Chapter 6

Temporal-Difference Learning

"Temporal-Difference learning stands at the heart of reinforcement learning, blending the elegance of theory with the power of practical implementation." — Richard Sutton

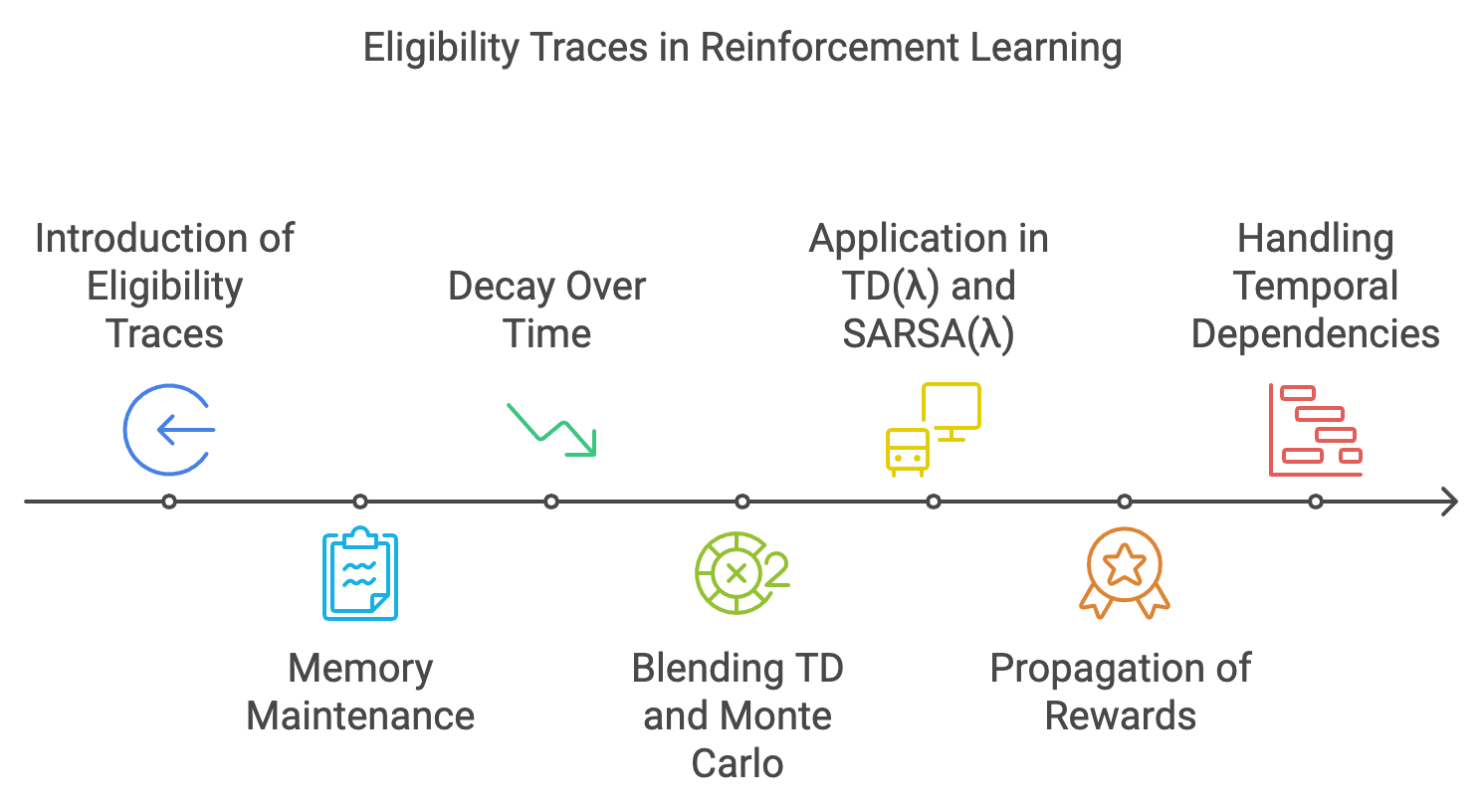

Chapter 6 of RLVR provides an in-depth exploration of Temporal-Difference (TD) learning, a crucial methodology in reinforcement learning that combines the strengths of both Monte Carlo methods and dynamic programming. This chapter begins with an introduction to the fundamentals of TD learning, explaining how it enables value updates after each step of an episode, rather than waiting for its conclusion. Readers will gain a solid understanding of key concepts such as bootstrapping, TD error, and the significance of real-time updates in achieving computational efficiency. The chapter then delves into SARSA, an on-policy TD control method, illustrating how it updates the policy based on actual actions taken and explores the balance between exploration and exploitation. Practical Rust implementations help solidify understanding by guiding readers through building SARSA for various tasks. The chapter also covers Q-Learning, a powerful off-policy TD method that updates the value function based on the optimal action, offering flexibility in learning the optimal policy while following a different behavior policy. This section provides hands-on exercises in Rust, emphasizing the differences between on-policy and off-policy learning. Next, the chapter introduces n-Step TD methods, which extend TD(0) by considering multiple steps before making an update, offering a spectrum of algorithms that bridge the gap between TD and Monte Carlo methods. The final section discusses eligibility traces and TD(λ), a generalization of TD methods that uses eligibility traces to combine short-term and long-term returns, offering a flexible approach to credit assignment in RL. Through this comprehensive chapter, readers will gain both theoretical insights and practical experience in implementing, experimenting with, and optimizing TD learning algorithms using Rust.

6.1. Introduction to Temporal-Difference (TD) Learning

Temporal-Difference (TD) learning methods are a cornerstone of modern reinforcement learning, tracing their origins to the foundational principles of dynamic programming and Monte Carlo methods. These two paradigms shaped early approaches to sequential decision-making, but their limitations spurred the development of more flexible and efficient learning algorithms.

Dynamic programming, pioneered by Richard Bellman in the 1950s, introduced the Bellman equation as a framework for solving sequential decision problems. The Bellman equation provided a way to decompose complex problems into smaller, manageable subproblems, laying the groundwork for algorithms such as policy iteration and value iteration. These methods relied on the principle of bootstrapping—updating value estimates based on the values of successor states. However, dynamic programming techniques required a complete model of the environment’s dynamics, including transition probabilities and rewards. Additionally, their computational cost made them impractical for large or high-dimensional state spaces.

Monte Carlo methods emerged as an alternative in the 1970s, offering a model-free approach to learning value functions by sampling returns from complete episodes. Unlike dynamic programming, Monte Carlo methods did not require explicit knowledge of the environment, making them more versatile. However, their reliance on full episodes for updates introduced delays and inefficiencies, particularly in environments with long episodes or continuous tasks.

Figure 1: Key milestone and evolution of RL methods.

In the late 20th century, researchers sought to combine the strengths of dynamic programming’s bootstrapping and Monte Carlo’s model-free learning. This effort culminated in Richard Sutton’s seminal work in 1988, where he introduced the concept of Temporal-Difference (TD) learning in his paper Learning to Predict by the Methods of Temporal Differences. TD learning proposed a novel framework that leveraged bootstrapping to update value estimates incrementally after each step, rather than waiting for the end of an episode.

The key innovation of TD learning was its ability to update value functions using temporal differences—the discrepancy between successive value estimates. This incremental approach allowed TD methods to operate in real-time, adapting quickly to changing environments and enabling learning in continuous or ongoing tasks. By combining the advantages of Monte Carlo’s sample-based learning and dynamic programming’s bootstrapping, TD learning provided a versatile and efficient method for reinforcement learning.

The introduction of TD learning revolutionized reinforcement learning and paved the way for subsequent algorithmic advancements. Key developments include:

TD(λ): Extending TD learning with eligibility traces, TD(λ) generalized the algorithm to incorporate returns over multiple steps, creating a continuum between TD(0) (single-step updates) and Monte Carlo methods (full-episode updates).

Q-Learning: An off-policy TD control algorithm introduced by Chris Watkins in 1989, Q-Learning built on TD principles to learn optimal policies while allowing exploratory behavior.

Actor-Critic Methods: Combining TD learning with policy-based approaches, Actor-Critic methods leveraged TD updates to guide policy improvements, enabling efficient learning in complex environments.

TD methods became the foundation for deep reinforcement learning advancements in the 2010s, where they were integrated with neural networks to tackle high-dimensional and complex tasks. For example, Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) use TD principles to update action-value functions while leveraging deep learning for function approximation.

Figure 2: The evolution of TD learning with three major milestones.

At its core, Temporal-Difference learning is characterized by its incremental updates and reliance on bootstrapping. Unlike Monte Carlo methods, which estimate returns based on complete episodes, TD learning updates value functions using:

$$ V(s) \leftarrow V(s) + \alpha [r + \gamma V(s') - V(s)], \text{or} $$

$$V(s) \leftarrow V(s) + \alpha \delta.$$

where $V(s)$ is the value of the current state, $r$ is the immediate reward, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $V(s')$ is the value of the next state, $\alpha$ is the learning rate, and $\delta=r + \gamma V(s') - V(s)$ is TD error. This formulation enables agents to update their estimates after each transition, adapting to new information in real-time.

The flexibility and efficiency of TD learning have made it an enduring and fundamental method in reinforcement learning. Its adaptability to dynamic and stochastic environments, combined with its compatibility with both tabular and function approximation methods, ensures its continued relevance in advancing the field.

The core idea behind TD learning is the TD error, which represents the difference between the expected value of a state and the observed reward-plus-discounted-value of the next state. The TD error serves as the driving force for learning, guiding updates to the value function. Mathematically, the TD error is expressed as:

$$\delta_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma V(S_{t+1}) - V(S_t),$$

where:

$\delta_t$ is the TD error at time $t$,

$R_{t+1}$ is the reward observed after transitioning to the next state $S_{t+1}$,

$V(S_t)$ and $V(S_{t+1})$ are the value estimates of the current and next states,

$\gamma$ is the discount factor, determining the importance of future rewards.

By incrementally updating the value function $V(S_t)$ using the TD error, TD learning achieves faster convergence compared to Monte Carlo methods while maintaining the flexibility of a model-free approach.

Temporal-Difference (TD) learning can be likened to how an investor updates their understanding of a stock’s value throughout the day. Instead of waiting for the end-of-day report to make adjustments, the investor reacts to real-time price fluctuations, incorporating new information step by step. This dynamic approach allows for quicker adaptation to market changes, mirroring how TD learning updates value estimates incrementally during an episode rather than waiting for its conclusion.

The defining feature of Temporal-Difference (TD) learning is bootstrapping, a process where value updates rely on current estimates of future values rather than waiting for full returns. This mechanism allows TD learning to balance computational efficiency with real-time adaptability. Bootstrapping distinguishes TD learning from two other foundational paradigms: Monte Carlo methods and dynamic programming.

Monte Carlo methods compute the value of a state or action based on the average returns observed over entire episodes. While this approach provides unbiased estimates, it requires waiting until the episode concludes before making updates. This delay makes Monte Carlo methods less efficient in environments with long or continuous episodes, where immediate updates are desirable. Dynamic programming, on the other hand, relies on a complete model of the environment's dynamics, including transition probabilities and reward functions. By systematically solving the Bellman equation, dynamic programming provides optimal solutions but requires full knowledge of the environment, limiting its applicability in scenarios where the model is unknown or too complex to compute.

TD learning bridges these two approaches by enabling incremental updates based solely on observed transitions and the agent’s current estimates. It is model-free, requiring no prior knowledge of the environment, and supports real-time learning, making it a versatile and practical method for reinforcement learning.

One of the primary advantages of TD learning is its ability to perform real-time updates, which enables agents to adapt during ongoing interactions with the environment. This characteristic is particularly valuable in several scenarios. First, for tasks with long or continuous episodes, waiting until the end of the episode to update values, as in Monte Carlo methods, would significantly delay learning. Second, in dynamic environments where conditions can change rapidly, real-time updates allow the agent to respond immediately, ensuring its value estimates remain relevant. Lastly, when data is sparse or costly to obtain, TD learning’s incremental updates make the most of every observed transition, maximizing learning efficiency.

Consider, for example, a robotic navigation task. TD learning enables the robot to adjust its path based on immediate feedback, such as avoiding obstacles or finding a shortcut, without needing to complete its journey before learning. This incremental approach not only improves efficiency but also ensures adaptability in real-world environments that are often unpredictable and dynamic.

The principles of TD learning have broad implications for reinforcement learning. By updating values step-by-step, TD learning minimizes delays and reduces computational overhead, making it highly efficient. Additionally, it scales well to large or infinite state spaces when combined with function approximation techniques, enabling its application to complex problems. Furthermore, TD methods are highly versatile, suitable for both episodic tasks with clear endpoints and continuous tasks that require ongoing adaptation. These characteristics make TD learning indispensable for a wide range of applications, including games, robotics, finance, and healthcare.

By combining the strengths of Monte Carlo methods and dynamic programming while overcoming their limitations, TD learning has become a cornerstone of reinforcement learning. Its ability to update estimates in real time using bootstrapping and TD errors allows agents to learn efficiently and effectively, even in complex and dynamic environments.

TD(0) is the simplest form of TD learning, where updates to the value function are based solely on the immediate transition between states. The update rule for TD(0) is:

$$ V(S_t) \leftarrow V(S_t) + \alpha \delta_t, $$

where:

$\alpha$ is the learning rate, controlling the magnitude of updates,

$\delta_t$ is the TD error, as defined earlier.

The learning rate $\alpha$ determines how quickly the agent adapts to new information, while the discount factor $\gamma$ balances the emphasis between immediate and future rewards. A higher $\gamma$ places more weight on future rewards, while a lower $\gamma$ prioritizes immediate outcomes.

Temporal Difference (TD) learning is a foundational reinforcement learning (RL) approach that combines the strengths of Monte Carlo (MC) methods and Dynamic Programming (DP). Unlike MC, which relies on complete episodes to update value functions, TD updates estimates incrementally after each step, allowing it to learn directly from incomplete episodes. The provided code implements TD(0), the simplest form of TD learning, to estimate the value function for a grid-world environment. TD(0) uses bootstrapping, where updates are based on the current reward and the value of the next state, enabling faster and more efficient learning in environments with stochastic or dynamic transitions.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// Apply TD(0) to estimate the value function

fn td_zero(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = rng.gen_range(0..4); // Random action selection

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let current_value = *value_function.get(&state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_value = *value_function.get(&next_state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Compute TD error and update value function

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_value - current_value;

value_function

.entry(state)

.and_modify(|v| *v += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

value_function

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let value_function = td_zero(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma);

println!("Estimated Value Function: {:?}", value_function);

}

The td_zero function iteratively updates the value function for each state in the grid-world environment. For a fixed number of episodes, the agent starts at the initial state and takes random actions to explore the environment. Each action results in a transition to a new state, with a reward of $-1$ for non-goal states and $0$ for the goal state. The value function for the current state is updated based on the TD error, which is the difference between the observed reward plus the discounted value of the next state and the current estimate. This error is scaled by the learning rate ($\alpha$) to adjust the value incrementally. By iteratively applying this process, the value function converges to an estimate that reflects the expected cumulative reward for each state, enabling the agent to evaluate states effectively without requiring complete episodes.

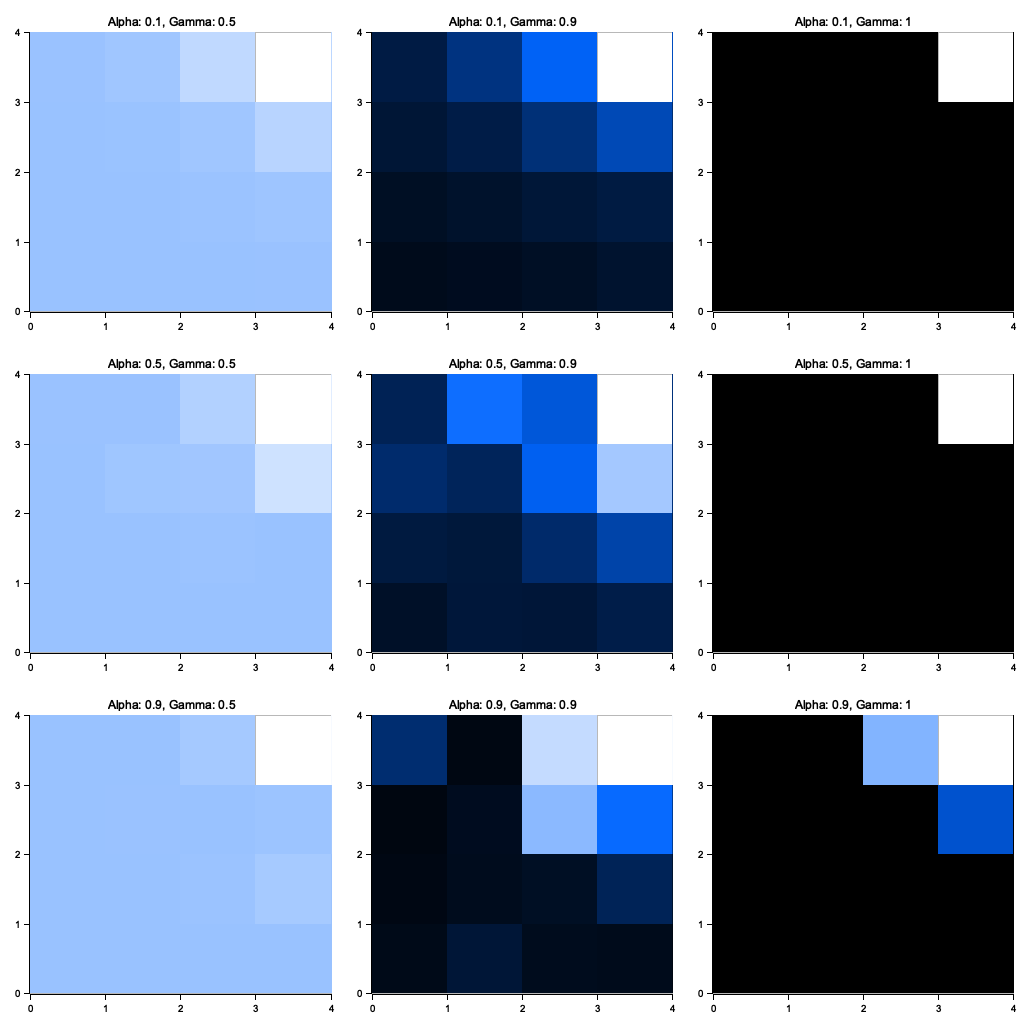

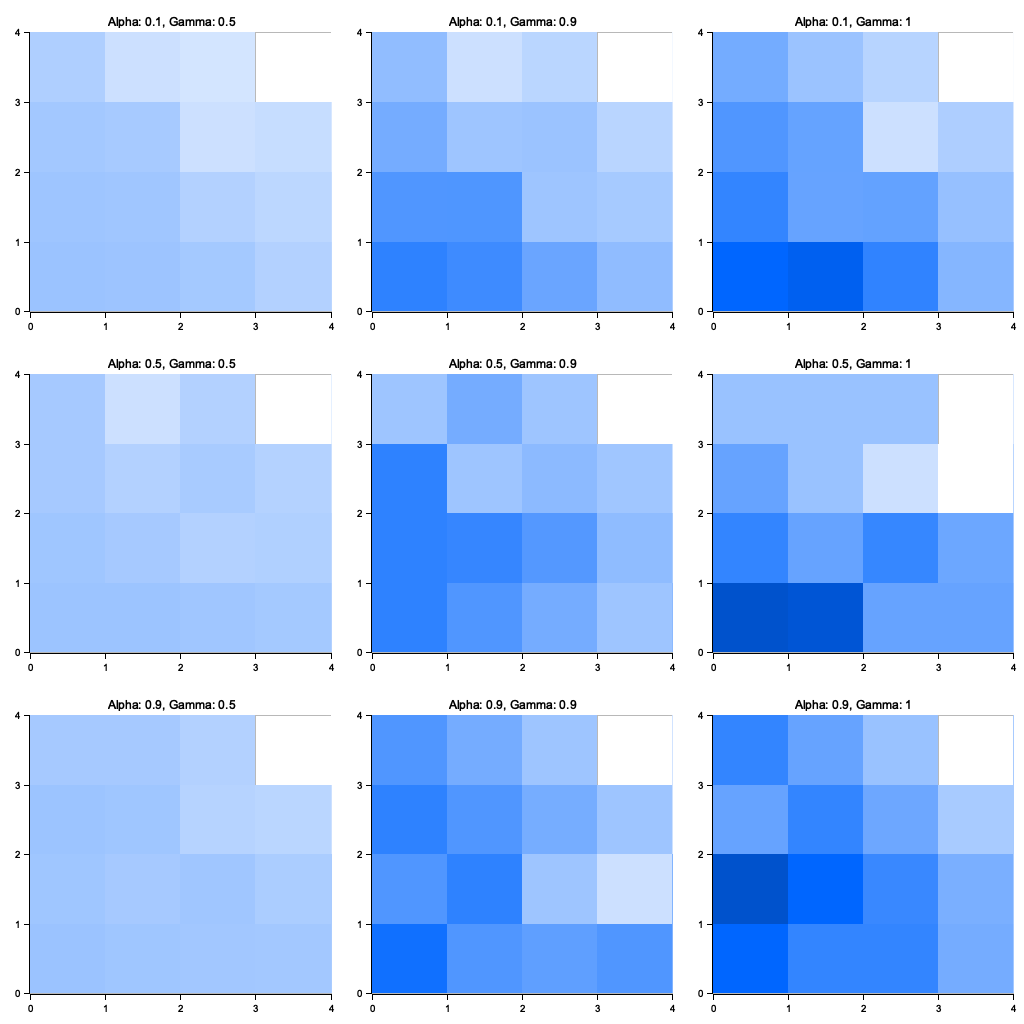

The revised Rust code below builds upon the initial version by incorporating dynamic visualizations of how varying learning rates ($\alpha$) and discount factors ($\gamma$) influence the temporal difference (TD(0)) learning process. Unlike the initial version, which merely printed the resulting value function for different parameters, this version utilizes the plotters crate to generate a consolidated visualization. These visualizations provide an intuitive representation of the value function's convergence across different parameter settings, making it easier to analyze the effects of $\alpha$ and $\gamma$ on learning.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 };

(next_state, reward)

}

}

fn td_zero(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = rng.gen_range(0..4);

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let current_value = *value_function.get(&state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_value = *value_function.get(&next_state).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_value - current_value;

value_function

.entry(state)

.and_modify(|v| *v += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

value_function

}

fn visualize_results(

results: &Vec<(f64, f64, HashMap<(usize, usize), f64>)>,

grid_size: usize,

output_path: &str,

) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(output_path, (1024, 1024)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let areas = root.split_evenly((3, 3)); // Assuming 3x3 grid for alpha and gamma combinations

for (idx, ((alpha, gamma, value_function), area)) in results.iter().zip(areas.iter()).enumerate()

{

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(area)

.caption(format!("Alpha: {}, Gamma: {}", alpha, gamma), ("sans-serif", 15))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(20)

.y_label_area_size(20)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..grid_size as i32, 0..grid_size as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

for ((x, y), value) in value_function {

let intensity = (*value).max(-10.0).min(0.0) / -10.0; // Normalize value for color intensity

chart

.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

[

(x.clone() as i32, y.clone() as i32),

((x + 1).try_into().unwrap(), (y + 1).try_into().unwrap())

],

ShapeStyle::from(&HSLColor(0.6, 1.0, 1.0 - intensity)).filled(),

)))

.unwrap();

}

}

root.present().unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let learning_rates = vec![0.1, 0.5, 0.9];

let discount_factors = vec![0.5, 0.9, 1.0];

let mut results = Vec::new();

for &alpha in &learning_rates {

for &gamma in &discount_factors {

let value_function = td_zero(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma);

results.push((alpha, gamma, value_function));

}

}

visualize_results(&results, grid_world.size, "output.png");

}

The program simulates a 4x4 GridWorld environment where an agent learns the value of states using the TD(0) algorithm. The learning process involves iteratively updating the value function for each state based on the temporal difference error calculated during episodes. The code systematically varies $\alpha$ (learning rate) and $\gamma$ (discount factor), generating value functions for all combinations of these parameters. It then visualizes the results using the plotters crate, where each grid cell’s color intensity represents the learned value of that state. These visualizations are arranged into a single 3x3 image, with captions identifying the corresponding parameter values.

Figure 3: Plotters visualization of the experiment.

The combined visualization illustrates the interplay between $\alpha$ and $\gamma$ in the TD(0) learning process. Higher $\alpha$ values generally lead to faster convergence but may introduce instability, resulting in noisier value functions. Conversely, lower $\alpha$ values yield slower yet smoother convergence. Similarly, higher $\gamma$ values prioritize long-term rewards, often producing more pronounced value gradients, whereas lower $\gamma$ values focus on immediate rewards, leading to less distinct value differentiation. The visualizations highlight these trade-offs, allowing users to select parameter combinations that balance convergence speed and stability for their specific use case.

By integrating theoretical concepts with practical Rust implementations, this section provides a comprehensive introduction to Temporal-Difference learning. The examples illustrate the versatility and efficiency of TD methods, offering readers valuable insights into real-time value updates in reinforcement learning tasks.

6.2. SARSA: On-Policy TD Control

SARSA (State-Action-Reward-State-Action) emerged as a refinement in the reinforcement learning paradigm, specifically addressing the need for on-policy methods that integrate exploration strategies effectively. While its foundational principles align with Temporal-Difference (TD) learning, SARSA’s origins are distinct in its focus on learning policies that are consistent with the agent’s actual behavior.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, research in reinforcement learning was dominated by efforts to develop model-free algorithms that could balance learning efficiency and adaptability. While off-policy methods like Q-learning, introduced by Chris Watkins in 1989, demonstrated the potential for learning optimal policies by decoupling the learning and behavior policies, they also highlighted challenges in scenarios where exploration was crucial. Off-policy approaches often prioritized exploitation, making it difficult to integrate strategies like epsilon-greedy exploration without destabilizing the learning process.

Figure 4: How SARSA algorithm works.

SARSA was introduced in the mid-1990s as an on-policy alternative that retained the agent's behavior policy as the basis for learning. This approach ensured that the updates to the action-value function $Q(s, a)$ were directly tied to the actions actually taken by the agent, rather than hypothetical optimal actions. By doing so, SARSA provided a natural way to incorporate exploration strategies into the learning process, offering a more stable framework for policy improvement in uncertain environments.

The name SARSA reflects the sequence of elements—state, action, reward, next state, and next action—used in its update rule, emphasizing the continuity between the agent’s actions and its learning process. This method became particularly appealing for scenarios requiring safe or controlled exploration, such as navigation tasks, where the agent's behavior policy must align closely with its learned policy.

SARSA's introduction expanded the reinforcement learning toolkit, providing a method that complemented existing algorithms by focusing on the interplay between exploration and policy consistency. It remains a widely studied and applied algorithm, valued for its simplicity and effectiveness in tasks where alignment between learning and behavior is essential.

SARSA is a fundamental on-policy Temporal-Difference (TD) control algorithm in reinforcement learning. Unlike off-policy methods such as Q-learning, SARSA learns the action-value function $Q(s, a)$ based on the actions that the current policy actually takes, rather than the optimal actions. This approach ensures that SARSA remains consistent with the policy being followed, allowing for natural integration of exploration strategies such as epsilon-greedy.

The SARSA update rule is mathematically expressed as:

$$ Q(s_t, a_t) \leftarrow Q(s_t, a_t) + \alpha \left[ R_{t+1} + \gamma Q(s_{t+1}, a_{t+1}) - Q(s_t, a_t) \right], $$

where:

$\alpha$ is the learning rate,

$\gamma$ is the discount factor,

$Q(s_t, a_t)$ is the estimated value of taking action $a_t$ in state $s_t$,

$R_{t+1}$ is the reward for transitioning to the next state $s_{t+1}$,

$Q(s_{t+1}, a_{t+1})$ is the value of the next state-action pair under the current policy.

An intuitive analogy for SARSA is navigating through a maze. Imagine you’re trying to find the exit, but you can only update your strategy based on the paths you actually take (even if they are suboptimal), rather than assuming you always make the best move.

SARSA’s update rule captures the essence of on-policy learning. The TD error in SARSA depends on the next action $a_{t+1}$ selected by the policy. This dependence ensures that SARSA takes into account the exploration strategy defined by the policy, such as epsilon-greedy. This makes SARSA particularly suitable for real-world scenarios where agents must balance exploration (trying out new actions) and exploitation (optimizing for rewards).

The exploration-exploitation trade-off is built into SARSA because the agent updates its action-value estimates based on actual, potentially exploratory actions. This ensures that even suboptimal actions contribute to learning, providing a comprehensive understanding of the environment.

SARSA converges to the optimal policy under specific conditions:

Exploration: The policy must explore all state-action pairs infinitely often. This can be achieved using an epsilon-greedy policy, where $\epsilon$-randomness ensures exploration.

Learning Rate: The learning rate $\alpha$ must satisfy the conditions $\sum_{t=1}^\infty \alpha_t = \infty$ and $\sum_{t=1}^\infty \alpha_t^2 < \infty$ to guarantee convergence.

Stationary Environment: The environment must not change during the learning process.

These conditions ensure that SARSA iteratively improves the policy while avoiding premature convergence or oscillations.

The following implementation demonstrates SARSA applied to a simple grid world environment. The agent learns to navigate the grid using an epsilon-greedy policy, balancing exploration and exploitation. The implementation explores how varying epsilon values affect the learning process. SARSA is an on-policy reinforcement learning algorithm used to estimate the optimal action-value function for a given environment. Unlike off-policy methods like Q-learning, SARSA follows the agent's current policy, updating Q-values based on the action it actually takes. This approach incorporates the interaction between the agent's exploration and exploitation strategies, making SARSA particularly well-suited for environments where the exploration behavior is critical to learning.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// SARSA algorithm

fn sarsa(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

let mut action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let next_action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(next_state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(next_state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_q = *q_values.get(&(next_state, next_action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update Q-value using SARSA update rule

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

action = next_action;

}

}

q_values

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let q_values = sarsa(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Learned Q-Values: {:?}", q_values);

}

SARSA operates by iteratively updating Q-values using the tuple $(s, a, r, s', a')$, which represents the current state $s$, chosen action aaa, received reward $r$, next state $s'$, and the next action $a'$. The algorithm begins in an initial state, selects an action using an $\epsilon$-greedy policy, and observes the subsequent state and reward. The Q-value is then updated using the temporal difference (TD) error, calculated as the difference between the current Q-value and the reward plus the discounted Q-value of the next state-action pair. By repeating this process over multiple episodes, SARSA learns a policy that balances exploration (via random actions) and exploitation (via the greedy policy), gradually converging to the optimal Q-values.

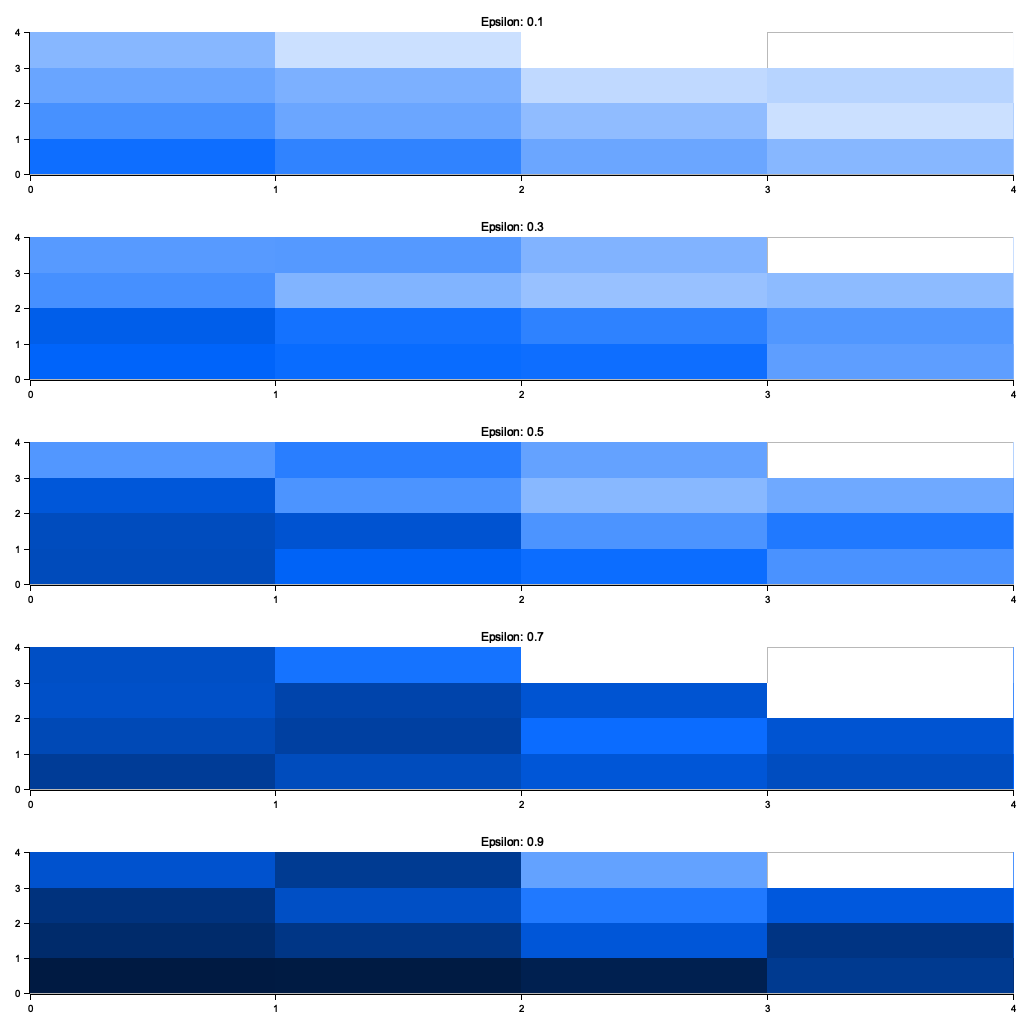

The modified code extends the initial SARSA implementation by introducing an experiment to analyze the impact of varying $\epsilon$ values on the learning process. While the original code used a fixed $\epsilon$ value, this version systematically evaluates multiple values ranging from 0.1 to 0.9, representing different balances between exploration and exploitation. The results are visualized using heatmaps for each $\epsilon$, allowing a comparative analysis of the learned Q-values across the grid world for varying exploration strategies.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// SARSA algorithm

fn sarsa(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

let mut action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let next_action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(next_state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(next_state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_q = *q_values.get(&(next_state, next_action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update Q-value using SARSA update rule

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

action = next_action;

}

}

q_values

}

// Visualize the impact of varying epsilon

fn visualize_epsilon_impact(

epsilons: Vec<f64>,

grid_size: usize,

output_path: &str,

results: Vec<(f64, HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>)>,

) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(output_path, (1024, 1024)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let areas = root.split_evenly((epsilons.len(), 1)); // One row for each epsilon value

for (area, (epsilon, q_values)) in areas.iter().zip(results.iter()) {

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(area)

.caption(format!("Epsilon: {}", epsilon), ("sans-serif", 15))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(20)

.y_label_area_size(20)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..grid_size as i32, 0..grid_size as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

for (((x, y), _), value) in q_values.iter() {

let intensity = (*value).max(-10.0).min(0.0) / -10.0; // Normalize value for color intensity

chart

.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

// Convert usize to i32 using try_into().unwrap() to handle potential conversion

[(*x as i32, *y as i32), ((*x + 1).try_into().unwrap(), (*y + 1).try_into().unwrap())],

ShapeStyle::from(&HSLColor(0.6, 1.0, 1.0 - intensity)).filled(),

)))

.unwrap();

}

}

root.present().unwrap();

println!("Visualization completed. Saved to {}", output_path);

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilons = vec![0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9];

let mut results = Vec::new();

for &epsilon in &epsilons {

println!("Running SARSA for Epsilon: {}", epsilon);

let q_values = sarsa(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

results.push((epsilon, q_values));

}

visualize_epsilon_impact(epsilons, grid_world.size, "epsilon_impact.png", results);

}

The visualization highlights the trade-off between exploration and exploitation driven by $\epsilon$. At low $\epsilon$ values (e.g., 0.1), the agent primarily exploits its current knowledge, leading to quicker convergence but potentially suboptimal Q-values due to limited exploration. In contrast, higher $\epsilon$ values (e.g., 0.7 or 0.9) promote extensive exploration, enabling the agent to discover more states and actions, resulting in more robust Q-values but at the cost of slower convergence. These findings underscore the importance of choosing an appropriate $\epsilon$ value to balance learning efficiency and state-action coverage in reinforcement learning.

Figure 5: Plotters visualization of varying the value of $\epsilon$.

The next experiment compares the SARSA and Q-learning algorithms, focusing on their convergence speed and stability in a 4x4 grid world environment. Both algorithms are tasked with learning the Q-values for state-action pairs over 1,000 episodes, using identical learning rate ($\alpha = 0.1$), discount factor ($\gamma = 0.9$), and exploration probability ($\epsilon = 0.1$). The key goal is to highlight the differences between SARSA's on-policy updates, which depend on the agent's actual behavior, and Q-learning's off-policy updates, which rely on optimal action assumptions for the next state.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// SARSA algorithm

fn sarsa(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

let mut action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let next_action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(next_state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(next_state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_q = *q_values.get(&(next_state, next_action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update Q-value using SARSA update rule

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

action = next_action;

}

}

q_values

}

// Q-learning algorithm

fn q_learning(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let next_max_q = (0..4)

.map(|a| *q_values.get(&(next_state, a)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.fold(f64::MIN, f64::max); // Max Q-value for the next state

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update Q-value using Q-learning update rule

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_max_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

q_values

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilon = 0.1;

println!("Running SARSA...");

let sarsa_q_values = sarsa(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("SARSA Q-Values: {:?}", sarsa_q_values);

println!("Running Q-Learning...");

let q_learning_q_values = q_learning(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Q-Learning Q-Values: {:?}", q_learning_q_values);

println!("Comparison completed.");

}

The code implements both SARSA and Q-learning as separate functions, each updating Q-values based on their respective update rules. SARSA computes updates using the reward and the Q-value of the next state-action pair ($(s', a')$) based on the agent's chosen policy, promoting stability by aligning updates with the agent's exploration strategy. In contrast, Q-learning updates Q-values using the maximum action-value for the next state ($(s', \max_a Q(s', a))$), emphasizing optimality and potentially faster convergence. Both algorithms interact with a shared grid world environment, taking random or greedy actions based on an $\epsilon$-greedy policy.

The results demonstrate notable differences between the algorithms. SARSA tends to converge more steadily as its updates align with the agent's actual policy, making it robust in environments with significant exploration. However, it may take longer to converge fully to the optimal Q-values. On the other hand, Q-learning often converges faster by directly targeting optimal action-values, but this can lead to instability, especially if the exploration probability ($\epsilon$) is high, as it might overestimate action values. These differences emphasize the trade-off between stability and convergence speed when selecting between on-policy and off-policy methods.

By combining theoretical insights with practical Rust implementations, this section provides readers with a comprehensive understanding of SARSA, its applications, and its strengths as an on-policy TD control method. The examples and experiments offer hands-on experience with one of the most widely used algorithms in reinforcement learning.

6.3. Q-Learning: Off-Policy TD Control

Q-Learning, introduced by Chris Watkins in 1989, marked a significant milestone in the evolution of reinforcement learning algorithms. Its development was driven by the need for methods that could learn optimal policies in environments where explicit models were unavailable or computationally infeasible to use. At the time, most reinforcement learning methods were either model-based, relying on dynamic programming techniques, or on-policy, requiring the agent's learned policy to align with its behavior policy.

Watkins's key insight was to decouple the learning process from the agent’s behavior policy, giving rise to the concept of off-policy learning. This innovation addressed a critical limitation of on-policy methods like SARSA, which updated value functions based only on the actions taken by the current policy. By allowing the action-value function $Q(s, a)$ to be updated based on the optimal action, regardless of the agent’s exploratory behavior, Q-Learning enabled agents to explore their environment freely while still learning toward the optimal policy.

Figure 6: The evolution and impact of Q-learning method.

The algorithm’s foundation lies in the Bellman equation, which provides a recursive relationship for computing value functions. Watkins extended this idea by introducing the Q-function, representing the expected utility of taking an action $a$ in a state $s$ and following the optimal policy thereafter. The Q-Learning update rule incrementally refines the Q-function using a Temporal-Difference (TD) approach, making it both computationally efficient and robust to stochastic environments.

Q-Learning’s off-policy nature became a pivotal feature, allowing agents to explore using strategies like epsilon-greedy or Boltzmann exploration while still converging to the optimal policy. This flexibility made Q-Learning a versatile and powerful algorithm, particularly well-suited for complex, dynamic environments where exploration is critical.

Since its introduction, Q-Learning has influenced a wide range of applications and advancements in reinforcement learning, from robotics to game playing. It served as a foundational building block for more advanced algorithms, such as Deep Q-Networks (DQNs), which combine Q-Learning with deep learning to handle high-dimensional state spaces. Today, Q-Learning remains a cornerstone of reinforcement learning, celebrated for its simplicity, robustness, and enduring impact on the field.

Till now, Q-Learning is one of the most influential algorithms in reinforcement learning, known for its ability to learn the optimal policy while following any behavior policy. Unlike on-policy methods such as SARSA, Q-Learning is an off-policy Temporal-Difference (TD) control algorithm. This means it updates its action-value function $Q(s, a)$ based on the optimal action for the next state, rather than the action actually taken by the agent. This property allows Q-Learning to converge to the optimal policy, even when the agent explores the environment using a suboptimal or exploratory behavior policy.

The update rule for Q-Learning is defined as:

$$ Q(s_t, a_t) \leftarrow Q(s_t, a_t) + \alpha \left[ R_{t+1} + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s_{t+1}, a') - Q(s_t, a_t) \right], $$

where:

$\alpha$ is the learning rate, controlling the step size of updates,

$\gamma$ is the discount factor, balancing the importance of immediate versus future rewards,

$R_{t+1}$ is the reward obtained for transitioning to state $s_{t+1}$,

$\max_{a'} Q(s_{t+1}, a')$ represents the value of the optimal action in the next state.

An intuitive analogy for Q-Learning is optimizing a travel route by always considering the shortest possible path from your current location to the destination, even if your current path involves detours for exploration.

On-Policy vs. Off-Policy Learning: In on-policy methods like SARSA, the action-value function is updated based on the action actually taken, making the updates consistent with the policy being followed. In contrast, Q-Learning separates the behavior policy (used for exploration) from the target policy (used for learning). The target policy is implicitly defined as the greedy policy that always selects the action with the highest Q-value.

Role of the Max Operator: The max operator in Q-Learning ensures that the agent always considers the best possible future reward when updating its Q-values. This allows the algorithm to converge to the optimal policy by prioritizing the most rewarding actions in the long run.

Impact of Learning Rate and Discount Factor: The learning rate α\\alphaα determines how much the agent updates its Q-values based on new information, while the discount factor $\gamma$ controls the agent’s emphasis on future rewards. High $\alpha$ values can lead to rapid but unstable learning, while low $\alpha$ values may result in slow convergence. Similarly, a high $\gamma$ encourages long-term planning, while a low $\gamma$ prioritizes immediate rewards.

This code implements a Q-learning algorithm to solve a 4x4 grid world environment, where the objective is to find an optimal policy for reaching a goal state at the bottom-right corner from the top-left corner. The algorithm employs a reinforcement learning approach to iteratively update action-value (Q) estimates for each state-action pair, allowing the agent to balance exploration and exploitation through an $\epsilon$-greedy policy. The grid world rewards the agent with -1 for every step until it reaches the goal, incentivizing shorter paths.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// Q-Learning algorithm

fn q_learning(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let max_next_q = (0..4)

.map(|a| *q_values.get(&(next_state, a)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

// Update Q-value using Q-Learning update rule

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let td_error = reward + gamma * max_next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

q_values

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let q_values = q_learning(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Learned Q-Values: {:?}", q_values);

}

The q_learning function initializes a Q-table as a hash map and simulates the agent’s interaction with the grid world over multiple episodes. For each episode, the agent begins at the top-left corner and selects actions using an $\epsilon$-greedy policy—random actions with probability $\epsilon$ (exploration) or the action with the highest Q-value for the current state (exploitation). The agent receives a reward and transitions to the next state, where the maximum Q-value of the next state $\max_a Q(s', a)$ is used to calculate the temporal difference (TD) error. The Q-value for the current state-action pair is updated using this error and a learning rate ($\alpha$). This process repeats until the agent reaches the goal state, and the algorithm iteratively improves the policy as it learns the optimal path to the goal.

Compared to the initial version, the code below introduces an experiment to analyze how varying the learning rate ($\alpha$) and discount factor ($\gamma$) affects the Q-learning process in a 4x4 grid world. By iterating over multiple combinations of $\alpha$ and $\gamma$, the code evaluates their impact on the convergence of Q-values. The results are visualized using heatmaps, where each cell represents the Q-values learned for a specific $\alpha, \gamma$ combination, providing an intuitive way to understand their influence on the learning dynamics.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// Q-Learning algorithm

fn q_learning(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0); // Start at the top-left corner

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let max_next_q = (0..4)

.map(|a| *q_values.get(&(next_state, a)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

// Update Q-value using Q-Learning update rule

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let td_error = reward + gamma * max_next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

q_values

}

// Visualize the results for varying alpha and gamma

fn visualize_alpha_gamma_impact(

alphas: Vec<f64>,

gammas: Vec<f64>,

grid_size: usize,

output_path: &str,

results: Vec<(f64, f64, HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64>)>,

) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(output_path, (1024, 1024)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let areas = root.split_evenly((alphas.len(), gammas.len())); // Each cell corresponds to an alpha-gamma combination

for (area, (alpha, gamma, q_values)) in areas.iter().zip(results.iter()) {

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(area)

.caption(format!("Alpha: {}, Gamma: {}", alpha, gamma), ("sans-serif", 15))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(20)

.y_label_area_size(20)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..grid_size as i32, 0..grid_size as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

for (((x, y), _), value) in q_values.iter() {

let intensity = (*value).max(-10.0).min(0.0) / -10.0; // Normalize value for color intensity

chart

.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

[(*x as i32, *y as i32), ((*x + 1) as i32, (*y + 1) as i32)],

ShapeStyle::from(&HSLColor(0.6, 1.0, 1.0 - intensity)).filled(),

)))

.unwrap();

}

}

root.present().unwrap();

println!("Visualization completed. Saved to {}", output_path);

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let epsilon = 0.1;

let alphas = vec![0.1, 0.5, 0.9];

let gammas = vec![0.5, 0.9, 1.0];

let mut results = Vec::new();

for &alpha in &alphas {

for &gamma in &gammas {

println!("Running Q-Learning for Alpha: {}, Gamma: {}", alpha, gamma);

let q_values = q_learning(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

results.push((alpha, gamma, q_values));

}

}

visualize_alpha_gamma_impact(alphas, gammas, grid_world.size, "alpha_gamma_impact.png", results);

}

The Q-learning function iteratively updates Q-values for state-action pairs based on the temporal difference (TD) error calculated using rewards and the maximum Q-value of the next state. The main experiment varies $\alpha$ and $\gamma$, running the Q-learning algorithm for each combination across 1,000 episodes. The learned Q-values are then stored for visualization. The visualize_alpha_gamma_impact function generates heatmaps for each combination of parameters, where the color intensity represents the normalized Q-values. The heatmaps are arranged in a grid layout, with rows corresponding to different $\alpha$ values and columns to different $\gamma$ values.

Figure 7: Plotters visualization of the experiment.

The visualizations reveal the trade-offs between learning rate and discount factor in the Q-learning process. Higher $\alpha$ values (e.g., 0.9) lead to faster updates and quicker convergence but can introduce instability, as evident from noisier heatmaps. Lower $\alpha$ values (e.g., 0.1) result in smoother Q-value updates but slower learning. Higher $\gamma$ values (e.g., 1.0) emphasize long-term rewards, creating distinct value gradients that prioritize reaching the goal. Lower $\gamma$ values (e.g., 0.5) focus on immediate rewards, leading to less pronounced value differentiation. These findings highlight the importance of tuning $\alpha$ and $\gamma$ for achieving a balance between learning speed, stability, and prioritization of rewards.

Next experiment compares the performance of Q-Learning (off-policy) and SARSA (on-policy) in a shared 4x4 grid world environment. Both algorithms aim to learn optimal policies for reaching a goal state from a starting state by updating Q-values for state-action pairs over 1,000 episodes. While Q-Learning prioritizes selecting actions based on the maximum future reward (off-policy), SARSA updates Q-values based on the actions actually taken (on-policy), offering a more realistic evaluation of the agent’s policy. The experiment highlights differences in their learning dynamics, convergence, and stability.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the grid world environment

struct GridWorld {

size: usize,

goal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: usize) -> ((usize, usize), f64) {

let next_state = match action {

0 => (state.0.saturating_sub(1), state.1), // Up

1 => (state.0 + 1, state.1.min(self.size - 1)), // Down

2 => (state.0, state.1.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

_ => (state.0, state.1 + 1.min(self.size - 1)), // Right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.goal_state { 0.0 } else { -1.0 }; // Goal state has no penalty

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// Q-Learning algorithm

fn q_learning(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0);

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let max_next_q = (0..4)

.map(|a| *q_values.get(&(next_state, a)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

// Update Q-value using Q-Learning update rule

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let td_error = reward + gamma * max_next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

}

}

q_values

}

// SARSA algorithm

fn sarsa(

grid_world: &GridWorld,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

epsilon: f64,

) -> HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> {

let mut q_values: HashMap<((usize, usize), usize), f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = (0, 0);

let mut action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

while state != grid_world.goal_state {

let (next_state, reward) = grid_world.step(state, action);

let next_action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action (exploration)

} else {

(0..4)

.max_by(|&a, &b| {

q_values

.get(&(next_state, a))

.unwrap_or(&0.0)

.partial_cmp(q_values.get(&(next_state, b)).unwrap_or(&0.0))

.unwrap()

})

.unwrap_or(0) // Greedy action (exploitation)

};

let current_q = *q_values.get(&(state, action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let next_q = *q_values.get(&(next_state, next_action)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update Q-value using SARSA update rule

let td_error = reward + gamma * next_q - current_q;

q_values

.entry((state, action))

.and_modify(|q| *q += alpha * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha * td_error);

state = next_state;

action = next_action;

}

}

q_values

}

fn main() {

let grid_world = GridWorld {

size: 4,

goal_state: (3, 3),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

let epsilon = 0.1;

println!("Running Q-Learning...");

let q_values = q_learning(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Q-Learning Q-Values: {:?}", q_values);

println!("Running SARSA...");

let sarsa_q_values = sarsa(&grid_world, episodes, alpha, gamma, epsilon);

println!("SARSA Q-Values: {:?}", sarsa_q_values);

println!("Comparison completed.");

}

The code implements both Q-Learning and SARSA algorithms, using the same grid world and hyperparameters for fair comparison. Q-Learning updates Q-values using the maximum Q-value of the next state ($\max_a Q(s', a)$), focusing on an idealized optimal policy. SARSA, on the other hand, updates Q-values based on the next action chosen by the agent ($Q(s', a')$), reflecting the agent’s actual policy during learning. Both algorithms use an $\epsilon$-greedy policy for action selection, balancing exploration and exploitation. The Q-values learned by each algorithm are printed for comparative analysis.

The results demonstrate the trade-offs between the two approaches. Q-Learning often converges faster due to its focus on optimal actions, but it can exhibit instability in environments with significant exploration. SARSA, being on-policy, provides more stable learning as it updates Q-values based on the agent’s actual actions, aligning updates with the current exploration strategy. However, this can lead to slower convergence compared to Q-Learning. These insights highlight the importance of choosing the appropriate algorithm based on the stability requirements and the exploration-exploitation balance in a given application.

By integrating theoretical concepts with practical Rust implementations, this section offers a comprehensive understanding of Q-Learning, its strengths as an off-policy TD control method, and its applications in reinforcement learning tasks. The experiments provide hands-on insights into the algorithm’s behavior under different conditions, equipping readers with the tools to apply Q-Learning effectively in real-world scenarios.

6.4. n-Step TD Methods

The development of n-step Temporal Difference (TD) methods represents a natural evolution in reinforcement learning, aimed at unifying and generalizing the strengths of existing approaches like TD(0) and Monte Carlo methods. These methods emerged as researchers sought to balance the trade-offs between computational efficiency and the quality of value estimates.

TD(0), introduced in the foundational work on Temporal Difference learning by Richard Sutton in 1988, updates value estimates incrementally using the immediate reward and a bootstrap estimate of the next state’s value. While computationally efficient and suitable for real-time learning, TD(0) relies heavily on short-term transitions, which can sometimes limit its accuracy in estimating long-term returns.

Monte Carlo methods, on the other hand, estimate value functions by averaging returns over complete episodes. While these methods are unbiased and incorporate long-term outcomes, they require waiting until an episode concludes before updating value estimates. This can be computationally expensive and impractical for tasks involving long or continuous episodes.

Figure 8: The evolution of n-step TD methods.

The introduction of n-step TD methods aimed to bridge this divide by incorporating information from multiple steps into the update process. By using an $n$-step return that sums rewards over $n$ transitions and bootstraps the value estimate after $n$ steps, these methods allow for greater flexibility. For small $n$, n-step TD resembles TD(0), emphasizing short-term updates. As $n$ increases, the method approaches Monte Carlo techniques, capturing more of the long-term return.

The flexibility of the n-step framework made it particularly appealing for reinforcement learning practitioners, as it offered a tunable parameter $n$ to balance bias and variance in value estimates. This framework also paved the way for more advanced algorithms like TD(λ), which generalizes n-step TD methods by averaging over all possible step lengths weighted by a decay parameter $\lambda$.

Since their introduction, n-step TD methods have been instrumental in advancing reinforcement learning, particularly in scenarios where episodic learning is impractical or where a balance between short-term and long-term value estimates is critical. Their impact continues to resonate in modern RL algorithms, influencing the development of multi-step methods used in deep reinforcement learning frameworks.

n-Step Temporal Difference (TD) methods extend the classical TD(0) approach by considering the cumulative return over multiple steps before updating the value function. This technique bridges the gap between TD(0), which updates based on immediate transitions, and Monte Carlo methods, which rely on entire episodes. The n-step framework introduces a flexible spectrum of algorithms, allowing reinforcement learning practitioners to balance computational efficiency and learning accuracy.

The essence of n-Step TD lies in the n-step return, a cumulative reward that includes $n$ steps of observed rewards followed by a bootstrapped estimate from the value function. The n-step return for state $s_t$ is defined as:

$$ G_t^{(n)} = R_{t+1} + \gamma R_{t+2} + \cdots + \gamma^{n-1} R_{t+n} + \gamma^n V(S_{t+n}), $$

where:

$R_{t+1}, R_{t+2}, \dots, R_{t+n}$ are rewards for the next $n$ steps,

$\gamma$ is the discount factor,

$V(S_{t+n})$ is the value of the state after $n$ steps.

The value function is updated as:

$$ V(S_t) \leftarrow V(S_t) + \alpha \left( G_t^{(n)} - V(S_t) \right), $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate.

By choosing different values of nnn, this method provides a spectrum of algorithms:

$n = 1$: The method becomes TD(0), relying entirely on immediate transitions.

$n = \infty$: The method approximates Monte Carlo, using complete episodes for updates.

The parameter $n$ is pivotal in determining the trade-off between bias and variance in the learning process:

Smaller values of $n$: Emphasize immediate rewards, resulting in faster updates but potentially introducing bias due to reliance on short-term information.

Larger values of $n$: Incorporate more future rewards, reducing bias but increasing variance due to noise in longer-term returns.

An analogy for $n$ is deciding the granularity of planning a vacation. Using $n = 1$ is like planning just the next activity, ensuring quick decisions but possibly missing long-term opportunities. Using $n = \infty$ is like planning the entire trip, which ensures a well-thought-out journey but requires extensive effort and may involve unforeseen uncertainties.

The n-Step TD methods and eligibility traces are closely related. Eligibility traces generalize the n-step concept by assigning decaying weights to all prior states based on their recency, effectively combining the strengths of various n-step methods into a unified framework. This connection highlights the flexibility of TD methods in addressing diverse reinforcement learning challenges.

The following implementation demonstrates n-Step TD methods applied to a random walk environment. The agent learns to predict the value function for states by updating based on returns calculated over $n$-step transitions. This code implements an $n$-step TD algorithm to solve a random walk problem in a finite environment. The agent starts at the middle of the environment and learns a value function for each state based on episodic interactions, where it moves left or right randomly until reaching one of the terminal states. The algorithm allows experimentation with varying $n$ values, which control how far into the future rewards are considered when updating the value function. The goal is to analyze how different $n$-step updates influence the learning process.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::Rng;

// Define a random walk environment

struct RandomWalk {

size: usize,

terminal_states: (usize, usize),

}

impl RandomWalk {

fn step(&self, state: usize, action: i32) -> (usize, f64) {

let next_state = if action == -1 {

state.saturating_sub(1) // Move left

} else {

(state + 1).min(self.size - 1) // Move right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.terminal_states.0 || next_state == self.terminal_states.1 {

1.0 // Reward at terminal states

} else {

0.0

};

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// n-Step TD algorithm

fn n_step_td(

random_walk: &RandomWalk,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

n: usize,

) -> HashMap<usize, f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<usize, f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = random_walk.size / 2; // Start at the middle state

let mut states = vec![state];

let mut rewards = Vec::new();

while state != random_walk.terminal_states.0 && state != random_walk.terminal_states.1 {

let action = if rng.gen_bool(0.5) { -1 } else { 1 }; // Random action

let (next_state, reward) = random_walk.step(state, action);

states.push(next_state);

rewards.push(reward);

if states.len() > n {

// Calculate G for n steps

let g: f64 = rewards.iter().take(n).enumerate().fold(0.0, |acc, (i, &r)| {

acc + gamma.powi(i as i32) * r

}) + gamma.powi(n as i32)

* *value_function.get(states.get(n).unwrap_or(&state)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

// Update value function

if !states.is_empty() {

let current_value = value_function.entry(states[0]).or_insert(0.0);

*current_value += alpha * (g - *current_value);

}

// Remove processed state and reward

if !states.is_empty() {

states.remove(0);

}

if !rewards.is_empty() {

rewards.remove(0);

}

}

state = next_state;

}

// Final updates for remaining states

while !states.is_empty() && !rewards.is_empty() {

let g: f64 = rewards.iter().enumerate().fold(0.0, |acc, (i, &r)| {

acc + gamma.powi(i as i32) * r

});

let current_value = value_function.entry(states[0]).or_insert(0.0);

*current_value += alpha * (g - *current_value);

states.remove(0);

rewards.remove(0);

}

}

value_function

}

fn main() {

let random_walk = RandomWalk {

size: 5,

terminal_states: (0, 4),

};

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.9;

for n in [1, 3, 5].iter() {

let value_function = n_step_td(&random_walk, episodes, alpha, gamma, *n);

println!("n: {}, Value Function: {:?}", n, value_function);

}

}

The n_step_td function initializes a value function for all states and simulates episodes where the agent starts in the middle state. At each step, the agent selects an action randomly, transitions to a new state, and receives a reward. The rewards and states are stored, and once enough steps ($n$) are collected, the algorithm computes the return $G$ for the current state by summing discounted rewards and the estimated value of the state $n$ steps ahead. The value function is updated incrementally using the TD error, which is the difference between $G$ and the current estimate. At the end of the episode, any remaining states and rewards are processed to finalize the updates. By adjusting $n$, the algorithm can emphasize short-term or long-term rewards, providing insights into the balance between bias and variance in TD learning.

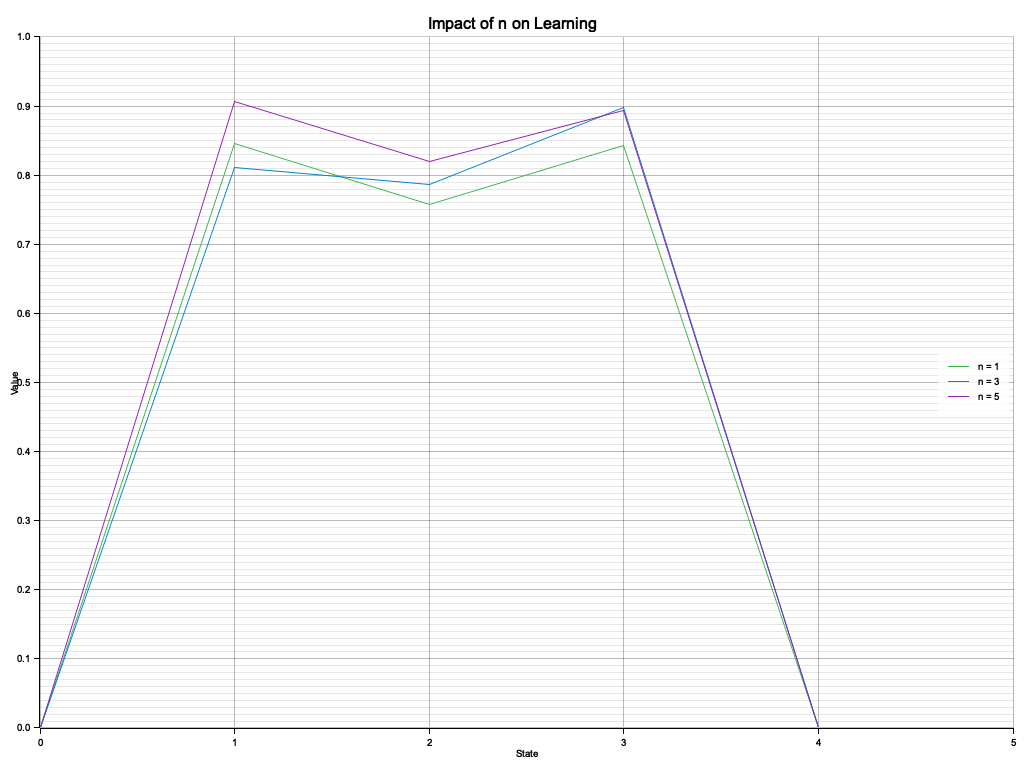

Compared to the previous code, this experiment investigates the impact of varying nnn values in the nnn-step TD algorithm on the learning process in a random walk environment. While the earlier code executed the TD algorithm without a focus on parameter analysis, this version systematically compares $n = 1, 3, 5$ to observe how shorter vs. longer step updates influence learning dynamics. By visualizing the resulting value functions, the experiment highlights the trade-offs between learning speed, stability, and variance introduced by different $n$ values.

use std::collections::HashMap;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

// Define a random walk environment

struct RandomWalk {

size: usize,

terminal_states: (usize, usize),

}

impl RandomWalk {

fn step(&self, state: usize, action: i32) -> (usize, f64) {

let next_state = if action == -1 {

state.saturating_sub(1) // Move left

} else {

(state + 1).min(self.size - 1) // Move right

};

let reward = if next_state == self.terminal_states.0 || next_state == self.terminal_states.1 {

1.0 // Reward at terminal states

} else {

0.0

};

(next_state, reward)

}

}

// n-Step TD algorithm

fn n_step_td(

random_walk: &RandomWalk,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

n: usize,

) -> HashMap<usize, f64> {

let mut value_function: HashMap<usize, f64> = HashMap::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = random_walk.size / 2; // Start at the middle state

let mut states = vec![state];

let mut rewards = Vec::new();

while state != random_walk.terminal_states.0 && state != random_walk.terminal_states.1 {

let action = if rng.gen_bool(0.5) { -1 } else { 1 }; // Random action

let (next_state, reward) = random_walk.step(state, action);

states.push(next_state);

rewards.push(reward);

if states.len() > n {

let g: f64 = rewards.iter().take(n).enumerate().fold(0.0, |acc, (i, &r)| {

acc + gamma.powi(i as i32) * r

}) + gamma.powi(n as i32)

* *value_function.get(states.get(n).unwrap_or(&state)).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let current_value = value_function.entry(states[0]).or_insert(0.0);

*current_value += alpha * (g - *current_value);

states.remove(0);

rewards.remove(0);

}

state = next_state;

}

// Final updates for remaining states

while !states.is_empty() && !rewards.is_empty() {

let g: f64 = rewards.iter().enumerate().fold(0.0, |acc, (i, &r)| {

acc + gamma.powi(i as i32) * r

});

let current_value = value_function.entry(states[0]).or_insert(0.0);

*current_value += alpha * (g - *current_value);

states.remove(0);

rewards.remove(0);

}

}

value_function

}

// Visualization function

fn visualize_n_step_impact(

results: Vec<(usize, HashMap<usize, f64>)>,

output_path: &str,

walk_size: usize,

) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(output_path, (1024, 768)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Impact of n on Learning", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..walk_size as i32, 0.0..1.0)

.unwrap();

chart

.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("State")

.y_desc("Value")

.draw()

.unwrap();

for (n, value_function) in results {