Chapter 5

Monte Carlo Methods

"Monte Carlo methods, by leveraging the power of random sampling, offer a flexible approach to solving complex reinforcement learning problems where traditional methods may struggle." — Andrew Ng

Chapter 5 of RLVR delves into Monte Carlo (MC) methods, a powerful class of algorithms in reinforcement learning that rely on repeated random sampling to estimate the value of states or actions. This chapter begins by introducing the fundamental concepts of MC methods, emphasizing their importance in situations where a model of the environment is unavailable. Readers will explore the difference between first-visit and every-visit Monte Carlo methods and understand how these approaches are used to evaluate policies through sampled episodes. Practical Rust implementations guide readers through creating simulations and estimating value functions, allowing them to see firsthand the impact of different sampling strategies. The chapter continues with a detailed examination of Monte Carlo policy evaluation and improvement, where readers learn to implement both on-policy and off-policy methods, using techniques like importance sampling to correct for distribution differences. The chapter then explores Monte Carlo control, where policy evaluation and improvement are combined to converge on the optimal policy, highlighting the importance of exploration strategies such as epsilon-soft policies and exploring starts. Finally, the chapter addresses the challenges and limitations of Monte Carlo methods, such as data inefficiency and slow convergence, offering insights into how these issues can be mitigated through hybrid approaches and alternative techniques like Temporal Difference (TD) learning. Through this comprehensive overview, readers will gain a deep understanding of Monte Carlo methods and develop the skills to implement, analyze, and optimize these algorithms using Rust.

5.1. Introduction to Monte Carlo Methods

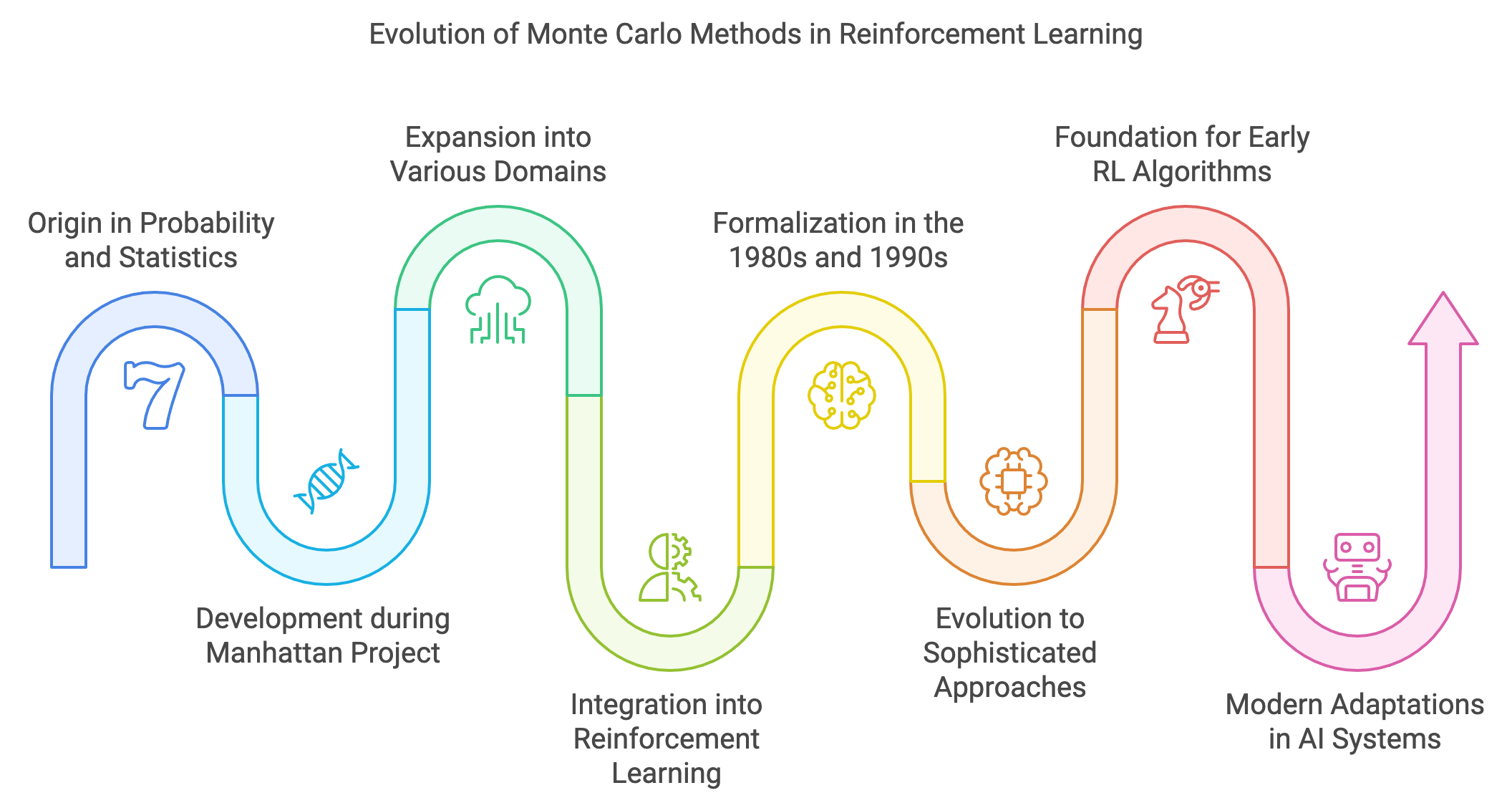

Monte Carlo (MC) methods originated from the field of probability and statistics, with their name inspired by the Monte Carlo Casino in Monaco, reflecting the methods' reliance on randomness. Their roots can be traced back to the 1940s during the Manhattan Project, where scientists like Stanislaw Ulam and John von Neumann used random sampling techniques to solve complex integrals and simulate neutron diffusion processes. Over the years, Monte Carlo methods expanded into various domains, including physics, finance, and optimization, for solving problems that were analytically intractable.

Figure 1: Historical journey of Monte Carlo methods in Reinforcement Learning.

In the context of reinforcement learning (RL), the integration of Monte Carlo methods began as part of the broader quest to solve sequential decision-making problems in uncertain environments. Early works on RL, including seminal contributions by Richard Bellman in dynamic programming, focused on model-based approaches requiring knowledge of environment dynamics. However, as researchers encountered environments where models were unknown or too complex to compute, the appeal of model-free methods like Monte Carlo grew.

The adoption of Monte Carlo in RL was catalyzed by its ability to estimate the value of states or actions based on observed episodes of interaction. This was a major breakthrough because it eliminated the need for explicit environment models, which are often difficult to construct. Monte Carlo methods were formalized in the 1980s and 1990s as part of the broader development of RL, notably in works like Sutton and Barto’s foundational book, "Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction." These methods enabled agents to learn from experience by averaging returns observed in episodes that started from specific states or executed particular actions.

Monte Carlo methods in RL have since evolved significantly, transitioning from basic episodic algorithms to more sophisticated approaches integrated with function approximation and neural networks. They formed the foundation for many early RL algorithms, such as Monte Carlo control and Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS), which has been widely used in game-playing AI, including AlphaGo. Unlike early methods that focused on tabular representations, modern adaptations leverage MC techniques with deep neural networks to handle large and continuous state spaces, paving the way for breakthroughs in robotics, healthcare, and complex decision-making tasks.

Today, Monte Carlo methods remain a cornerstone in RL, valued for their simplicity, model-free nature, and effectiveness in solving problems where exploration and stochasticity are crucial. They exemplify how stochastic principles, combined with computational power, have transformed the way intelligent systems learn and make decisions. The historical journey of Monte Carlo methods in RL underscores their evolution from theoretical probability tools to practical algorithms that empower modern AI systems.

Monte Carlo (MC) methods are a class of algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to compute numerical results. These methods are particularly effective for solving problems where direct analytical solutions are infeasible or computationally expensive. In the context of reinforcement learning (RL), Monte Carlo methods estimate the value of states or actions by using sampled episodes of interaction with the environment. Unlike dynamic programming, which requires a complete model of the environment (e.g., transition probabilities), Monte Carlo methods work directly with experience, making them model-free.

Mathematically, Monte Carlo methods estimate the value function $V^\pi(s)$ for a policy $\pi$ by averaging the returns observed from multiple episodes starting from state $s$. The return $G_t$ is defined as the cumulative reward from time $t$ onward:

$$ G_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma R_{t+2} + \gamma^2 R_{t+3} + \dots = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \gamma^k R_{t+k+1}, $$

where $\gamma$ is the discount factor. Given a sufficient number of sampled episodes, the Monte Carlo estimate for $V^\pi(s)$ converges to its true value:

$$ V^\pi(s) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $G_t^{(i)}$ is the return observed in the $i$-th episode, and $N$ is the total number of episodes.

An intuitive analogy for Monte Carlo methods is estimating the average grade of a class by sampling a subset of students and calculating the average of their scores. The more students you sample, the closer your estimate will be to the true class average.

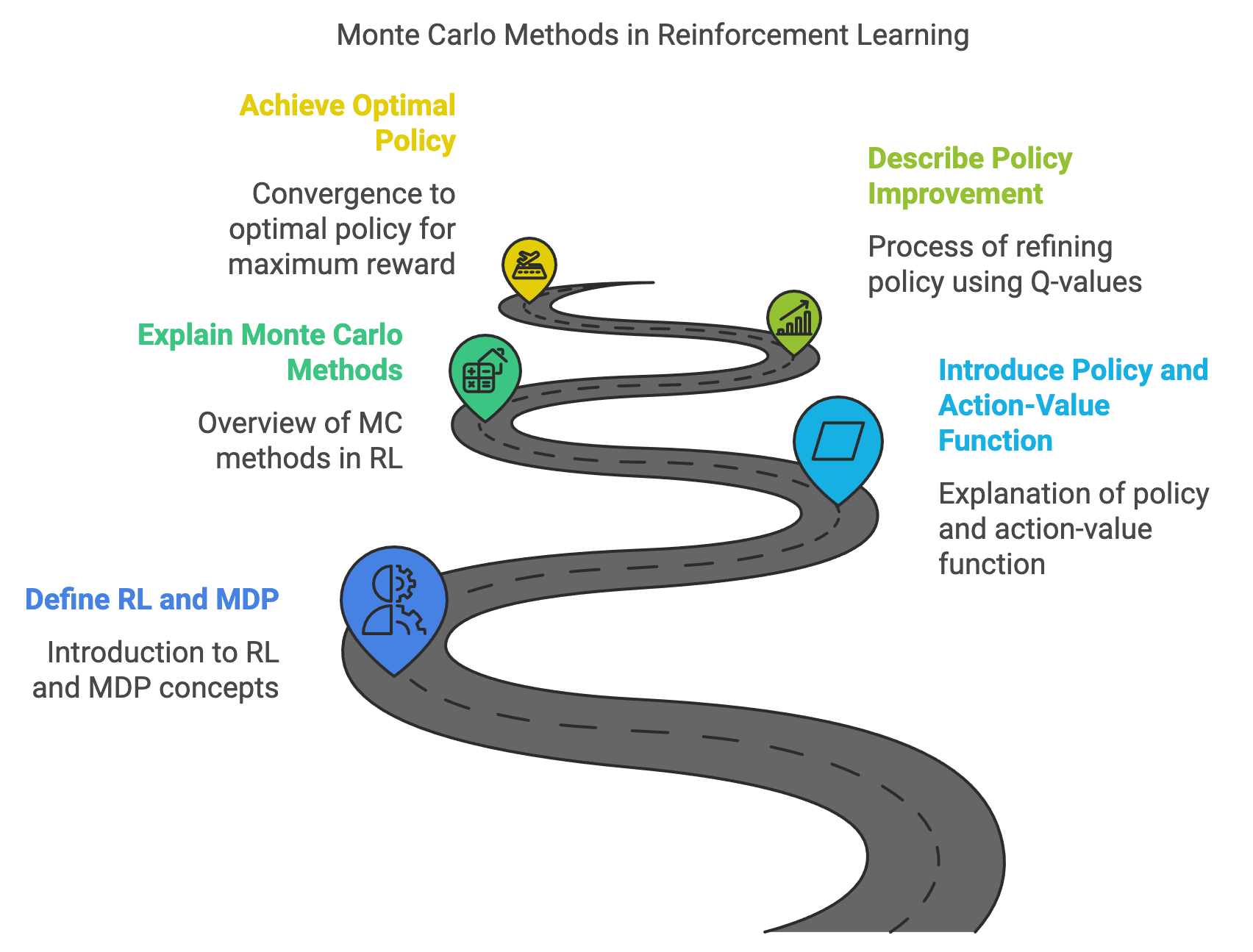

Lets recall that Reinforcement learning (RL) is a subfield of machine learning focused on training agents to make sequences of decisions in environments to maximize cumulative rewards. The agent interacts with an environment modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), where states, actions, rewards, and transitions define the dynamics. In this setting, a policy $\pi(a|s)$ represents the probability of taking action aaa in state $s$, and the goal is to find an optimal policy $\pi^*$ that maximizes the expected cumulative reward from any starting state. Central to RL is the concept of the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$, which estimates the expected return from taking an action aaa in a state $s$ and following policy $\pi$ thereafter.

Figure 2: The scopes of Monte Carlo methods in RL.

Monte Carlo (MC) methods are one of the key approaches in RL to estimate action-value functions and improve policies. Unlike temporal difference (TD) methods, which rely on step-by-step updates, MC methods evaluate $Q^\pi(s, a)$ using complete episodes. By simulating episodes that terminate in a goal state, MC methods compute the cumulative reward (or return) for each state-action pair encountered in the episode. These returns are then averaged to produce an estimate of $Q^\pi(s, a)$. This episodic nature allows MC methods to be model-free, meaning they do not require knowledge of the environment’s dynamics, making them well-suited for complex or unknown systems.

Monte Carlo methods are essential in RL for several reasons. First, they allow the agent to evaluate policies without requiring a model of the environment's dynamics, making them highly applicable in real-world scenarios. Second, by focusing on episodic tasks, Monte Carlo methods work well in environments where interactions naturally terminate (e.g., games or navigation problems). Third, they enable the agent to estimate both state-value functions $V^\pi(s)$ and action-value functions $Q^\pi(s, a)$, providing a foundation for policy optimization. For example, in a navigation problem, Monte Carlo methods can estimate the long-term reward (e.g., reaching a goal) associated with each state by averaging the outcomes of multiple paths (episodes) starting from that state.

Monte Carlo methods are designed for episodic tasks, where interactions naturally break into episodes with a clear beginning and end. The return $G_t$ captures the cumulative reward obtained from the current time step until the episode terminates. By aggregating returns over multiple episodes, Monte Carlo methods provide robust estimates of the value function.

Monte Carlo methods can estimate the value of a state using two approaches:

First-Visit Monte Carlo: Estimates the value of a state $s$ by averaging the returns observed in episodes where $s$ is visited for the first time.

Every-Visit Monte Carlo: Estimates the value of $s$ by averaging the returns observed across all visits to $s$ in all episodes.

While both methods converge to the true value function under the law of large numbers, their performance may vary depending on the problem.

The law of large numbers underpins the reliability of Monte Carlo methods. It ensures that as the number of episodes $N$ increases, the Monte Carlo estimate $\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N G_t^{(i)}$ converges to the true expected value $\mathbb{E}[G_t]$. In practice, this means that the accuracy of Monte Carlo estimates improves with more sampled episodes.

The following implementation demonstrates Monte Carlo methods in a simple grid world environment. The code includes generating episodic data, computing first-visit Monte Carlo estimates, and visualizing the results. Experiments with different random sampling strategies highlight their impact on estimation accuracy.

This code simulates an episodic interaction in a grid-world environment using Monte Carlo methods. The GridWorld struct represents a simple environment where an agent starts at the top-left corner and navigates randomly until it reaches a specified goal state. The agent incurs a step penalty for each move and receives no penalty upon reaching the goal. The episode generation leverages randomness to simulate unpredictable movement, mimicking real-world stochastic environments commonly studied in reinforcement learning.

use rand::Rng;

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self) -> Vec<(usize, usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != self.goal_state {

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state.0, state.1, reward));

state = match rng.gen_range(0..4) {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

}

episode.push((state.0, state.1, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episode = grid_world.generate_episode();

println!("Generated Episode: {:?}", episode);

}

The GridWorld struct defines the grid's size and the goal state. The generate_episode method generates a sequence of state transitions (an episode) by randomly choosing actions (up, down, left, or right) until the agent reaches the goal. The rand::Rng trait is used to introduce randomness into action selection, and boundary conditions are handled to prevent the agent from moving outside the grid. Each step records the current state and the associated reward in the episode vector. Upon reaching the goal state, the final step with a reward of 0.0 is added to signify the end of the episode. In main, the code initializes a 4x4 grid world with a goal at (3, 3), generates a random episode, and prints the sequence of states and rewards.

This code implements a Monte Carlo first-visit method to estimate the value function for states in a grid-world environment, coupled with a visualization using the plotters crate. The grid-world simulates an agent starting at the top-left corner and moving randomly through the grid until reaching a predefined goal state. The Monte Carlo method calculates the average discounted return for each state based on its first occurrence in multiple randomly generated episodes, providing a model-free way to estimate the value function. The visualization highlights the computed value function, visually differentiating the goal state from others.

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::HashMap;

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self) -> Vec<(usize, usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != self.goal_state {

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state.0, state.1, reward));

state = match rng.gen_range(0..4) {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

}

episode.push((state.0, state.1, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

fn monte_carlo_first_visit(

episodes: Vec<Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>>,

gamma: f64,

) -> HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> {

let mut returns: HashMap<(usize, usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

let mut value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

for episode in &episodes {

let mut visited_states = HashMap::new();

let mut g = 0.0;

for (_t, &(x, y, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited_states.contains_key(&(x, y)) {

returns.entry((x, y)).or_insert_with(Vec::new).push(g);

visited_states.insert((x, y), true);

}

}

}

for (state, rewards) in returns.iter() {

value_function.insert(*state, rewards.iter().sum::<f64>() / rewards.len() as f64);

}

value_function

}

fn visualize_grid(grid_size: usize, value_function: &HashMap<(usize, usize), f64>, goal_state: (usize, usize)) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("grid_world.png", (600, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let cell_size = 600 / grid_size;

let font = ("sans-serif", 20);

for row in 0..grid_size {

for col in 0..grid_size {

let x0 = (col * cell_size) as i32;

let y0 = (row * cell_size) as i32;

let x1 = ((col + 1) * cell_size) as i32;

let y1 = ((row + 1) * cell_size) as i32;

let state = (row, col);

let value = value_function.get(&state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let color = if state == goal_state {

RED.mix(0.5) // Highlight the goal state

} else {

BLUE.mix(0.5)

};

root.draw(&Rectangle::new([(x0, y0), (x1, y1)], color.filled())).unwrap();

root.draw(&Text::new(

format!("{:.1}", value),

((x0 + x1) / 2, (y0 + y1) / 2),

font.into_font().color(&WHITE),

))

.unwrap();

}

}

root.present().unwrap();

println!("Grid visualization saved as 'grid_world.png'.");

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes: Vec<_> = (0..1000).map(|_| grid_world.generate_episode()).collect();

let gamma = 0.9;

let value_function = monte_carlo_first_visit(episodes, gamma);

println!("Value Function: {:?}", value_function);

visualize_grid(grid_world.size, &value_function, grid_world.goal_state);

}

The GridWorld struct defines the environment's size and goal state, with the generate_episode method producing episodes of random navigation. The Monte Carlo method processes 1,000 episodes, computing the discounted return ($G$) for each state in reverse order and averaging these returns for first-visit states. The visualize_grid function uses the plotters crate to create a visual representation of the grid, where each cell is color-coded (red for the goal state, blue for others) and labeled with the state's estimated value. The program outputs a PNG file, grid_world.png, displaying the value function, offering both numerical and graphical insights into the agent's learned environment.

This code explores the effect of different sampling strategies on estimation accuracy.

fn visualize_grid(

grid_size: usize,

value_function: &HashMap<(usize, usize), f64>,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

filename: &str,

) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (600, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let cell_size = 600 / grid_size;

let font = ("sans-serif", 20);

for row in 0..grid_size {

for col in 0..grid_size {

let x0 = (col * cell_size) as i32;

let y0 = (row * cell_size) as i32;

let x1 = ((col + 1) * cell_size) as i32;

let y1 = ((row + 1) * cell_size) as i32;

let state = (row, col);

let value = value_function.get(&state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let color = if state == goal_state {

RED.mix(0.5) // Highlight the goal state

} else {

BLUE.mix(0.5)

};

root.draw(&Rectangle::new([(x0, y0), (x1, y1)], color.filled())).unwrap();

root.draw(&Text::new(

format!("{:.1}", value),

((x0 + x1) / 2, (y0 + y1) / 2),

font.into_font().color(&WHITE),

))

.unwrap();

}

}

root.present().unwrap();

println!("Grid visualization saved as '{}'", filename);

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let sample_sizes = vec![100, 500, 1000];

let gamma = 0.9;

for &n in &sample_sizes {

let episodes: Vec<_> = (0..n).map(|_| grid_world.generate_episode()).collect();

let value_function = monte_carlo_first_visit(episodes, gamma);

println!("Sample Size: {}, Value Function: {:?}", n, value_function);

// Properly pass the filename to visualize_grid

let filename = format!("grid_world_sample_{}.png", n);

visualize_grid(grid_world.size, &value_function, grid_world.goal_state, &filename);

}

}

The modified main function introduces an experiment to study the effect of varying sample sizes on the accuracy of Monte Carlo value function estimation. It iterates over a predefined set of sample sizes (100, 500, and 1000), generating a corresponding number of episodes for each sample size and computing the value function using the Monte Carlo first-visit method. Additionally, the function visualizes the value function for each sample size and saves the results as PNG files with filenames reflecting the sample size (e.g., grid_world_sample_100.png). This change allows both numerical and graphical analysis of how larger sample sizes improve the stability and accuracy of the value function estimates, highlighting the relationship between the quantity of data and the quality of Monte Carlo-based learning.

By integrating theoretical principles with practical implementations in Rust, this section provides a comprehensive foundation for understanding and applying Monte Carlo methods in reinforcement learning. The examples and experiments highlight the flexibility and power of Monte Carlo methods in real-world scenarios.

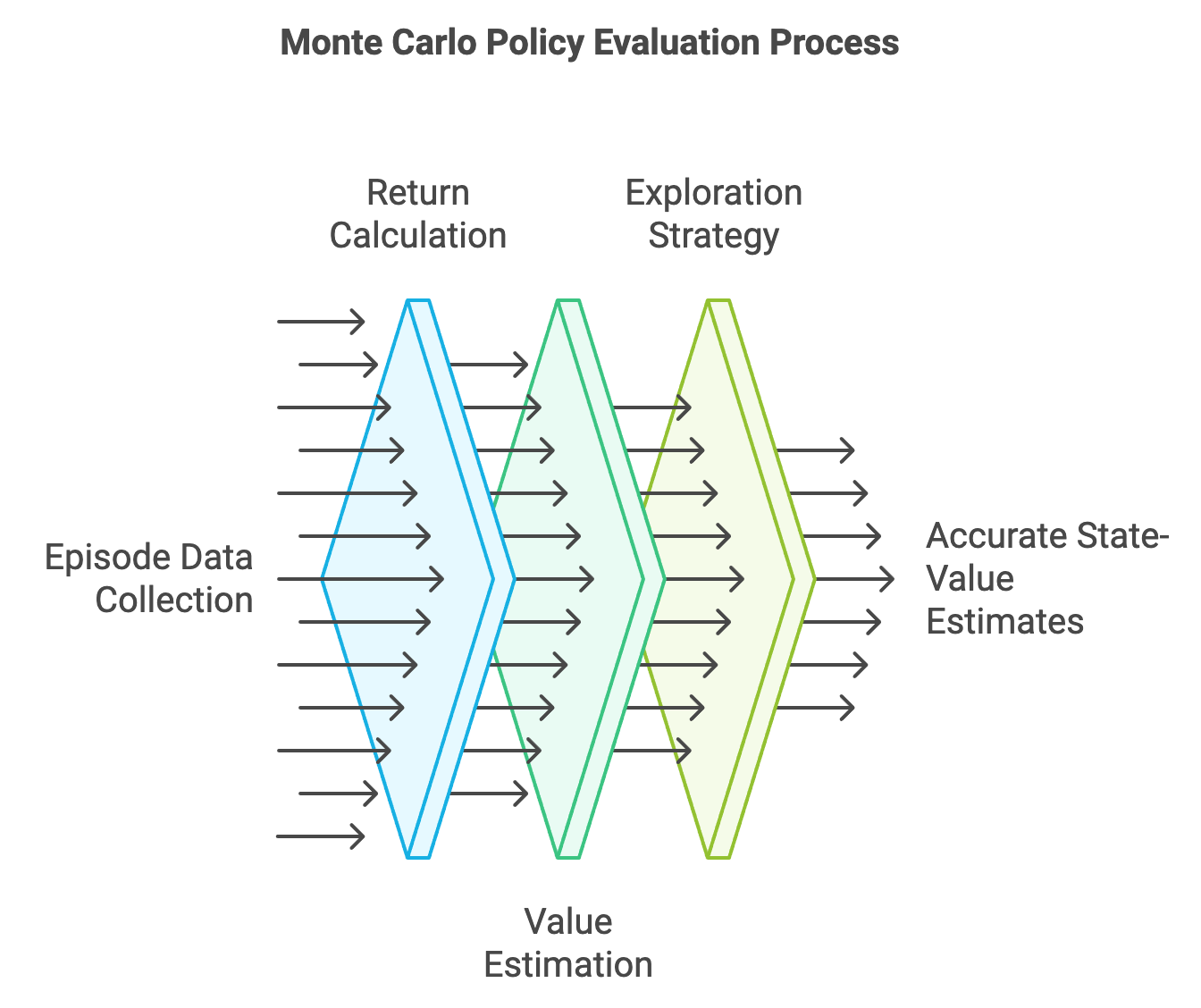

5.2. Monte Carlo Policy Evaluation

Monte Carlo (MC) methods provide a robust way to evaluate policies by estimating the value function based on sampled episodes. Policy evaluation involves computing the state-value function $V^\pi(s)$, which represents the expected cumulative reward when starting from state $s$ and following policy $\pi$. Unlike dynamic programming, which requires a model of the environment, Monte Carlo methods work directly with experience, making them model-free and particularly useful in complex, real-world scenarios.

Mathematically, Monte Carlo policy evaluation estimates $V^\pi(s)$ by averaging the returns $G_t$ observed across multiple episodes:

$$ V^\pi(s) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $G_t^{(i)}$ is the return observed in the $i$-th episode starting from state $s$, and $N$ is the total number of episodes where $s$ was visited. These estimates are unbiased and converge to the true value as $N$ increases, thanks to the law of large numbers.

Figure 3: The process of policy evaluation in Monte Carlo method.

Monte Carlo methods are particularly effective for episodic tasks, where interactions naturally terminate. For instance, in a card game, each round represents an episode with a clear beginning and end. By observing the cumulative rewards at the end of each episode, the agent refines its estimates of state values.

To obtain accurate value estimates for all states, the policy $\pi$ must ensure that every state is visited sufficiently often. This is known as exploration. Without adequate exploration, certain states may be underrepresented or entirely ignored, leading to biased and incomplete value estimates. Strategies such as epsilon-greedy exploration, where the agent occasionally takes random actions, help ensure comprehensive state coverage.

An intuitive analogy is polling for an election. To get an unbiased estimate of voter preferences (state values), the polling strategy must sample from all demographic groups (states). Over-sampling one group while neglecting others leads to inaccurate results.

Monte Carlo methods can be categorized into on-policy and off-policy approaches based on how data is collected and used:

On-Policy Methods: Evaluate the value function of the policy $\pi$ using data generated by $\pi$ itself. For example, an epsilon-greedy policy generates data for its own evaluation. These methods are straightforward but require $\pi$ to balance exploration and exploitation.

Off-Policy Methods: Evaluate a target policy $\pi_{\text{target}}$ using data generated by a different behavior policy $\pi_{\text{behavior}}$. This requires correcting for the difference in distribution using importance sampling, which reweights returns to account for the mismatch:

$$ V^{\pi_{\text{target}}}(s) \approx \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N \rho^{(i)} G_t^{(i)}}{\sum_{i=1}^N \rho^{(i)}}, $$

where $\rho^{(i)} = \prod_{t=1}^{T} \frac{\pi_{\text{target}}(a_t | s_t)}{\pi_{\text{behavior}}(a_t | s_t)}$ is the importance sampling ratio.

Off-policy methods are more flexible but can suffer from high variance, especially when the behavior and target policies differ significantly.

The provided Rust code implements a simple reinforcement learning framework featuring a grid-world environment. It defines a GridWorld struct to model the environment, where an agent starts from a designated state (0, 0) and attempts to reach a goal state (3, 3) while navigating based on an ϵ\\epsilonϵ-greedy policy. The generate_episode method simulates agent interactions in the grid-world environment, creating episodes that store states, actions, and rewards. Additionally, the code includes a function, monte_carlo_first_visit, to perform first-visit Monte Carlo policy evaluation, calculating the value function for each state based on simulated episodes.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define a grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[usize], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start state

while state != self.goal_state {

let action_index = state.0 * self.size + state.1;

if action_index >= policy.len() {

panic!(

"Index out of bounds: state {:?} translates to index {} but policy length is {}",

state, action_index, policy.len()

);

}

// \(\epsilon\)-greedy action selection

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore: random action

} else {

policy[action_index] // Exploit: follow the policy

};

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state, action, reward));

// Determine the next state based on the action

state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => panic!("Invalid action: {}", action),

};

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

// First-visit Monte Carlo policy evaluation

fn monte_carlo_first_visit(

episodes: Vec<Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)>>,

gamma: f64,

) -> HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> {

let mut returns: HashMap<(usize, usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

let mut value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

for episode in &episodes {

let mut visited_states = HashMap::new();

let mut g = 0.0;

for (_t, &((x, y), _, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited_states.contains_key(&(x, y)) {

returns.entry((x, y)).or_insert_with(Vec::new).push(g);

visited_states.insert((x, y), true);

}

}

}

for (state, rewards) in returns.iter() {

value_function.insert(*state, rewards.iter().sum::<f64>() / rewards.len() as f64);

}

value_function

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let policy = vec![0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3]; // A simple policy

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate

let episodes: Vec<_> = (0..1000)

.map(|_| grid_world.generate_episode(&policy, epsilon))

.collect();

let gamma = 0.9;

let value_function = monte_carlo_first_visit(episodes, gamma);

println!("Value Function: {:?}", value_function);

}

The GridWorld struct models the environment as a grid of a specified size with a designated goal state. The generate_episode method uses an $\epsilon$-greedy policy to decide the agent's actions, balancing exploration (random moves) and exploitation (policy-driven moves). Each episode records the state, action, and reward for each step until the goal state is reached. The monte_carlo_first_visit function then evaluates the policy by processing multiple episodes: it computes the cumulative discounted reward $G_t$ for each state, ensuring rewards are only added the first time a state is visited in an episode. Finally, it averages these rewards over all episodes to estimate the state value function. The main function ties everything together, creating a 4x4 grid-world, simulating 1,000 episodes, and calculating the value function with a discount factor ($\gamma = 0.9$). The results are printed as a mapping of state coordinates to their respective value estimates.

This updated implementation builds upon the previous code by introducing off-policy Monte Carlo evaluation with importance sampling, which allows evaluating a target policy using episodes generated from a separate behavior policy. Unlike the earlier code, which evaluated a policy based on episodes it directly followed, this version decouples the evaluation from the data collection process. This flexibility is useful in scenarios where the agent's behavior is driven by one policy (e.g., exploratory behavior) while another policy is being evaluated or optimized.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define a grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[usize], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start state

while state != self.goal_state {

let action_index = state.0 * self.size + state.1;

if action_index >= policy.len() {

panic!(

"Index out of bounds: state {:?} translates to index {} but policy length is {}",

state, action_index, policy.len()

);

}

// \(\epsilon\)-greedy action selection

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore: random action

} else {

policy[action_index] // Exploit: follow the policy

};

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state, action, reward));

// Determine the next state based on the action

state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => panic!("Invalid action: {}", action),

};

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

// Off-policy Monte Carlo evaluation using importance sampling

fn monte_carlo_off_policy(

episodes: Vec<Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)>>,

target_policy: &[usize],

behavior_policy: &[usize],

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut weights: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

for episode in &episodes {

let mut g = 0.0;

let mut rho = 1.0;

for &((x, y), action, reward) in episode.iter().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

let target_action = target_policy[x * 4 + y];

let behavior_action_prob = if action == behavior_policy[x * 4 + y] {

1.0 - epsilon + epsilon / 4.0

} else {

epsilon / 4.0

};

// Update rho

rho *= if target_action == action {

1.0 / behavior_action_prob

} else {

0.0

};

if rho == 0.0 {

break;

}

let entry = value_function.entry((x, y)).or_insert(0.0);

let weight = weights.entry((x, y)).or_insert(0.0);

*entry += rho * g;

*weight += rho;

}

}

for (state, value) in value_function.iter_mut() {

if let Some(&weight) = weights.get(state) {

if weight > 0.0 {

*value /= weight;

}

}

}

value_function

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let behavior_policy = vec![0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3, 0, 1, 2, 3]; // A simple behavior policy

let target_policy = vec![0, 0, 2, 2, 0, 0, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, 3, 1, 1, 3, 3]; // A different target policy

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate for behavior policy

let episodes: Vec<_> = (0..1000)

.map(|_| grid_world.generate_episode(&behavior_policy, epsilon))

.collect();

let gamma = 0.9;

let value_function = monte_carlo_off_policy(episodes, &target_policy, &behavior_policy, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Value Function: {:?}", value_function);

}

This code evaluates the target policy using episodes generated from a separate behavior policy via off-policy Monte Carlo evaluation with importance sampling. The generate_episode method creates episodes by simulating an agent's interaction in a grid-world environment, following an $\epsilon$-greedy behavior policy that balances exploration and exploitation. The monte_carlo_off_policy function iterates through these episodes in reverse order, calculating cumulative rewards ($G_t$) and adjusting them by the importance sampling ratio ($\rho$), which measures alignment between the target and behavior policies. The state values are then updated proportionally to these weighted rewards. Finally, the value function for the target policy is normalized using cumulative weights, resulting in a mapping of grid states to their estimated value under the target policy.

By integrating theoretical principles and practical Rust implementations, this section equips readers with a deep understanding of Monte Carlo policy evaluation methods. The examples showcase the flexibility of on-policy and off-policy approaches, highlighting their strengths and challenges in reinforcement learning tasks.

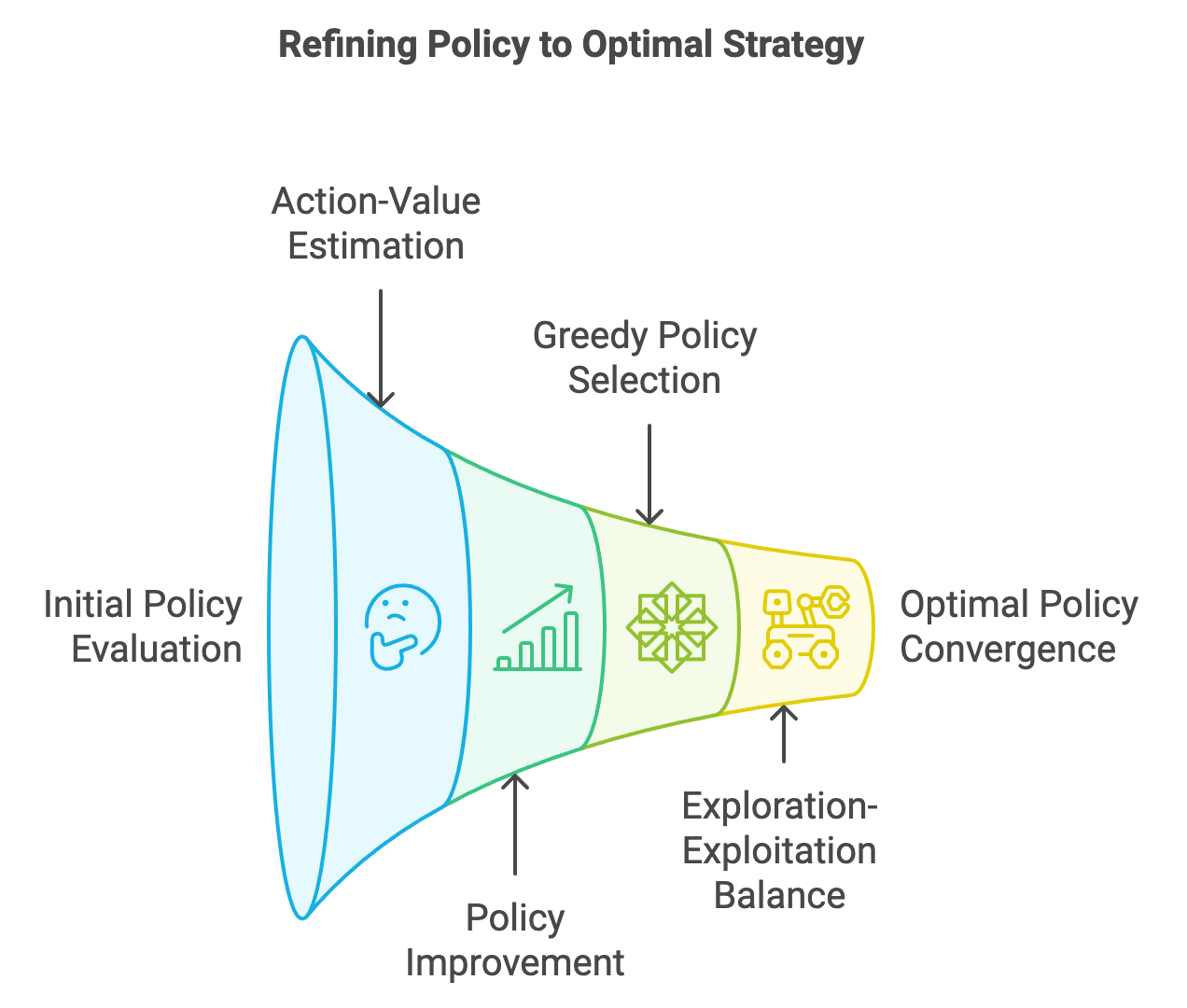

5.3. Monte Carlo Policy Improvement

Policy improvement is the process of refining a policy $\pi$ using the estimates of $Q^\pi(s, a)$. It builds upon the principle of policy evaluation, where $Q^\pi(s, a)$ is calculated for a given policy, and updates the policy to prioritize actions with higher estimated values. This is achieved using the greedy policy concept, which selects actions that maximize $Q^\pi(s, a)$ for each state. The interplay of policy evaluation and policy improvement forms the basis of generalized policy iteration (GPI), a cornerstone of RL. Monte Carlo policy improvement leverages these ideas to refine the policy iteratively, aiming to converge to the optimal policy $\pi^*$, which maximizes the expected cumulative reward across all states.

Monte Carlo (MC) policy improvement builds upon the foundation of policy evaluation, using the estimated action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ to iteratively refine a policy. The goal is to converge to the optimal policy $\pi^*$, which maximizes the expected cumulative reward for all states. Monte Carlo methods achieve this by leveraging the greedy policy concept: at each step, the policy is updated to choose actions that maximize $Q^\pi(s, a)$.

Mathematically, the improved policy is defined as:

$$ \pi'(s) = \arg\max_{a \in \mathcal{A}} Q^\pi(s, a), $$

where $Q^\pi(s, a)$ is the action-value function representing the expected return for taking action aaa in state $s$ and following $\pi$ thereafter. By alternating between policy evaluation and improvement, Monte Carlo methods iteratively refine the policy until convergence to $\pi^*$.

Figure 4: Process to get optimal strategy by refining policy.

An intuitive analogy for policy improvement is playing a strategy game. Initially, you might make random moves (exploration) to understand the game mechanics. Over time, as you learn which moves lead to better outcomes, you focus on making those moves (exploitation), eventually converging to an optimal strategy.

The greedy policy is central to Monte Carlo policy improvement. It selects actions that maximize the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$, which Monte Carlo methods estimate from sampled episodes:

$$ Q^\pi(s, a) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $G_t^{(i)}$ is the return observed in the $i$-th episode after taking action $a$ in state $s$. This process relies on the law of large numbers, ensuring convergence of $Q^\pi(s, a)$ to its true value as $N \to \infty$.

However, purely greedy policies can fall into the trap of exploitation too early, ignoring unexplored actions that may lead to better outcomes. To address this, Monte Carlo methods often use epsilon-greedy policies, which balance exploration and exploitation by occasionally selecting random actions with probability $\epsilon$:

$$ \pi_\epsilon(s, a) = \begin{cases} 1 - \epsilon + \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}|}, & \text{if } a = \arg\max_{a' \in \mathcal{A}} Q^\pi(s, a'), \\ \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}|}, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} $$

The exploration-exploitation trade-off ensures sufficient exploration of the state-action space, facilitating convergence to the optimal policy.

Monte Carlo policy improvement is guaranteed to converge to the optimal policy π∗\\pi^\*π∗ under two conditions:

Sufficient Exploration: The policy must explore all state-action pairs infinitely often. This is typically achieved using epsilon-greedy exploration.

Accurate Evaluation: The action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ must be estimated with sufficient precision through repeated sampling.

The alternating process of evaluation and improvement ensures that each iteration brings the policy closer to optimality. Over time, the updates to $Q^\pi(s, a)$ and $\pi$ diminish, leading to convergence.

The following implementation demonstrates Monte Carlo policy improvement in a grid world environment. The agent starts with a random policy and iteratively refines it using the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$. The code includes epsilon-greedy exploration and experiments with different epsilon values to analyze the trade-off between exploration and exploitation.

This Rust program demonstrates Monte Carlo policy improvement in a simple grid-world environment. The GridWorld struct defines the environment, including the grid's size and the goal state. The generate_episode method simulates an episode by navigating the agent through the grid using an epsilon-greedy policy. The agent can take one of four actions (up, down, left, right), and each step incurs a penalty of -1 until the goal is reached.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[f64], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != self.goal_state {

let state_index = state.0 * self.size + state.1;

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore randomly

} else {

let start = state_index * 4;

let end = start + 4;

policy[start..end]

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap_or(0)

};

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state, action, reward));

// More robust state transition with bounds checking

state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => state, // Fallback to current state

};

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

// Monte Carlo policy improvement

fn monte_carlo_policy_improvement(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

epsilon: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>, Vec<f64>) {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut returns: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

// Flattened policy with 4 probabilities for each state

let mut policy = vec![0.25; grid_world.size * grid_world.size * 4];

for _ in 0..episodes {

let episode = grid_world.generate_episode(&policy, epsilon);

let mut g = 0.0;

let mut visited = HashMap::new();

for (_, &((x, y), action, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited.contains_key(&(x, y, action)) {

returns

.entry(((x, y), action))

.or_insert_with(Vec::new)

.push(g);

visited.insert((x, y, action), true);

let q = returns[&((x, y), action)].iter().sum::<f64>()

/ returns[&((x, y), action)].len() as f64;

q_values.insert(((x, y), action), q);

let state_index = x * grid_world.size + y;

let max_action = (0..4)

.max_by(|a, b| {

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *a))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY)

.partial_cmp(

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *b))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY),

)

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap();

// Update the probabilities in the flattened policy

for i in 0..4 {

policy[state_index * 4 + i] = if i == max_action {

1.0 - epsilon + (epsilon / 4.0)

} else {

epsilon / 4.0

};

}

}

}

}

(q_values, policy)

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let (q_values, policy) = monte_carlo_policy_improvement(&grid_world, episodes, epsilon, gamma);

println!("Final Q-Values: {:?}", q_values);

println!("Final Policy: {:?}", policy);

}

The monte_carlo_policy_improvement function trains the policy over multiple episodes by computing action-value estimates (Q-values) using the discounted cumulative rewards observed during the episodes. These Q-values are updated iteratively, and the policy is refined to favor actions with higher Q-values, incorporating some randomness based on the epsilon parameter to encourage exploration. The main function initializes a 4x4 grid-world environment with a goal at (3, 3), trains the policy using Monte Carlo updates, and prints the final Q-values and policy.

The following revised Rust code implements a Monte Carlo reinforcement learning algorithm for policy improvement in a grid-world environment. The program uses a stochastic exploration strategy (epsilon-greedy) and evaluates the resulting policies based on their success rates and average steps to reach the goal.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[f64], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0);

let mut steps = 0;

while state != self.goal_state {

steps += 1;

if steps > self.size * self.size * 2 { // Prevent infinite loops

break;

}

let state_index = state.0 * self.size + state.1;

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore randomly

} else {

let start = state_index * 4;

let end = start + 4;

policy[start..end]

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap_or(0)

};

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state, action, reward));

// More robust state transition with bounds checking

state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => state, // Fallback to current state

};

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

// New method to evaluate policy

fn evaluate_policy(&self, policy: &[f64], episodes: usize) -> (f64, f64) {

let mut total_steps = 0;

let mut success_count = 0;

for _ in 0..episodes {

let episode = self.generate_episode(policy, 0.0); // No exploration during evaluation

if episode.last().map(|&((x, y), _, _)| (x, y)) == Some(self.goal_state) {

success_count += 1;

total_steps += episode.len();

}

}

let success_rate = success_count as f64 / episodes as f64;

let avg_steps = if success_count > 0 {

total_steps as f64 / success_count as f64

} else {

f64::INFINITY

};

(success_rate, avg_steps)

}

}

// Monte Carlo policy improvement (unchanged from previous version)

fn monte_carlo_policy_improvement(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

epsilon: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>, Vec<f64>) {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut returns: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

// Flattened policy with 4 probabilities for each state

let mut policy = vec![0.25; grid_world.size * grid_world.size * 4];

for _ in 0..episodes {

let episode = grid_world.generate_episode(&policy, epsilon);

let mut g = 0.0;

let mut visited = HashMap::new();

for (_, &((x, y), action, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited.contains_key(&(x, y, action)) {

returns

.entry(((x, y), action))

.or_insert_with(Vec::new)

.push(g);

visited.insert((x, y, action), true);

let q = returns[&((x, y), action)].iter().sum::<f64>()

/ returns[&((x, y), action)].len() as f64;

q_values.insert(((x, y), action), q);

let state_index = x * grid_world.size + y;

let max_action = (0..4)

.max_by(|a, b| {

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *a))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY)

.partial_cmp(

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *b))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY),

)

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap();

// Update the probabilities in the flattened policy

for i in 0..4 {

policy[state_index * 4 + i] = if i == max_action {

1.0 - epsilon + (epsilon / 4.0)

} else {

epsilon / 4.0

};

}

}

}

}

(q_values, policy)

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

// Learning parameters

let training_episodes = 1000;

let evaluation_episodes = 100;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilon_values = vec![0.0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5];

println!("Epsilon | Training Episodes | Success Rate | Avg Steps to Goal");

println!("--------|------------------|--------------|------------------");

for &epsilon in &epsilon_values {

// Train the policy

let (_, policy) = monte_carlo_policy_improvement(

&grid_world,

training_episodes,

epsilon,

gamma

);

// Evaluate the policy

let (success_rate, avg_steps) = grid_world.evaluate_policy(&policy, evaluation_episodes);

println!(

"{:.2} | {:<16} | {:.2}% | {:.2}",

epsilon,

training_episodes,

success_rate * 100.0,

avg_steps

);

}

}

The monte_carlo_policy_improvement function trains a policy using Monte Carlo methods, where the agent iteratively explores and updates its action-value estimates (Q-values) based on observed returns. It refines the policy toward optimal actions using an epsilon-greedy approach. After training, the policy is evaluated using the evaluate_policy method, which measures success rate and average steps over a set number of episodes. The main function trains and evaluates policies across various epsilon values, presenting the relationship between exploration, success, and efficiency in solving the grid-world task.

By combining theoretical insights with practical Rust implementations, this section equips readers with a comprehensive understanding of Monte Carlo policy improvement, emphasizing its role in achieving optimal decision-making in reinforcement learning.

5.4. Monte Carlo Control

Traditional methods like dynamic programming (DP) rely on access to a complete model of the environment's dynamics, including state transitions and reward probabilities. However, in many real-world problems, these dynamics are unknown or too complex to model explicitly. This limitation has led to the development of model-free methods, such as Monte Carlo (MC) approaches, which estimate $Q^\pi(s, a)$ based on sampled trajectories or episodes of agent-environment interactions. Unlike DP methods, MC techniques evaluate policies by generating complete episodes and computing returns, requiring no prior knowledge of transition probabilities. This episodic nature makes Monte Carlo methods particularly effective for problems where the environment is complex, partially observable, or difficult to model explicitly.

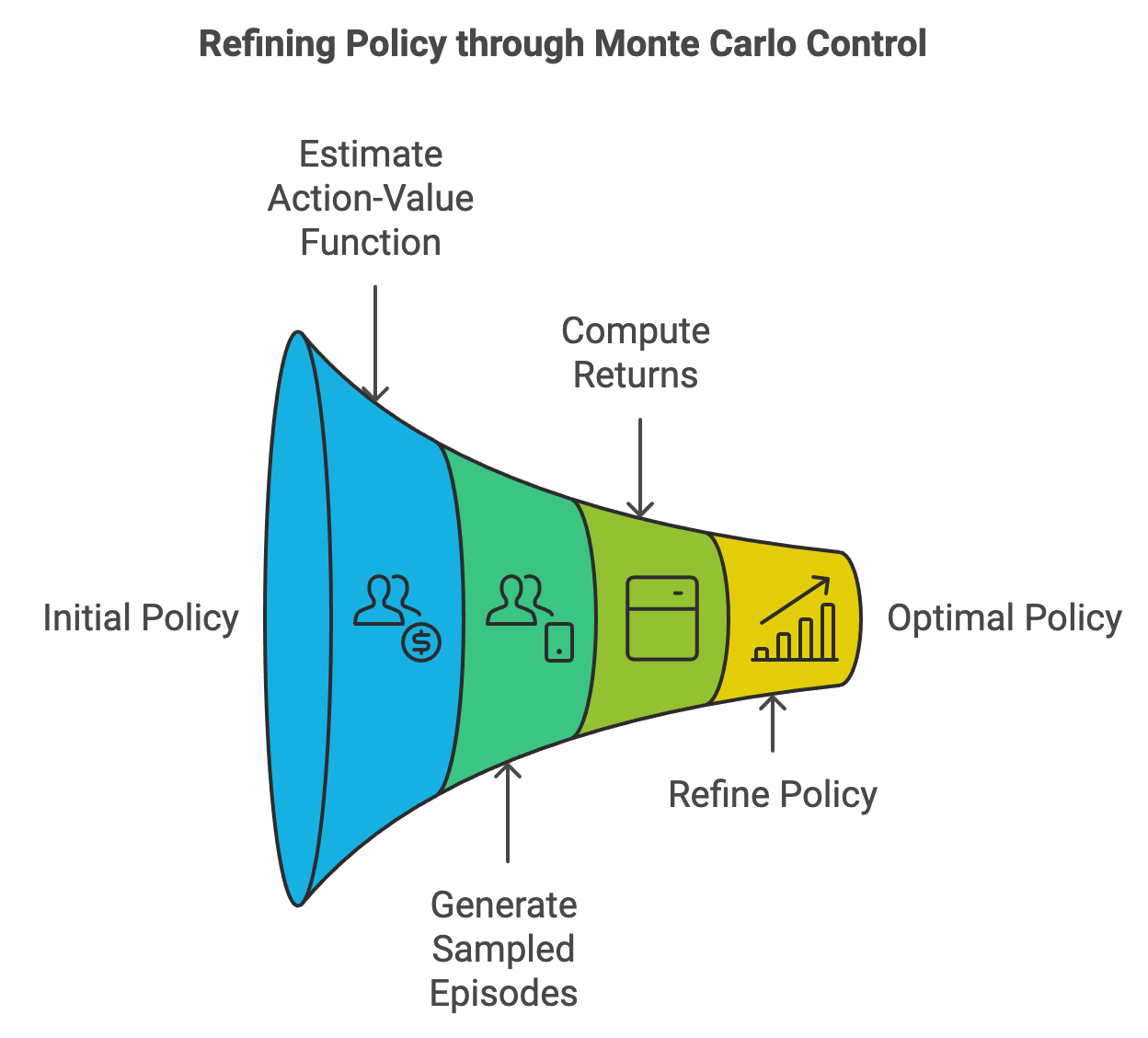

Figure 5: Scopes of refining policy using Monte Carlo control method.

Monte Carlo control is a powerful framework in reinforcement learning that combines policy evaluation and policy improvement to determine the optimal policy $\pi^*$. By repeatedly alternating between estimating the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ for a given policy $\pi$ and refining the policy to maximize expected returns, Monte Carlo control gradually converges to the optimal policy. Unlike dynamic programming methods, Monte Carlo control does not require a model of the environment's dynamics, making it a model-free approach.

At the heart of Monte Carlo control is the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$, which estimates the expected cumulative reward when taking action $a$ in state $s$ and following $\pi$ thereafter. Using sampled episodes, Monte Carlo methods approximate $Q^\pi(s, a)$ as:

$$ Q^\pi(s, a) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $G_t^{(i)}$ is the return observed from the $i$-th episode, and $N$ is the total number of visits to the state-action pair $(s, a)$. The improved policy is then derived as the greedy policy with respect to $Q^\pi(s, a)$:

$$ \pi'(s) = \arg\max_{a \in \mathcal{A}} Q^\pi(s, a). $$

An analogy for Monte Carlo control is playing a board game where you iteratively refine your strategy by learning which moves (actions) in different game scenarios (states) lead to the highest chance of winning (optimal policy).

To ensure the convergence of Monte Carlo control to the optimal policy, it is essential to guarantee sufficient exploration of the state-action space. Without exploration, the algorithm may overlook promising actions, leading to suboptimal policies. Two key techniques address this challenge:

Exploring Starts: This technique initializes episodes from randomly chosen state-action pairs, ensuring that all pairs have an opportunity to be explored. Exploring starts are conceptually simple but may be impractical in some real-world scenarios where starting states and actions are constrained.

Epsilon-Soft Policies: In epsilon-soft policies, each action aaa in state sss has a non-zero probability of being selected, even if it is not currently optimal:

$$ \pi_\epsilon(s, a) = \begin{cases} 1 - \epsilon + \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}|}, & \text{if } a = \arg\max_{a' \in \mathcal{A}} Q^\pi(s, a'), \\ \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}|}, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} $$

This ensures that the agent occasionally explores non-optimal actions, gathering data to improve its estimates of $Q^\pi(s, a)$.

Epsilon-soft policies are analogous to trying new dishes at a restaurant. While you may usually order your favorite dish, occasionally trying others ensures you don’t miss out on discovering a better option.

Monte Carlo control converges to the optimal policy $\pi^*$ under two key conditions:

Comprehensive Exploration: The state-action space must be explored sufficiently, either through exploring starts or epsilon-soft policies.

Accurate Evaluation: The action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ must be estimated with sufficient precision via repeated sampling.

These conditions ensure that each iteration of policy improvement leads to a strictly better or equivalent policy, ultimately converging to the optimal policy.

The following implementation demonstrates Monte Carlo control in a grid world environment. The agent starts with an epsilon-soft policy and iteratively refines it using the action-value function Qπ(s,a)Q^\\pi(s, a)Qπ(s,a). The implementation includes mechanisms for exploration and experiments with different epsilon values to analyze their impact on performance.

The provided Rust program implements Monte Carlo control with epsilon-soft policies in a grid-world environment. The GridWorld struct defines a 2D grid where an agent navigates from a starting position to a goal state. Using reinforcement learning, the program trains an agent to maximize rewards by iteratively improving its policy based on action-value (Q-value) estimates. The agent follows an epsilon-greedy strategy, which balances exploration (random actions) and exploitation (choosing optimal actions based on current knowledge).

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[Vec<f64>], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != self.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore randomly

} else {

policy[state.0 * self.size + state.1]

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap_or(0)

};

let reward = -1.0; // Step penalty

episode.push((state, action, reward));

state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => state, // Fallback to current state

};

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

// Monte Carlo control with epsilon-soft policies

fn monte_carlo_control(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

epsilon: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>, Vec<Vec<f64>>) {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut returns: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

let mut policy = vec![vec![0.25; 4]; grid_world.size * grid_world.size]; // Epsilon-soft policy

for _ in 0..episodes {

let episode = grid_world.generate_episode(&policy, epsilon);

let mut g = 0.0;

let mut visited = HashMap::new();

for (_, &((x, y), action, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited.contains_key(&(x, y, action)) {

returns

.entry(((x, y), action))

.or_insert_with(Vec::new)

.push(g);

visited.insert((x, y, action), true);

let q = returns[&((x, y), action)].iter().sum::<f64>()

/ returns[&((x, y), action)].len() as f64;

q_values.insert(((x, y), action), q);

policy[x * grid_world.size + y] = {

let mut probs = vec![epsilon / 4.0; 4];

let max_action = (0..4)

.max_by(|a, b| {

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *a))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY)

.partial_cmp(

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *b))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY),

)

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap();

probs[max_action] += 1.0 - epsilon;

probs

};

}

}

}

(q_values, policy)

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let (q_values, policy) = monte_carlo_control(&grid_world, episodes, epsilon, gamma);

println!("Final Q-Values: {:?}", q_values);

println!("Final Policy: {:?}", policy);

}

The program begins with the GridWorld environment, where episodes are generated using the generate_episode method. This method simulates agent navigation based on the provided policy and epsilon value, adding step penalties to incentivize efficient paths. The monte_carlo_control function iteratively trains the policy by evaluating the returns (discounted cumulative rewards) for state-action pairs observed in each episode. Action-value estimates are updated based on these returns, and the policy is refined to favor actions with the highest Q-values while maintaining some exploration. The main function initializes the grid-world environment, trains the agent over 1,000 episodes, and prints the final Q-values and policy, which represent the agent's learned optimal behavior.

The improved code introduces a Q-learning implementation alongside Monte Carlo control, enabling a comparison of these two reinforcement learning algorithms. Q-learning operates step-by-step during each episode, updating Q-values immediately after every action based on the temporal difference method. This contrasts with Monte Carlo control, which waits until the end of each episode to calculate and update Q-values using cumulative returns. The addition of Q-learning highlights the trade-offs between episodic updates (Monte Carlo) and stepwise updates (Q-learning), offering insights into their relative efficiency and accuracy in solving the grid-world task.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => ((state.0 + 1).min(self.size - 1), state.1), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (state.0, (state.1 + 1).min(self.size - 1)), // Right

_ => state,

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 };

(next_state, reward)

}

fn generate_episode(&self, policy: &[Vec<f64>], epsilon: f64) -> Vec<((usize, usize), usize, f64)> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != self.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore randomly

} else {

policy[state.0 * self.size + state.1]

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap_or(0)

};

let (next_state, reward) = self.step(state, action);

episode.push((state, action, reward));

state = next_state;

}

episode.push((state, 0, 0.0)); // Goal state with no penalty

episode

}

}

// Monte Carlo control with epsilon-soft policies

fn monte_carlo_control(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

epsilon: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>, Vec<Vec<f64>>) {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut returns: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), Vec<f64>> = HashMap::new();

let mut policy = vec![vec![0.25; 4]; grid_world.size * grid_world.size]; // Epsilon-soft policy

for _ in 0..episodes {

let episode = grid_world.generate_episode(&policy, epsilon);

let mut g = 0.0;

let mut visited = HashMap::new();

for (_, &((x, y), action, reward)) in episode.iter().enumerate().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

if !visited.contains_key(&(x, y, action)) {

returns

.entry(((x, y), action))

.or_insert_with(Vec::new)

.push(g);

visited.insert((x, y, action), true);

let q = returns[&((x, y), action)].iter().sum::<f64>()

/ returns[&((x, y), action)].len() as f64;

q_values.insert(((x, y), action), q);

policy[x * grid_world.size + y] = {

let mut probs = vec![epsilon / 4.0; 4];

let max_action = (0..4)

.max_by(|a, b| {

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *a))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY)

.partial_cmp(

q_values

.get(&((x, y), *b))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY),

)

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap();

probs[max_action] += 1.0 - epsilon;

probs

};

}

}

}

(q_values, policy)

}

// Q-Learning implementation

fn q_learning(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Explore randomly

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|a, b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, *a))

.unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, *b)).unwrap_or(&f64::NEG_INFINITY))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0)

};

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let max_next_q = (0..4)

.map(|a| q_values.get(&(next_state, a)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.cloned()

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let current_q = q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let new_q = current_q + alpha * (reward + gamma * max_next_q - current_q);

q_values.insert((state, action), new_q);

state = next_state;

}

}

q_values

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let alpha = 0.1;

// Monte Carlo Control

let (mc_q_values, mc_policy) = monte_carlo_control(&grid_world, episodes, epsilon, gamma);

println!("Monte Carlo Control Q-Values: {:?}", mc_q_values);

println!("Monte Carlo Control Policy: {:?}", mc_policy);

// Q-Learning

let q_learning_q_values = q_learning(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Q-Learning Q-Values: {:?}", q_learning_q_values);

// Comparison

println!("Comparison completed. Evaluate results in terms of convergence speed and accuracy.");

}

The Q-learning implementation updates the Q-values iteratively by computing the temporal difference between the predicted reward (current Q-value) and the observed reward plus the discounted maximum Q-value of the next state. This allows Q-learning to converge faster since it learns incrementally after each step rather than waiting for episode completion. The code first trains a policy using Monte Carlo control and outputs the resulting Q-values and policy. Then, it trains another policy using Q-learning, outputting its Q-values. The results from both methods can be compared to observe how quickly each algorithm converges to an optimal policy and how accurate these policies are in reaching the goal efficiently.

By integrating theoretical foundations and practical implementations, this section equips readers with a comprehensive understanding of Monte Carlo control, emphasizing its strengths and applications in reinforcement learning tasks.

5.5. Challenges and Limitations of Monte Carlo Methods

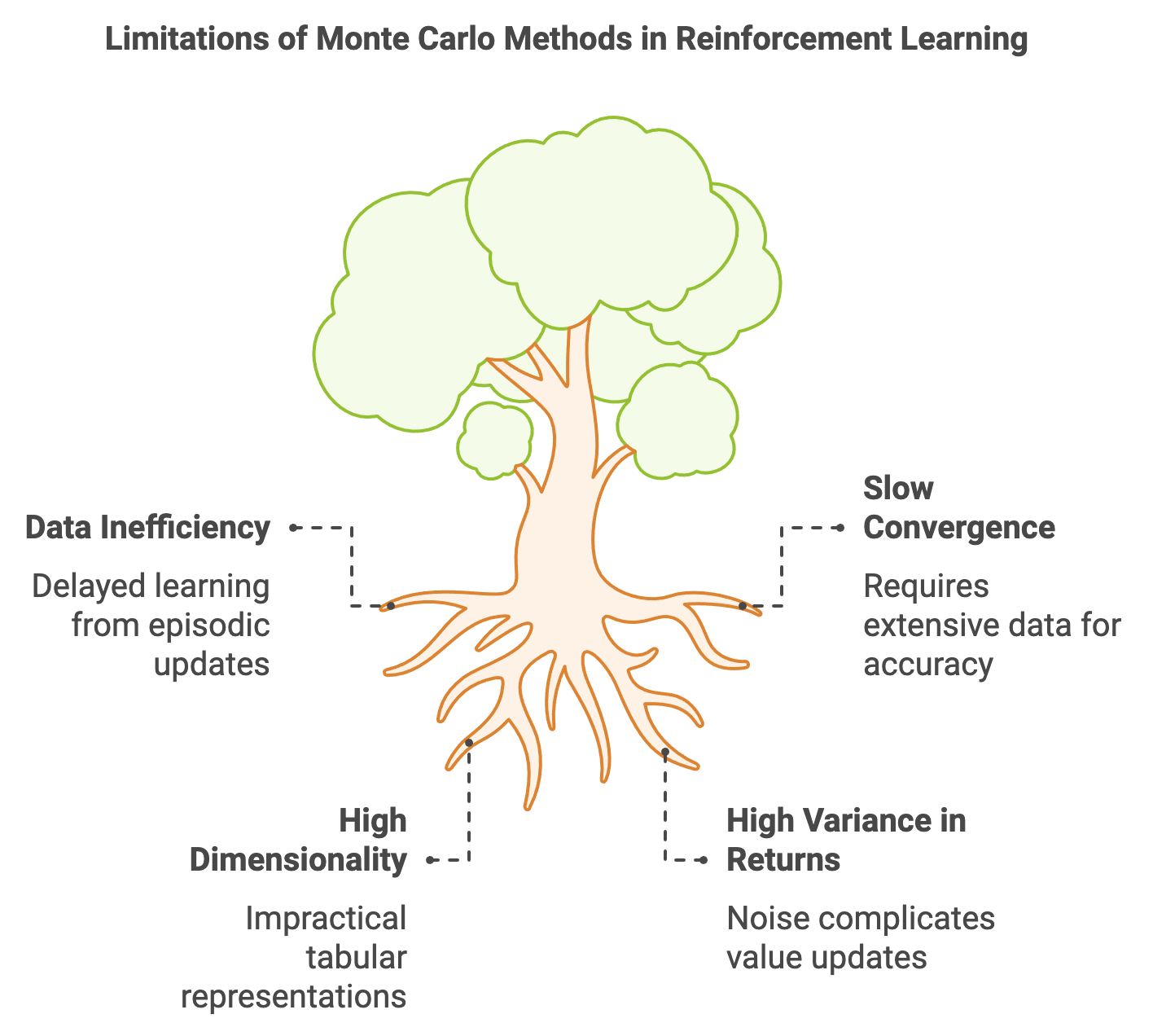

Monte Carlo (MC) methods are a foundational approach in reinforcement learning (RL) that excel in scenarios requiring model-free policy evaluation and improvement. However, they face several inherent challenges that limit their scalability and applicability, particularly in complex real-world environments. One of the primary challenges is data inefficiency, stemming from the episodic nature of MC methods. Since MC relies on complete episodes to calculate the cumulative return (the sum of rewards), it is unsuitable for environments with non-terminating dynamics or extremely long episodes. In such scenarios, the agent cannot update its value estimates until the episode concludes, leading to delayed learning. This episodic dependency constrains the flexibility of MC methods compared to Temporal Difference (TD) learning, which can make incremental updates at every step without waiting for episodes to terminate.

Figure 6: Key challenges of Monte Carlo method implementation for RL.

A related challenge is slow convergence, especially in environments with stochastic or noisy reward structures. MC methods estimate value functions by averaging sampled returns across episodes, and this averaging process requires a large number of samples to produce accurate estimates. In environments with high variability in rewards, the variance in return estimates can further slow down convergence, necessitating extensive data collection and computation. This limitation is exacerbated when agents encounter sparse rewards, where meaningful feedback is infrequent, making it difficult for MC methods to gather enough informative samples efficiently. The dependence on large datasets for convergence makes MC less appealing for applications demanding rapid learning.

Another limitation arises in environments with continuous or high-dimensional state spaces. MC methods traditionally rely on tabular representations to store value estimates, which are impractical when the number of states becomes exceedingly large or when states are continuous. Addressing this requires discretization of continuous spaces or the use of function approximators, such as neural networks, to generalize across similar states. However, discretization can lead to a loss of granularity and introduce bias, while function approximation increases computational complexity and may introduce instability during training. Moreover, MC’s inability to handle high variance in returns efficiently is a significant drawback. Variance in return estimates introduces noise in value function updates, making it challenging to converge to stable solutions. For example, in navigation tasks with inconsistent reward structures, MC methods may require an impractical number of episodes to derive accurate value estimates, highlighting their limitations in dynamic and uncertain environments.

These challenges collectively underscore the limitations of MC methods in modern RL applications. While they remain useful for problems with well-defined episodic structures and manageable state spaces, their applicability diminishes in environments requiring high efficiency, fast convergence, and scalability. This has led to the increased adoption of alternative approaches, such as TD learning and actor-critic methods, which address many of these shortcomings by blending the strengths of MC with incremental learning and function approximation.

Mathematically, the variance in returns is expressed as:

$$ \text{Var}(G_t) = \mathbb{E}[(G_t - \mathbb{E}[G_t])^2], $$

where $G_t$ is the return. High variance increases the spread of sampled returns, necessitating more samples for reliable estimation.

Monte Carlo methods also rely heavily on the assumption of episodic tasks, making them unsuitable for problems like continuous control or infinite-horizon tasks without special modifications. Moreover, they provide no mechanism for bootstrapping—estimating values from other values—unlike TD methods, which update estimates incrementally.

To address these challenges, alternative approaches like Temporal Difference (TD) learning have gained prominence. TD learning combines the advantages of dynamic programming and Monte Carlo methods, using bootstrapping to update value estimates incrementally after every step rather than waiting for an episode to complete. The TD error, a core concept in these methods, is defined as:

$$ \delta_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma V(S_{t+1}) - V(S_t), $$

where $\delta_t$ is the difference between the observed reward and the estimated value. By incorporating this incremental update, TD methods achieve faster convergence and better data efficiency.

Monte Carlo methods trade off immediate learning for unbiased estimates. Unlike TD methods, which are biased but converge faster, MC methods ensure that their estimates are unbiased and accurate given enough data. These methods are particularly effective when the environment is stochastic and the agent lacks a model of the environment's dynamics. However, when tasks involve high variance or continuous states, TD learning or hybrid approaches that combine MC and TD elements are often more effective.

For example, in a game where outcomes depend on unpredictable player interactions, MC methods excel because they work directly from sampled episodes. In contrast, in a robotic control task where feedback is incremental, TD learning is better suited due to its stepwise updates.

The following implementations analyze the limitations of MC methods in terms of data efficiency and convergence speed. They also explore hybrid approaches that combine MC and TD learning, showcasing how such combinations can mitigate MC’s limitations.

This example demonstrates how Monte Carlo methods converge slower in tasks with high variance. The provided code addresses several challenges in RL, such as data inefficiency, high variance in returns, and the difficulty of handling continuous or high-dimensional state spaces. By combining Monte Carlo (MC) estimation, a hybrid approach that integrates MC and Temporal Difference (TD) learning, and function approximation techniques, the program demonstrates methods to overcome these limitations. Each method tackles a specific RL challenge, ranging from handling high-variance environments to making incremental updates for faster convergence and approximating value functions for continuous state spaces.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use rand::Rng;

// Simulate returns with high variance

fn simulate_returns(num_samples: usize, variance: f64) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

(0..num_samples)

.map(|_| rng.gen_range(-variance..variance))

.collect()

}

// Compute Monte Carlo estimate

fn monte_carlo_estimate(returns: Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

let sum: f64 = returns.iter().sum();

sum / returns.len() as f64

}

// Hybrid approach: Monte Carlo + TD learning

fn hybrid_mc_td(

episodes: Vec<Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>>,

gamma: f64,

alpha: f64,

) -> HashMap<usize, f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<usize, f64> = HashMap::new();

for episode in episodes {

let mut g = 0.0;

for &(state, _, reward) in episode.iter().rev() {

g = reward + gamma * g;

let value = value_function.entry(state).or_insert(0.0);

*value += alpha * (g - *value); // Incremental update (TD-like)

}

}

value_function

}

// Function approximation for continuous states

fn approximate_value_function(

states: &Array2<f64>,

rewards: &Array1<f64>,

weights: &Array1<f64>,

learning_rate: f64,

) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut new_weights = weights.to_owned();

for (state, &reward) in states.rows().into_iter().zip(rewards.iter()) {

let prediction: f64 = state.dot(&new_weights);

let error = reward - prediction;

// Perform element-wise multiplication and addition

let gradient = state.to_owned() * (learning_rate * error);

new_weights = &new_weights + &gradient;

}

new_weights

}

fn main() {

// Part 1: Monte Carlo with Variance Simulation

println!("--- Monte Carlo Estimate with Variance Simulation ---");

let num_samples = 1000;

let variances = vec![1.0, 5.0, 10.0];

for &variance in &variances {

let returns = simulate_returns(num_samples, variance);

let estimate = monte_carlo_estimate(returns);

println!(

"Variance: {:.1}, Monte Carlo Estimate: {:.3}",

variance, estimate

);

}

// Part 2: Hybrid Monte Carlo + TD Learning

println!("\n--- Hybrid Monte Carlo + TD Learning ---");

let episodes = vec![

vec![(0, 0, -1.0), (1, 0, -1.0), (2, 0, 0.0)],

vec![(0, 0, -1.0), (1, 0, -1.0), (3, 0, 1.0)],

];

let gamma = 0.9;

let alpha = 0.1;

let value_function = hybrid_mc_td(episodes, gamma, alpha);

println!("Value Function: {:?}", value_function);

// Part 3: Function Approximation for Continuous States

println!("\n--- Function Approximation for Continuous States ---");

let states = Array2::random_using((100, 3), Uniform::new(0.0, 1.0), &mut rand::thread_rng());

let rewards = Array1::random_using(100, Uniform::new(0.0, 1.0), &mut rand::thread_rng());

let weights = Array1::zeros(3);

let learning_rate = 0.1;

let updated_weights = approximate_value_function(&states, &rewards, &weights, learning_rate);

println!("Updated Weights: {:?}", updated_weights);

}

The first part of the program simulates returns with varying levels of variance to highlight the effects of stochastic environments on MC estimation. It generates a series of random returns based on a specified variance and computes the Monte Carlo estimate by averaging these returns. This method illustrates the fundamental principle of MC estimation: using sample averages to approximate expected rewards. However, the simulation also underscores a key challenge—higher variance in returns results in noisier estimates, requiring more samples for reliable approximations. This section provides a practical understanding of the data inefficiency inherent in MC methods, particularly in environments with significant variability.

The second part implements a hybrid approach combining the episodic nature of MC with the stepwise updates of TD learning. Using a sequence of episodes, it calculates the cumulative return ($G_t$) for each state backward through the episode, similar to MC. However, instead of storing and averaging returns, it updates the value function incrementally using TD-like updates with a learning rate ($\alpha$). This hybrid method addresses the slow convergence of traditional MC by leveraging TD’s incremental updates, making learning more efficient. It also demonstrates the flexibility of blending RL techniques to improve adaptability in dynamic environments with finite episodes.

The third part tackles the challenge of continuous or high-dimensional state spaces by implementing function approximation using gradient descent. Here, states are represented as feature vectors, and a linear model approximates the value function. The program iteratively updates the model’s weights based on the error between predicted and actual rewards. This approach generalizes across similar states, reducing the need for explicit tabular representations. Function approximation makes it feasible to handle large or continuous state spaces while addressing the scalability challenges of traditional MC methods. By focusing on weights rather than individual state-action pairs, this method lays the groundwork for extending RL techniques to complex, real-world problems.

In summary, by analyzing the limitations of Monte Carlo methods and exploring alternative and hybrid approaches, this section provides readers with a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in applying Monte Carlo methods to real-world reinforcement learning tasks. The practical Rust implementations highlight key trade-offs and potential solutions for overcoming these limitations.

5.6. Conclusion

Chapter 5 delves into the intricacies of Monte Carlo methods in reinforcement learning, providing both theoretical understanding and practical guidance on their implementation using Rust. By mastering these techniques, readers will be equipped to handle a variety of RL tasks, particularly in environments where model-based approaches are not feasible, and where the flexibility of Monte Carlo methods can be fully leveraged.

5.6.1. Further Learning with GenAI

These prompts are designed to provide a deep exploration of Monte Carlo methods in reinforcement learning, encouraging a comprehensive understanding of the concepts, strategies, and practical implementations using Rust.

Explain the fundamental principles of Monte Carlo methods in reinforcement learning. How do these methods differ from other RL approaches, and what are their key advantages? Implement a basic Monte Carlo method in Rust and discuss its core components.

Discuss the importance of episodic tasks in Monte Carlo methods. Why are these methods particularly suited for tasks where episodes can be clearly defined? Implement an episodic task in Rust and apply Monte Carlo methods to estimate state-value functions.

Explore the concepts of first-visit and every-visit Monte Carlo methods. How do they differ in their approach to estimating value functions, and what are the implications of these differences? Implement both methods in Rust and compare their effectiveness in a simulated environment.

Analyze the role of the law of large numbers in Monte Carlo methods. How does it ensure the convergence of Monte Carlo estimates, and what are the practical implications for reinforcement learning? Implement a Monte Carlo simulation in Rust and observe the convergence behavior over multiple episodes.

Examine the challenges of ensuring sufficient exploration in Monte Carlo methods. How does exploration impact the accuracy of value function estimates, and what strategies can be used to enhance exploration? Implement an exploration strategy in Rust and evaluate its impact on Monte Carlo policy evaluation.

Discuss the differences between on-policy and off-policy Monte Carlo methods. How do these approaches differ in terms of data collection and policy evaluation, and what are the advantages of each? Implement both on-policy and off-policy Monte Carlo methods in Rust and compare their performance.