning and SARSA laid the groundwork for RL, offering algorithms that iteratively updated a value table to learn the optimal behavior. However, these approaches were like teaching a chess player by memorizing specific board positions and moves; they worked well in small, finite spaces but faltered when faced with large or continuous environments. The integration of neural networks into RL—a paradigm now known as Deep Reinforcement Learning (Deep RL)—revolutionized the field. Neural networks enabled RL algorithms to approximate complex functions, such as value functions $Q(s, a)$ or policies $\pi(a|s)$, allowing agents to extract meaningful representations from raw, high-dimensional inputs like images, just as humans interpret visual scenes while playing games or driving cars.

Figure 6: The evolution of RL models from early methods to modern PPO.

This transformative journey began with Deep Q-Networks (DQN), a pivotal breakthrough in Deep RL. DQN extended traditional Q-learning by using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to approximate the action-value function $Q(s, a)$, enabling agents to learn directly from pixel inputs. Imagine playing a video game like Space Invaders: instead of explicitly coding rules for every possible situation, the agent watches the game screen, learns which actions (e.g., moving left or right) lead to higher scores, and updates its strategy accordingly. Mathematically, DQN computes the Q-value $Q(s, a)$ update iteratively as the current estimate of the action-value and $\max_{a'} Q(s', a')$ is the maximum estimated value of the next state $s'$. DQN introduced two critical innovations—experience replay and target networks—to stabilize training. Experience replay is like studying past games by randomly sampling memories (state-action-reward transitions) to break correlations and ensure better generalization. Target networks act as a slower-updating reference, preventing oscillations in learning, much like a coach who provides consistent feedback instead of constantly changing their advice.

The evolution of RL didn’t stop with DQN. Actor-Critic methods emerged as a powerful hybrid approach, combining the strengths of policy-based and value-based methods. The actor directly maps states to actions by optimizing the policy $\pi(a|s)$, while the critic evaluates the actor’s actions by estimating the value function $V(s)$ or the advantage function $A(s, a)$. Mathematically, the policy gradient in Actor-Critic is expressed as $\nabla_\theta J(\pi_\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a|s) A(s, a) \right],$ where $A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s)$ represents the advantage of an action $a$ in state $s$. An analogy here would be a team of climbers ascending a mountain: the actor decides the direction to climb based on intuition (the policy), while the critic analyzes the terrain and provides feedback on whether the direction leads closer to the peak (value estimation). Methods like A3C (Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic) parallelized this process, enabling agents to learn more efficiently by leveraging multiple instances of the environment simultaneously.

The next leap came with Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which addressed the stability challenges of earlier policy-based methods like Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO). PPO simplifies policy updates by introducing a clipping mechanism that prevents the policy from changing too drastically in a single update. The PPO objective is $L(\theta) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \min \left( r_t(\theta) A_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A_t \right) \right],$ where $r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(a_t|s_t)}$ is the probability ratio between the new and old policies, and $A_t$ is the advantage estimate. Clipping ensures that the ratio $r_t(\theta)$ stays within a controlled range, balancing exploration and exploitation. PPO’s efficiency and robustness have made it the de facto standard for continuous action spaces, enabling advancements in robotics (e.g., teaching robots to manipulate objects) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) in training large language models like GPT. For instance, GPT fine-tuning uses PPO to align model outputs with human preferences, creating coherent and human-like responses in natural language tasks.

Finally, model-based RL has seen a resurgence with advancements in latent space modeling. Early model-based approaches were criticized for inaccuracies in learned models, but modern methods like Dreamer address this by learning compact representations of the environment and planning in this latent space. This is akin to mentally simulating moves in a chess game without physically playing, allowing for efficient learning in environments where real-world interactions are expensive. By combining planning, prediction, and policy learning, model-based RL has opened new frontiers in decision-making for complex, resource-constrained scenarios like autonomous driving or logistics optimization.

In summary, the evolution of RL reflects a journey from simple table-based algorithms to sophisticated, deep learning-powered methods capable of solving high-dimensional, continuous, and partially observable problems. Through innovations like DQN, Actor-Critic, PPO, and model-based approaches, RL has transformed from a theoretical framework into a practical tool shaping industries as diverse as gaming, robotics, healthcare, and artificial intelligence. This transformative journey showcases the interplay of mathematics, computation, and human ingenuity, making RL one of the most exciting frontiers in machine learning.

The tch-rs crate is a powerful and efficient Rust wrapper for PyTorch, making it an excellent tool for implementing deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithms. With its seamless integration of tensor operations and support for GPU acceleration, tch-rs enables developers to build and train neural networks in Rust for computationally demanding tasks like Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Actor-Critic methods, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). In this DQN implementation, tch-rs is used to define neural network architectures, such as multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models, which are essential for approximating complex value functions in high-dimensional or sequential environments. The crate also supports robust backpropagation through the nn module, which includes various optimizers like Adam, and efficient tensor manipulation for batching experiences from a replay buffer. By leveraging tch-rs, the implementation integrates experience replay and target networks, which are crucial for stabilizing training and mitigating issues like non-stationarity in deep RL. This framework not only demonstrates the practical application of advanced DRL techniques but also highlights the power of Rust for developing high-performance machine learning systems.

use tch::{nn, Tensor, Device};

use rand::{Rng, thread_rng};

use std::collections::VecDeque;

const BUFFER_CAPACITY: usize = 10000; // Replay buffer capacity

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64; // Mini-batch size

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.001; // Learning rate

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99; // Discount factor

const TARGET_UPDATE_FREQ: usize = 10; // Frequency to update target network

// Define the Q-network

fn build_q_network(vs: &nn::Path, input_dim: i64, output_dim: i64) -> nn::Sequential {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer1", input_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer2", 128, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "output", 128, output_dim, Default::default()))

}

// Define the Experience Replay Buffer

struct ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque<(Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool)>,

}

impl ReplayBuffer {

fn new() -> Self {

ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque::with_capacity(BUFFER_CAPACITY),

}

}

fn push(&mut self, experience: (Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool)) {

if self.buffer.len() == BUFFER_CAPACITY {

self.buffer.pop_front(); // Remove oldest experience

}

self.buffer.push_back(experience);

}

fn sample(&self) -> Vec<(Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool)> {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let indices: Vec<usize> = (0..self.buffer.len())

.choose_multiple(&mut rng, BATCH_SIZE);

indices.into_iter()

.map(|idx| self.buffer[idx].clone())

.collect()

}

}

// Main Training Loop

fn train_dqn() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let target_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let input_dim = 4; // Example: CartPole state space dimensions

let output_dim = 2; // Example: CartPole action space dimensions

let q_network = build_q_network(&vs.root(), input_dim, output_dim);

let target_network = build_q_network(&target_vs.root(), input_dim, output_dim);

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE).unwrap();

let mut replay_buffer = ReplayBuffer::new();

for episode in 0..500 {

let mut state = Tensor::randn(&[1, input_dim], (tch::Kind::Float, device));

let mut done = false;

while !done {

// Epsilon-greedy action selection

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate (decays over time in practice)

let action = if rand::random::<f64>() < epsilon {

rand::random::<i64>() % output_dim // Explore

} else {

q_network.forward(&state).argmax(1, true).int64_value(&[0]) // Exploit

};

// Simulate environment step (placeholder)

let next_state = Tensor::randn(&[1, input_dim], (tch::Kind::Float, device));

let reward = 1.0; // Example reward

let terminal = rand::random::<bool>(); // Example terminal condition

replay_buffer.push((state.copy(), action, reward, next_state.copy(), terminal));

if replay_buffer.buffer.len() >= BATCH_SIZE {

// Sample mini-batch

let batch = replay_buffer.sample();

let states: Tensor = Tensor::stack(&batch.iter().map(|b| b.0.copy()).collect::<Vec<_>>(), 0);

let actions: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&batch.iter().map(|b| b.1).collect::<Vec<_>>());

let rewards: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&batch.iter().map(|b| b.2).collect::<Vec<_>>());

let next_states: Tensor = Tensor::stack(&batch.iter().map(|b| b.3.copy()).collect::<Vec<_>>(), 0);

let terminals: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&batch.iter().map(|b| b.4 as i32).collect::<Vec<_>>());

// Compute Q-value targets

let next_q_values = target_network.forward(&next_states).max_dim(1, true).0;

let targets = rewards + GAMMA * next_q_values * (1.0 - terminals.to_kind(tch::Kind::Float));

// Compute loss and backpropagate

let q_values = q_network.forward(&states).gather(1, &actions.unsqueeze(-1), false);

let loss = (q_values - targets.unsqueeze(-1)).pow(2).mean();

optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

}

state = next_state;

done = terminal;

}

// Update target network periodically

if episode % TARGET_UPDATE_FREQ == 0 {

target_network.copy(&vs);

}

}

}

The goal of this implementation is to train an RL agent to solve tasks like CartPole by estimating the optimal Q-values for state-action pairs. The architecture consists of two neural networks: the primary Q-network and a target network. The Q-network learns the action-value function $Q(s, a)$ that predicts the cumulative reward for taking an action $a$ in state $s$. The target network serves as a stable reference for the Q-value updates, preventing oscillations and divergence during training. These updates are performed using the Bellman equation, where the loss function minimizes the difference between predicted Q-values and the expected rewards based on the target network.

The experience replay buffer is central to this implementation, enabling efficient learning by storing and reusing past experiences $(s, a, r, s', \text{done})$. The buffer randomly samples mini-batches of transitions, breaking temporal correlations and ensuring stable training. During each training episode, the agent selects actions using an $\epsilon$-greedy strategy, which balances exploration (random actions) and exploitation (greedy actions based on the Q-network). The agent transitions to a new state, receives a reward, and records the experience in the replay buffer. Periodically, the model samples a mini-batch to compute Q-value targets using the target network, updates the Q-network parameters through backpropagation, and synchronizes the target network with the primary network. This architecture and training loop demonstrate key innovations in DQN, such as experience replay, target networks, and batch training, ensuring efficient and stable learning in high-dimensional environments.

In subsequent chapters of RLVR, we will implement more methods, such as Actor-Critic and PPO frameworks, leveraging similar structures to solve more complex, real-world RL tasks. By building these implementations in Rust, we demonstrate the power and versatility of modern RL techniques in high-performance environments.

1.3. Implementing RL Algorithms in Rust

Reinforcement Learning (RL) in Rust is uniquely empowered by a growing ecosystem of specialized libraries that address diverse aspects of RL workflows. Rust’s focus on safety, performance, and concurrency makes it particularly well-suited for implementing RL algorithms that require high computational efficiency and scalability. Key libraries such as candle, tch-rs, ndarray, gym-rs, rustsim, and rayon provide the foundation for building robust RL systems. These libraries collectively enable developers to construct neural networks, optimize RL algorithms, design and simulate environments, and implement parallel training pipelines. This ecosystem is especially valuable in modern RL applications, including the training and fine-tuning of large language models (LLMs) with reinforcement learning components, such as Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF).

The candle and tch-rs libraries are central to Rust's RL ecosystem, offering extensive support for deep learning. Candle is a lightweight and flexible framework ideal for prototyping and experimentation, enabling users to build and train neural networks efficiently. Its minimalistic design makes it especially appealing for researchers focusing on RL algorithm innovation or for integrating RL into computationally constrained applications. On the other hand, tch-rs, a Rust binding for PyTorch, is better suited for large-scale RL tasks due to its GPU acceleration, advanced tensor operations, and seamless interoperability with PyTorch-trained models. This capability is critical for RL applications in LLMs, where neural networks must handle massive parameter spaces and optimize policies for high-dimensional, dynamic environments. These libraries allow RL practitioners to implement algorithms like Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), and Actor-Critic methods, bridging the gap between RL and deep learning.

Complementing these deep learning frameworks, libraries like ndarray, gym-rs, and rustsim extend Rust’s RL capabilities into environment design and algorithm implementation. Ndarray excels in managing tabular data and mathematical operations, making it indispensable for classical RL algorithms like Q-learning and SARSA. Gym-rs provides seamless access to popular RL benchmark environments, such as CartPole and LunarLander, through Rust-native bindings to OpenAI Gym, facilitating experimentation and testing of RL models. For tasks requiring custom environments or physics-based simulations, rustsim offers tools to model realistic dynamics and interactions, enabling advanced use cases like robotic manipulation and autonomous vehicle control. Finally, rayon, a powerful concurrency library, enhances the scalability of RL training by enabling parallel environment rollouts or multi-agent simulations, significantly reducing training time. Together, these libraries provide a comprehensive toolkit for building scalable, high-performance RL systems, from foundational algorithms to cutting-edge applications in artificial intelligence.

1.2.1. Ndarray Crate

The ndarray is a powerful Rust library for numerical computations, offering efficient handling of multi-dimensional arrays. It provides robust capabilities for matrix manipulations, making it particularly well-suited for implementing simpler reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms like Q-learning and SARSA. In low-dimensional and discrete state-action spaces, where neural networks may be unnecessary, ndarray becomes an indispensable tool. Its ability to efficiently represent and update Q-tables, combined with its simplicity and high performance, makes it an ideal choice for tabular RL methods.

Reinforcement learning often starts with foundational algorithms like tabular Q-learning, where the state-action values are stored in a table rather than approximated by a neural network. The Q-table, essentially a 2D matrix mapping states to actions, is updated iteratively using the Bellman equation. Ndarray excels at representing and manipulating such tabular data, enabling the efficient computation of updates for all state-action pairs.

The following example demonstrates how to implement Q-learning using ndarray to manage the Q-table. This implementation models a discrete environment with 10 states and 4 possible actions per state.

use ndarray::Array2;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

// Initialize the Q-table with zeros (10 states, 4 actions)

let mut q_table = Array2::<f64>::zeros((10, 4));

let gamma = 0.9; // Discount factor

let alpha = 0.1; // Learning rate

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Run 1000 episodes of training

for _episode in 0..1000 {

let mut state = rng.gen_range(0..10); // Start from a random initial state

for _step in 0..100 {

// Select an action using an epsilon-greedy strategy

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore: random action

} else {

q_table.row(state).iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap() // Exploit: greedy action

};

// Simulate environment step (random next state and reward for simplicity)

let next_state = rng.gen_range(0..10);

let reward = rng.gen_range(-1.0..1.0);

let done = rng.gen_bool(0.1); // Termination condition

// Update the Q-value using the Bellman equation

let max_q_next = q_table.row(next_state).iter().cloned().fold(f64::MIN, f64::max);

q_table[[state, action]] += alpha * (reward + gamma * max_q_next - q_table[[state, action]]);

// Transition to the next state

state = next_state;

if done {

break;

}

}

}

// Print the trained Q-table

println!("Trained Q-table:\n{}", q_table);

}

In this implementation, the Q-table is represented as a 2D array (Array2) with dimensions corresponding to the number of states and actions. Each episode begins in a random initial state, and the agent interacts with the environment for up to 100 steps per episode. The action selection is governed by an ϵ\\epsilonϵ-greedy strategy, where the agent balances exploration (selecting random actions) and exploitation (choosing the best-known actions based on the Q-table). After each step, the Q-value for the selected state-action pair is updated based on the reward received and the maximum Q-value of the next state.

The Bellman update formula is implemented efficiently using ndarray’s ability to access and modify matrix elements. The row method retrieves the Q-values for a specific state, and iter is used to find the maximum Q-value for the next state, which is essential for computing the temporal difference error. These operations highlight ndarray’s strength in handling matrix computations, making it ideal for tabular RL.

While the example above demonstrates the use of ndarray for basic Q-learning, the library’s flexibility makes it an excellent tool for extending tabular reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms to incorporate more advanced concepts. For instance, eligibility traces, a critical component in algorithms like SARSA(λ) and Q(λ), can be efficiently implemented by maintaining an additional 2D array to track these traces for every state-action pair. Eligibility traces accelerate learning by crediting states and actions that contributed to recently experienced rewards, effectively blending aspects of Monte Carlo and temporal-difference methods. With ndarray, developers can use matrix operations to update both the Q-table and the trace matrix simultaneously, streamlining the implementation of more sophisticated temporal-difference learning.

In tabular policy gradient methods, policies can be explicitly represented as probability distributions over actions for each state. This involves using a 2D array where each row corresponds to a state and each column represents the probability of selecting a particular action. These policies are updated iteratively using gradient-based methods to maximize expected cumulative rewards. By leveraging ndarray for such probabilistic representations, developers can efficiently implement and refine tabular policy gradient algorithms, including the computation of gradients and updates across all states. The library’s ability to handle complex matrix operations simplifies this process, making it suitable for tasks that require direct manipulation of tabular policies.

Furthermore, ndarray can be applied in multi-agent RL scenarios, where multiple Q-tables or policies must be maintained to model cooperative or competitive interactions between agents. For example, in a cooperative multi-agent environment, each agent could maintain its own Q-table, while in competitive settings, shared policies or strategies might be updated based on individual or global rewards. Using ndarray, developers can construct and manipulate these multi-dimensional structures with ease, facilitating the extension of single-agent tabular RL techniques to multi-agent systems. By providing a robust, efficient foundation for matrix manipulation, ndarray empowers developers to explore advanced RL techniques while ensuring computational efficiency and maintainability. Its combination of simplicity and power makes it an invaluable tool for advancing tabular RL methods in both research and practical applications.

1.2.2. Hugging Face’s Candle Crate

Candle is a lightweight and high-performance deep learning framework designed in Rust, offering simplicity and efficiency for developers aiming to integrate neural networks into reinforcement learning (RL) workflows. Its design prioritizes modularity and computational efficiency, making it well-suited for tasks requiring streamlined architectures, such as implementing policies or value functions in RL. Candle's lightweight nature ensures that it is highly resource-efficient, an essential feature for training and deploying RL agents in environments with constrained computational resources, such as embedded systems or edge devices. Its Rust-native design provides the additional benefit of memory safety and concurrency, ensuring robust performance for large-scale or high-speed RL applications.

Candle simplifies the process of constructing and training neural networks, providing an intuitive API that supports both standard and complex architectures. For RL implementations, this ease of use allows developers to focus on algorithmic innovation rather than framework complexities. For instance, constructing a Q-network— a fundamental component in Deep Q-Networks (DQN) — is straightforward in Candle. Such networks approximate the Q-value function, which predicts the expected cumulative reward for a given state-action pair. Candle also integrates seamlessly with RL algorithms like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) or Actor-Critic methods, where neural networks are used to approximate policies or advantage functions. Its lightweight yet expressive design makes it a compelling choice for prototyping advanced RL workflows, including those that involve Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) for fine-tuning large language models (LLMs).

The following code demonstrates how to construct a Q-network in Candle. This network takes a state vector as input, processes it through two fully connected layers with ReLU activations, and outputs Q-values for each possible action. The simplicity of Candle's API ensures that the network can be easily integrated into larger RL pipelines, such as DQN or policy gradient methods.

use candle::{Tensor, Device, Result};

use candle_nn::{linear, Module};

struct QNetwork {

layer1: linear::Linear,

layer2: linear::Linear,

output: linear::Linear,

}

impl QNetwork {

fn new(input_dim: usize, hidden_dim: usize, output_dim: usize, device: &Device) -> Result<Self> {

Ok(Self {

layer1: linear(input_dim, hidden_dim, device)?,

layer2: linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim, device)?,

output: linear(hidden_dim, output_dim, device)?,

})

}

fn forward(&self, input: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

let x = input.apply(&self.layer1)?.relu();

let x = x.apply(&self.layer2)?.relu();

x.apply(&self.output)

}

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let device = Device::Cpu;

let q_network = QNetwork::new(4, 128, 2, &device)?;

let state = Tensor::new(&[1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0], (4,), &device)?;

let q_values = q_network.forward(&state)?;

println!("Q-values: {:?}", q_values);

Ok(())

}

In this implementation, the Q-network is constructed with two hidden layers, each followed by a ReLU activation to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to model complex state-action relationships. The input vector represents the state of the environment, while the output vector corresponds to the Q-values for each action. This structure is versatile and can be adapted to RL tasks like Deep Q-Learning, where the Q-values guide the agent's action selection.

To integrate this Q-network into a training loop, one could use it to predict Q-values for a given state and then update the network's weights based on the Bellman equation. For example, in DQN, the network learns by minimizing the temporal difference error between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value computed from the environment's reward and the next state's Q-values. Candle provides the necessary tools to implement this process efficiently, including support for gradient-based optimization and tensor operations. A training loop using a replay buffer for stability could look like the following:

fn train(q_network: &mut QNetwork, replay_buffer: &ReplayBuffer, device: &Device) -> Result<()> {

for (state, action, reward, next_state, done) in replay_buffer.sample_batch() {

let current_q = q_network.forward(&state)?.gather(1, &action.unsqueeze(0))?;

let max_next_q = q_network.forward(&next_state)?.max_dim(1, false).0;

let target_q = reward + (1.0 - done as f64) * 0.99 * max_next_q; // γ = 0.99

let loss = (current_q - target_q).pow(2).mean()?;

q_network.optimizer.step(loss)?;

}

Ok(())

}

Here, the network is trained by sampling transitions from a replay buffer, computing the target Q-value using the Bellman equation, and updating the network parameters to minimize the error between the predicted and target Q-values. The replay buffer helps break correlations in the data, ensuring stable and efficient learning.

Candle’s efficiency and flexibility extend beyond Q-learning to other RL paradigms like policy optimization or Actor-Critic methods. For example, one could extend the Q-network to a policy network that outputs probabilities for each action, enabling the use of algorithms like PPO or A3C. Its lightweight design ensures that researchers and practitioners can experiment with RL algorithms in resource-constrained environments or develop Rust-native solutions for production systems. By combining performance, simplicity, and extensibility, Candle is a powerful tool for integrating deep learning into RL workflows.

1.2.3. Tch-rs Crate

The tch-rs is a Rust binding for PyTorch, designed to bring the power of PyTorch’s deep learning capabilities to the Rust ecosystem. It enables developers to construct, train, and deploy neural networks in Rust with access to GPU acceleration and advanced tensor operations. Tch-rs is particularly well-suited for reinforcement learning (RL) tasks that require large-scale computations, such as training agents in high-dimensional state and action spaces or optimizing policies in continuous environments. Its seamless compatibility with PyTorch models allows developers to leverage pre-trained networks and advanced architectures, bridging the gap between the research-oriented Python ecosystem and the performance-driven Rust ecosystem.

The primary advantage of tch-rs in RL is its ability to handle computationally intensive tasks, such as deep reinforcement learning (Deep RL), with ease. For instance, Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Actor-Critic methods, and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) rely heavily on neural networks to approximate value functions, policies, or both. With tch-rs, these networks can be implemented and trained efficiently using highly optimized matrix operations and GPU acceleration. Moreover, tch-rs supports dynamic computation graphs, making it flexible for experimenting with different RL algorithms and architectures. This flexibility is critical in tasks like Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), where large-scale neural networks, such as those used in large language models (LLMs), are fine-tuned using reinforcement learning techniques.

The following implementation demonstrates how to construct a policy network in tch-rs for RL tasks. This network takes a state vector as input, processes it through multiple hidden layers, and outputs a probability distribution over actions. Such a network is a foundational component in policy-based RL algorithms like PPO, where the policy is optimized to maximize expected cumulative rewards.

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor, Device};

struct PolicyNetwork {

model: nn::Sequential,

optimizer: nn::Optimizer<nn::Adam>,

}

impl PolicyNetwork {

// Initialize the policy network with input, hidden, and output dimensions

fn new(input_dim: i64, hidden_dim: i64, output_dim: i64, device: Device) -> Self {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let model = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "layer1", input_dim, hidden_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "layer2", hidden_dim, hidden_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "output", hidden_dim, output_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.softmax(1, tch::Kind::Float)); // Softmax to output probabilities

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

PolicyNetwork { model, optimizer }

}

// Forward pass through the network

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.model.forward(state)

}

// Perform a gradient step to update network parameters

fn optimize(&mut self, loss: Tensor) {

self.optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

}

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available(); // Use GPU if available

let mut policy = PolicyNetwork::new(4, 128, 2, device);

// Example state tensor

let state = Tensor::randn(&[1, 4], (tch::Kind::Float, device));

let action_probs = policy.forward(&state);

println!("Action probabilities: {:?}", action_probs);

}

In this example, the policy network is defined as a sequence of linear layers interspersed with ReLU activations, followed by a softmax layer to produce a probability distribution over actions. This structure is versatile and can be extended for more complex architectures, such as convolutional networks for image-based environments or recurrent networks for sequential decision-making tasks.

To integrate the policy network into an RL algorithm like PPO, one would compute the loss based on the policy gradient and update the network parameters using the optimizer. The following code outlines a simplified training loop for PPO, highlighting the use of tch-rs for tensor operations and optimization:

fn train_ppo(policy: &mut PolicyNetwork, states: &Tensor, actions: &Tensor, advantages: &Tensor, old_log_probs: &Tensor) {

let log_probs = policy.forward(states).gather(1, &actions.unsqueeze(-1), false).squeeze();

let ratios = (log_probs - old_log_probs).exp();

let clipped_ratios = ratios.clamp(1.0 - 0.2, 1.0 + 0.2); // PPO clipping range

let loss = -advantages * clipped_ratios.min(ratios);

let loss = loss.mean(tch::Kind::Float);

policy.optimize(loss);

}

Here, the policy network computes the log probabilities of actions taken during training. The PPO objective function optimizes the policy by maximizing the advantage-weighted probability ratio while applying a clipping mechanism to ensure stability. Tch-rs handles the tensor operations efficiently, even for large batches of data, making it well-suited for modern RL algorithms.

The tch-rs also excels in scenarios where high-dimensional environments or continuous action spaces are involved. For example, in robotics, where an agent needs to control multiple joints simultaneously, policies often output continuous values rather than discrete probabilities. Tch-rs can accommodate this requirement by supporting architectures that output mean and variance parameters for Gaussian policies, enabling the use of algorithms like Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) or Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG).

In conclusion, tch-rs combines the computational power of PyTorch with the safety and performance of Rust, making it a powerful framework for RL development. Its ability to handle dynamic computation graphs, GPU acceleration, and advanced neural network architectures makes it indispensable for implementing state-of-the-art RL algorithms. Whether you are prototyping RL models or building production-ready systems, tch-rs provides the tools to efficiently implement and scale your workflows, especially when integrated with other Rust-native libraries for environment simulation or parallel processing. This makes it a cornerstone of reinforcement learning in Rust, particularly for applications that demand high performance and scalability, such as training agents in complex, real-world environments.

1.2.4. Environment Simulation Crates

In reinforcement learning (RL), environments play a pivotal role, providing the dynamic settings where agents learn, interact, and evolve. The gym-rs library offers a robust and advanced framework for creating and managing RL environments within the Rust ecosystem. By serving as a native binding to OpenAI Gym, gym-rs provides Rust developers with direct access to a diverse array of standardized RL tasks, enabling seamless integration into high-performance Rust-based workflows.

The gym-rs is particularly powerful due to its ability to bridge the capabilities of Rust with the standardized environments of OpenAI Gym, such as CartPole, LunarLander, and MountainCar. These benchmark tasks are foundational in RL research, serving as critical testbeds for algorithm development and validation. Gym-rs elevates these environments by enabling their use within Rust’s memory-safe, concurrent, and highly performant architecture. This allows researchers and developers to push the boundaries of RL experimentation while benefiting from Rust’s inherent strengths in computational efficiency and safety.

Consider an advanced use case with gym-rs that demonstrates its capability to integrate reinforcement learning algorithms into Rust workflows. In the following example, a Q-learning agent is trained on the CartPole environment. The implementation incorporates state discretization, enabling the agent to map continuous observations into finite state spaces. This approach showcases how Gym-rs can be combined with sophisticated RL techniques while leveraging Rust’s performance advantages.

use gym::{GymClient, SpaceData};

use ndarray::{Array2};

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

// Create a Gym client and initialize the CartPole environment

let client = GymClient::default();