Chapter 9

Policy Gradient Methods

"Policy gradient methods open the door to a new class of algorithms that directly optimize the policy, enabling us to tackle complex problems with continuous actions and high-dimensional spaces." — John Schulman

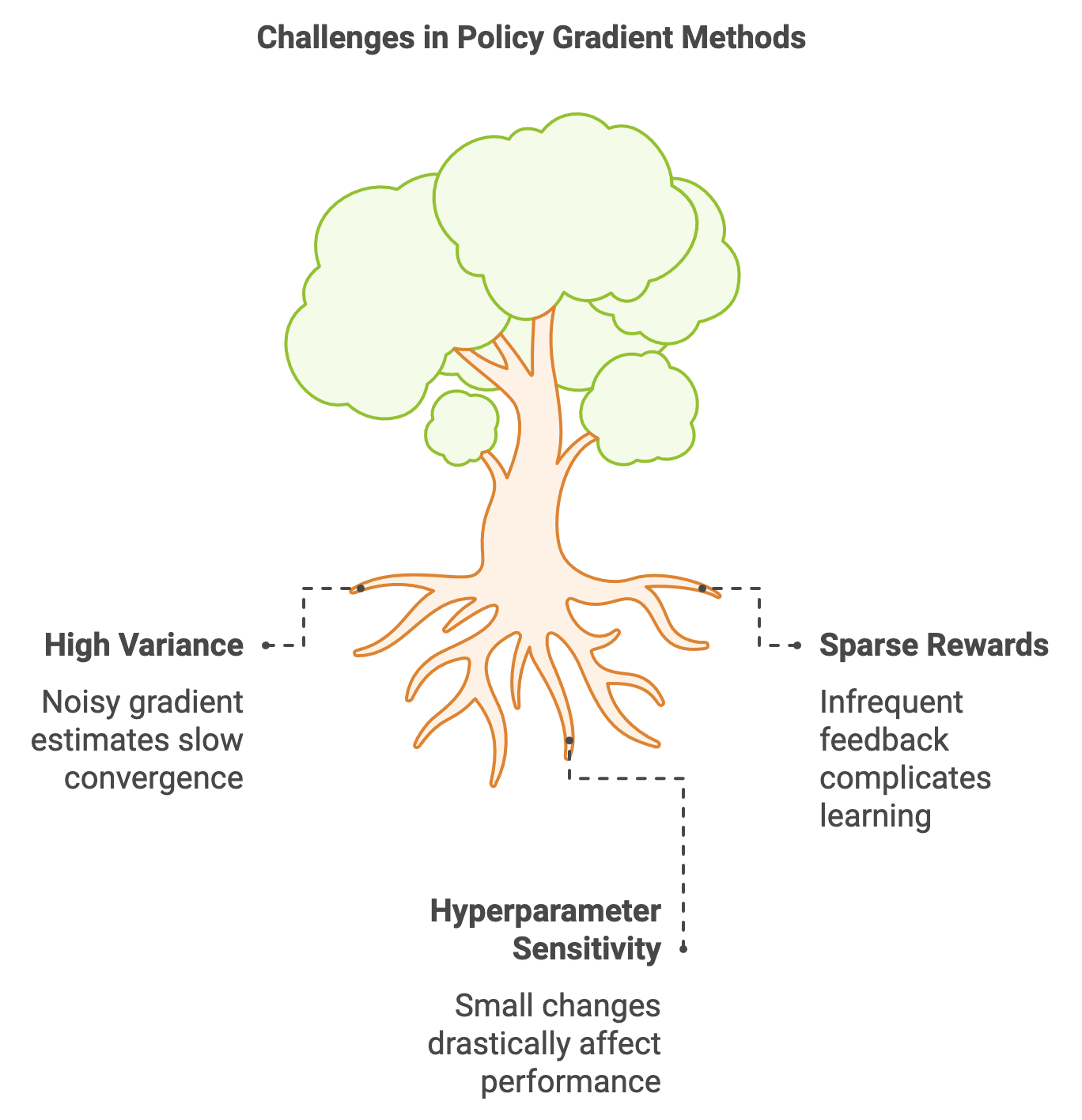

Chapter 9 of RLVR delves into the powerful world of Policy Gradient Methods, a cornerstone of modern reinforcement learning, particularly effective in environments with high-dimensional or continuous action spaces. The chapter begins with an introduction to the core concepts of Policy Gradient Methods, explaining how these methods optimize policies directly by adjusting the parameters that define the policy, leveraging stochastic policies to manage action selection probabilistically. Readers will explore the foundational Policy Gradient Theorem and learn how to implement simple policy gradient methods in Rust, gaining insights into how learning rates and policy parameters affect the learning process. The chapter progresses to the REINFORCE algorithm, a straightforward yet fundamental policy gradient method that utilizes Monte Carlo sampling for gradient estimation, highlighting the importance of variance reduction strategies such as baselines. Moving forward, the chapter introduces Actor-Critic methods, where policy gradients are combined with value function approximation, providing a more stable and efficient learning process. Practical Rust implementations will guide readers through building Actor-Critic models and experimenting with different critic architectures. The chapter then covers advanced methods like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO), which are designed to ensure stable and efficient policy updates, offering a balance between exploration and exploitation. Finally, the chapter addresses the challenges of policy gradient methods, such as high variance and hyperparameter sensitivity, and presents best practices for reducing variance, selecting appropriate baselines, and tuning hyperparameters to achieve stable learning outcomes. Through practical Rust-based simulations, readers will develop a deep understanding of how to apply, optimize, and innovate with policy gradient methods in reinforcement learning.

9.1. Introduction to Policy Gradient Methods

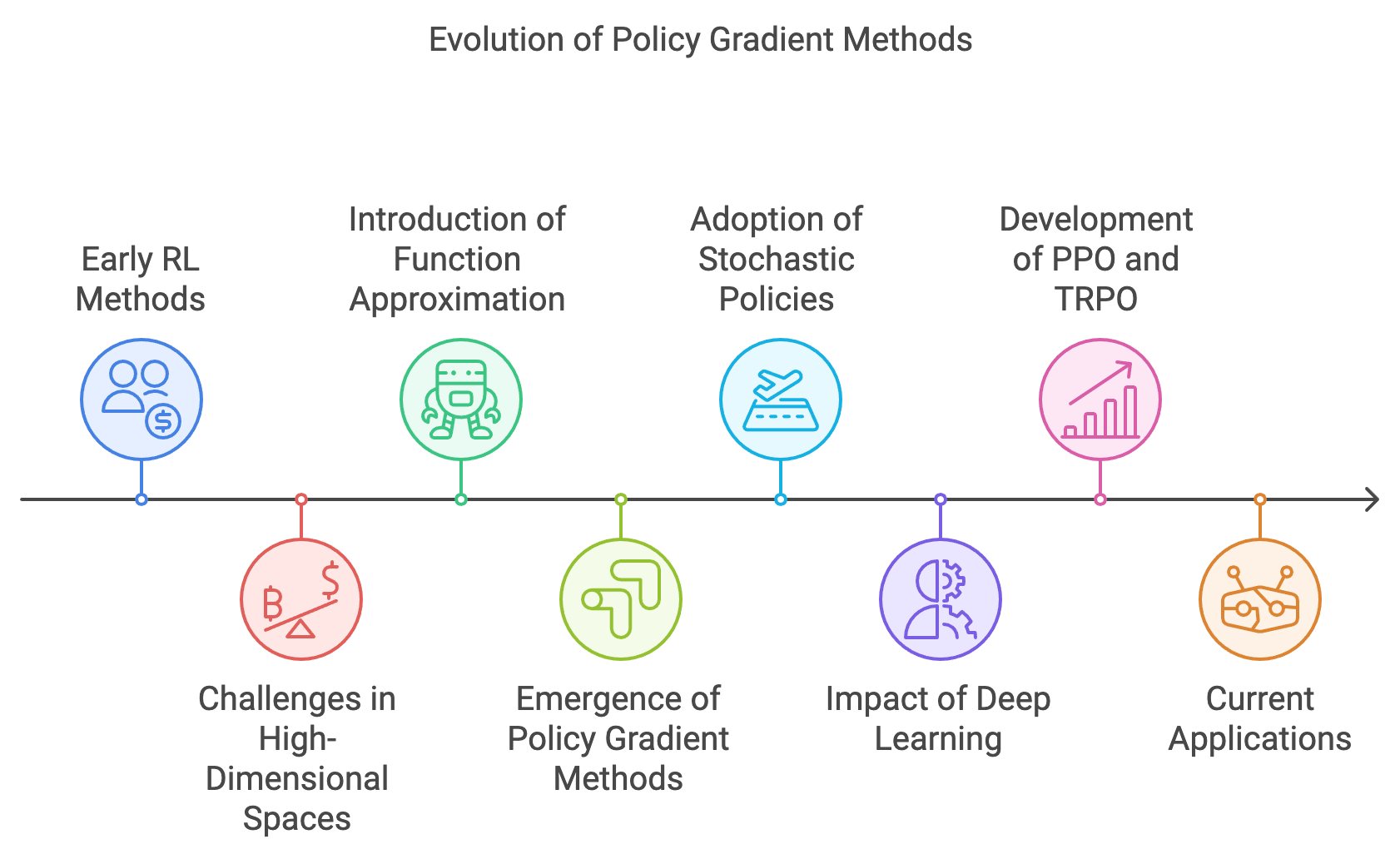

The evolution of policy gradient methods in reinforcement learning reflects the field’s ongoing quest for more efficient and scalable approaches to complex decision-making problems. Early reinforcement learning methods, such as Monte Carlo and Temporal-Difference (TD) learning, primarily focused on estimating value functions to guide policy improvement. While effective in many scenarios, these value-based approaches struggled to address environments with high-dimensional or continuous action spaces. As the complexity of real-world problems grew, so did the need for methods that could directly optimize policies without the intermediate step of estimating value functions. This realization laid the groundwork for the development of policy gradient methods.

Value-based methods, like those explored in Chapters 5 and 6, operate indirectly by optimizing policies through value function estimation. For instance, Q-learning derives a policy by selecting the action with the highest estimated action-value, $Q(s, a)$. While this approach is robust in discrete and structured environments, it becomes computationally infeasible in high-dimensional or continuous action spaces, where accurately estimating value functions for every possible action is impractical. These challenges underscored the need for an alternative paradigm—one that could bypass value function estimation and focus directly on optimizing parameterized policies, especially in environments where action spaces cannot be discretized effectively.

Figure 1: The historical evolution of policy gradient methods in RL.

The introduction of function approximation techniques, as discussed in Chapter 7, marked a significant step forward by extending reinforcement learning to larger state and action spaces. Both linear and non-linear function approximators allowed value functions to generalize across states, reducing computational overhead. However, these techniques were still rooted in the value-based framework, leaving unresolved challenges in environments with continuous or high-dimensional action spaces. This gap created an opportunity for policy gradient methods to emerge, offering a direct and flexible approach to learning policies. Instead of estimating value functions, these methods sought to optimize parameterized policies that map states directly to actions.

Policy gradient methods gained momentum as researchers explored the benefits of stochastic policies, where actions are chosen probabilistically rather than deterministically. This approach offered two major advantages: smoother gradients for optimization and improved exploration capabilities. The REINFORCE algorithm, introduced by Williams in the 1990s, exemplified this paradigm shift. By directly optimizing policy parameters to maximize expected cumulative rewards, REINFORCE provided a simple yet powerful framework for solving high-dimensional decision-making problems. The use of stochastic policies proved particularly advantageous in complex domains like robotics, where actions are continuous and require fine-grained optimization. For instance, a robotic arm navigating a continuous space could use probabilistic policies to adjust its movements iteratively, discovering optimal trajectories more efficiently than deterministic approaches.

The rise of deep learning in the 2010s revolutionized policy gradient methods, enabling them to tackle previously intractable problems. Neural networks provided the expressive power needed to represent complex policies in high-dimensional spaces. Algorithms like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) built upon foundational policy gradient principles while addressing key challenges such as stability and efficiency. These advancements established policy gradient methods as a cornerstone of reinforcement learning, empowering agents to handle high-dimensional and continuous action spaces across domains ranging from robotics to game-playing. Today, policy gradient methods are celebrated for their ability to directly optimize policies, offering a practical and scalable solution to some of the most challenging problems in reinforcement learning.

At the heart of policy gradient methods lies the notion of a stochastic policy. A policy $\pi_\theta(a|s)$ defines the probability of taking action aaa given state $s$, parameterized by $\theta$. Instead of deterministically selecting actions, the policy assigns probabilities to each possible action:

$$ \pi_\theta(a|s) = \frac{\exp(\theta^T \phi(s, a))}{\sum_{a'} \exp(\theta^T \phi(s, a'))}, $$

where $\phi(s, a)$ represents the feature vector for state-action pairs, and $\theta$ are the parameters of the policy.

This probabilistic approach ensures that the agent can explore the action space effectively, balancing exploitation of known good actions with exploration of new possibilities. The inherent randomness in stochastic policies enables smoother updates, avoiding abrupt changes that can destabilize deterministic methods.

The goal of policy gradient methods is to maximize the expected return, defined as the cumulative reward starting from an initial state:

$$J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_t \right],$$

where $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $R_t$ is the reward at time $t$.

To optimize $J(\theta)$, we compute its gradient with respect to the policy parameters:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a|s) Q^\pi(s, a) \right]. $$

This equation is derived from the Policy Gradient Theorem, which provides a mathematically sound method for updating the policy parameters. Intuitively, the gradient points in the direction where the policy can achieve higher expected returns, allowing iterative updates to improve performance.

The Policy Gradient Theorem formalizes how gradients are computed for stochastic policies. It states:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) G_t \right], $$

where $G_t$ is the return from time $t$. This theorem eliminates the need to compute the gradient of the state distribution directly, simplifying the optimization process.

A practical interpretation of this theorem is that we adjust the policy parameters to increase the probability of actions that lead to higher rewards. The term $\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)$ scales the parameter update based on how strongly the current action is encouraged by the policy, weighted by its return.

This Rust program implements a simple policy gradient algorithm to solve a multi-armed bandit problem. The bandit is modeled with three arms, each with a different reward probability. The agent learns a policy that maximizes the expected reward by iteratively updating its parameters based on observed rewards over a series of episodes. The code uses the softmax function to compute action probabilities and updates policy parameters using the policy gradient theorem.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1};

struct Bandit {

arms: usize,

rewards: Vec<f64>,

}

impl Bandit {

fn new(arms: usize, reward_probs: Vec<f64>) -> Self {

Bandit {

arms,

rewards: reward_probs,

}

}

fn pull(&self, arm: usize) -> f64 {

let prob = self.rewards[arm];

if rand::thread_rng().gen::<f64>() < prob {

1.0 // Reward for a successful pull

} else {

0.0 // No reward

}

}

}

fn policy_gradient(

bandit: &Bandit,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut theta = Array1::<f64>::zeros(bandit.arms); // Initialize policy parameters

for _ in 0..episodes {

// Compute policy probabilities using softmax

let exp_theta: Array1<f64> = theta.mapv(|t| t.exp());

let sum_exp_theta = exp_theta.sum();

let policy = &exp_theta / sum_exp_theta;

// Select an action based on the policy

let action = rng.gen_range(0..bandit.arms);

// Get reward for the selected action

let reward = bandit.pull(action);

// Update policy parameters using the policy gradient theorem

for a in 0..bandit.arms {

let grad = if a == action { 1.0 - policy[a] } else { -policy[a] };

theta[a] += alpha * grad * reward;

}

}

theta

}

fn main() {

let bandit = Bandit::new(3, vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]);

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.1;

let theta = policy_gradient(&bandit, episodes, alpha);

println!("Learned Policy Parameters: {:?}", theta);

}

The Bandit struct models a multi-armed bandit with a fixed number of arms and their respective reward probabilities. During training, the agent maintains a set of policy parameters (theta), which determine the probability of selecting each arm through the softmax function. In each episode, the agent selects an action (arm) based on the computed probabilities, observes the reward for that action, and updates the parameters using the policy gradient theorem. This involves increasing the probability of actions that result in rewards while reducing the probabilities of other actions. After 1000 episodes, the learned parameters reflect the optimal policy, which can be derived by applying the softmax function to theta.

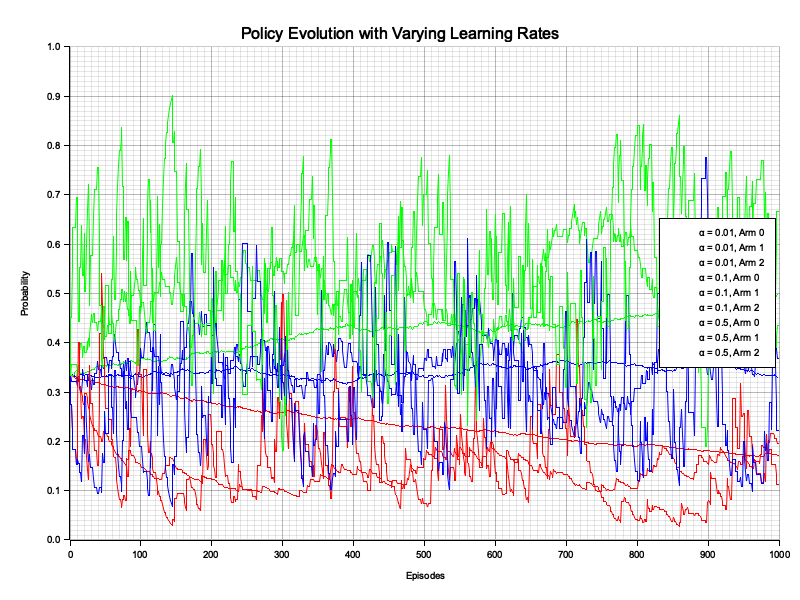

This updated code expands on the initial version by introducing an experiment to evaluate the impact of different learning rates (α) on the evolution of policy probabilities in a multi-armed bandit problem. The agent interacts with a three-armed bandit with reward probabilities of [0.2, 0.5, 0.8] and updates its policy parameters using the policy gradient theorem over 1000 episodes. The experiment tests three learning rates (0.01, 0.1, 0.5) and tracks how the policy probabilities for each arm evolve over time, visualizing the trade-off between convergence speed and stability.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1};

use plotters::prelude::*;

struct Bandit {

arms: usize,

rewards: Vec<f64>,

}

impl Bandit {

fn new(arms: usize, reward_probs: Vec<f64>) -> Self {

Bandit {

arms,

rewards: reward_probs,

}

}

fn pull(&self, arm: usize) -> f64 {

let prob = self.rewards[arm];

if rand::thread_rng().gen::<f64>() < prob {

1.0 // Reward for a successful pull

} else {

0.0 // No reward

}

}

}

fn policy_gradient_with_tracking(

bandit: &Bandit,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

) -> Vec<Array1<f64>> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut theta = Array1::<f64>::zeros(bandit.arms); // Initialize policy parameters

let mut policy_history = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..episodes {

// Compute policy probabilities using softmax

let exp_theta: Array1<f64> = theta.mapv(|t| t.exp());

let sum_exp_theta = exp_theta.sum();

let policy = &exp_theta / sum_exp_theta;

// Store the current policy for visualization

policy_history.push(policy.clone());

// Select an action based on the policy

let action = rng.gen_range(0..bandit.arms);

// Get reward for the selected action

let reward = bandit.pull(action);

// Update policy parameters using the policy gradient theorem

for a in 0..bandit.arms {

let grad = if a == action { 1.0 - policy[a] } else { -policy[a] };

theta[a] += alpha * grad * reward;

}

}

policy_history

}

fn plot_policy_evolution(

policies: Vec<Vec<Array1<f64>>>,

alphas: &[f64],

bandit_arms: usize,

) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new("policy_evolution.png", (800, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Policy Evolution with Varying Learning Rates", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(20)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(50)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..1000, 0.0..1.0) // Ensure x-axis is `i32`

.unwrap();

chart

.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("Episodes")

.y_desc("Probability")

.draw()

.unwrap();

let colors = [RED, BLUE, GREEN, CYAN, MAGENTA, BLACK];

for (alpha_idx, alpha_policies) in policies.iter().enumerate() {

for arm in 0..bandit_arms {

let series: Vec<(i32, f64)> = alpha_policies // Convert usize to i32 for x-axis

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(episode, policy)| (episode as i32, policy[arm]))

.collect();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(series, &colors[arm]))

.unwrap()

.label(format!("α = {}, Arm {}", alphas[alpha_idx], arm));

}

}

chart

.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE)

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()

.unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let bandit = Bandit::new(3, vec![0.2, 0.5, 0.8]);

let episodes = 1000;

let alphas = [0.01, 0.1, 0.5];

let mut policies = Vec::new();

for &alpha in &alphas {

println!("Training with learning rate = {}...", alpha);

let policy_history = policy_gradient_with_tracking(&bandit, episodes, alpha);

policies.push(policy_history);

}

println!("Plotting policy evolution...");

plot_policy_evolution(policies, &alphas, bandit.arms);

println!("Plot saved as 'policy_evolution.png'.");

}

The bandit environment allows the agent to select one of the three arms in each episode, with the reward probability for each arm defined at initialization. The policy_gradient_with_tracking function trains the agent by computing action probabilities using a softmax function, selecting an arm probabilistically, and updating the policy parameters (theta) based on the observed reward. The function tracks the policy probabilities for each arm at every episode. The plot_policy_evolution function visualizes these probabilities for each arm and learning rate, showing how the agent's behavior changes over time as it learns the optimal policy.

Figure 2: Policy evolution with learning rate for multi-armed bandit.

The visualization reveals how the learning rate affects the agent's ability to learn a policy that favors the optimal arm (Arm 2 with a reward probability of 0.8). A low learning rate (α = 0.01) results in slow but stable convergence, with the probabilities gradually favoring the optimal arm. A moderate learning rate (α = 0.1) balances speed and stability, achieving a clear preference for the optimal arm more quickly. A high learning rate (α = 0.5) leads to faster updates but introduces significant instability, causing the probabilities to fluctuate heavily before stabilizing. This highlights the trade-off: smaller learning rates improve stability but slow convergence, while larger learning rates accelerate learning at the risk of instability. The medium learning rate (α = 0.1) provides the best balance in this scenario.

This section provides a rigorous introduction to policy gradient methods, blending theoretical insights with practical implementations in Rust. The combination of mathematical foundations, conceptual understanding, and hands-on coding equips readers with the skills to apply policy gradient methods effectively in reinforcement learning tasks.

9.2. REINFORCE Algorithm

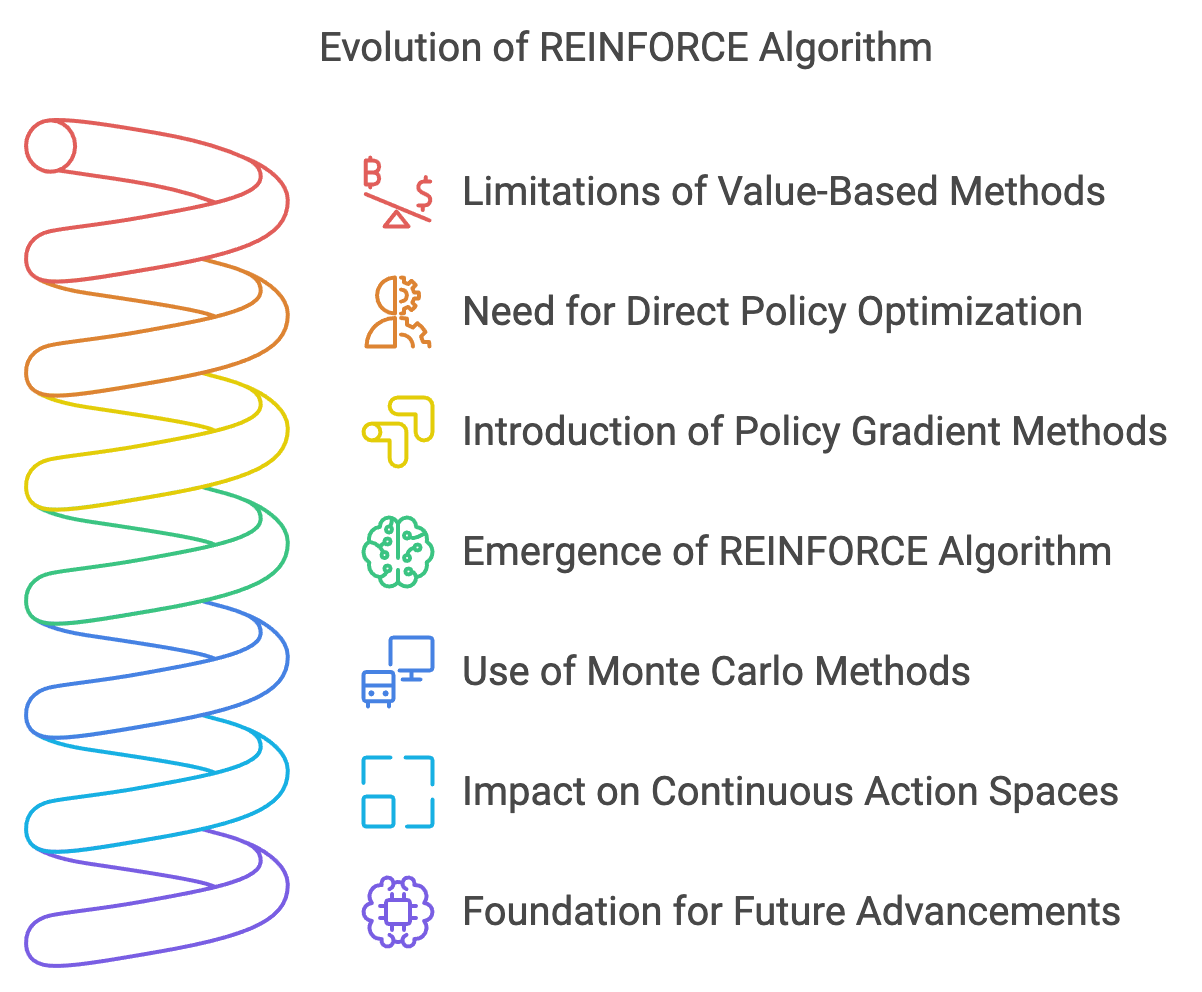

The REINFORCE algorithm was born out of the pressing need to overcome the limitations of value-based reinforcement learning methods and establish a more direct approach to optimizing policies. Value-based methods, such as Q-learning and SARSA, rely on estimating value functions as an intermediary step to derive policies. While these methods have been highly effective in discrete and well-structured environments, they encounter significant scalability issues in high-dimensional or continuous action spaces. In such environments, accurately estimating value functions for every possible state-action pair becomes computationally prohibitive, especially as the action space grows exponentially or is inherently continuous. The inefficiencies associated with discretizing continuous action spaces further exacerbate the problem, often leading to poor performance and infeasible computational demands.

Figure 3: Historical evolution of REINFORCE algorithm.

The limitations of value-based methods highlighted the need for a paradigm shift toward direct policy optimization. Policy gradient methods provided a compelling solution by parameterizing policies and optimizing them directly, without the intermediate step of value function estimation. This approach offered several advantages, particularly in environments with continuous action spaces, such as robotic control tasks, where actions are best represented as continuous variables rather than discrete choices. Direct optimization of parameterized policies not only addressed the scalability issues but also opened new avenues for incorporating stochasticity into policies. The probabilistic nature of stochastic policies facilitated better exploration of the action space, ensuring smoother optimization and reducing the risk of convergence to suboptimal deterministic strategies.

The REINFORCE algorithm emerged as a seminal formalization of this direct optimization framework. By leveraging the simplicity of Monte Carlo methods, REINFORCE estimates the gradient of the policy objective function based on sampled episodes of interaction with the environment. This enables agents to optimize policies by directly maximizing cumulative rewards, without the need for explicit value function approximations. The Monte Carlo nature of the algorithm ensures unbiased estimates of the policy gradient, albeit with high variance, making it particularly suited for episodic tasks where trajectories can be sampled in their entirety.

As one of the earliest and most influential policy gradient methods, REINFORCE demonstrated the potential of direct policy optimization in reinforcement learning. Its ability to tackle high-dimensional and continuous action spaces effectively laid the groundwork for future advancements, including the integration of policy gradient techniques with deep learning architectures. The algorithm remains a foundational tool, showcasing the power and elegance of policy gradient methods in addressing complex reinforcement learning challenges.

At its core, REINFORCE updates the policy parameters $\theta$ by maximizing the expected return:

$$ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_t \right], $$

where $\pi_\theta$ represents the policy parameterized by $\theta$, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $R_t$ is the reward at time $t$. The algorithm leverages the policy gradient theorem to compute updates:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) G_t \right], $$

where $G_t$ is the total return starting at time $t$.

REINFORCE is designed for episodic tasks, where the agent interacts with the environment in discrete episodes, each ending in a terminal state. After completing an episode, the algorithm updates the policy based on the total return $G_t$ for each state-action pair observed during the episode. This approach simplifies the implementation, as it does not require bootstrapping from value functions like TD methods.

An analogy can help clarify this concept: Imagine teaching a student by observing their performance over an entire exam (the episode) and then providing feedback at the end. This feedback is based on the overall outcome, rather than intermediate answers.

A significant challenge in REINFORCE is the high variance of its gradient estimates, which can lead to unstable learning. To mitigate this, a baseline is introduced. The baseline does not change the expected value of the gradient but reduces its variance, improving the stability and efficiency of learning. The gradient with a baseline $b(s)$ is given by:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) (G_t - b(s_t)) \right]. $$

Common choices for the baseline include the average return, a learned value function, or a constant value. Using a baseline is akin to providing more specific feedback by comparing performance to an expected standard, enabling the agent to focus on relative improvements.

The variance of policy gradient estimates is a critical factor in the performance of the REINFORCE algorithm. High variance can cause erratic updates, slowing convergence or destabilizing the learning process. By subtracting a baseline, we effectively remove irrelevant fluctuations in the return, focusing updates on meaningful differences.

Balancing bias and variance is crucial when choosing a baseline. A well-chosen baseline minimizes variance without introducing significant bias, leading to faster and more stable learning. This trade-off is analogous to teaching by giving constructive feedback: too general feedback (high variance) may confuse the student, while overly specific feedback (high bias) may misguide them.

REINFORCE serves as a foundation for more advanced policy gradient methods. While its reliance on episodic updates and high-variance estimates can be limiting, these challenges have inspired enhancements such as actor-critic methods, which combine policy gradients with value-based updates to improve efficiency and stability. Understanding REINFORCE provides a solid basis for exploring these advanced algorithms.

This Rust program implements the REINFORCE algorithm with baselines to train a policy for a simplified CartPole environment. The CartPole environment simulates an agent balancing a pole on a cart, represented as a 4-dimensional state vector. The policy is parameterized using a matrix (theta) that maps state features to action probabilities, updated via policy gradient calculations. The goal is to maximize cumulative rewards through episodic interactions, leveraging the REINFORCE algorithm to adjust the policy.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use std::f64::consts::E;

struct CartPoleEnv;

impl CartPoleEnv {

fn step(&self, state: Array1<f64>, _action: usize) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

// Simulate environment dynamics with random noise

let next_state = state.mapv(|x| x + (rand::random::<f64>() - 0.5) * 0.1);

let reward = if next_state[0].abs() < 2.0 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 };

let done = reward == 0.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

Array1::zeros(4) // Reset to initial state (zeroed state vector)

}

}

fn softmax(policy: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let exp_policy = policy.mapv(|x| E.powf(x));

&exp_policy / exp_policy.sum()

}

fn reinforce(env: &CartPoleEnv, episodes: usize, alpha: f64, gamma: f64) {

let mut theta = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 2)); // Policy parameters (state features x actions)

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut states = Vec::new();

let mut actions = Vec::new();

let mut rewards = Vec::new();

let mut action_probs = Vec::new(); // Store probabilities for each action

// Generate an episode

let mut state = env.reset();

while states.len() < 100 {

states.push(state.clone());

let logits = theta.t().dot(&state);

let probabilities = softmax(&logits);

action_probs.push(probabilities.clone());

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < probabilities[0] { 0 } else { 1 };

actions.push(action);

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(state.clone(), action);

rewards.push(reward);

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

// Compute returns

let mut returns = vec![0.0; rewards.len()];

let mut cumulative = 0.0;

for t in (0..rewards.len()).rev() {

cumulative = rewards[t] + gamma * cumulative;

returns[t] = cumulative;

}

// Update policy

for t in 0..states.len() {

let state = &states[t];

let action = actions[t];

let probabilities = &action_probs[t];

let baseline = returns.iter().sum::<f64>() / returns.len() as f64; // Baseline as average return

let mut grad = Array1::zeros(2);

grad[action] = 1.0 - probabilities[action];

for a in 0..2 {

if a != action {

grad[a] = -probabilities[a];

}

}

// Create a separate owned value for grad_outer

let grad_outer = grad

.insert_axis(ndarray::Axis(1))

.dot(&state.clone().insert_axis(ndarray::Axis(0)))

.t()

.to_owned(); // Convert to owned Array2 immediately

// Now use the owned grad_outer

theta += &(grad_outer * alpha * (returns[t] - baseline));

}

}

}

fn main() {

let env = CartPoleEnv;

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.01;

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Training REINFORCE with baseline...");

reinforce(&env, episodes, alpha, gamma);

println!("Training REINFORCE without baseline...");

reinforce(&env, episodes, alpha, gamma);

}

The CartPoleEnv provides the environment's dynamics, including the step function, which advances the state based on the agent's actions, and reset, which initializes the state. The softmax function computes action probabilities from policy logits. In the reinforce function, the agent generates episodes by sampling actions from the policy and collecting rewards. It computes cumulative returns for each step in the episode, using a discount factor (gamma). The policy is updated using the REINFORCE gradient, where a baseline (average return) is subtracted to reduce variance. Gradients are computed for each action and used to adjust the policy parameters (theta). The outer product of the gradient and state is calculated and applied to update theta, ensuring shapes align with the policy matrix. Training runs for a specified number of episodes to optimize the policy.

In this updated version, the code implements an experiment to compare the REINFORCE algorithm with and without baselines for training a policy on a simulated CartPole environment. The baseline strategy used here is the average return across an episode, which helps reduce the variance of the policy gradient updates. By comparing the total rewards over episodes, the experiment aims to analyze the impact of the baseline on learning stability and performance. The cumulative rewards for both strategies are tracked and visualized to highlight their differences.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::f64::consts::E;

struct CartPoleEnv;

impl CartPoleEnv {

fn step(&self, state: Array1<f64>, _action: usize) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let next_state = state.mapv(|x| x + (rand::random::<f64>() - 0.5) * 0.1);

let reward = if next_state[0].abs() < 2.0 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 };

let done = reward == 0.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

Array1::zeros(4)

}

}

fn softmax(policy: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let exp_policy = policy.mapv(|x| E.powf(x));

&exp_policy / exp_policy.sum()

}

fn reinforce(

env: &CartPoleEnv,

episodes: usize,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

use_baseline: bool,

) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut theta = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 2));

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut cumulative_rewards = Vec::new();

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut states = Vec::new();

let mut actions = Vec::new();

let mut rewards = Vec::new();

let mut action_probs = Vec::new();

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut episode_reward = 0.0;

while states.len() < 100 {

states.push(state.clone());

let logits = theta.t().dot(&state);

let probabilities = softmax(&logits);

action_probs.push(probabilities.clone());

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < probabilities[0] { 0 } else { 1 };

actions.push(action);

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(state.clone(), action);

rewards.push(reward);

episode_reward += reward;

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

cumulative_rewards.push(episode_reward); // Track total rewards

if episode % 100 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {}", episode, episode_reward);

}

let mut returns = vec![0.0; rewards.len()];

let mut cumulative = 0.0;

for t in (0..rewards.len()).rev() {

cumulative = rewards[t] + gamma * cumulative;

returns[t] = cumulative;

}

for t in 0..states.len() {

let state = &states[t];

let action = actions[t];

let probabilities = &action_probs[t];

let baseline = if use_baseline {

returns.iter().sum::<f64>() / returns.len() as f64

} else {

0.0

};

let mut grad = Array1::zeros(2);

grad[action] = 1.0 - probabilities[action];

for a in 0..2 {

if a != action {

grad[a] = -probabilities[a];

}

}

let grad_outer = grad

.insert_axis(ndarray::Axis(1))

.dot(&state.clone().insert_axis(ndarray::Axis(0)))

.t()

.to_owned();

theta += &(grad_outer * alpha * (returns[t] - baseline));

}

}

println!("Final Cumulative Rewards: {:?}", cumulative_rewards); // Debug cumulative rewards

cumulative_rewards

}

fn plot_rewards(rewards: Vec<Vec<f64>>, labels: &[&str], episodes: usize) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new("baseline_comparison_debugged.png", (800, 600))

.into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let max_reward = rewards

.iter()

.flat_map(|v| v.iter())

.cloned()

.fold(0.0 / 0.0, f64::max); // Dynamically find the max reward

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Baseline Strategies Comparison", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(20)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(50)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..episodes, 0.0..max_reward)

.unwrap();

chart

.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("Episodes")

.y_desc("Total Reward")

.draw()

.unwrap();

let colors = [RED, BLUE];

for (i, reward) in rewards.iter().enumerate() {

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

reward.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&colors[i],

))

.unwrap()

.label(labels[i])

.legend(move |(x, y)| PathElement::new([(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &colors[i]));

}

chart

.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE)

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()

.unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let env = CartPoleEnv;

let episodes = 1000;

let alpha = 0.01;

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Training REINFORCE with baseline...");

let rewards_with_baseline = reinforce(&env, episodes, alpha, gamma, true);

println!("Training REINFORCE without baseline...");

let rewards_without_baseline = reinforce(&env, episodes, alpha, gamma, false);

println!("Plotting results...");

plot_rewards(

vec![rewards_with_baseline, rewards_without_baseline],

&["With Baseline", "Without Baseline"],

episodes,

);

println!("Plot saved as 'baseline_comparison_debugged.png'.");

}

The reinforce function runs the REINFORCE algorithm for a given number of episodes. It generates episodes by sampling actions from a softmax-based policy and collecting rewards. Cumulative returns are calculated using a discount factor (gamma) for each step. Depending on the use_baseline parameter, the algorithm either uses the average return as a baseline to reduce variance or skips the baseline entirely. The policy parameters (theta) are updated using the policy gradient, computed as the outer product of the gradient and the state. Finally, cumulative rewards for each episode are returned. The plot_rewards function uses plotters to visualize the total rewards over episodes for both strategies, enabling direct comparison of their performance. The visualization (baseline_comparison_debugged.png) should show two reward curves over episodes:

With Baseline: This curve is expected to be smoother due to the reduced variance in updates. Using a baseline minimizes the stochasticity caused by reward variations, leading to more stable learning.

Without Baseline: This curve might exhibit higher variance but could converge faster in some cases. The lack of variance reduction makes the updates more sensitive to episodic rewards, resulting in greater fluctuations.

The experiment highlights the trade-offs between bias and variance. While the baseline reduces variance and improves stability, it can sometimes introduce a slight bias that affects convergence speed. This analysis reinforces the importance of baseline strategies in policy gradient methods for achieving efficient and stable learning.

This section combines a comprehensive theoretical foundation with practical implementations in Rust. By exploring the REINFORCE algorithm and its variants, readers gain a deep understanding of policy gradient methods and their role in reinforcement learning.

9.3. Actor-Critic Methods

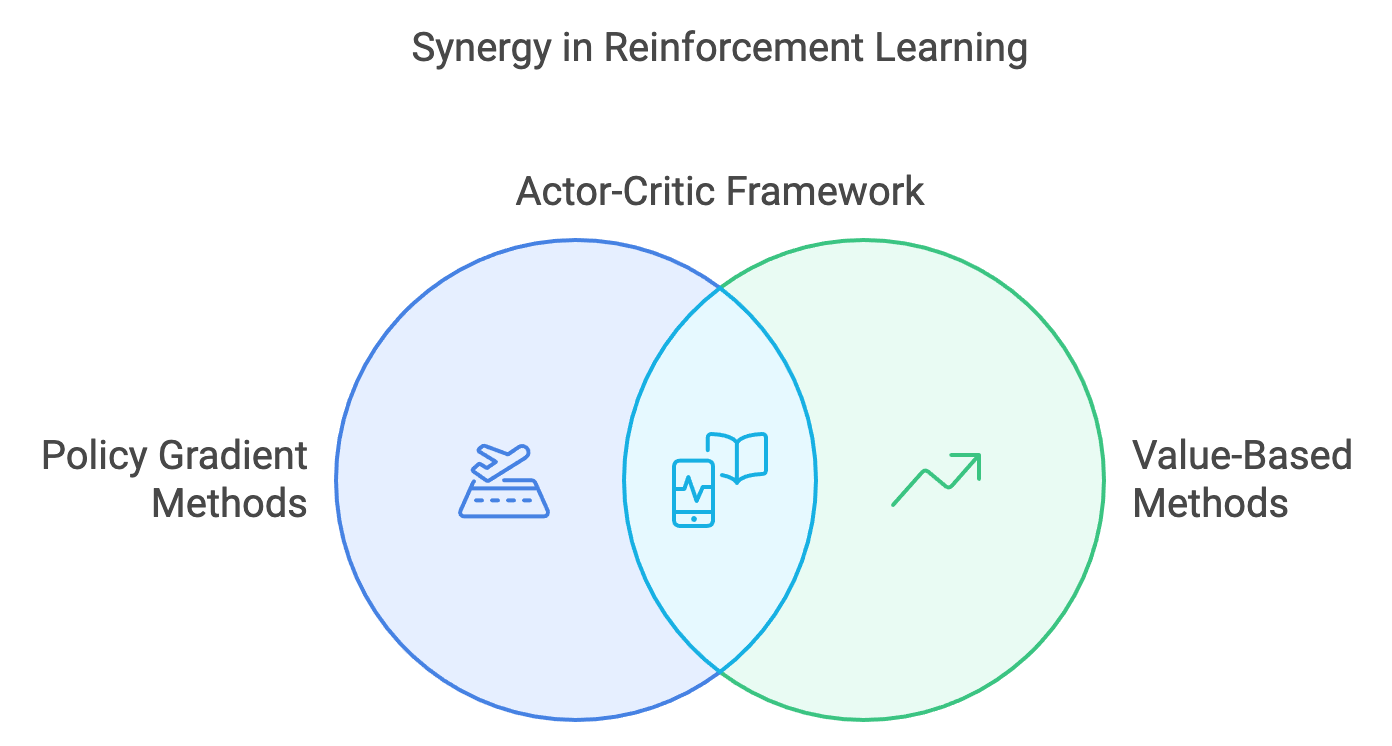

The Actor-Critic framework in reinforcement learning was developed to address the limitations of both policy gradient methods, such as REINFORCE, and traditional value-based approaches, such as Q-learning. Policy gradient methods optimize the policy directly, offering a natural solution for environments with high-dimensional or continuous action spaces. However, these methods often suffer from high variance in their gradient estimates, leading to slow convergence and unstable learning. On the other hand, value-based methods excel at leveraging value functions to reduce variance in updates but struggle to scale effectively in environments with complex action spaces, where discretization is impractical.

Figure 4: Policy gradient, value-based and actor-critic synergy.

Actor-Critic algorithms emerged as a hybrid solution that merges the strengths of these two paradigms. By introducing two distinct components—the actor and the critic—these methods achieve a synergy that addresses the weaknesses of their individual counterparts. The actor represents the policy, parameterized as $\pi_\theta(a|s)$, where $\theta$ denotes the policy parameters. The actor’s role is to determine the actions the agent should take to maximize cumulative rewards. Meanwhile, the critic evaluates the quality of the actor’s decisions by estimating a value function, such as the state-value function $V_w(s)$, parameterized by $w$. This dual mechanism allows the actor to benefit from the critic’s feedback, reducing the variance of policy gradient updates and accelerating convergence.

The key motivation behind Actor-Critic methods is their ability to combine the low-variance learning dynamics of value-based approaches with the flexibility and scalability of policy gradient methods. The critic’s role as a value estimator stabilizes the learning process by providing more grounded feedback to the actor, reducing the noise inherent in Monte Carlo policy gradient methods like REINFORCE. At the same time, the actor retains the ability to optimize policies directly, making it suitable for tasks involving continuous or high-dimensional action spaces, where value-based methods falter. This combination creates a balance between exploration and stability, allowing Actor-Critic algorithms to tackle more complex and dynamic environments.

Actor-Critic methods are particularly well-suited for environments requiring continuous control, such as robotic manipulation, autonomous vehicles, and physics-based simulations. In such domains, the actor can leverage stochastic policies to explore the action space efficiently, while the critic guides the actor toward more rewarding behaviors by providing a smoothed estimate of expected returns. This synergy is not only effective for handling high-dimensional problems but also makes Actor-Critic algorithms highly adaptable to real-world challenges, where noise and uncertainty are prevalent.

The development of Actor-Critic methods has had a profound impact on the field of reinforcement learning, inspiring a variety of advanced algorithms. Techniques such as Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) extend the Actor-Critic framework, introducing enhancements like better variance reduction, stability in updates, and scalability in distributed environments. These advancements underscore the foundational role of Actor-Critic methods in modern reinforcement learning and their versatility in addressing complex decision-making tasks.

Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) is an enhancement of the basic Actor-Critic framework that aims to improve the stability and efficiency of policy updates by incorporating the advantage function into the learning process. The advantage function measures the relative quality of a chosen action compared to the average performance of actions in a given state. This distinction helps reduce variance in gradient updates, as it focuses the actor’s learning on actions that are truly better than average, rather than on all actions indiscriminately. A2C also adopts a synchronous, multi-worker approach, where multiple environments are run in parallel to collect trajectories, allowing for faster and more stable learning. This makes A2C particularly effective in tasks requiring large-scale exploration and frequent updates.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) builds upon the Actor-Critic framework by introducing a more stable and efficient way to update policies. PPO employs a clipped objective function that restricts large changes to the policy during updates, ensuring gradual and controlled improvement. This method mitigates the instability often caused by drastic policy updates, which can lead to divergence in traditional Actor-Critic algorithms. PPO strikes a balance between simplicity and performance by avoiding the computational overhead of complex optimization constraints like those used in Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO). Its ease of implementation, combined with robustness, has made PPO one of the most popular reinforcement learning algorithms, widely applied in domains such as robotics, game playing, and simulated environments.

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) extends the Actor-Critic framework to deterministic policies, specifically designed for continuous action spaces. Unlike stochastic policies used in traditional Actor-Critic methods, DDPG employs a deterministic policy that maps states directly to actions. This approach reduces the complexity of policy evaluation and improves learning efficiency in environments where deterministic actions suffice. DDPG leverages an off-policy learning framework, using a replay buffer to store and reuse past experiences, and a target network to stabilize updates. These features help mitigate instability and variance in training. DDPG is particularly suited for tasks like robotic control and autonomous systems, where precise, continuous action outputs are crucial.

The actor updates the policy parameters using the gradient of the policy objective:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a|s) A(s, a) \right], $$

where $A(s, a)$ is the advantage function, which quantifies how much better an action $a$ is compared to the expected value of the state $s$. The advantage function is typically defined as:

$$ A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s), $$

where $Q(s, a)$ is the action-value function, and $V(s)$ is the state-value function.

The critic evaluates the actor’s performance by estimating $V(s)$ using temporal difference (TD) learning:

$$ \delta_t = R_{t+1} + \gamma V_w(S_{t+1}) - V_w(S_t), $$

where $\delta_t$ is the TD error. This error serves as feedback for both the actor and the critic: the actor uses it to improve the policy, and the critic uses it to refine the value function estimate.

TD learning plays a central role in actor-critic methods, offering an efficient way to estimate value functions without waiting for an entire episode to complete, as in Monte Carlo methods. By updating the value function incrementally using the TD error, actor-critic methods achieve faster learning and greater stability.

An analogy can clarify this: imagine a coach (critic) guiding an athlete (actor). Instead of waiting until the end of a competition to provide feedback, the coach gives real-time corrections (TD error) to refine the athlete's actions during the event.

The advantage function is a crucial component in reducing the variance of policy gradient estimates. By focusing on the relative benefit of actions, the advantage function refines updates to the policy. Instead of optimizing based on absolute returns, which can be noisy, the advantage function centers updates around the baseline provided by the value function $V(s)$. This reduces the impact of outliers and ensures more stable learning.

The following implementation demonstrates a basic actor-critic algorithm applied to a robotic arm control task. The actor is represented by a policy network, and the critic is a value function approximator. The algorithm uses TD learning to update the critic and policy gradients to update the actor. The actor-critic model implemented in this code is RL algorithm that combines the strengths of policy-based and value-based methods. The model consists of two key components: the actor, which determines the policy by mapping states to a probability distribution over actions, and the critic, which evaluates the quality of the actions taken by estimating the value function. This implementation uses a robot arm environment where an agent learns to optimize its actions based on the feedback (rewards) it receives from interacting with the environment. By continuously updating the actor's policy parameters and the critic's value function, the model aims to maximize the cumulative rewards over a series of episodes.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, arr1};

use std::collections::HashMap;

// Custom hash function for floating-point arrays

fn hash_f64_vec(vec: &[f64]) -> u64 {

use std::collections::hash_map::DefaultHasher;

use std::hash::{Hash, Hasher};

let mut hasher = DefaultHasher::new();

vec.len().hash(&mut hasher);

for &val in vec {

val.to_bits().hash(&mut hasher);

}

hasher.finish()

}

// Wrapper struct with custom equality and hash

#[derive(Clone)]

struct StateKey(Vec<f64>);

impl PartialEq for StateKey {

fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

self.0.len() == other.0.len() &&

self.0.iter().zip(&other.0).all(|(a, b)| a.to_bits() == b.to_bits())

}

}

impl Eq for StateKey {}

impl std::hash::Hash for StateKey {

fn hash<H: std::hash::Hasher>(&self, state: &mut H) {

hash_f64_vec(&self.0).hash(state);

}

}

fn actor_critic(

env: &RobotArmEnv,

episodes: usize,

alpha_actor: f64,

alpha_critic: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (Array2<f64>, HashMap<StateKey, f64>) {

let mut actor_params = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 2)); // Actor parameters (state features x actions)

let mut critic_params: HashMap<StateKey, f64> = HashMap::new(); // Critic values

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

loop {

// Compute policy probabilities using softmax

let logits = actor_params.t().dot(&state);

let probabilities = softmax(&logits);

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < probabilities[0] { 0 } else { 1 };

// Take a step in the environment

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(state.clone(), action);

// Wrap states for HashMap

let state_key = StateKey(state.to_vec());

let next_state_key = StateKey(next_state.to_vec());

// TD Error

let v_current = *critic_params.get(&state_key).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let v_next = *critic_params.get(&next_state_key).unwrap_or(&0.0);

let td_error = reward + gamma * v_next - v_current;

// Update critic

critic_params

.entry(state_key.clone())

.and_modify(|v| *v += alpha_critic * td_error)

.or_insert(alpha_critic * td_error);

// Update actor

let grad = arr1(&[

if action == 0 { probabilities[0] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[0] },

if action == 1 { probabilities[1] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[1] }

]);

// Compute outer product and transpose to match actor_params shape

let grad_outer = grad

.to_shape((2, 1)).unwrap()

.dot(&state.to_shape((1, 4)).unwrap())

.t()

.to_owned(); // Convert to owned array

// Perform element-wise addition using `.zip_mut_with()`

actor_params.zip_mut_with(&grad_outer, |param, grad| {

*param += grad * alpha_actor * td_error;

});

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

}

(actor_params, critic_params)

}

struct RobotArmEnv;

impl RobotArmEnv {

fn step(&self, state: Array1<f64>, _action: usize) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let next_state = state.mapv(|x| x + (rng.gen::<f64>() - 0.5) * 0.1);

let reward = if next_state[0].abs() < 2.0 { 1.0 } else { -1.0 };

let done = reward == -1.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

arr1(&[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]) // Reset to initial state

}

}

fn softmax(policy: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let exp_policy = policy.mapv(f64::exp);

&exp_policy / exp_policy.sum()

}

fn main() {

let env = RobotArmEnv;

let episodes = 500;

let alpha_actor = 0.01;

let alpha_critic = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Training Actor-Critic...");

let (actor_params, _critic_params) = actor_critic(&env, episodes, alpha_actor, alpha_critic, gamma);

println!("Trained Actor Parameters: {:?}", actor_params);

}

The actor-critic algorithm begins by initializing the actor's policy parameters (a matrix mapping states to actions) and the critic's value function (stored in a hash map). In each episode, the agent starts in an initial state and repeatedly selects actions using the actor's policy, computed via the softmax of the policy parameters. The chosen action is executed in the environment, transitioning the agent to a new state and producing a reward. The critic calculates the temporal difference (TD) error, which represents the difference between the predicted value of the current state and the updated estimate using the next state's value. This TD error is then used to update the critic's value function and the actor's policy parameters. The actor's parameters are updated using the gradient of the policy, scaled by the TD error, which ensures that actions leading to higher rewards are more likely to be chosen in the future. This iterative process balances exploration and exploitation, gradually improving both the policy and the value function over many episodes.

Compared to the previous code, this experiment replaces the hash map critic with a linear function approximator as the value function. This allows the exploration of how different critic architectures affect the learning process of the actor-critic algorithm. The experiment specifically focuses on the trade-offs between the simplicity and efficiency of a linear critic versus the flexibility of a hash map. By tracking cumulative rewards over episodes, the experiment demonstrates the performance of the actor-critic algorithm with a linear critic in a continuous state environment (robot arm simulation). The visualization provides a clear picture of how rewards evolve as the model learns.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, arr1};

use plotters::prelude::*;

struct LinearCritic {

weights: Array1<f64>,

}

impl LinearCritic {

fn new(state_dim: usize) -> Self {

Self {

weights: Array1::zeros(state_dim),

}

}

fn predict(&self, state: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

self.weights.dot(state)

}

fn update(&mut self, state: &Array1<f64>, td_error: f64, alpha: f64) {

self.weights += &(state * (alpha * td_error));

}

}

fn actor_critic(

env: &RobotArmEnv,

episodes: usize,

alpha_actor: f64,

alpha_critic: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (Array2<f64>, Vec<f64>) {

let mut actor_params = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 2)); // Actor parameters (state features x actions)

let mut critic = LinearCritic::new(4); // Linear critic

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut cumulative_rewards = Vec::new();

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut episode_reward = 0.0;

loop {

// Compute policy probabilities using softmax

let logits = actor_params.t().dot(&state);

let probabilities = softmax(&logits);

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < probabilities[0] { 0 } else { 1 };

// Take a step in the environment

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(&state, action);

episode_reward += reward;

// TD Error

let v_current = critic.predict(&state);

let v_next = if done { 0.0 } else { critic.predict(&next_state) };

let td_error = reward + gamma * v_next - v_current;

// Update critic

critic.update(&state, td_error, alpha_critic);

// Update actor

let grad = arr1(&[

if action == 0 { probabilities[0] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[0] },

if action == 1 { probabilities[1] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[1] }

]);

// Compute gradient outer product

let grad_outer = grad

.to_shape((2, 1)).unwrap()

.dot(&state.to_shape((1, 4)).unwrap())

.t()

.to_owned();

// Element-wise update for actor parameters

actor_params.zip_mut_with(&grad_outer, |param, &grad| {

*param += grad * alpha_actor * td_error;

});

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

cumulative_rewards.push(episode_reward);

if episode % 50 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {}", episode, episode_reward);

}

}

(actor_params, cumulative_rewards)

}

struct RobotArmEnv;

impl RobotArmEnv {

fn step(&self, state: &Array1<f64>, _action: usize) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let next_state = state.mapv(|x| x + (rng.gen::<f64>() - 0.5) * 0.1);

let reward = if next_state[0].abs() < 2.0 { 1.0 } else { -1.0 };

let done = reward == -1.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

arr1(&[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]) // Reset to initial state

}

}

fn softmax(policy: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let exp_policy = policy.mapv(f64::exp);

&exp_policy / exp_policy.sum()

}

fn plot_rewards(rewards: Vec<f64>, episodes: usize) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new("critic_architectures.png", (800, 600))

.into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let max_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Rewards Over Episodes", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(20)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(50)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..episodes, 0.0..max_reward)

.unwrap();

chart

.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("Episodes")

.y_desc("Total Reward")

.draw()

.unwrap();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&RED,

))

.unwrap()

.label("Total Rewards")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new([(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &RED));

chart

.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE)

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()

.unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let env = RobotArmEnv;

let episodes = 500;

let alpha_actor = 0.01;

let alpha_critic = 0.1;

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Training Actor-Critic...");

let (_, rewards_linear_critic) = actor_critic(&env, episodes, alpha_actor, alpha_critic, gamma);

println!("Plotting results...");

plot_rewards(rewards_linear_critic, episodes);

println!("Plot saved as 'critic_architectures.png'.");

}

The code defines a LinearCritic struct that approximates the value function using a linear model, where the weights are updated via gradient descent based on the temporal difference (TD) error. The actor_critic function initializes the actor parameters as a 4x2 matrix and uses the linear critic to estimate the value of each state. The policy is calculated using the softmax of the actor parameters, and actions are sampled based on the policy's probabilities. During each episode, the actor is updated using the policy gradient scaled by the TD error, and the critic's weights are updated to minimize the TD error. Cumulative rewards are tracked over episodes and visualized using the plotters library.

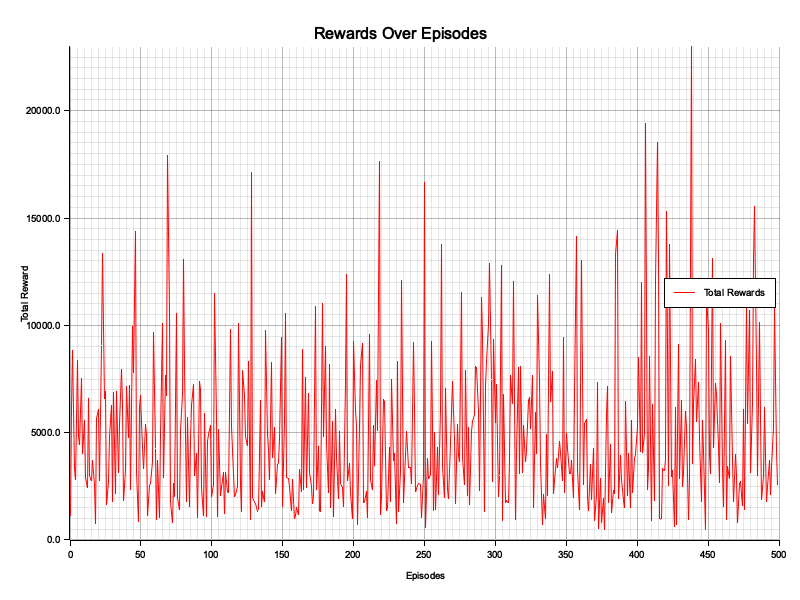

Figure 5: Plotters visualization of rewards vs episode.

The chart "Rewards Over Episodes" illustrates the total rewards accumulated in each episode during the training of the actor-critic model. The significant fluctuations in rewards indicate high variance, reflecting the model's instability in learning and adapting to the environment. The lack of a clear upward trend suggests that the actor-critic algorithm struggles to systematically improve its performance, potentially due to limitations of the linear critic in accurately approximating the value function or suboptimal hyperparameters such as learning rates. Occasional spikes in rewards indicate moments of success but are inconsistent, highlighting the need for better exploration strategies or enhancements to the critic's architecture, such as using a neural network. Overall, the chart underscores the challenges faced by the current setup and points to areas where the model could be refined for more stable and effective learning.

Compared to the previous implementation, this code introduces a neural network-based critic using the tch library instead of the earlier hash map-based approach. The neural critic allows for more generalizable and flexible value function approximation. It uses a small feedforward network with one hidden layer and ReLU activation, offering better modeling capacity for complex environments. Additionally, the code ensures compatibility with the tch library's tensor operations by explicitly setting the tensor kind to float. Moreover, learning rates for the actor and critic have been tuned to achieve more stable training, and deprecated methods from the ndarray library, like .into_shape, are replaced with .into_shape_with_order. Finally, the improved plotting functionality visualizes the performance over episodes.

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, arr1};

use plotters::prelude::*;

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor, Kind};

use tch::nn::{ModuleT};

struct NeuralCritic {

vs: nn::VarStore,

net: nn::Sequential,

}

impl NeuralCritic {

fn new(state_dim: usize, hidden_dim: usize) -> Self {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(tch::Device::Cpu);

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(

&vs.root(),

state_dim as i64,

hidden_dim as i64,

Default::default(),

))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu()) // Add ReLU activation

.add(nn::linear(

&vs.root(),

hidden_dim as i64,

1,

Default::default(),

));

Self { vs, net }

}

fn predict(&self, state: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

// Convert ndarray to tensor with explicit float type

let input = Tensor::of_slice(state.as_slice().unwrap())

.to_kind(Kind::Float) // Ensure float type

.unsqueeze(0);

let output = self.net.forward_t(&input, false); // Use forward_t with train=false for inference

output.squeeze().double_value(&[]) // Convert to f64

}

fn update(&mut self, state: &Array1<f64>, td_error: f64, alpha: f64) {

// Convert ndarray to tensor with explicit float type

let input = Tensor::of_slice(state.as_slice().unwrap())

.to_kind(Kind::Float) // Ensure float type

.unsqueeze(0);

let target = Tensor::of_slice(&[td_error])

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.unsqueeze(0);

let prediction = self.net.forward_t(&input, true); // Use forward_t with train=true for training

// Define loss

let loss = prediction.rsub(&target).pow_tensor_scalar(2.0).mean(None); // Use None for default reduction

// Backpropagation

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&self.vs, alpha).unwrap();

opt.backward_step(&loss);

}

}

struct RobotArmEnv;

impl RobotArmEnv {

fn step(&self, state: &Array1<f64>, _action: usize) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let next_state = state.mapv(|x| x + (rng.gen::<f64>() - 0.5) * 0.1);

let reward = if next_state[0].abs() < 2.0 { 1.0 } else { -1.0 };

let done = reward == -1.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

arr1(&[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]) // Reset to initial state

}

}

fn softmax(policy: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let exp_policy = policy.mapv(f64::exp);

&exp_policy / exp_policy.sum()

}

fn actor_critic(

env: &RobotArmEnv,

episodes: usize,

alpha_actor: f64,

alpha_critic: f64,

gamma: f64,

) -> (Array2<f64>, Vec<f64>) {

let mut actor_params = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 2)); // Actor parameters (state features x actions)

let mut critic = NeuralCritic::new(4, 16); // Neural critic with 16 hidden units

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut cumulative_rewards = Vec::new();

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut episode_reward = 0.0;

loop {

// Compute policy probabilities using softmax

let logits = actor_params.t().dot(&state);

let probabilities = softmax(&logits);

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < probabilities[0] { 0 } else { 1 };

// Take a step in the environment

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(&state, action);

episode_reward += reward;

// TD Error

let v_current = critic.predict(&state);

let v_next = if done { 0.0 } else { critic.predict(&next_state) };

let td_error = reward + gamma * v_next - v_current;

// Update critic

critic.update(&state, td_error, alpha_critic);

// Update actor

let grad = arr1(&[

if action == 0 { probabilities[0] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[0] },

if action == 1 { probabilities[1] - 1.0 } else { probabilities[1] }

]);

// Compute gradient outer product

let grad_outer = grad

.into_shape_with_order((2, 1))

.unwrap()

.dot(&state.clone().into_shape_with_order((1, 4)).unwrap())

.t()

.to_owned();

// Update actor parameters

actor_params.zip_mut_with(&grad_outer, |param, &grad| {

*param += grad * alpha_actor * td_error;

});

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

cumulative_rewards.push(episode_reward);

if episode % 50 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {}", episode, episode_reward);

}

}

(actor_params, cumulative_rewards)

}

fn plot_rewards(rewards: Vec<f64>, episodes: usize) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new("improved_critic_architectures.png", (800, 600))

.into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let max_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Improved Rewards Over Episodes", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(20)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(50)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..episodes, 0.0..max_reward)

.unwrap();

chart

.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("Episodes")

.y_desc("Total Reward")

.draw()

.unwrap();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&BLUE,

))

.unwrap()

.label("Total Rewards")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new([(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &BLUE));

chart

.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE)

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()

.unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let env = RobotArmEnv;

let episodes = 500;

let alpha_actor = 0.001; // Adjusted learning rate

let alpha_critic = 0.01; // Adjusted learning rate

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Training Actor-Critic with Neural Critic...");

let (_, rewards_neural_critic) = actor_critic(&env, episodes, alpha_actor, alpha_critic, gamma);

println!("Plotting results...");

plot_rewards(rewards_neural_critic, episodes);

println!("Plot saved as 'improved_critic_architectures.png'.");

}

The code implements an actor-critic algorithm for reinforcement learning in a simulated robotic arm environment. The actor updates its policy parameters based on the temporal difference (TD) error, which measures the discrepancy between predicted and actual rewards. The critic uses a neural network to approximate the value function, predicting the expected future reward for a given state. During each episode, the agent generates an episode trajectory by selecting actions based on the softmax probabilities of the actor's policy. The critic's predictions are used to compute the TD error, which is then used to update both the critic's neural network weights and the actor's policy parameters. Rewards from each episode are accumulated and visualized using the plotters library, enabling performance analysis.

By replacing the hash map critic with a neural network, the actor-critic model becomes capable of approximating the value function more effectively, especially in continuous or high-dimensional state spaces. The visualization of total rewards over episodes demonstrates the learning progress. The model shows occasional spikes and variability in total rewards, indicating that the learning process is adapting dynamically to the environment's stochastic nature. With properly tuned learning rates (alpha_actor and alpha_critic), the rewards gradually stabilize, showcasing the improved convergence properties of using a neural critic. This highlights the trade-off between the flexibility of a neural critic and the computational simplicity of a hash map-based approach.

This section provides a comprehensive introduction to actor-critic methods, blending theoretical insights with practical Rust implementations. By understanding the interplay between the actor and critic, readers gain the tools to apply these methods to complex reinforcement learning tasks.

9.4. Advanced Policy Gradient Methods: PPO and TRPO

The development of Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) arose from the need to address key challenges in policy gradient methods, particularly the instability and inefficiency of policy updates. Early policy gradient algorithms, such as REINFORCE, while simple and foundational, suffered from high variance in gradient estimates and a lack of constraints on policy updates. These issues often resulted in large, destabilizing changes to policies during training, leading to suboptimal or divergent behavior in complex reinforcement learning environments.

The introduction of Actor-Critic methods marked a significant step forward by combining value-based and policy-based approaches to reduce variance. However, as policy gradient methods gained prominence, particularly in tasks involving high-dimensional or continuous action spaces, the need for more stable and efficient optimization techniques became evident. Large, unconstrained updates in traditional Actor-Critic frameworks could cause the learning process to oscillate or even fail, especially in tasks requiring delicate balance, such as robotics and simulated physics environments. This motivated the exploration of techniques that could stabilize policy updates while preserving the flexibility of policy gradient methods.

Figure 6: The historical evolution of stable policy optimization in RL.

Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO), introduced by Schulman et al. in 2015, was a breakthrough in this regard. TRPO formalized the concept of a trust region, a constraint that ensures new policies remain close to previous policies during optimization. By framing the update as a constrained optimization problem, TRPO prevented drastic policy changes, significantly improving stability and convergence in training. However, while TRPO offered robust performance, its reliance on solving a computationally intensive constrained optimization problem made it challenging to scale to larger and more complex environments.

To address the computational inefficiency of TRPO, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) was introduced by Schulman et al. in 2017. PPO simplified the trust region idea by replacing the hard constraints of TRPO with a clipped surrogate objective, which penalizes updates that move too far from the current policy. This innovation retained most of TRPO’s stability benefits while significantly reducing computational complexity, making PPO more practical and accessible for a wider range of applications. PPO quickly became one of the most popular reinforcement learning algorithms, striking an effective balance between performance, stability, and ease of implementation.

The impact of PPO and TRPO extends beyond traditional reinforcement learning domains like robotics and game-playing. As reinforcement learning began to be integrated with deep learning architectures, these methods proved invaluable for training large-scale models. In particular, PPO became a key algorithm for training agents in simulated environments and complex systems with high-dimensional state and action spaces.

The adoption of PPO in large language models (LLMs) further highlights its versatility and scalability. PPO has been employed in fine-tuning LLMs through techniques like Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), where models are optimized to align with human preferences or specific task objectives. By leveraging PPO’s stability and efficiency, researchers have been able to fine-tune massive language models like OpenAI’s GPT series, ensuring smooth optimization and reliable convergence in training. This adoption underscores the pivotal role of PPO and TRPO in advancing reinforcement learning and their enduring relevance in both classical and cutting-edge applications.

Figure 7: TRPO vs PPO algorithm.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) are two advanced policy gradient methods that address the instability and inefficiency of standard policy gradient algorithms. Both methods focus on ensuring stable policy updates, a critical requirement in reinforcement learning, particularly in environments with high-dimensional or continuous action spaces.

TRPO introduces the concept of a trust region, which constrains policy updates to prevent drastic changes that might destabilize learning. By formulating the optimization as a constrained problem, TRPO ensures that the new policy remains close to the previous one while improving performance. PPO simplifies this idea by using a clipped surrogate objective, which avoids the need for the computationally expensive constraints of TRPO while retaining most of its benefits. These approaches are widely regarded as state-of-the-art methods for training agents in complex environments, offering a balance between performance and stability.

TRPO defines a trust region as a neighborhood around the current policy where updates are considered safe. This is achieved by maximizing the policy objective while constraining the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the old and new policies:

$$ \max_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \frac{\pi_\theta(a|s)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(a|s)} A(s, a) \right], $$

subject to: $\mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ D_{\text{KL}} \left( \pi_\theta(\cdot|s) \| \pi_{\text{old}}(\cdot|s) \right) \right] \leq \delta,$ where $\delta$ is a predefined threshold, and $A(s, a)$ is the advantage function.

The KL divergence quantifies the difference between the old and new policies. By constraining this divergence, TRPO ensures that the new policy does not deviate too far, reducing the risk of destabilizing updates. However, solving this constrained optimization problem requires second-order optimization techniques, making TRPO computationally expensive.

PPO simplifies TRPO by introducing a clipped surrogate objective that approximates the trust region:

$$ L^\text{CLIP}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\text{old}}} \left[ \min \left( r(\theta) A(s, a), \text{clip}(r(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon) A(s, a) \right) \right], $$

where: $r(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a|s)}{\pi_{\text{old}}(a|s)}.$

The clip function prevents $r(\theta)$ from deviating too far from 1, ensuring that updates remain stable. The parameter $\epsilon$ controls the extent of clipping. Unlike TRPO, PPO does not require second-order optimization, making it more computationally efficient while retaining much of the stability benefits.

Both PPO and TRPO address a critical issue in reinforcement learning: the instability of standard policy gradient methods. Large updates to the policy can lead to performance degradation, particularly in environments with sparse rewards or complex dynamics. By constraining or clipping updates, these methods ensure that the learning process remains stable and efficient, enabling agents to converge to optimal policies more reliably.

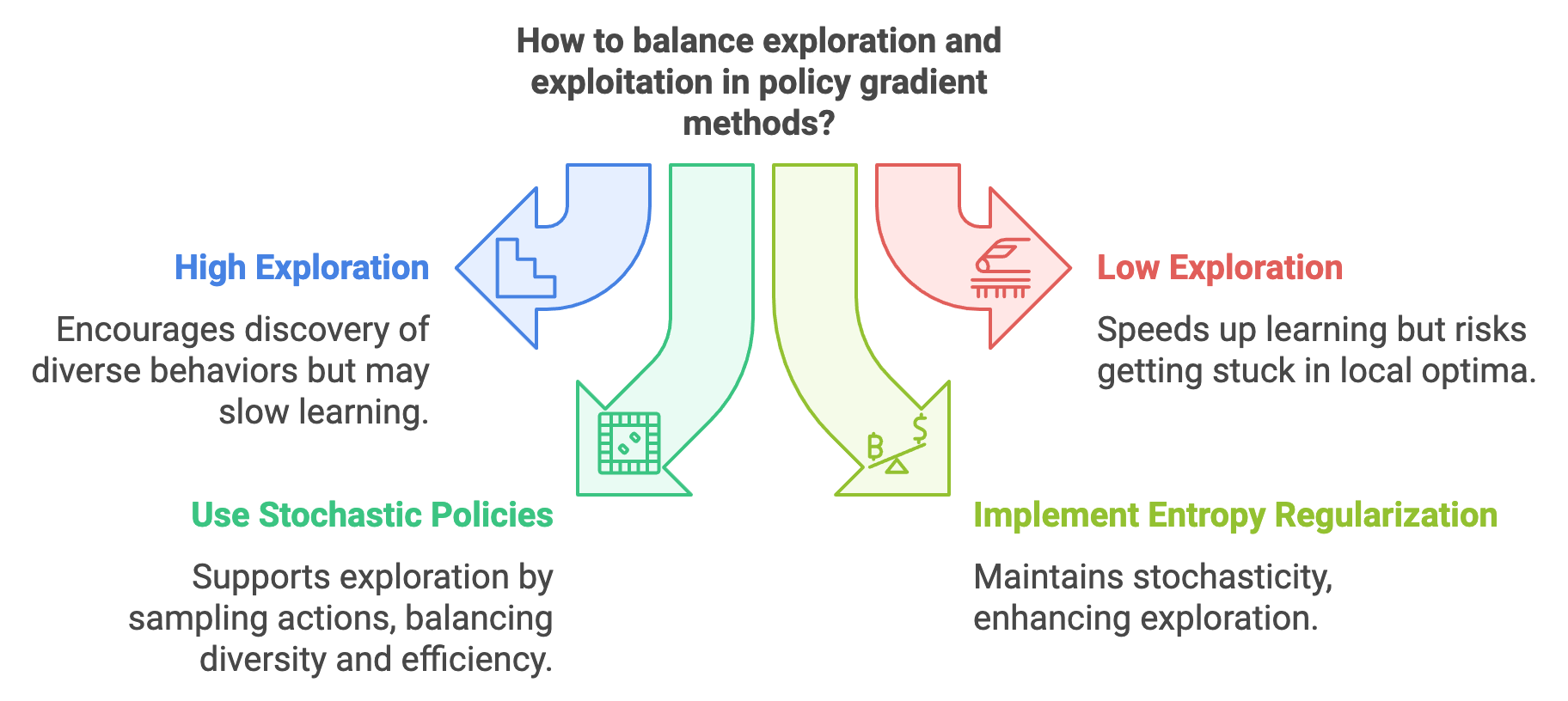

Entropy regularization is a technique used in PPO to encourage exploration by preventing the policy from becoming overly deterministic. The entropy of a policy $\pi_\theta$ is given by:

$$ H(\pi_\theta) = -\sum_a \pi_\theta(a|s) \log \pi_\theta(a|s). $$

Adding an entropy term to the PPO objective incentivizes the agent to maintain randomness in action selection, which is particularly useful in environments with uncertain dynamics or multiple optimal solutions. This regularization balances exploitation and exploration, enabling the agent to discover better policies over time.

PPO and TRPO share the goal of stabilizing policy updates, but they differ in complexity and computational requirements. TRPO’s constrained optimization ensures precise control over policy updates but requires second-order optimization, making it resource-intensive. PPO, by contrast, uses a simpler clipped objective, offering a balance between stability and computational efficiency. This simplicity has made PPO a popular choice in many applications, particularly when computational resources are limited.

This code implements a reinforcement learning approach using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm in a simulated environment. The SimulatedEnv represents a toy environment where the agent transitions between states by taking actions influenced by Gaussian noise. The goal is to optimize the policy parameters such that the agent minimizes the absolute sum of state values while avoiding exceeding a defined boundary condition.

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use rand::thread_rng;

use rand_distr::{Distribution, Normal};

struct SimulatedEnv;

impl SimulatedEnv {

fn step(&self, state: &Array1<f64>, action: &Array1<f64>) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let noise_dist = Normal::new(0.0, 0.1).unwrap();

let next_state = state + &action.mapv(|x| x + noise_dist.sample(&mut rng));

let reward = -next_state.mapv(|x| x.abs()).sum();

let done = next_state.mapv(|x| x.abs()).sum() > 10.0;

(next_state, reward, done)

}

fn reset(&self) -> Array1<f64> {

Array1::zeros(4)

}

}

fn compute_policy_action(state: &Array1<f64>, policy_params: &Array2<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let noise_dist = Normal::new(0.0, 0.1).unwrap();

let logits = policy_params.dot(state);

logits.mapv(|x| x + noise_dist.sample(&mut rng))

}

fn ppo(env: &SimulatedEnv, episodes: usize, learning_rate: f64, gamma: f64, epsilon: f64) -> Array2<f64> {

let mut policy_params = Array2::<f64>::zeros((4, 4));

let mut value_params = Array1::<f64>::zeros(4);

for _ in 0..episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut trajectories = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..100 {

let action = compute_policy_action(&state, &policy_params);

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(&state, &action);

trajectories.push((state.clone(), action.clone(), reward, next_state.clone()));

if done {

break;

}

state = next_state;

}

for (state, _action, reward, next_state) in &trajectories {

// Value function update

let current_value = value_params.dot(state);

let next_value = value_params.dot(next_state);

let td_error = (reward + gamma * next_value - current_value).clamp(-1.0, 1.0);

value_params += &(learning_rate * td_error * state);

// Policy update

let policy_logits = policy_params.dot(state);

let max_logit = policy_logits.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let stable_logits = policy_logits.mapv(|x| x - max_logit);

let ratio = stable_logits.mapv(|x| x.exp()) / stable_logits.mapv(|x| x.exp()).sum();

let clipped_ratio = ratio.mapv(|r| r.clamp(1.0 - epsilon, 1.0 + epsilon));

for i in 0..policy_params.nrows() {

for j in 0..policy_params.ncols() {

policy_params[[i, j]] += learning_rate * clipped_ratio[i] * td_error * state[j];

}

}

}

}

policy_params

}

fn main() {

let env = SimulatedEnv;

let episodes = 500;

let learning_rate = 0.01;

let gamma = 0.99;

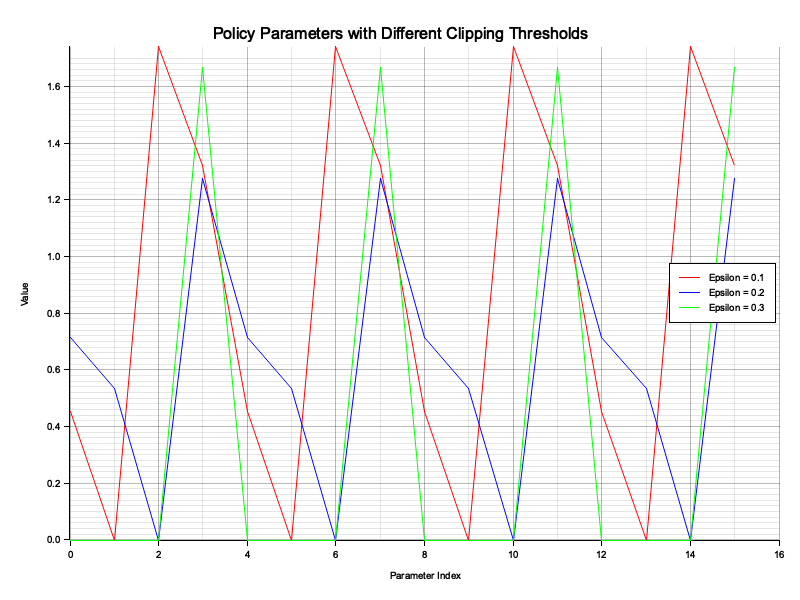

for epsilon in [0.1, 0.2, 0.3] {

println!("Training PPO with epsilon = {}...", epsilon);

let policy_params = ppo(&env, episodes, learning_rate, gamma, epsilon);

println!("Learned Policy Parameters:\n{}", policy_params);

}

}

The code trains a policy using the PPO algorithm over multiple episodes. Each episode collects a trajectory of state-action-reward transitions by interacting with the environment using the current policy. The value function is updated using temporal difference (TD) error, which measures the discrepancy between the predicted and observed returns. The policy is updated by maximizing a clipped surrogate objective function to ensure stability in learning. For each training run, the algorithm iterates over a range of epsilon values, which control the extent of clipping in the policy update. At the end of training, the learned policy parameters for each epsilon value are displayed.

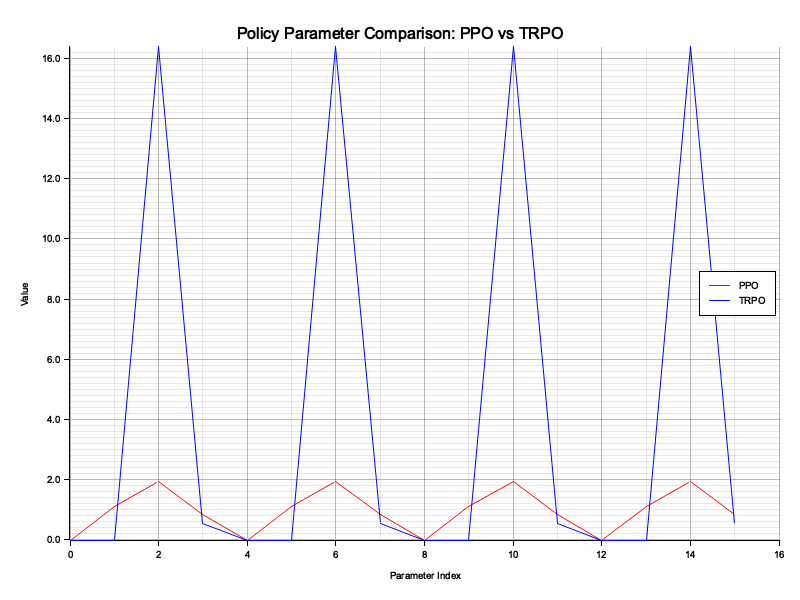

This code implements and compares two reinforcement learning algorithms: Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO). Both methods aim to optimize policy parameters for a simulated environment where the agent minimizes the sum of absolute state values. While PPO uses a clipped surrogate objective to stabilize policy updates, TRPO imposes a trust region constraint to limit the divergence between consecutive policies. The goal of this experiment is to evaluate the performance and stability of the two algorithms by comparing their learned policy parameters after training.

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use rand::thread_rng;

use rand_distr::{Distribution, Normal};

use plotters::prelude::*;

struct SimulatedEnv;

impl SimulatedEnv {

fn step(&self, state: &Array1<f64>, action: &Array1<f64>) -> (Array1<f64>, f64, bool) {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let noise_dist = Normal::new(0.0, 0.1).unwrap();

let next_state = state + &action.mapv(|x| x + noise_dist.sample(&mut rng));

let reward = -next_state.mapv(|x| x.abs()).sum();

let done = next_state.mapv(|x| x.abs()).sum() > 10.0;