Chapter 3

Bandit Algorithms and Exploration-Exploitation Dilemmas

"In reinforcement learning, the exploration-exploitation dilemma is at the heart of decision-making, and mastering it opens the door to truly intelligent systems." — Richard Sutton

Chapter 3 of RLVR delves into the fundamental and practical aspects of bandit algorithms, a crucial component of reinforcement learning that addresses the exploration-exploitation dilemma. The chapter begins with an introduction to the multi-armed bandit problem, where the goal is to maximize cumulative rewards while balancing the trade-off between exploring new actions and exploiting known successful ones. This section lays the groundwork by explaining key metrics like regret and the importance of minimizing it to improve decision-making over time. The chapter then explores greedy and epsilon-greedy algorithms, detailing their mechanisms, strengths, and limitations, while providing practical Rust implementations to observe how different exploration strategies impact long-term performance. Following this, the chapter introduces more sophisticated algorithms such as Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling, both of which offer robust solutions to the exploration-exploitation trade-off through probabilistic and confidence-bound approaches. Practical exercises in Rust demonstrate the implementation of these algorithms and their effectiveness in minimizing regret. The chapter concludes with a discussion on contextual bandits, an advanced extension of the bandit problem where decisions are informed by additional contextual information. By implementing and experimenting with contextual bandits in Rust, readers will gain a deeper understanding of how context can enhance decision-making and improve outcomes in various applications, from personalized recommendations to adaptive clinical trials. Through this chapter, readers will not only grasp the theoretical foundations of bandit algorithms but also acquire hands-on experience in applying these concepts using Rust.

3.1. Introduction to Bandit Problems

The multi-armed bandit problem is a cornerstone of decision theory and reinforcement learning (RL), offering a mathematically elegant framework for understanding the trade-offs inherent in sequential decision-making under uncertainty. It captures the fundamental tension between exploration, which involves gathering information about the environment, and exploitation, which leverages existing knowledge to maximize rewards. The problem is named after the analogy of a gambler facing $K$ slot machines ("bandits"), each with an unknown reward distribution. The gambler's goal is to determine, over repeated plays, which machines to play to maximize cumulative rewards.

Figure 1: Illustration of MAB - Multi Arm Bandit Problem.

This simplified yet powerful abstraction has numerous real-world applications. For example, in online advertising, a platform must decide which ad to display to a user (the "arm") to maximize click-through rates. Similarly, in clinical trials, researchers aim to allocate treatments to patients to identify the most effective therapy while minimizing harm or wasted resources. By formalizing this dilemma, the bandit problem provides a foundation for developing efficient algorithms that balance learning and reward optimization.

The multi-armed bandit problem is a classic challenge in reinforcement learning (RL), offering a simplified yet powerful framework to study decision-making under uncertainty. Imagine a gambler faced with $K$ slot machines (arms), each with an unknown probability of payout. The gambler must decide which machine to play at each time step, aiming to maximize their cumulative reward over a fixed number of plays. Mathematically, this problem is formalized by associating each arm $k$ with a reward distribution $R_k$. At each time step $t$, the agent selects an arm $A_t \in \{1, 2, \dots, K\}$ and receives a stochastic reward $R_t \sim R_{A_t}$.

The objective is to maximize the total reward:

$$ G_T = \sum_{t=1}^T R_t, $$

over a horizon of $T$ time steps. However, since the reward distributions are unknown, the agent must navigate the tension between exploration (gathering more information about the arms) and exploitation (choosing the arm with the highest observed reward). This tension lies at the heart of bandit problems and is a critical concept in RL.

In bandit problems, the performance of a strategy (policy) $\pi$ is often evaluated using the concept of regret. Regret quantifies the difference between the cumulative reward of an optimal strategy and the cumulative reward obtained by the chosen strategy:

$$ R_T = \sum_{t=1}^T \mu^* - \sum_{t=1}^T \mathbb{E}[R_t], $$

where $\mu^* = \max_k \mu_k$ is the expected reward of the optimal arm, and $\mu_k$ is the expected reward of arm $k$. Regret effectively measures the cost of not always selecting the optimal arm. The goal of bandit algorithms is to minimize regret, ensuring that the strategy learns to approximate the optimal choice over time.

The exploration vs. exploitation dilemma is a central challenge in bandit problems. Exploitation involves selecting the arm that appears most rewarding based on current knowledge, while exploration involves choosing an arm with less certainty to potentially discover better rewards. Mathematically, exploitation corresponds to selecting the arm:

$$A_t = \arg\max_k \hat{\mu}_k,$$

where $\hat{\mu}_k$ is the estimated mean reward of arm $k$. Exploration, on the other hand, requires introducing randomness into the decision-making process to ensure all arms are sufficiently sampled. Balancing these two goals is crucial, as excessive exploration wastes opportunities to exploit known rewards, while insufficient exploration may prevent the discovery of better arms.

Consider the analogy of trying to find the best coffee shop in a new city. Exploration involves trying out different cafes, even those that seem less promising, to uncover hidden gems or better alternatives. This phase is driven by curiosity and the need to gather information. Exploitation, on the other hand, means sticking to the coffee shop you already know and enjoy, prioritizing immediate satisfaction. While exploitation can be comforting and rewarding in the short term, over-reliance on it might cause you to miss out on discovering a new favorite that surpasses your current choice.

Algorithms like Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) emulate this decision-making process by strategically balancing exploration and exploitation. They quantify uncertainty through confidence intervals, prioritizing exploration of options with less information early on. This helps ensure sufficient data is gathered about each choice's potential rewards. Over time, as more information is collected, the algorithm shifts towards exploiting the options that consistently yield high rewards, optimizing cumulative gains. This dynamic strategy mirrors the process of efficiently navigating uncertainty, making well-informed decisions that maximize overall satisfaction, whether in discovering coffee shops or solving complex real-world problems.

Bandit problems are inherently stochastic, as the rewards for each arm are drawn from unknown distributions. This randomness necessitates probabilistic decision-making. For instance, the observed reward $R_t$ at each time step is only a noisy approximation of the true mean reward $\mu_k$. Effective bandit algorithms must incorporate this stochasticity into their strategies to make robust decisions under uncertainty.

The basic bandit problem provides a foundational framework for decision-making under uncertainty, but real-world scenarios often demand more sophisticated adaptations. These variants and extensions expand the bandit problem to accommodate complex environments and dynamic behaviors.

In contextual bandits, the agent is presented with additional information or "context" at each time step. For example, in an online advertising scenario, the context could include user demographics or browsing history. The reward distribution of each arm (e.g., the likelihood of a user clicking on an ad) depends on this context. The challenge is to learn a policy that maps contexts to arms to maximize cumulative rewards, requiring algorithms to balance learning both the context-arm relationships and the inherent exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Adversarial bandits introduce an element of unpredictability, where rewards are not drawn from fixed distributions but instead are determined by an adversary. This setup reflects competitive environments, such as financial markets or cybersecurity, where an opponent may strategically influence outcomes. Algorithms like EXP3 (Exponential-weight algorithm for Exploration and Exploitation) are designed to handle these challenges by assigning exponential weights to actions based on observed performance, ensuring resilience in non-stationary or adversarial conditions.

In non-stationary bandits, reward distributions change over time, reflecting environments with evolving dynamics. For example, the popularity of a product may fluctuate with trends, requiring algorithms to adapt by discounting older observations or resetting knowledge periodically. Techniques like sliding windows or decay factors help maintain relevance in such fluid scenarios, ensuring the agent stays effective as the environment shifts.

Combinatorial bandits address situations where the decision involves selecting combinations of arms, such as allocating resources across multiple tasks or choosing a portfolio of investments. The action space in such cases grows exponentially, making the problem computationally challenging. Efficient algorithms leverage combinatorial optimization techniques to balance exploration and exploitation while managing the high-dimensional action space.

Finally, Bayesian bandits take a probabilistic approach, using prior knowledge about the arms' reward distributions to inform decision-making. As rewards are observed, beliefs about the distributions are updated, enabling the agent to balance exploration and exploitation through posterior sampling. Thompson Sampling is a prominent Bayesian method that selects arms based on their probability of being optimal given the observed data, making it particularly effective in uncertain environments with limited prior information.

Each of these extensions enriches the bandit framework, broadening its applicability to complex, real-world scenarios while introducing specialized challenges that demand innovative algorithmic solutions.

Regret analysis is a cornerstone of evaluating the performance of bandit algorithms, providing a quantitative measure of how much cumulative reward is lost by not always selecting the optimal arm. Regret measures the difference between the reward that could have been achieved by consistently playing the best arm and the reward obtained by the algorithm. This metric is crucial because it captures the trade-off between exploration (gathering information about less familiar arms) and exploitation (leveraging the current knowledge to maximize rewards).

In stochastic bandits, the asymptotic lower bound on regret is known as the optimal regret. This lower bound arises because, to confidently estimate the mean rewards of all arms, a sufficient number of samples must be taken from each suboptimal arm. The regret scales with the logarithm of the time horizon $T$ and is inversely proportional to the suboptimality gap $\Delta_k$, which measures the difference between the mean reward of the optimal arm and a given suboptimal arm. Algorithms must balance exploring suboptimal arms enough to estimate their rewards while focusing on exploiting the optimal arm to minimize regret. This trade-off results in an asymptotic regret bound of $R_T = \Omega\left(\sum_{k: \mu_k < \mu^*} \frac{\ln T}{\Delta_k}\right)$, which represents the best achievable performance for stochastic bandits.

The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm is a prime example of an approach that achieves near-optimal regret. UCB balances exploration and exploitation by maintaining confidence intervals around the estimated mean reward of each arm. The algorithm selects the arm with the highest upper confidence bound at each step, ensuring that arms with higher uncertainty are explored more often. This balance enables UCB to achieve a regret bound of $R_T = O\left(\sum_{k: \mu_k < \mu^*} \frac{\ln T}{\Delta_k}\right)$, which matches the theoretical lower bound asymptotically. This efficiency makes UCB a powerful and widely used algorithm in bandit problems.

The $\epsilon$-greedy algorithm, while simpler, demonstrates a different trade-off. It explores randomly with a fixed probability $\epsilon$ and exploits the current best-known arm otherwise. Although easy to implement, its fixed exploration rate can lead to suboptimal performance as the time horizon increases. The regret of the basic $\epsilon$-greedy algorithm scales as $R_T = O(T^{2/3})$, which is worse than UCB for large $T$. However, its simplicity and adaptability make it a useful baseline and a practical choice in some real-world scenarios.

In summary, regret analysis not only quantifies the effectiveness of bandit algorithms but also provides a framework for understanding the trade-offs between exploration and exploitation. Algorithms like UCB achieve near-optimal regret by dynamically adjusting their exploration based on uncertainty, while simpler heuristics like $\epsilon$-greedy offer intuitive yet less efficient solutions. These insights are fundamental to advancing decision-making systems in uncertain environments.

The following examples demonstrate practical solutions to bandit problems using Rust. First, we simulate a multi-armed bandit environment where each arm has a stochastic reward distribution. This setup forms the basis for testing different bandit strategies. Next, we implement common strategies like greedy, epsilon-greedy, and softmax to address the exploration-exploitation dilemma. Finally, we evaluate these strategies using cumulative rewards and regret to measure their performance.

This example demonstrates how to model a bandit environment in Rust, where each arm has an associated reward probability. The Bandit struct simulates stochastic rewards using the rand crate.

use rand::Rng;

// Define a bandit environment

struct Bandit {

arms: Vec<f64>, // Expected rewards for each arm

}

impl Bandit {

fn new(arms: Vec<f64>) -> Self {

Bandit { arms }

}

// Simulate pulling an arm

fn pull(&self, arm: usize) -> f64 {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

if rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0) < self.arms[arm] {

1.0 // Reward

} else {

0.0 // No reward

}

}

}

fn main() {

let bandit = Bandit::new(vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]); // Three arms with probabilities 0.2, 0.5, 0.8

let reward = bandit.pull(2); // Simulate pulling the third arm

println!("Reward: {}", reward);

}

The Bandit struct models a multi-armed bandit environment, where each arm has a fixed reward probability. The pull method simulates the stochastic nature of the problem by generating a random number and comparing it to the arm's reward probability. If the random number is less than the probability, the agent receives a reward. This setup captures the uncertainty and randomness characteristic of bandit problems, allowing us to test various strategies for decision-making.

This example implements the epsilon-greedy strategy, balancing exploration and exploitation by introducing a small probability $\epsilon$ for random exploration.

use rand::Rng;

fn epsilon_greedy(arms: &[f64], _counts: &mut [usize], rewards: &mut [f64], epsilon: f64) -> usize {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

if rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0) < epsilon {

// Exploration: choose a random arm

rng.gen_range(0..arms.len())

} else {

// Exploitation: choose the best-known arm

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

}

fn main() {

let arms = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8];

let mut counts = vec![0; arms.len()];

let mut rewards = vec![0.0; arms.len()];

let epsilon = 0.1;

let rounds = 1000;

for _ in 0..rounds {

let choice = epsilon_greedy(&arms, &mut counts, &mut rewards, epsilon);

counts[choice] += 1;

rewards[choice] += arms[choice]; // Simulated reward

}

println!("Counts: {:?}", counts);

println!("Estimated rewards: {:?}", rewards);

}

The epsilon-greedy strategy ensures exploration by selecting a random arm with probability $\epsilon$ and exploitation by choosing the arm with the highest observed reward otherwise. The code tracks the number of times each arm is pulled (counts) and the cumulative rewards for each arm (rewards). Over time, the strategy learns to favor the optimal arm while still occasionally exploring other arms, demonstrating the balance between exploration and exploitation.

This example calculates cumulative rewards and regret, providing quantitative insights into the effectiveness of different strategies.

use rand::Rng; // Import the Rng trait

use rand::thread_rng;

fn calculate_regret(arms: &[f64], counts: &[usize], optimal: f64) -> f64 {

let total_reward: f64 = counts

.iter()

.zip(arms)

.map(|(&count, &reward)| count as f64 * reward)

.sum();

let optimal_reward = optimal * counts.iter().sum::<usize>() as f64;

optimal_reward - total_reward

}

fn epsilon_greedy(arms: &[f64], _counts: &mut [usize], rewards: &mut [f64], epsilon: f64) -> usize {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

if rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0) < epsilon {

// Exploration: choose a random arm

rng.gen_range(0..arms.len())

} else {

// Exploitation: choose the best-known arm

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

}

fn main() {

let arms = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8];

let optimal = 0.8; // The best arm's expected reward

let mut counts = vec![0; arms.len()];

let mut rewards = vec![0.0; arms.len()];

let epsilon = 0.1;

let rounds = 1000;

for _ in 0..rounds {

let choice = epsilon_greedy(&arms, &mut counts, &mut rewards, epsilon);

counts[choice] += 1;

rewards[choice] += arms[choice];

}

let regret = calculate_regret(&arms, &counts, optimal);

println!("Cumulative regret: {}", regret);

}

The calculate_regret function evaluates the performance of a strategy by computing the difference between the cumulative rewards of an optimal strategy and the chosen strategy. This metric quantifies the cost of suboptimal decisions, offering a robust way to compare strategies. The code demonstrates how the epsilon-greedy strategy minimizes regret over time by learning to favor the optimal arm.

By combining theoretical insights, intuitive explanations, and hands-on Rust implementations, this section equips readers to understand, implement, and evaluate solutions to bandit problems, building a strong foundation for more advanced RL topics.

3.2. Greedy and Epsilon-Greedy Algorithms

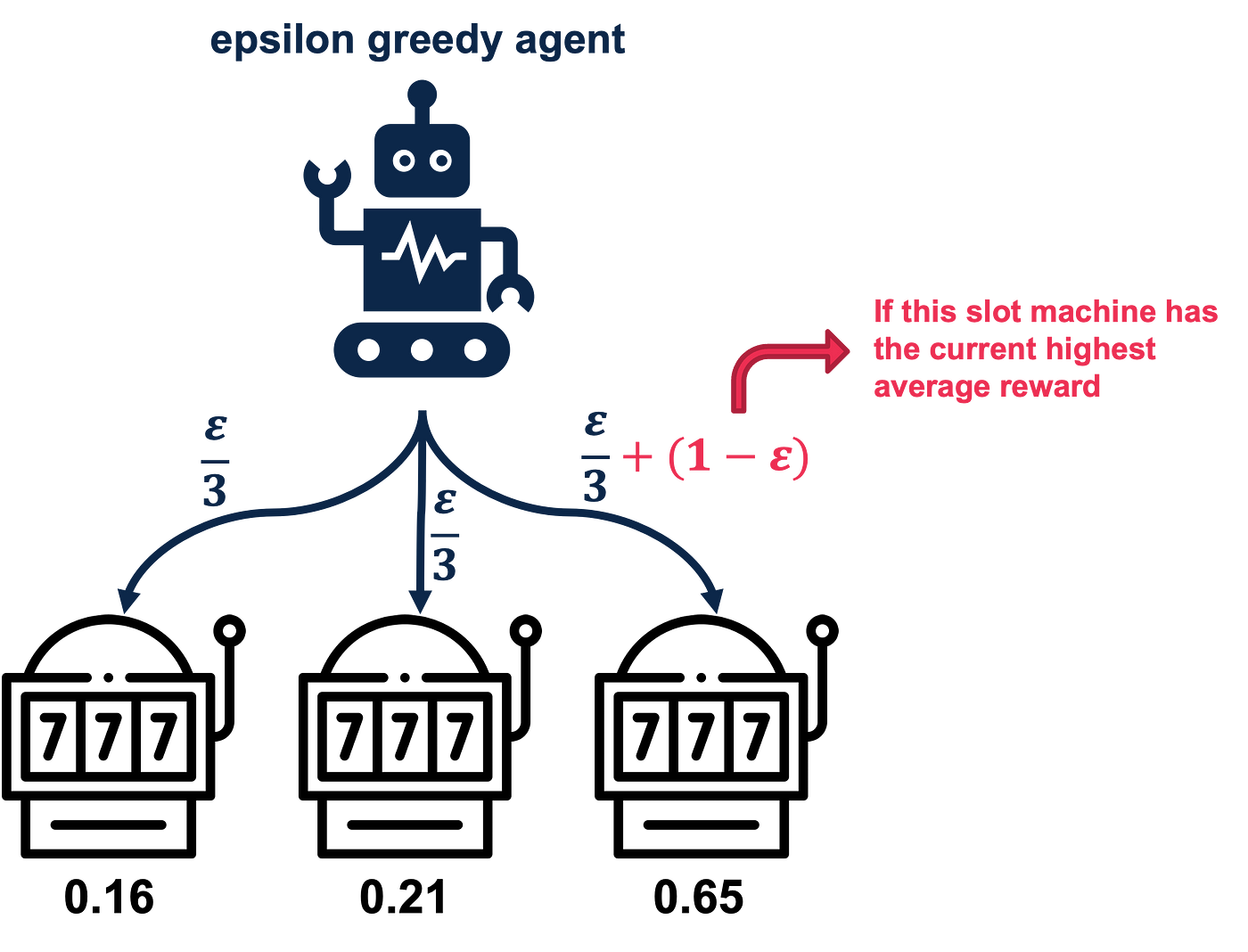

The epsilon-greedy algorithm, illustrated by the robot in the picture, is a strategy used to balance exploration and exploitation when faced with uncertain options. In this scenario, the robot is deciding which slot machine to play to maximize its rewards. The red arrow highlights the robot's tendency to exploit—the robot selects the machine with the highest average reward so far with a probability of $1 - \epsilon$ This is akin to sticking with what it already knows works well, maximizing immediate gains. However, to ensure it doesn’t miss out on discovering potentially better machines, the robot occasionally explores. With a small probability $\epsilon$, it randomly picks any of the other machines (splitting $\epsilon$ equally among them, as shown by the blue arrows). This exploration allows the robot to gather new information, which could lead to better long-term outcomes. Over time, the balance between exploration and exploitation ensures the robot can identify the best machine while minimizing the risk of missing better opportunities.

Figure 2: Illustration of epsilon greedy agent.

The epsilon-greedy algorithm, however, introduces a bit of exploration into the mix. Imagine you love the chocolate cake, but every so often, you let curiosity take over and sample something new, like the cheesecake or tiramisu. This occasional exploration (controlled by the "epsilon" factor) ensures you’re not overly fixated on your current favorite and helps you discover other potentially better options. Over time, you’ll have a better idea of all the desserts at the buffet, striking a balance between enjoying your current favorite and exploring for even better choices. This blend of exploration and exploitation makes epsilon-greedy a simple yet effective approach in many RL scenarios.

The greedy algorithm is one of the simplest strategies for decision-making in multi-armed bandit problems. It operates under a straightforward principle: always select the action (arm) with the highest observed average reward. Mathematically, if $\hat{\mu}_k$ represents the estimated mean reward for arm $k$, the greedy action $A_t$ at time $t$ is:

$$A_t = \arg\max_k \hat{\mu}_k.$$

The greedy algorithm focuses entirely on exploitation, assuming that the current estimates of rewards accurately reflect the true distribution. This approach may perform well in environments where the optimal arm is identified early. However, in stochastic settings where rewards are uncertain, it often fails to explore under-sampled arms, risking long-term suboptimal performance. For example, if an arm with high potential rewards is sampled only once and yields a low initial reward due to randomness, the greedy algorithm may permanently overlook it.

To address the limitations of the greedy algorithm, the epsilon-greedy algorithm introduces a mechanism for exploration. At each time step ttt, the algorithm selects a random action with probability $\epsilon$ (exploration) and the greedy action with probability $1 - \epsilon$ (exploitation). Formally, the action $A_t$ is chosen as:

$$ A_t = \begin{cases} \text{random arm, with probability } \epsilon, \\ \arg\max_k \hat{\mu}_k, \text{ with probability } 1 - \epsilon. \end{cases} $$

The parameter $\epsilon$ governs the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. A higher $\epsilon$ encourages exploration, which is crucial in early stages when the reward distributions are largely unknown. Conversely, a lower $\epsilon$ favors exploitation, making it more suitable for later stages when sufficient information about the arms has been gathered.

The purely greedy approach can lead to suboptimal long-term performance in bandit problems due to its lack of exploration. Suppose an arm $k$ has a true mean reward $\mu_k$ but yields an unusually low reward in early samples. A greedy strategy may prematurely discard $k$ in favor of seemingly better arms, even if further exploration would reveal its superiority. This behavior is mathematically reflected in high regret, as the algorithm may fail to converge to the optimal arm $\mu^* = \max_k \mu_k$.

The epsilon-greedy algorithm’s effectiveness lies in its ability to balance exploration and exploitation. The choice of $\epsilon$ significantly influences this balance. A large $\epsilon$ ensures that the algorithm explores extensively, reducing the risk of overlooking promising arms. However, excessive exploration delays convergence to the optimal arm. Conversely, a small $\epsilon$ accelerates exploitation but risks prematurely settling on suboptimal arms.

To understand this trade-off, consider regret, defined as:

$$ R_T = \sum_{t=1}^T \mu^* - \sum_{t=1}^T \mathbb{E}[R_t]. $$

A high $\epsilon$ minimizes regret early by exploring all arms but may lead to slower convergence later. The optimal value of $\epsilon$ depends on the problem's time horizon $T$ and the variability in rewards.

A dynamic approach to $\epsilon$, known as annealing, gradually decreases the exploration rate over time. This ensures that the agent explores extensively in the early stages but shifts toward exploitation as more information is gathered. A common annealing schedule reduces $\epsilon$ as a function of time $t$:

$$ \epsilon_t = \frac{\epsilon_0}{1 + \alpha t}, $$

where $\epsilon_0$ is the initial exploration rate and $\alpha$ controls the rate of decay. Annealing allows the epsilon-greedy algorithm to adapt to the learning process, balancing short-term exploration with long-term convergence.

The following implementations demonstrate greedy and epsilon-greedy algorithms in Rust. We simulate a multi-armed bandit problem, explore the effects of different $\epsilon$ values, and implement an annealing schedule to dynamically adjust $\epsilon$. These implementations showcase the practical trade-offs between exploration and exploitation in decision-making. The code below demonstrates the greedy algorithm, which always selects the arm with the highest observed reward.

fn greedy_action(rewards: &[f64]) -> usize {

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let rewards = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]; // Observed average rewards for three arms

let choice = greedy_action(&rewards); // Select the best arm

println!("Greedy choice: Arm {}", choice);

}

The greedy_action function selects the arm with the highest observed average reward using Rust’s iterator combinators. While simple and computationally efficient, this approach lacks any exploration mechanism, making it prone to suboptimal performance in stochastic environments.

This example balances exploration and exploitation using the epsilon-greedy strategy.

use rand::Rng;

fn epsilon_greedy(rewards: &[f64], epsilon: f64) -> usize {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

if rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0) < epsilon {

// Exploration: choose a random arm

rng.gen_range(0..rewards.len())

} else {

// Exploitation: choose the best arm

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

}

fn main() {

let rewards = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]; // Observed average rewards for three arms

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate

let choice = epsilon_greedy(&rewards, epsilon); // Select an arm

println!("Epsilon-greedy choice: Arm {}", choice);

}

The epsilon_greedy function introduces randomness by choosing a random arm with probability $\epsilon$. This ensures that the algorithm continues to explore under-sampled arms while exploiting the best-known arm most of the time. The balance between exploration and exploitation is controlled by the $\epsilon$ parameter.

This example incorporates an annealing schedule to dynamically adjust $\epsilon$ over time.

use rand::Rng;

fn annealing_epsilon(t: usize, epsilon_0: f64, alpha: f64) -> f64 {

epsilon_0 / (1.0 + alpha * t as f64)

}

fn epsilon_greedy_annealed(rewards: &[f64], epsilon: f64) -> usize {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

if rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0) < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..rewards.len()) // Exploration

} else {

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap() // Exploitation

}

}

fn main() {

let rewards = vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]; // Observed average rewards

let epsilon_0 = 0.1; // Initial epsilon

let alpha = 0.01; // Decay rate

for t in 0..100 {

let epsilon = annealing_epsilon(t, epsilon_0, alpha); // Update epsilon

let choice = epsilon_greedy_annealed(&rewards, epsilon); // Select an arm

println!("Time {}: Epsilon {:.3}, Choice: Arm {}", t, epsilon, choice);

}

}

The annealing_epsilon function computes a dynamically decreasing $\epsilon$ based on the time step $t$. This approach ensures that the agent explores extensively during early iterations but gradually shifts toward exploitation as it gains more information. The annealing schedule strikes a balance between short-term learning and long-term performance.

By integrating rigorous mathematical foundations with practical Rust implementations, this section equips readers with the tools to effectively design and evaluate greedy and epsilon-greedy algorithms, addressing the core challenges of exploration and exploitation in RL.

3.3. Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling

The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm is a clever and systematic way of addressing the challenge of exploration versus exploitation in multi-armed bandit problems. Think of it as trying to pick the best restaurant in a new city. While some restaurants might have great reviews (high observed rewards), there are others you haven't tried yet, and they might surprise you. UCB tackles this by assigning a "confidence score" to each restaurant based on two factors: how good the restaurant appears to be so far (observed reward) and how uncertain you are about its quality (how often you've tried it). If a restaurant has been tried a lot and consistently delivers good food, UCB will lean toward exploiting it. But if another restaurant hasn’t been tried much, UCB gives it a higher confidence score to encourage you to explore it, just in case it turns out to be even better. Over time, this method ensures that you don’t stick with familiar choices too early or miss out on hidden gems, achieving a balanced and informed decision-making process.

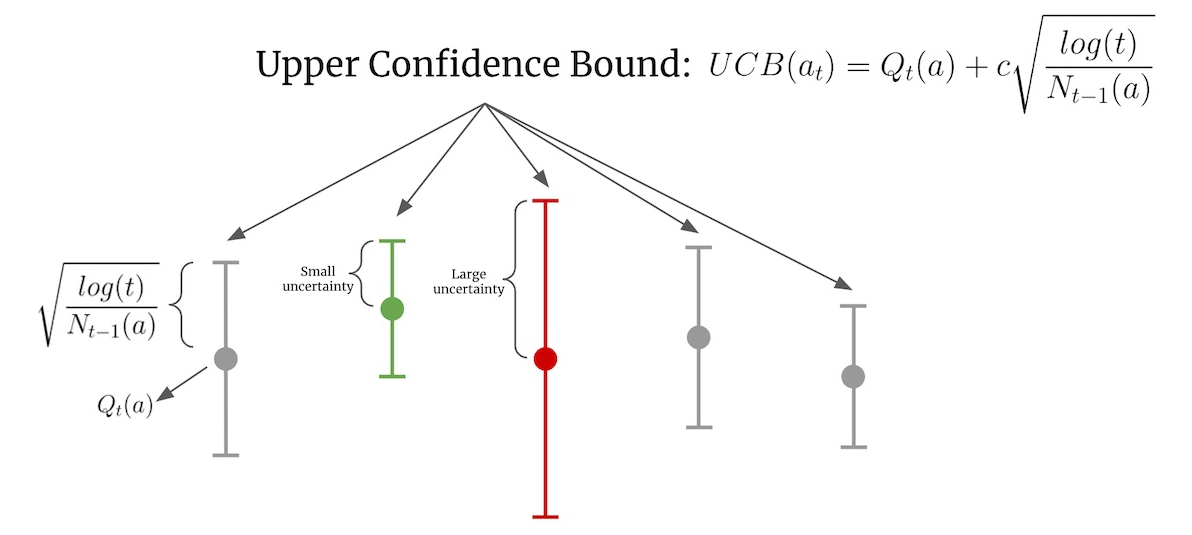

The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm, as illustrated in the image, balances exploration and exploitation by combining two key components for decision-making. The first component, $Q_t(a)$, represents the estimated reward for each action $a$, reflecting the known performance of that option. The second component, $c \sqrt{\frac{\log(t)}{N_{t-1}(a)}}$, accounts for uncertainty, increasing when an action aaa has been chosen fewer times ($N_{t-1}(a)$) or when fewer rounds ($t$) have occurred. Actions with smaller uncertainty intervals (e.g., actions frequently sampled) have narrower confidence bounds, emphasizing exploitation, while actions with larger uncertainty (e.g., less sampled or newer options) are prioritized for exploration. UCB ensures a systematic exploration of underexplored actions early on, while gradually focusing on actions that consistently yield high rewards as more data is gathered. This dynamic interplay makes UCB highly effective for balancing risk and reward in multi-armed bandit problems.

Figure 3: Illustration of UCB method.

Imagine you’re choosing between restaurants. Some are familiar and offer consistent experiences, while others are new and untested. The UCB algorithm balances revisiting your favorite spots (exploitation) with trying new places (exploration) by giving more weight to the uncertainty of the untested options. Mathematically, at each time step $t$, the algorithm selects the action $a_t$ as:

$$ a_t = \arg\max_k \left( \hat{\mu}_k + c \sqrt{\frac{\ln t}{n_k}} \right), $$

where:

$\hat{\mu}_k$ is the estimated mean reward of arm $k$.

$n_k$ is the number of times arm $k$ has been pulled.

$t$ is the total number of trials so far.

$c$ is a constant that determines the exploration strength.

The term $\sqrt{\frac{\ln t}{n_k}}$ adjusts the confidence interval for each arm. Arms with low $n_k$ (i.e., less exploration) have larger confidence intervals, prioritizing them for exploration. Over time, as $n_k$ increases, the confidence interval shrinks, reflecting growing certainty in the arm's estimated reward.

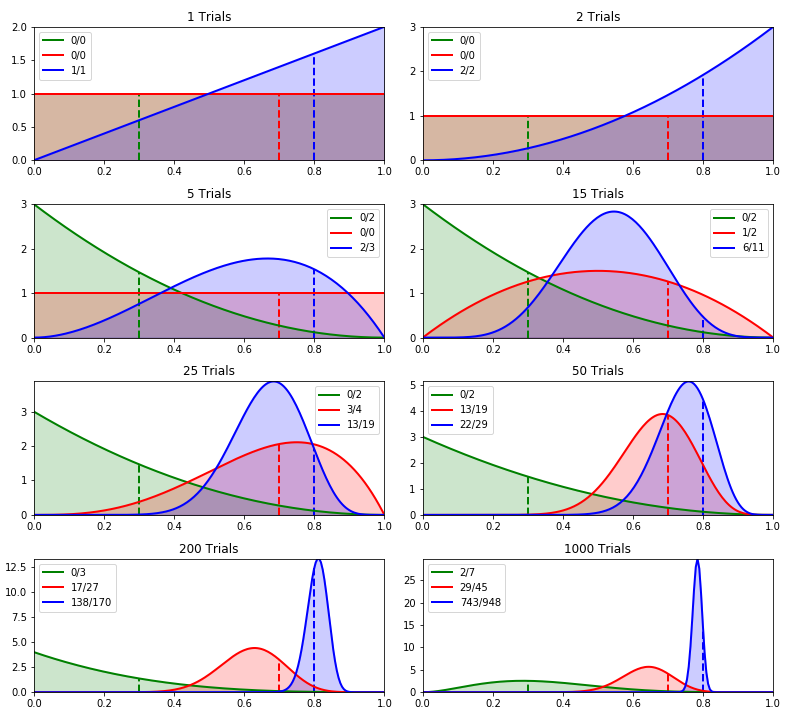

Thompson Sampling takes a probabilistic approach to balancing exploration and exploitation, rooted in Bayesian inference. Instead of relying on fixed confidence intervals, it models the uncertainty of each arm’s reward using probability distributions. At each time step, the algorithm samples from these distributions to select an arm, naturally encouraging exploration of uncertain arms and exploitation of well-understood ones.

Imagine you’re betting on horses, and you have some initial beliefs (priors) about each horse’s chances of winning. After observing several races, you update these beliefs based on performance (posterior distributions). When deciding which horse to bet on, you sample from your updated beliefs. Horses with both high potential and uncertainty are more likely to be chosen, reflecting Thompson Sampling’s balance between exploration and exploitation. These beliefs are shown in the image as the prior distributions for each arm (horse). After observing several races, you update your beliefs based on the horses’ performance—successful races sharpen the distribution peaks (like the blue horse), while poorly performing horses retain flatter, more uncertain distributions (like the green horse). Each time you decide which horse to bet on, you sample from these updated beliefs. This approach ensures that you not only favor horses with strong evidence of success but also occasionally bet on those with higher uncertainty, as they might reveal unexpected potential. Thompson Sampling works exactly like this, balancing exploration of less-tested options and exploitation of known performers, leading to smarter decisions over time.

Figure 4: An illustration of Thompson sampling method.

Formally, Thompson Sampling models the reward $R_k$ for each arm $k$ as a random variable with a prior distribution, such as Beta for binary rewards. At each time $t$, the algorithm:

Samples $\theta_k$ from the posterior distribution of arm $k$.

Selects the arm $A_t = \arg\max_k \theta_k$.

For binary rewards (success or failure), the Beta distribution is commonly used, and the posterior update is:

$$ \text{Beta}(\alpha_k, \beta_k) \rightarrow \text{Beta}(\alpha_k + \text{successes}, \beta_k + \text{failures}), $$

where $\alpha_k$ and $\beta_k$ represent the number of successes and failures, respectively. This Bayesian framework enables Thompson Sampling to dynamically adjust its exploration based on observed outcomes.

Both UCB and Thompson Sampling are theoretically guaranteed to achieve logarithmic regret over time, meaning their performance approaches that of the optimal strategy as the time horizon $T$ increases. Regret, a key metric in bandit problems, measures the difference between the cumulative reward of the optimal strategy and the chosen strategy:

$$ R_T = \sum_{t=1}^T \mu^* - \sum_{t=1}^T \mathbb{E}[R_t], $$

where $\mu^*$ is the reward of the best arm.

The logarithmic regret of UCB and Thompson Sampling ensures that they perform near-optimally in the long run, with their exploration strategies focusing on under-sampled arms only when necessary. For UCB, this is achieved by systematically narrowing confidence intervals. For Thompson Sampling, the posterior distributions naturally shift toward the true reward probabilities, reducing unnecessary exploration.

The confidence interval in UCB plays a pivotal role in its exploration strategy. The term $\sqrt{\frac{\ln t}{n_k}}$ is analogous to a measure of doubt about an arm’s reward. Arms with fewer samples have wider intervals, signaling greater uncertainty. As more data is collected ($n_k$ increases), this term diminishes, indicating growing confidence in the estimated reward.

Imagine you’re reviewing movies on a streaming platform. New releases with few reviews have uncertain ratings, warranting exploration to improve the platform’s recommendations. Older movies with many reviews have stable ratings, requiring less exploration. UCB dynamically adjusts its exploration effort based on this confidence, ensuring efficient resource allocation.

Thompson Sampling’s Bayesian nature offers several advantages. By maintaining a distribution over possible rewards for each arm, it captures both the uncertainty and observed performance of the arms. For instance:

Arms with limited data retain wider distributions, reflecting uncertainty.

Arms with consistent outcomes develop narrower distributions, emphasizing exploitation.

This probabilistic framework allows Thompson Sampling to seamlessly incorporate new information and make decisions that balance exploration and exploitation without requiring explicit confidence intervals.

The following implementations showcase UCB and Thompson Sampling algorithms in Rust. The first example demonstrates how UCB calculates confidence bounds for action selection. The second example implements Thompson Sampling using Beta distributions for posterior updates. Finally, both algorithms are compared in a simulated bandit environment to analyze their performance in terms of cumulative rewards and regret.

This code calculates confidence bounds and selects actions using the UCB formula.

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.5"

use rand::Rng;

fn ucb_action(rewards: &[f64], counts: &[usize], total_trials: usize, c: f64) -> usize {

rewards

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(k, &reward)| {

if counts[k] == 0 {

f64::INFINITY // Prioritize unexplored arms

} else {

reward + c * ((total_trials as f64).ln() / counts[k] as f64).sqrt()

}

})

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let mut rewards = vec![0.0; 3];

let mut counts = vec![0; 3];

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let c = 2.0;

let rounds = 1000;

for t in 1..=rounds {

let choice = ucb_action(&rewards, &counts, t, c);

counts[choice] += 1;

let reward: f64 = if rng.gen::<f64>() < 0.5 + 0.2 * choice as f64 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 };

rewards[choice] += (reward - rewards[choice]) / counts[choice] as f64;

}

println!("Final counts: {:?}", counts);

println!("Final rewards: {:?}", rewards);

}

This UCB implementation dynamically balances exploration and exploitation by prioritizing arms with higher uncertainty. The confidence bound shrinks as arms are sampled more frequently, allowing the algorithm to focus on the best-performing arms over time.

This code demonstrates Thompson Sampling for binary rewards using Beta distributions.

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.5"

rand_distr = "0.4.3"

use rand::prelude::*;

use rand_distr::{Distribution, Beta}; // Note: using rand_distr instead of rand::distributions

fn thompson_sampling(priors: &mut [(f64, f64)]) -> usize {

priors

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(k, &(alpha, beta))| {

let beta_dist = Beta::new(alpha, beta).unwrap();

let sample = beta_dist.sample(&mut rand::thread_rng());

(k, sample)

})

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let mut priors = vec![(1.0, 1.0); 3]; // Initial priors for three arms

let rounds = 1000;

for _ in 0..rounds {

let choice = thompson_sampling(&mut priors);

// Simulate rewards: higher index arms have higher probability of success

let reward: f64 = if rand::thread_rng().gen::<f64>() < 0.5 + 0.2 * choice as f64 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 };

if reward > 0.0 {

priors[choice].0 += 1.0; // Update successes (alpha)

} else {

priors[choice].1 += 1.0; // Update failures (beta)

}

}

println!("Final priors: {:?}", priors);

}

Thompson Sampling leverages Bayesian inference to maintain posterior distributions for each arm. By sampling from these distributions, it dynamically balances exploration of uncertain arms with exploitation of high-reward arms.

This simulation compares the algorithms' cumulative rewards and regret over time, highlighting their efficiency and adaptability. By combining rigorous mathematical insights with practical implementations, this section equips readers with a robust understanding of UCB and Thompson Sampling for reinforcement learning.

3.4. Contextual Bandits

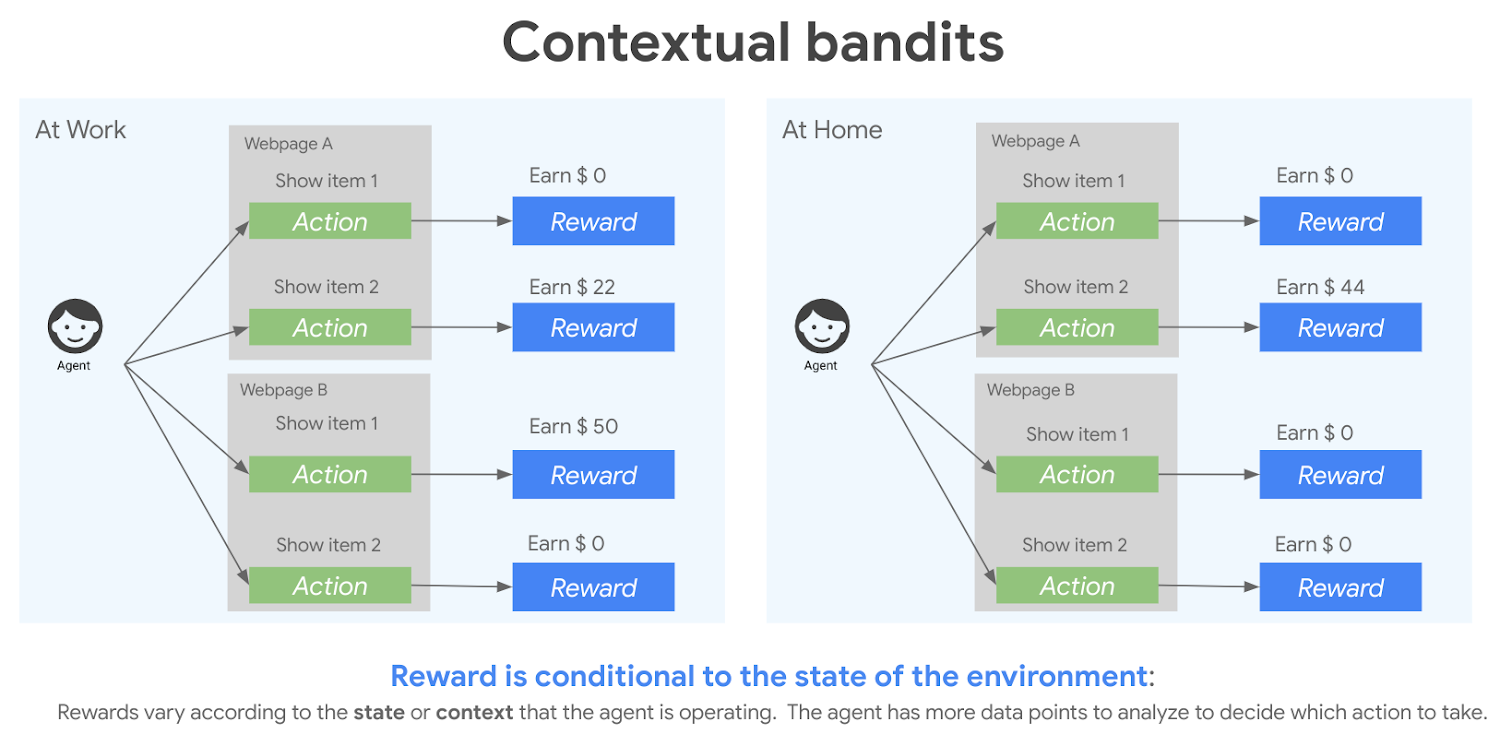

The contextual bandit framework, as illustrated in the image, showcases how decision-making is influenced by the surrounding context. Imagine an agent tasked with recommending items on a webpage. The environment presents different states, such as "At Work" or "At Home," which define the context. For each context, the agent selects an action—showing specific items on the webpage—and receives a reward based on the effectiveness of the recommendation. For instance, at work, showing item 2 on webpage A earns $22, while at home, showing the same item earns $44. This demonstrates how the reward is conditional on both the action taken and the contextual information. The goal of the agent is to learn a policy that dynamically adapts its decisions to maximize cumulative rewards by leveraging the context, making contextual bandits a powerful tool for personalized and adaptive decision-making.

Figure 5: Illustration of contextual bandit method.

The contextual bandit problem represents a sophisticated extension of the traditional multi-armed bandit framework, integrating contextual information to enable more informed decision-making. Unlike the basic multi-armed bandit setting, where the agent selects actions based solely on past rewards, the contextual bandit incorporates an additional layer of complexity: the context. At each time step $t$, the agent receives a context vector $\mathbf{x}_t \in \mathbb{R}^d$, representing the state or features of the current environment. Based on this context, the agent selects an action $A_t \in \mathcal{A}$, where $\mathcal{A}$ is the set of available actions, and subsequently observes a reward $R_t(A_t)$. The objective is to learn a policy $\pi: \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathcal{A}$ that maps contexts to actions in a way that maximizes the cumulative reward over $T$ time steps:

$$ G_T = \sum_{t=1}^T R_t(A_t). $$

This framework significantly expands the scope of the bandit problem, enabling agents to make decisions that are not only influenced by the history of actions and rewards but also tailored to the specific circumstances of each decision.

A compelling analogy for the contextual bandit is personalized advertising. Imagine an online platform that must decide which advertisement to display to users visiting its website. Each user brings specific attributes, such as browsing history, geographic location, and expressed interests—this is the context $\mathbf{x}_t$. The platform acts as the agent, selecting an advertisement (action $A_t$) to display, and the reward $R_t(A_t)$ could be whether the user clicks on the ad. Unlike traditional bandits that treat all users identically, contextual bandits allow the platform to leverage user-specific information to make tailored decisions. For instance, showing travel-related ads to users who have recently searched for flights is more likely to result in a click compared to generic ads. By continually learning the relationship between user contexts and the effectiveness of different ads, the platform improves its decision-making over time, maximizing engagement and revenue.

From a mathematical standpoint, the contextual bandit problem balances the exploration-exploitation trade-off in the presence of rich contextual information. For a given context-action pair $(\mathbf{x}_t, A_t)$, the expected reward is modeled as $\mathbb{E}[R_t(A_t) | \mathbf{x}_t, A_t] = f(\mathbf{x}_t, A_t)$, where $f$ is an unknown function. The challenge lies in estimating $f$ accurately while actively sampling actions to gather informative data. Many contextual bandit algorithms, such as LinUCB (Linear Upper Confidence Bound), assume that $f$ is linear and approximate the reward function as:

$$\hat{R}_t(A_t) = \mathbf{x}_t^\top \theta_{A_t},$$

where $\theta_{A_t}$ is a parameter vector specific to action $A_t$. The agent maintains uncertainty estimates for each action's parameter vector, enabling it to explore actions with high uncertainty while exploiting those with high estimated rewards. This is analogous to personalized advertising platforms experimenting with less-tested ads for new user profiles while capitalizing on well-performing ads for familiar contexts.

Beyond advertising, the contextual bandit framework applies to diverse real-world scenarios, including recommendation systems, healthcare (e.g., recommending treatments based on patient data), and finance (e.g., portfolio allocation based on market conditions). The ability to adapt actions to contextual signals makes this approach indispensable for decision-making in dynamic and uncertain environments. By leveraging the interplay between context, action, and reward, contextual bandits push the boundaries of intelligent decision-making.

While contextual bandits extend traditional bandits by incorporating context, they differ fundamentally from full reinforcement learning (RL) problems due to the absence of sequential dependencies. In contextual bandits, each decision is independent, and the chosen action affects only the immediate reward. Formally, the agent solves a sequence of independent optimization problems:

$$ \text{Given } \mathbf{x}_t, \text{ choose } A_t \text{ to maximize } \mathbb{E}[R_t(A_t) | \mathbf{x}_t]. $$

In full RL, however, actions influence not only immediate rewards but also future states and available actions, creating a complex feedback loop. This distinction is analogous to playing a one-off game versus a multi-stage tournament. In a one-off game (contextual bandits), your strategy depends solely on the current situation. In a tournament (full RL), you must also consider how your actions affect your position in subsequent rounds.

Contextual bandits are widely used in applications where decisions are influenced by contextual information. Some notable examples include:

Personalized Recommendations: E-commerce platforms leverage contextual bandits to recommend products based on user preferences. For instance, recommending a smartphone (action) based on browsing history, price sensitivity, and brand affinity (context) aims to maximize purchases (reward).

Adaptive Clinical Trials: In healthcare, contextual bandits allocate treatments (actions) to patients based on their characteristics (context), such as age, medical history, and genetic markers, to maximize recovery rates (reward) while minimizing harmful side effects.

Dynamic Pricing: Online retailers use contextual bandits to optimize prices (actions) based on market trends, competitor prices, and customer behavior (context), aiming to maximize revenue (reward).

These applications highlight the versatility of contextual bandits in dynamically adapting decisions based on contextual cues.

In contextual bandits, the additional information provided by the context $\mathbf{x}_t$ enables the agent to tailor its actions to specific situations, improving decision quality. The reward for an action depends on both the action itself and the context:

$$ R_t(A_t) = f(\mathbf{x}_t, A_t) + \epsilon, $$

where $f(\mathbf{x}_t, A_t)$ represents the expected reward given the context and action, and $\epsilon$ is random noise. This relationship allows the agent to capture patterns between contexts and rewards, enabling more precise predictions.

An analogy is a chef designing meals for customers. The customer’s preferences and dietary restrictions (context) influence their satisfaction (reward) with a given dish (action). A chef who ignores this context might offer random dishes, while one who considers preferences can craft meals that delight customers.

Despite their advantages, contextual bandits present several challenges:

Efficient Context Processing: Processing high-dimensional context vectors $\mathbf{x}_t$ requires computational efficiency. As the dimensionality increases, algorithms must handle the curse of dimensionality, where irrelevant features dilute the predictive power.

High-Dimensional Contexts: In many real-world scenarios, context vectors may include hundreds or thousands of features. Identifying and leveraging the most relevant features is critical for efficient decision-making.

Feature Selection and Representation: Choosing the right features and representing them effectively can significantly improve the performance of contextual bandit algorithms. For instance, combining raw features into meaningful representations (e.g., embeddings in machine learning) can enhance predictive accuracy.

These challenges are akin to solving a puzzle with extra pieces that don’t belong—understanding which pieces matter and how they fit together is essential for success.

The following examples implement a contextual bandit algorithm in Rust. The first example integrates context into the decision-making process, demonstrating how rewards depend on both actions and contexts. The second example evaluates the effect of different context representations on algorithm performance. Finally, the third example applies contextual bandits to a personalized recommendation problem, showcasing their real-world applicability.

This implementation models a contextual bandit problem where rewards are determined by the interaction between context and actions.

use rand::Rng;

// Define a simple contextual bandit environment

struct ContextualBandit {

contexts: Vec<Vec<f64>>, // Context vectors

rewards: Vec<Vec<f64>>, // Rewards for each action given context

}

impl ContextualBandit {

fn new(contexts: Vec<Vec<f64>>, rewards: Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Self {

Self { contexts, rewards }

}

fn get_context(&self, t: usize) -> &Vec<f64> {

&self.contexts[t % self.contexts.len()]

}

fn get_reward(&self, t: usize, action: usize) -> f64 {

self.rewards[t % self.rewards.len()][action]

}

}

fn main() {

let contexts = vec![vec![0.1, 0.2], vec![0.5, 0.8], vec![0.9, 0.4]];

let rewards = vec![vec![1.0, 0.5], vec![0.6, 0.8], vec![0.3, 0.9]];

let bandit = ContextualBandit::new(contexts, rewards);

let rounds = 10;

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for t in 0..rounds {

let context = bandit.get_context(t);

let action = rng.gen_range(0..2); // Random action selection

let reward = bandit.get_reward(t, action);

println!(

"Round {}: Context {:?}, Action {}, Reward {}",

t, context, action, reward

);

}

}

This example simulates a contextual bandit environment with predefined contexts and rewards. At each round, the agent observes a context, selects an action (randomly in this example), and receives a reward based on the action and context. The model serves as a foundation for developing more advanced algorithms.

This example explores the role of context representation in predicting rewards.

fn linear_model(context: &[f64], weights: &[f64]) -> f64 {

context.iter().zip(weights).map(|(x, w)| x * w).sum()

}

fn main() {

let contexts = vec![vec![0.1, 0.2], vec![0.5, 0.8], vec![0.9, 0.4]];

let weights = vec![0.6, 0.4];

for context in &contexts {

let prediction = linear_model(context, &weights);

println!("Context {:?}, Prediction {}", context, prediction);

}

}

The linear model predicts rewards as a weighted sum of context features. This example highlights how feature selection and representation influence the algorithm’s performance. By adjusting weights or feature selection, one can optimize the model’s accuracy.

This example applies contextual bandits to a recommendation scenario.

fn linear_model(context: &[f64], weights: &[f64]) -> f64 {

context.iter().zip(weights.iter()).map(|(c, w)| c * w).sum()

}

fn personalized_recommendation(context: &[f64], weights: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> usize {

weights

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(i, w)| (i, linear_model(context, w)))

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(i, _)| i)

.unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let contexts = vec![vec![0.1, 0.2], vec![0.5, 0.8], vec![0.9, 0.4]];

let weights = vec![vec![0.7, 0.3], vec![0.4, 0.6]];

for context in &contexts {

let recommendation = personalized_recommendation(context, &weights);

println!("Context {:?}, Recommended action {}", context, recommendation);

}

}

The personalized recommendation algorithm predicts rewards for each action based on context features and selects the action with the highest predicted reward. This example demonstrates how contextual bandits can optimize decisions in dynamic, context-rich environments.

By combining a rigorous theoretical foundation with practical Rust implementations, this section provides readers or RLVR with a comprehensive understanding of contextual bandits and their applications, preparing them to tackle real-world challenges in reinforcement learning.

3.5. Conclusion

Chapter 3 provides a comprehensive exploration of bandit algorithms and the exploration-exploitation dilemma, equipping you with the knowledge and tools to implement and evaluate these algorithms using Rust. By mastering these concepts, you will be well-prepared to tackle more complex reinforcement learning challenges, leveraging the power of Rust to build efficient and effective RL systems.

3.5.1. Further Learning with GenAI

These prompts are designed to guide you through the complexities of bandit algorithms and the exploration-exploitation dilemma, enabling you to gain a deep and comprehensive understanding of these critical concepts in reinforcement learning.

Analyze the fundamental principles of the multi-armed bandit problem. How does the trade-off between exploration and exploitation manifest in this problem, and what are the key metrics used to evaluate bandit algorithms? Implement a basic multi-armed bandit problem in Rust to illustrate these concepts.

Discuss the exploration-exploitation dilemma in reinforcement learning. How do different strategies, such as greedy, epsilon-greedy, and softmax action selection, address this dilemma? Implement these strategies in Rust and compare their effectiveness in a simulated bandit problem.

Explore the concept of regret in bandit problems. How is regret defined and measured, and why is it a critical metric for evaluating the performance of bandit algorithms? Implement a Rust-based simulation to calculate and analyze regret across different bandit strategies.

Examine the epsilon-greedy algorithm in detail. How does the value of epsilon influence the balance between exploration and exploitation, and what are the trade-offs involved? Implement an epsilon-greedy algorithm in Rust, experimenting with different values of epsilon and their effects on cumulative reward.

Discuss the concept of annealing in the epsilon-greedy algorithm. How can dynamically adjusting epsilon over time improve the algorithm’s performance? Implement an annealing schedule in Rust and analyze its impact on exploration and exploitation.

Analyze the limitations of purely greedy approaches in bandit problems. How does the lack of exploration affect long-term performance, and how can this be mitigated? Implement a comparison between a greedy algorithm and more exploratory approaches in Rust, focusing on cumulative reward and regret.

Explore the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm. How does UCB balance exploration and exploitation through confidence intervals, and what are the theoretical guarantees associated with it? Implement the UCB algorithm in Rust and evaluate its performance in various bandit scenarios.

Discuss the mathematical foundations of the UCB algorithm. How are confidence bounds calculated, and what role do they play in action selection? Implement these calculations in Rust and explore their impact on the algorithm’s decisions.

Examine the Thompson Sampling algorithm from a Bayesian perspective. How does Thompson Sampling leverage prior distributions to balance exploration and exploitation, and what are the advantages of this approach? Implement Thompson Sampling in Rust and compare its performance with UCB in a multi-armed bandit problem.

Discuss the role of prior distributions in Thompson Sampling. How are these priors updated with observed data, and how do they influence the algorithm’s decision-making process? Implement a Rust-based model for updating priors in Thompson Sampling and analyze its impact on performance.

Explore the concept of logarithmic regret bounds in bandit algorithms. How do UCB and Thompson Sampling achieve these bounds, and why are they significant in evaluating algorithm performance? Implement a Rust simulation to compare the regret of different bandit algorithms over time.

Analyze the concept of contextual bandits. How do contextual bandits differ from traditional bandit problems, and what role does context play in decision-making? Implement a contextual bandit algorithm in Rust and apply it to a problem involving personalized recommendations.

Discuss the trade-offs and challenges in contextual bandits. How does the addition of context influence the complexity of the problem, and what strategies can be used to handle high-dimensional contexts? Implement different context representation techniques in Rust and evaluate their impact on performance.

Explore the applications of contextual bandits in real-world scenarios. How are contextual bandits used in fields such as healthcare, finance, and online advertising? Implement a Rust-based contextual bandit model for one of these applications and analyze its effectiveness.

Examine the role of feature selection in contextual bandits. How does the choice of features affect the performance of the algorithm, and what techniques can be used to optimize feature selection? Implement a feature selection strategy in Rust and evaluate its impact on a contextual bandit problem.

Discuss the importance of scalability in bandit algorithms. How can Rust’s performance capabilities be leveraged to implement bandit algorithms that scale efficiently with large numbers of arms or high-dimensional contexts? Implement and benchmark a scalable bandit algorithm in Rust.

Explore the concept of exploration-exploitation trade-offs in continuous action spaces. How do bandit algorithms like UCB and Thompson Sampling adapt to problems with continuous actions? Implement a continuous action bandit problem in Rust and experiment with different algorithms.

Discuss the challenges of balancing exploration and exploitation in non-stationary environments. How do bandit algorithms need to be adapted to handle changes in the underlying reward distributions? Implement a Rust-based model for a non-stationary bandit problem and analyze the effectiveness of different strategies.

Examine the concept of regret minimization in the context of adversarial bandits. How do algorithms like EXP3 address the challenges posed by adversarial settings, and what are the key differences from stochastic bandit problems? Implement the EXP3 algorithm in Rust and compare its performance with stochastic algorithms.

Discuss the potential ethical considerations when applying bandit algorithms in real-world settings. How can biases in data or reward structures lead to unfair outcomes, and what strategies can be implemented to mitigate these risks? Implement a Rust-based bandit model with fairness constraints and evaluate its performance.

By engaging with these robust and comprehensive questions, you will gain deep insights into the mathematical foundations, algorithmic strategies, and practical implementations of bandit problems using Rust.

3.5.2. Hands On Practices

These exercises are structured to encourage hands-on experimentation and deep engagement with the topics, enabling readers to apply their knowledge in practical ways using Rust.

Exercise 3.1: Implementing and Comparing Bandit Algorithms

Task:

Implement the greedy, epsilon-greedy, and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithms in Rust for a multi-armed bandit problem.

Set up a simulation environment with multiple arms, each with different reward distributions.

Challenge:

Compare the performance of these algorithms in terms of cumulative reward and regret. Experiment with different values of epsilon for the epsilon-greedy algorithm and different confidence levels for UCB.

Analyze how each algorithm handles the exploration-exploitation trade-off and how their performance changes over time.

Exercise 3.2: Developing a Thompson Sampling Model

Task:

Implement the Thompson Sampling algorithm in Rust for a multi-armed bandit problem. Focus on the Bayesian approach, including prior distribution initialization and posterior updates based on observed rewards.

Challenge:

Test the Thompson Sampling model across different scenarios with varying numbers of arms and reward distributions. Compare its performance with the UCB algorithm, focusing on cumulative reward and regret.

Explore how different prior distributions (e.g., Beta, Gaussian) impact the model's performance and decision-making process.

Exercise 3.3: Exploring Contextual Bandits in a Real-World Scenario

Task:

Implement a contextual bandit algorithm in Rust that incorporates additional context (e.g., user preferences, environmental factors) into the decision-making process.

Choose a real-world scenario, such as personalized content recommendation, where context plays a significant role.

Challenge:

Experiment with different context representations, such as feature vectors or embeddings, and analyze their impact on the algorithm’s performance.

Evaluate the effectiveness of your contextual bandit model by comparing it to a non-contextual bandit approach, focusing on metrics like accuracy, cumulative reward, and adaptation to new contexts.

Exercise 3.4: Implementing and Analyzing Annealing in Epsilon-Greedy Algorithms

Task:

Implement an epsilon-greedy algorithm in Rust with an annealing schedule that gradually reduces epsilon over time, shifting from exploration to exploitation.

Challenge:

Run simulations to compare the annealing epsilon-greedy algorithm with a static epsilon-greedy approach. Analyze how the annealing schedule impacts cumulative reward, regret, and the algorithm's ability to converge to the optimal arm.

Experiment with different annealing schedules (e.g., linear decay, exponential decay) and observe their effects on the balance between exploration and exploitation.

Exercise 3.5: Addressing Non-Stationary Bandit Problems

Task:

Implement a Rust-based bandit algorithm that adapts to non-stationary environments, where the reward distributions of the arms change over time.

Challenge:

Implement techniques such as sliding window UCB or discounted Thompson Sampling to handle the non-stationarity. Test these techniques on a bandit problem with varying reward distributions.

Analyze how quickly and effectively the algorithm adapts to changes in the environment, focusing on metrics like regret, adaptation speed, and long-term performance stability.

By implementing these techniques in Rust and experimenting with different scenarios and parameters, you will gain valuable insights into the complexities and nuances of decision-making under uncertainty in reinforcement learning.

Comments