Chapter 13

Learning in Multi-Agent Systems

"Learning is the only thing the mind never exhausts, never fears, and never regrets." — Leonardo da Vinci

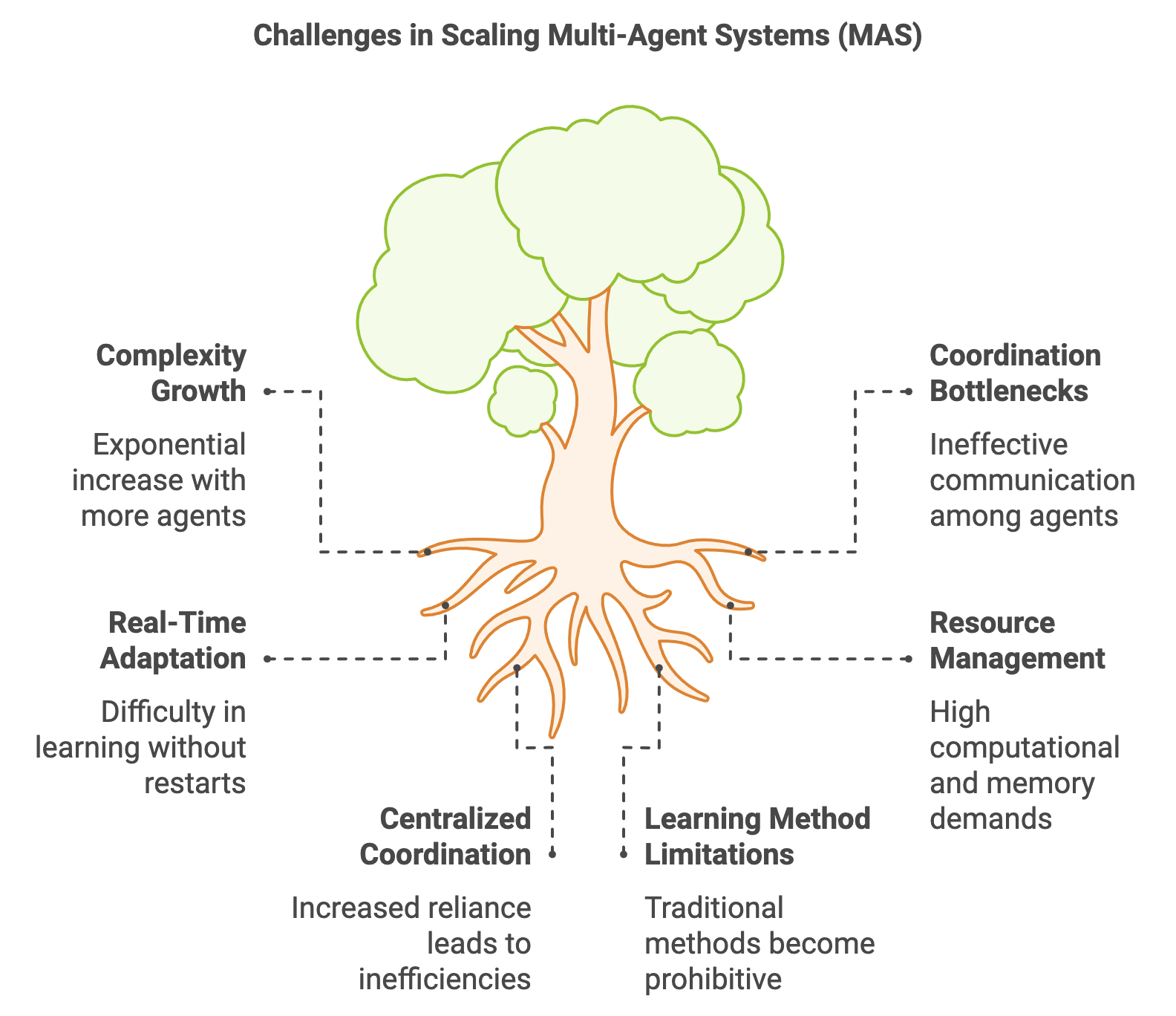

Chapter 13 focuses on the core principles, advanced techniques, and practical implementations of learning in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS). It begins by establishing a mathematical foundation for decentralized, centralized, and hybrid learning paradigms, emphasizing challenges such as non-stationarity, credit assignment, and scalability. The chapter explores independent learning, centralized policy optimization, and adaptive learning, highlighting their theoretical strengths and practical applications in cooperative, competitive, and hybrid environments. Techniques like reward decomposition, opponent modeling, and hierarchical learning are discussed in depth to address real-world complexities. Practical Rust-based implementations allow readers to experiment with scalable, efficient, and ethical learning systems, making Chapter 13 a comprehensive guide to mastering MAS learning.

13.1. Fundamentals of Learning in MAS

Learning in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) represents a frontier in artificial intelligence, where autonomous agents interact within a shared environment to optimize their strategies and achieve individual or collective goals. Unlike single-agent systems, MAS introduces a unique set of complexities, stemming from the dynamics of cooperation, competition, and partial observability, as well as the inherent non-stationarity caused by the simultaneous learning of multiple agents. These factors necessitate sophisticated frameworks and algorithms that enable agents to adapt, collaborate, and compete effectively in dynamic, high-dimensional settings. This section explores the theoretical principles, conceptual paradigms, and practical implementations that underpin learning in MAS, with a focus on leveraging Rust for scalable and robust applications.

The learning process in MAS is fundamentally shaped by the nature of interactions among agents. Cooperative scenarios require agents to align their strategies to achieve shared objectives, such as maximizing resource utilization in a smart grid or coordinating movements in a drone swarm. Competition, on the other hand, involves agents vying for limited resources or opposing goals, as seen in financial markets or adversarial games. Mixed environments combine elements of both, where agents must balance collaboration with self-interest, such as in autonomous vehicle systems navigating shared roadways. These varying dynamics introduce challenges in designing learning algorithms that can adapt to diverse interaction patterns while ensuring fairness, efficiency, and scalability.

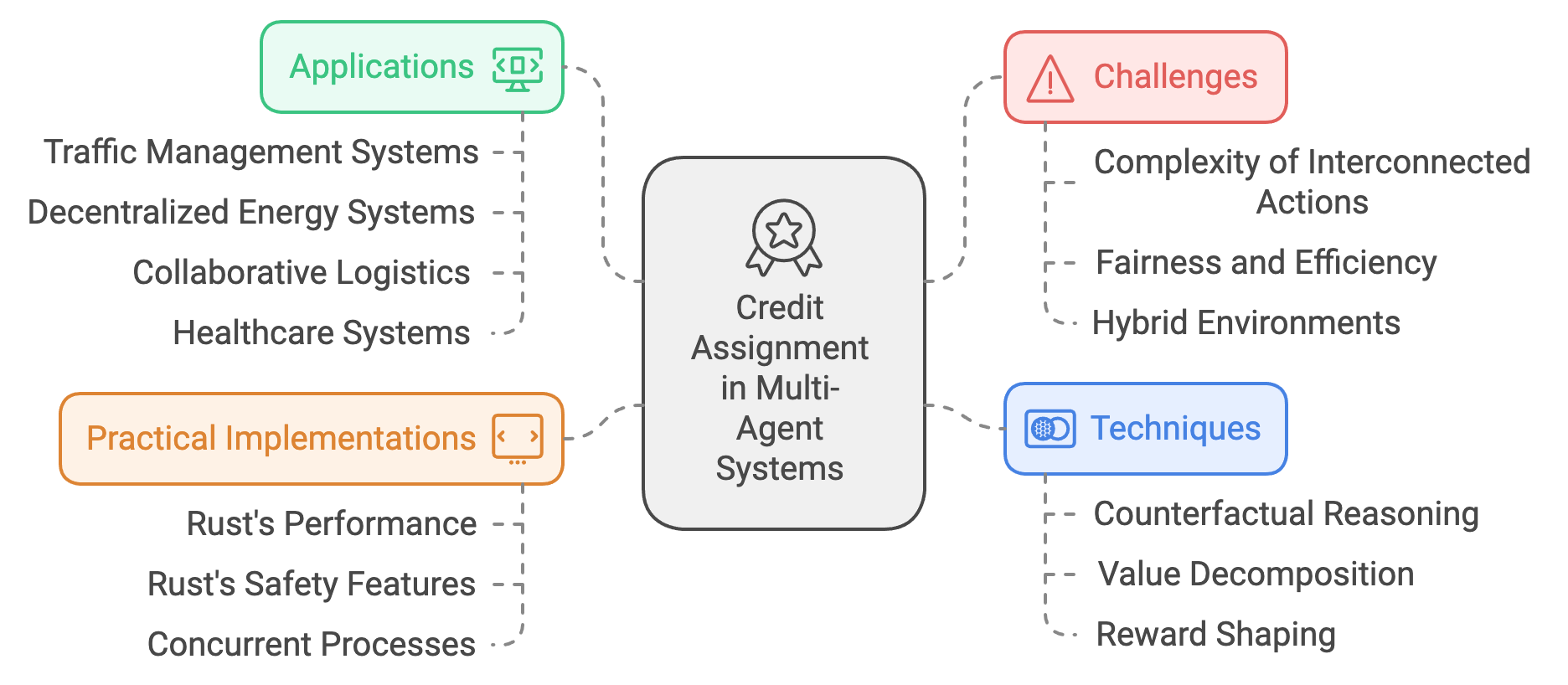

Figure 1: The Dynamics of MAS Implementations.

One of the defining complexities of MAS is non-stationarity, where the environment evolves as agents continuously update their strategies. In single-agent systems, the environment is typically static or changes predictably, but in MAS, the actions of one agent influence the learning process of others, creating a feedback loop that complicates strategy optimization. For instance, in competitive settings like cybersecurity, the strategies of attackers and defenders evolve in response to each other, requiring agents to anticipate and adapt to shifting threats and defenses. This dynamic interplay demands algorithms capable of modeling and predicting the behaviors of other agents, such as opponent modeling or policy prediction frameworks.

Partial observability further complicates learning in MAS. Agents often operate with incomplete or noisy information about the environment and the actions of other agents, making it difficult to form accurate predictions or optimize strategies. For example, in decentralized energy systems, individual households may lack visibility into the consumption patterns of others, yet they must adapt their energy usage to balance demand and supply. Addressing partial observability requires the integration of advanced learning paradigms, such as decentralized training with shared objectives or the use of communication protocols to enhance information sharing among agents.

Conceptual paradigms for learning in MAS span a spectrum of approaches, including value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic methods. Value-based methods, such as Q-learning, enable agents to estimate the long-term benefits of actions and optimize their strategies accordingly. These methods are particularly effective in cooperative environments where shared rewards guide collective behavior. Policy-based methods directly optimize the agent’s decision-making process, making them well-suited for continuous action spaces, as seen in autonomous vehicle navigation or robotic control. Actor-critic methods combine the strengths of both, leveraging value functions to stabilize policy optimization in complex, high-dimensional tasks. These paradigms provide the foundation for a wide range of MARL algorithms, including centralized and decentralized training approaches.

Centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) has emerged as a prominent paradigm for learning in MAS. In this framework, agents are trained collectively using shared information during the learning phase, enabling them to develop strategies that consider the global context. Once trained, they execute their policies independently, relying only on local observations. CTDE is particularly valuable in scenarios like swarm robotics, where centralized training ensures coordination, but real-time execution requires decentralized decision-making due to communication constraints. This approach balances the benefits of collaboration during training with the scalability of decentralized operations.

In competitive environments, advanced techniques like multi-agent counterfactual reasoning and adversarial learning enable agents to optimize strategies in the presence of adversaries. Counterfactual reasoning allows agents to evaluate the impact of their actions on shared outcomes, fostering fairness and improving credit assignment in cooperative tasks. Adversarial learning, by contrast, equips agents to anticipate and counteract the strategies of opponents, enhancing robustness in security and game-theoretic applications.

Practical implementations of learning in MAS benefit significantly from Rust’s performance, concurrency, and safety features. Rust’s ability to handle parallel computations and manage resources efficiently makes it ideal for simulating large-scale MAS environments. For example, in smart transportation systems, Rust can simulate thousands of autonomous vehicles interacting in real time, ensuring that learning algorithms scale to the demands of urban traffic management. Similarly, in decentralized financial systems, Rust’s robust concurrency model enables the simulation of high-frequency trading agents optimizing their strategies in competitive markets.

In addition to its technical advantages, Rust’s growing ecosystem of libraries supports the development of MARL applications. Libraries like tch for deep learning, async-std for concurrency, and tokio for networking provide the tools needed to build scalable, high-performance MAS simulations. For instance, a Rust-based implementation of a multi-agent drone swarm could leverage tch to train neural networks for navigation, while using tokio to manage real-time communication among agents. These capabilities allow developers to translate theoretical insights into practical, impactful systems that address real-world challenges.

Learning in MAS represents a confluence of theoretical innovation, algorithmic sophistication, and practical engineering. By integrating advanced learning paradigms with robust implementation frameworks like Rust, MAS can address complex, dynamic problems in domains ranging from autonomous systems and cybersecurity to energy management and decentralized finance. This exploration highlights the transformative potential of MAS, offering a roadmap for researchers and practitioners to harness the power of multi-agent learning in creating intelligent, scalable, and adaptive systems.

The dynamics of MAS can be modeled using Markov Games or Decentralized Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (Dec-POMDPs). A Markov Game is defined as a tuple:

$$ G = (\mathcal{S}, \{\mathcal{A}_i\}_{i=1}^n, P, \{u_i\}_{i=1}^n, \gamma), $$

where $\mathcal{S}$ is the state space, $\mathcal{A}_i$ is the action set of agent $i$, $P: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \to \Delta(\mathcal{S})$ is the transition function, and $u_i: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \to \mathbb{R}$ is the reward function for agent $i$. The joint action space $\mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_1 \times \mathcal{A}_2 \times \cdots \times \mathcal{A}_n$ captures the combined actions of all agents. The agents aim to maximize their cumulative discounted rewards:

$$ R_i = \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t u_i(s_t, a_t)\right], $$

where $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor, and $s_t$ and $a_t$ represent the state and joint action at time $t$, respectively.

In scenarios with incomplete information, Dec-POMDPs generalize Markov Games by associating each agent $i$ with an observation $o_i$ derived from the underlying state $s$. The policy $\pi_i(o_i)$ is optimized to maximize expected rewards based on partial observations. The Dec-POMDP framework is mathematically defined as:

$$ \pi_i^* = \arg\max_{\pi_i} \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t u_i(s_t, a_t) \mid o_i\right]. $$

Policy optimization in MAS can be decentralized, centralized, or hybrid. Decentralized methods involve independent agents optimizing individual policies, while centralized approaches optimize a joint policy over the entire system. Hybrid methods, such as Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE), balance these approaches by using centralized information during training to guide decentralized execution.

Independent learning treats other agents as part of the environment. Each agent optimizes its policy without explicit coordination, leading to potential instability due to environment non-stationarity. Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) mitigates this issue by sharing global information during training, enabling agents to learn complementary policies. This paradigm is especially effective in cooperative tasks, where alignment of objectives is critical.

Environment non-stationarity is a central challenge in MAS learning. As agents adapt their policies, the effective dynamics of the environment change, violating the Markov property. Stabilizing techniques such as experience replay, opponent modeling, and policy regularization are often employed to address this.

Synchronous and asynchronous learning methods govern the temporal coordination of agent updates. Synchronous methods ensure that all agents update simultaneously, which simplifies coordination but requires global synchronization. Asynchronous methods allow agents to update at different intervals, improving scalability but introducing complexities in maintaining system-wide stability.

The provided Rust implementation simulates a Multi-Agent System (MAS) using Markov Game dynamics. This model consists of an environment (MultiAgentEnv) and multiple agents (Agent) interacting in a stateful environment. The environment defines a state space, an action space, transition dynamics, and rewards for agents based on their joint actions. Agents adapt their policies over time by learning from rewards, employing a simple reward-driven policy update mechanism.

use ndarray::{Array1, Array3, s};

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

/// Represents a Multi-Agent Environment with Markov Game dynamics.

struct MultiAgentEnv {

num_agents: usize,

state_space: usize,

action_space: usize,

transition_matrix: Array3<f64>, // Transition probabilities for joint actions

reward_matrix: Array3<f64>, // Rewards for joint actions

}

impl MultiAgentEnv {

fn new(

num_agents: usize,

state_space: usize,

action_space: usize,

transition_matrix: Array3<f64>,

reward_matrix: Array3<f64>,

) -> Self {

assert_eq!(transition_matrix.shape(), &[state_space, action_space, action_space]);

assert_eq!(reward_matrix.shape(), &[state_space, num_agents, action_space]);

Self {

num_agents,

state_space,

action_space,

transition_matrix,

reward_matrix,

}

}

/// Simulates the environment for a given state and joint actions.

fn step(&self, state: usize, actions: &[usize]) -> (usize, Vec<f64>) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Determine next state based on transition probabilities

let joint_action = actions[0]; // Simplified for pairwise actions

let probs = self.transition_matrix.slice(s![state, joint_action, ..]);

let cumulative: Vec<f64> = probs

.iter()

.scan(0.0, |acc, &p| {

*acc += p;

Some(*acc)

})

.collect();

let r = rng.gen::<f64>();

let next_state = cumulative.iter().position(|&c| r < c).unwrap_or(state);

// Calculate rewards for all agents

let rewards: Vec<f64> = (0..self.num_agents)

.map(|i| self.reward_matrix[[state, i, joint_action]])

.collect();

(next_state, rewards)

}

// Add method to demonstrate use of state_space and action_space

fn get_state_action_info(&self) -> (usize, usize) {

(self.state_space, self.action_space)

}

}

/// Represents an agent learning in the MAS.

struct Agent {

action_space: usize,

policy: Array1<f64>,

learning_rate: f64,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(action_space: usize, learning_rate: f64) -> Self {

let initial_policy = Array1::from_elem(action_space, 1.0 / action_space as f64);

Self {

action_space,

policy: initial_policy,

learning_rate,

}

}

/// Updates the agent's policy using a reward-driven learning rule.

fn update_policy(&mut self, action: usize, reward: f64) {

self.policy[action] += self.learning_rate * reward;

let sum: f64 = self.policy.iter().sum();

self.policy /= sum; // Normalize the policy

}

// Add method to demonstrate use of action_space

fn get_action_space(&self) -> usize {

self.action_space

}

}

/// Visualizes the evolution of agent policies.

fn visualize_policy_evolution(

policy_history: &[Vec<Array1<f64>>],

filename: &str,

) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (800, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let max_time = policy_history.len();

let num_agents = policy_history[0].len();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Policy Evolution", ("sans-serif", 20))

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..max_time, 0.0..1.0)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

for agent in 0..num_agents {

for action in 0..policy_history[0][agent].len() {

let series = policy_history.iter().enumerate().map(|(t, policies)| {

(t, policies[agent][action])

});

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(series, &Palette99::pick(agent * 3 + action)))

.unwrap()

.label(format!("Agent {} Action {}", agent + 1, action + 1));

}

}

chart.configure_series_labels().draw()?;

Ok(())

}

/// Simulates MAS learning in static and dynamic environments.

fn simulate_mas_learning() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let num_agents = 2;

let state_space = 3;

let action_space = 2;

let transition_matrix = Array3::from_shape_vec(

(state_space, action_space, action_space),

vec![

0.8, 0.2, 0.2, 0.8, // State 0

0.7, 0.3, 0.3, 0.7, // State 1

0.6, 0.4, 0.4, 0.6, // State 2

],

)

.unwrap();

let reward_matrix = Array3::from_shape_vec(

(state_space, num_agents, action_space),

vec![

1.0, 0.0, 0.5, 0.5, // State 0

0.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.5, // State 1

0.5, 0.5, 1.0, 0.0, // State 2

],

)

.unwrap();

let env = MultiAgentEnv::new(num_agents, state_space, action_space, transition_matrix, reward_matrix);

// Demonstrate use of get_state_action_info

let (states, actions) = env.get_state_action_info();

println!("Environment has {} states and {} actions", states, actions);

let mut agents: Vec<Agent> = vec![

Agent::new(action_space, 0.1),

Agent::new(action_space, 0.1),

];

// Demonstrate use of get_action_space

for (i, agent) in agents.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Agent {} action space: {}", i, agent.get_action_space());

}

let mut state = 0;

let mut policy_history: Vec<Vec<Array1<f64>>> = vec![];

for _ in 0..50 {

let actions: Vec<usize> = agents

.iter()

.map(|agent| {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let probs: Vec<f64> = agent.policy.to_vec();

let cumulative: Vec<f64> = probs

.iter()

.scan(0.0, |acc, &p| {

*acc += p;

Some(*acc)

})

.collect();

let r = rng.gen::<f64>();

cumulative.iter().position(|&c| r < c).unwrap_or(0)

})

.collect();

let (next_state, rewards) = env.step(state, &actions);

for (agent, (&action, &reward)) in agents.iter_mut().zip(actions.iter().zip(rewards.iter())) {

agent.update_policy(action, reward);

}

policy_history.push(agents.iter().map(|agent| agent.policy.clone()).collect());

state = next_state;

}

visualize_policy_evolution(&policy_history, "policy_evolution.png")?;

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

simulate_mas_learning()?;

Ok(())

}

The environment defines state transitions and rewards using transition and reward matrices. In each iteration, agents select actions based on their policies, which are probabilistic distributions over their action spaces. The environment calculates the next state and rewards for the agents based on their joint actions and the current state. Each agent then updates its policy using a learning rule, gradually improving its performance based on observed rewards. The simulation iterates over multiple rounds, tracking the evolution of policies for all agents. The policy history is visualized as a line chart, showing how agents' strategies evolve over time.

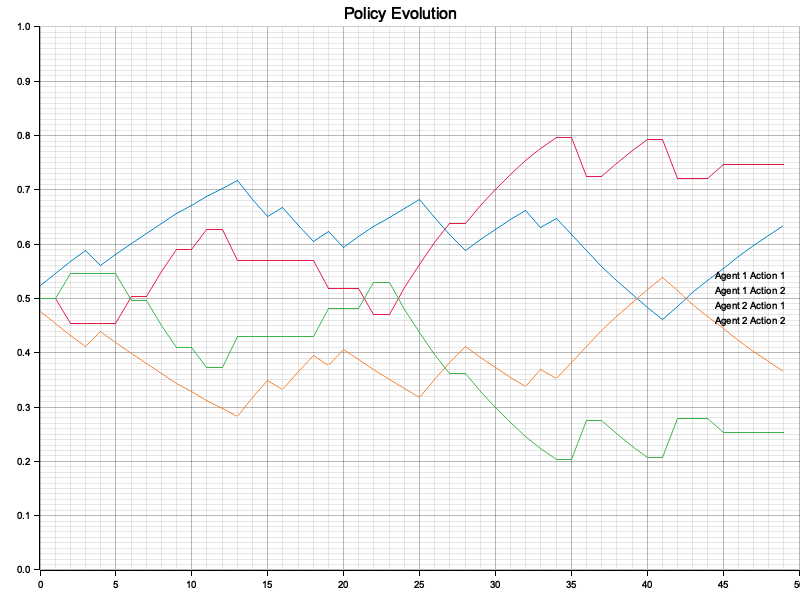

Figure 2: Plotters visualization of the Policy Evolution.

The Policy Evolution chart provides a clear depiction of how agents dynamically adjust their strategies over time in response to environmental feedback. Initially, the probabilities for each action fluctuate significantly as the agents explore different actions and adapt to the rewards received, showcasing their learning process. As the simulation progresses, the agents' policies begin to stabilize, indicating convergence toward optimal strategies suited to the environment's dynamics and reward structures. The chart also reveals the interplay between competition and cooperation among agents, where some actions (e.g., Agent 1 Action 1) emerge as dominant due to higher rewards, while less beneficial actions diminish in probability. This visualization illustrates how agents learn and adapt in a multi-agent system, eventually balancing their strategies to maximize their overall performance, leading to the emergence of equilibrium behavior.

Learning in Multi-Agent Systems integrates theoretical rigor with practical implementation to address the challenges of decentralized decision-making in dynamic environments. By modeling interactions using Markov Games and Dec-POMDPs, exploring learning paradigms like CTDE, and implementing scalable simulations in Rust, this chapter equips practitioners to design robust, high-performance MAS solutions.

13.2. Independent Learning in Multi-Agent Systems

Independent learning in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) represents a decentralized approach where each agent individually learns policies to maximize its own rewards without explicitly coordinating with others. This paradigm aligns well with environments where centralized control is either impractical due to scalability constraints or infeasible due to communication limitations. By enabling agents to operate autonomously, independent learning offers computational scalability and flexibility, making it applicable to a wide range of real-world scenarios. However, the absence of coordination introduces complexities that necessitate careful algorithmic design and strategic implementation.

At its core, independent learning operates on the premise that each agent perceives and interacts with the environment from its own perspective, optimizing its strategy based solely on local observations and feedback. This decentralization reduces computational overhead, as agents do not need to process or share global information. This makes independent learning particularly well-suited for large-scale applications, such as swarm robotics, where individual drones perform localized tasks like mapping or search-and-rescue without relying on centralized commands. Similarly, in decentralized financial systems, independent learning allows agents representing traders or validators to optimize their strategies autonomously, adapting to rapidly changing market conditions.

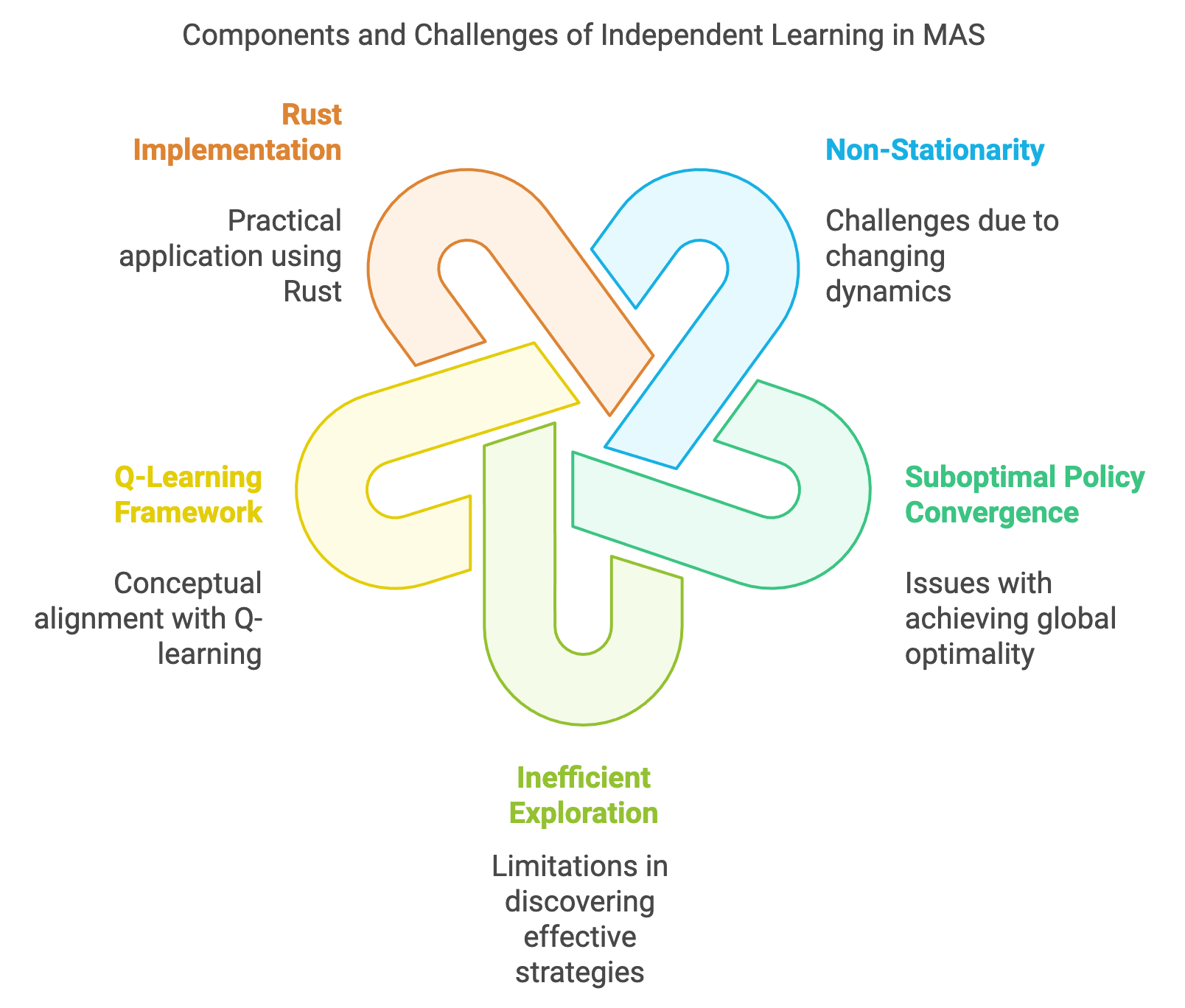

Figure 3: Scopes of Independent Learning in MAS with Rust.

Despite its advantages, independent learning introduces several challenges that stem from the interactions among agents in shared environments. One of the most significant challenges is non-stationarity, where the environment’s dynamics change as other agents simultaneously learn and adapt their strategies. For an individual agent, this means that the reward structures and state transitions it experiences are constantly shifting, making it difficult to converge to stable policies. For example, in autonomous driving, vehicles learning independently may disrupt each other’s learning processes by altering traffic patterns unpredictably, leading to erratic or suboptimal behaviors.

Another critical challenge is suboptimal policy convergence, where independent agents may settle on strategies that maximize individual rewards but fail to achieve globally optimal outcomes. This phenomenon, often referred to as the "tragedy of the commons," occurs when agents prioritize short-term gains over long-term collective benefits. For instance, in shared resource environments like energy grids, independent agents optimizing for personal cost savings may destabilize the grid by failing to consider collective demand patterns. Addressing this issue requires mechanisms that indirectly guide agents toward more cooperative behaviors without imposing explicit coordination.

Inefficient exploration is another limitation of independent learning, as agents exploring the environment in isolation may fail to discover strategies that are effective in multi-agent contexts. In competitive environments, agents may exploit each other's exploration inefficiencies, creating imbalanced or adversarial dynamics. For example, in competitive multiplayer games, an independent learning agent may repeatedly lose to opponents exploiting its predictable exploration patterns, resulting in slower or stagnated learning progress.

Conceptually, independent learning aligns with frameworks like Q-learning, where agents individually estimate the value of actions based on their experiences. However, adapting such frameworks to multi-agent settings requires addressing the non-stationary dynamics introduced by concurrent learners. Techniques such as experience replay, which reuses past interactions for training, can help stabilize learning by providing a consistent training distribution. Additionally, strategies like reward shaping and intrinsic motivation can encourage agents to explore more diverse behaviors, mitigating the risk of getting trapped in local optima.

From a practical standpoint, implementing independent learning in MAS necessitates robust computational frameworks capable of handling parallel learning processes. Rust, with its emphasis on performance, safety, and concurrency, provides an ideal platform for developing scalable and reliable MAS applications. Its asynchronous programming capabilities enable the efficient simulation of independent agents interacting in real time, while its memory safety features ensure robustness in complex, dynamic environments.

For example, a Rust-based implementation of independent learning in a drone swarm might involve agents independently optimizing their navigation strategies based on local sensory inputs. By leveraging Rust’s tokio for asynchronous communication and tch for neural network-based policy learning, such a system can simulate thousands of agents operating simultaneously. The modularity of Rust’s ecosystem also facilitates the integration of advanced features like adaptive exploration or heuristic-based reward shaping, enhancing the efficiency and robustness of independent learning processes.

Independent learning also finds applications in scenarios like warehouse automation, where robots operate autonomously to transport goods without centralized oversight. Each robot learns to optimize its path planning and task allocation based on local conditions, such as shelf proximity or congestion. Similarly, in decentralized water management systems, agents representing different regions independently adjust water usage and distribution strategies to maximize efficiency and sustainability while responding to local supply and demand dynamics.

In conclusion, independent learning in MAS is a powerful approach for enabling decentralized, scalable, and autonomous decision-making. While it introduces challenges such as non-stationarity, suboptimal policy convergence, and exploration inefficiencies, these can be addressed through thoughtful algorithmic enhancements and robust implementation frameworks. Rust’s capabilities make it an excellent choice for developing MAS applications, ensuring the reliability and scalability of independent learning systems. By embracing the opportunities and mitigating the limitations of independent learning, MAS can drive innovation in diverse domains, from autonomous vehicles and robotics to finance and resource management.

In a multi-agent environment, the behavior of each agent $i$ is described by a policy $\pi_i: \mathcal{S} \to \Delta(\mathcal{A}_i)$, which maps states $s \in \mathcal{S}$ to a probability distribution over actions $a_i \in \mathcal{A}_i$. Each agent aims to optimize its policy to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

$$ \max_{\pi_i} \mathbb{E}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_i(s_t, a_{i,t}) \mid \pi_i \right], $$

where $r_i(s_t, a_{i,t})$ is the reward received by agent $i$ at time $t$, $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor, and the expectation is over the joint distribution of states and actions induced by $\pi_i$ and the environment dynamics.

Each agent approximates the value of state-action pairs using a Q-function $Q_i(s, a_i)$, which represents the expected cumulative reward for taking action $a_i$ in state $s$ and following policy $\pi_i$ thereafter. The Q-function is updated iteratively using the Bellman equation:

$$ Q_i(s, a_i) \leftarrow Q_i(s, a_i) + \alpha \left[ r_i + \gamma \max_{a_i'} Q_i(s', a_i') - Q_i(s, a_i) \right], $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, $r_i$ is the immediate reward, $s'$ is the next state, and $\max_{a_i'} Q_i(s', a_i')$ represents the best possible Q-value in the next state.

The policy $\pi_i$ is derived from $Q_i$ using an exploration-exploitation strategy. A common approach is $\epsilon$-greedy, where the agent selects a random action with probability ϵ\\epsilonϵ and the action maximizing $Q_i$ otherwise. Formally, the policy is:

$$ \pi_i(a_i \mid s) = \begin{cases} \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}_i|} + (1 - \epsilon), & \text{if } a_i = \arg\max_{a_i'} Q_i(s, a_i'), \\ \frac{\epsilon}{|\mathcal{A}_i|}, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} $$

Exploration ensures that the agent samples all possible actions sufficiently, while exploitation focuses on actions with higher expected rewards.

In multi-agent settings, the environment perceived by each agent changes dynamically as other agents adapt their policies. This non-stationarity violates the Markov property, making the convergence of independent Q-learning uncertain. Each agent optimizes its Q-function assuming a stationary environment, but the policies of other agents create a moving target, leading to oscillations or suboptimal policies.

Another fundamental challenge is the credit assignment problem, particularly in cooperative or mixed environments. An agent may receive rewards influenced by the actions of others, making it difficult to disentangle the contribution of its own actions. This ambiguity can result in inefficient learning or failure to converge to optimal joint strategies.

Despite these challenges, independent learning is computationally efficient and well-suited for large-scale systems where the cost of coordination outweighs the benefits. It is commonly applied in resource allocation, swarm robotics, and decentralized traffic management.

The code implements a Multi-Agent System (MAS) in a shared grid world environment where two agents use independent Q-learning to maximize their individual rewards. The agents navigate a grid with defined reward locations and independently update their policies through interactions with the environment. The framework incorporates reinforcement learning concepts such as epsilon-greedy exploration, Q-value updates, and exploration decay, allowing the agents to balance exploration and exploitation over time. Additionally, a visualization of the learned Q-tables as heatmaps provides insights into the policies the agents develop during training.

use ndarray::Array2;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

/// A grid-based environment where agents navigate to maximize rewards.

struct GridEnvironment {

grid_size: usize,

rewards: Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>, // Positions and corresponding rewards

}

impl GridEnvironment {

fn new(grid_size: usize, rewards: Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>) -> Self {

Self { grid_size, rewards }

}

/// Returns the reward for a specific position.

fn get_reward(&self, x: usize, y: usize) -> f64 {

self.rewards

.iter()

.find(|&&(rx, ry, _)| rx == x && ry == y)

.map(|&(_, _, reward)| reward)

.unwrap_or(0.0)

}

}

/// An independent learning agent implementing Q-learning.

struct Agent {

q_table: Array2<f64>, // Q-values for all state-action pairs

position: (usize, usize),

grid_size: usize,

epsilon: f64,

alpha: f64,

gamma: f64,

decay_rate: f64,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(grid_size: usize, epsilon: f64, alpha: f64, gamma: f64, decay_rate: f64) -> Self {

let q_table = Array2::zeros((grid_size * grid_size, 4)); // 4 actions: up, down, left, right

Self {

q_table,

position: (0, 0),

grid_size,

epsilon,

alpha,

gamma,

decay_rate,

}

}

/// Selects an action using epsilon-greedy exploration.

fn select_action(&self, rng: &mut rand::rngs::ThreadRng) -> usize {

if rng.gen::<f64>() < self.epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..4) // Random action

} else {

let state = self.state_index();

self.q_table

.row(state)

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(b.1).unwrap())

.unwrap()

.0

}

}

/// Updates the agent's position based on the selected action.

fn update_position(&mut self, action: usize) {

let (x, y) = self.position;

self.position = match action {

0 => (x.saturating_sub(1), y), // Up

1 => ((x + 1).min(self.grid_size - 1), y), // Down

2 => (x, y.saturating_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (x, (y + 1).min(self.grid_size - 1)), // Right

_ => (x, y),

};

}

/// Updates the Q-value for the given state-action pair.

fn update_q_value(&mut self, action: usize, reward: f64, next_max_q: f64) {

let state = self.state_index();

let q_value = self.q_table[[state, action]];

self.q_table[[state, action]] += self.alpha * (reward + self.gamma * next_max_q - q_value);

}

/// Computes the state index based on the agent's position.

fn state_index(&self) -> usize {

self.position.0 * self.grid_size + self.position.1

}

/// Decays the exploration rate to improve exploitation over time.

fn decay_epsilon(&mut self) {

self.epsilon = (self.epsilon * self.decay_rate).max(0.01);

}

}

/// Visualizes the agent's Q-table as a heatmap.

fn visualize_q_table(agent: &Agent, filename: &str) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (800, 800)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Q-Table Heatmap", ("sans-serif", 20))

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..agent.grid_size, 0..agent.grid_size)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

for x in 0..agent.grid_size {

for y in 0..agent.grid_size {

let state_index = x * agent.grid_size + y;

let max_q = agent.q_table.row(state_index).iter().cloned().fold(f64::MIN, f64::max);

// Use RGBColor instead of HSLColor for filling

let color_intensity = (max_q / 20.0).min(1.0).max(0.0);

let color = RGBColor(

(255.0 * (1.0 - color_intensity)) as u8,

(255.0 * (1.0 - color_intensity)) as u8,

255

);

chart.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

[(x, y), (x + 1, y + 1)],

color.filled(),

)))?;

}

}

Ok(())

}

fn simulate_independent_learning() {

let grid_size = 5;

let rewards = vec![(4, 4, 10.0), (2, 2, 5.0)];

let environment = GridEnvironment::new(grid_size, rewards);

let mut agent1 = Agent::new(grid_size, 0.9, 0.5, 0.9, 0.99);

let mut agent2 = Agent::new(grid_size, 0.9, 0.5, 0.9, 0.99);

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for episode in 0..500 {

agent1.position = (0, 0);

agent2.position = (4, 0);

for _ in 0..50 {

let action1 = agent1.select_action(&mut rng);

let action2 = agent2.select_action(&mut rng);

agent1.update_position(action1);

agent2.update_position(action2);

let reward1 = environment.get_reward(agent1.position.0, agent1.position.1);

let reward2 = environment.get_reward(agent2.position.0, agent2.position.1);

let next_max_q1 = agent1.q_table.row(agent1.state_index()).iter().cloned().fold(f64::MIN, f64::max);

let next_max_q2 = agent2.q_table.row(agent2.state_index()).iter().cloned().fold(f64::MIN, f64::max);

agent1.update_q_value(action1, reward1, next_max_q1);

agent2.update_q_value(action2, reward2, next_max_q2);

}

agent1.decay_epsilon();

agent2.decay_epsilon();

if episode % 50 == 0 {

println!(

"Episode {}: Agent 1 at {:?}, Agent 2 at {:?}",

episode, agent1.position, agent2.position

);

}

}

visualize_q_table(&agent1, "agent1_q_table.png").unwrap();

visualize_q_table(&agent2, "agent2_q_table.png").unwrap();

}

fn main() {

simulate_independent_learning();

}

The grid environment serves as the shared state space for the agents, where specific cells hold rewards that incentivize exploration. Each agent begins its journey at a predefined position on the grid and selects its actions—up, down, left, or right—based on an epsilon-greedy strategy. This strategy introduces a balance between exploring new states and exploiting known high-reward states. As agents navigate the environment, the rewards provided by the grid are based on their current positions, with some cells offering higher incentives than others. These interactions are governed by Q-learning, where agents update their Q-values using the Bellman equation. This equation factors in the immediate reward, the maximum estimated future Q-value from the subsequent state, and learning parameters such as the learning rate (alpha) and the discount factor (gamma). Over numerous episodes, the agents learn to identify and prioritize high-reward regions in the grid. With exploration rates gradually decaying, agents increasingly rely on exploitation, leading to more stable and refined policies.

13.3. Centralized Learning and Policy Optimization

Centralized learning in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) provides a robust framework for addressing the complexities of coordination, shared rewards, and non-stationarity in environments involving multiple interacting agents. Unlike decentralized approaches where agents learn independently, centralized learning leverages a global perspective to optimize agent policies collectively, aligning individual objectives with system-wide performance. This paradigm is particularly effective in tasks that require high levels of cooperation and coordination, such as swarm robotics, smart grids, and collaborative logistics. By utilizing a centralized critic or global objective function during the training phase, centralized learning ensures that agents develop strategies that account for the behaviors and contributions of their peers, mitigating the challenges posed by independent learning dynamics.

One of the primary advantages of centralized learning is its ability to handle non-stationarity, a common challenge in MAS where the environment evolves as agents adapt their strategies. In independent learning, agents experience this as shifting reward structures and state dynamics, making convergence difficult. Centralized learning addresses this by providing agents with a consistent global view during training, enabling them to optimize their policies based on a stable representation of the system. This approach is especially valuable in cooperative settings, where agents need to align their actions to achieve shared goals, such as maximizing the efficiency of a multi-robot warehouse or balancing energy distribution in a smart grid.

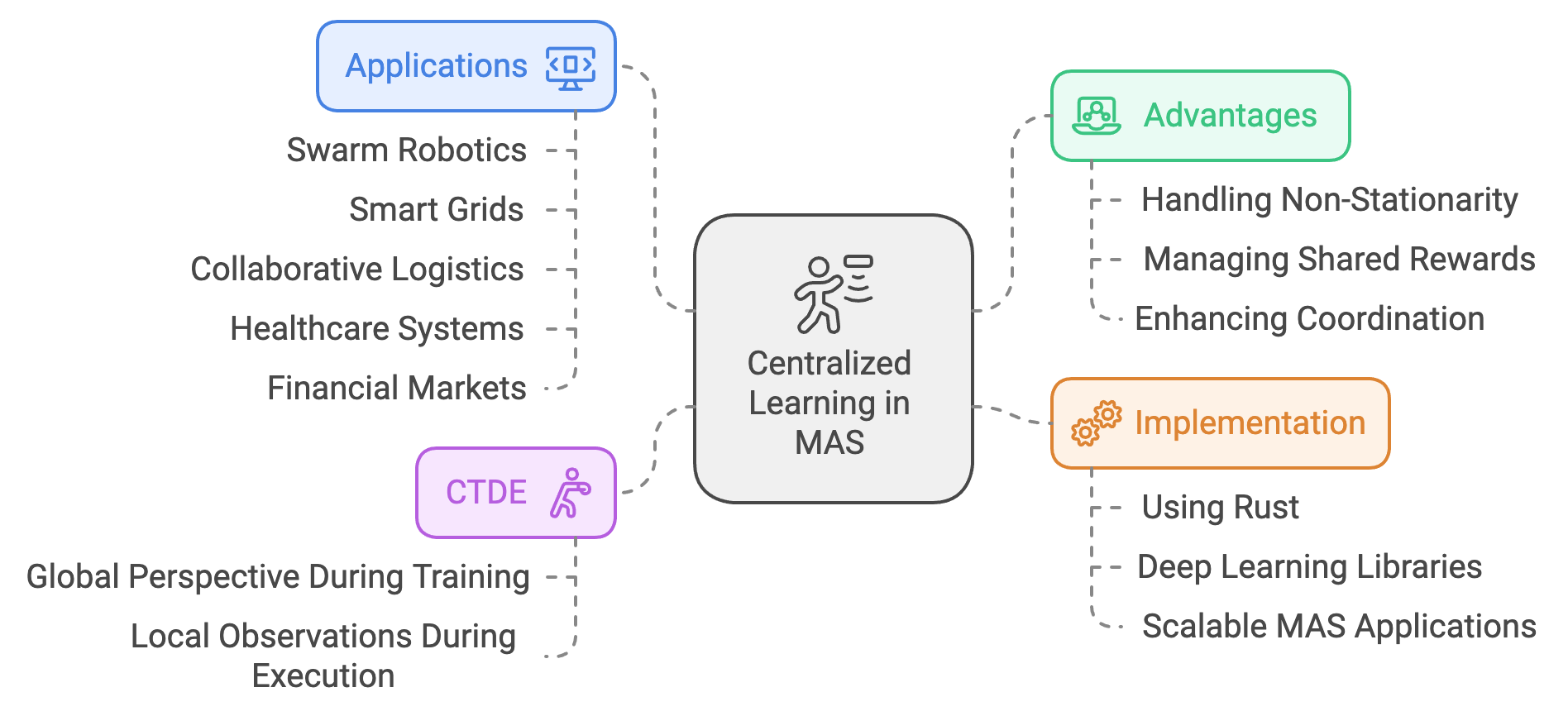

Figure 4: Scopes and Applications of Centralized Learning in MAS.

Another key advantage is the management of shared rewards in cooperative tasks. In MAS, rewards are often influenced by the collective actions of multiple agents, making it challenging to assign credit to individual contributions. Centralized learning employs mechanisms like value decomposition or counterfactual reasoning to decompose global rewards into individual components, ensuring that each agent receives feedback aligned with its role in achieving the shared objective. This not only improves learning efficiency but also prevents conflicts and fosters collaboration among agents. For instance, in a search-and-rescue operation involving drones, centralized learning can ensure that each drone is rewarded based on its specific contribution to the mission, such as locating survivors or mapping hazardous areas.

Centralized learning also enhances coordination by explicitly modeling the interdependencies among agents. By training agents with access to a centralized critic or shared information, centralized learning captures the joint dynamics of the system, enabling agents to anticipate and adapt to the actions of their peers. This results in more cohesive and efficient behaviors, particularly in tasks requiring precise synchronization. For example, in autonomous vehicle platooning, centralized learning ensures that vehicles coordinate their speeds and distances to minimize fuel consumption and enhance safety, even in dynamic traffic conditions.

Conceptually, centralized learning aligns with the paradigm of centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE). In this approach, agents are trained using a global perspective that accounts for the full state and action space of the system. Once trained, agents execute their policies independently, relying only on local observations and decentralized decision-making. CTDE combines the benefits of centralized training, such as improved coordination and stability, with the scalability and flexibility of decentralized execution. This hybrid approach is particularly valuable in real-world scenarios like swarm robotics, where centralized training can optimize collective behaviors, while decentralized execution ensures adaptability in the field.

From an implementation perspective, centralized learning demands robust computational frameworks capable of handling high-dimensional state and action spaces. Rust, with its focus on performance, concurrency, and memory safety, is well-suited for building scalable MAS applications. By leveraging libraries like tch for deep learning, Rust enables the efficient training of centralized critics and the simulation of large-scale agent interactions. For example, a Rust-based implementation of centralized learning in a smart grid could involve training a centralized critic to optimize energy distribution across multiple households and businesses. During execution, individual agents would rely on locally trained policies to adjust their energy consumption dynamically, ensuring grid stability and efficiency.

Another practical use case is in collaborative logistics, where centralized learning can optimize the coordination of delivery vehicles, warehouses, and distribution centers. By training a centralized critic to model the entire logistics network, agents can develop policies that minimize delivery times and costs while adapting to dynamic conditions like traffic or inventory shortages. Once deployed, agents operate independently, leveraging the learned policies to make real-time decisions that align with the overall system goals.

In swarm robotics, centralized learning ensures that agents operate cohesively in tasks requiring collective action, such as environmental monitoring or formation control. By training agents with access to a centralized perspective, the system can optimize strategies for maximizing coverage, avoiding collisions, and adapting to environmental changes. This approach is particularly useful in dynamic or adversarial settings, where independent learning might lead to fragmented or inefficient behaviors.

In healthcare systems, centralized learning facilitates coordination among agents representing hospitals, clinics, and public health authorities. By training agents with a global objective, such as minimizing patient wait times or optimizing resource allocation, centralized learning ensures that individual actions contribute to the overall efficiency of the system. For instance, in a vaccine distribution network, centralized learning can optimize the allocation of doses across regions, accounting for population density, transportation constraints, and storage requirements.

In financial markets, centralized learning enables agents to coordinate strategies for market making, arbitrage, or liquidity provision. By training agents with a centralized critic that models market dynamics, centralized learning ensures that individual trading strategies align with broader market stability objectives. This is particularly valuable in decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystems, where the actions of autonomous agents influence the overall integrity and efficiency of the system.

Centralized learning represents a powerful approach for addressing the challenges of coordination, shared rewards, and non-stationarity in MAS. By leveraging a global perspective during training, centralized learning enables agents to optimize their policies collectively, ensuring efficient and cohesive behaviors in complex, dynamic environments. Rust’s performance and scalability make it an ideal platform for implementing centralized learning frameworks, bridging the gap between theoretical principles and real-world applications. Whether in swarm robotics, smart grids, or collaborative logistics, centralized learning provides the tools to unlock the full potential of MAS in addressing some of the most pressing challenges in modern multi-agent systems.

Centralized learning leverages shared information across agents to optimize joint policies $\pi = (\pi_1, \pi_2, \dots, \pi_n)$, where $\pi_i(a_i \mid s)$ represents the probability of agent $i$ selecting action $a_i$ in state $s$. The global objective is to maximize the expected cumulative reward for all agents:

$$ \max_{\pi} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R(s_t, \boldsymbol{a}_t) \right], $$

where $R(s_t, \boldsymbol{a}_t)$ is the shared reward function for joint action $\boldsymbol{a}_t = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)$ taken in state $s_t$, and $\gamma$ is the discount factor.

The centralized critic $V(s)$ approximates the value function of the global reward:

$$ V(s) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R(s_t, \boldsymbol{a}_t) \mid s_0 = s \right]. $$

Advantage functions for individual agents are computed as:

$$ A_i(s, a_i) = Q_i(s, a_i) - V(s), $$

where $Q_i(s, a_i)$ is the state-action value function conditioned on the centralized critic:

$$ Q_i(s, a_i) = \mathbb{E} \left[ R(s_t, \boldsymbol{a}_t) + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) \mid s_t = s, a_{i,t} = a_i \right]. $$

Policy optimization uses gradient ascent to maximize the log-probabilities of actions weighted by their advantages:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\pi) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi(a_i \mid s; \theta) A_i(s, a_i) \right], $$

where $\theta$ represents the parameters of the policy.

Centralized learning provides significant advantages in cooperative MAS. A centralized critic facilitates learning in environments with shared rewards by modeling the dependencies between agents’ actions and the global reward. This alleviates the credit assignment problem, ensuring that agents align their policies with the overall objective.

Moreover, centralized critics address the non-stationarity inherent in independent learning by providing stable feedback based on the global state and joint actions. This stability accelerates convergence and reduces oscillatory behaviors in dynamic environments.

Case studies in swarm robotics, team-based games, and collaborative AI demonstrate the effectiveness of centralized learning. In swarm robotics, centralized critics optimize energy-efficient task allocation, while in team-based games, centralized policy gradients enhance coordinated strategies. Collaborative AI systems, such as multi-agent conversational bots, use centralized critics to ensure consistent and coherent interactions.

The following program showcases a centralized policy gradient model designed for multi-agent reinforcement learning tasks. The system comprises a CentralizedEnvironment to simulate states and rewards, and a CentralizedPolicy network that learns optimal actions for all agents using a shared policy. The environment is defined by a reward matrix that correlates agent actions to cumulative outcomes, while the policy network utilizes a neural architecture with fully connected layers, ReLU activations, and a softmax output to represent probabilities over possible actions. The model optimizes its policy using the Adam optimizer and computes gradients to adjust weights for improved performance over time.

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, Tensor, Device, Kind};

use tch::nn::OptimizerConfig;

/// Represents a centralized environment for multi-agent tasks.

struct CentralizedEnvironment {

rewards: Tensor,

}

impl CentralizedEnvironment {

fn new(state_size: usize, num_agents: usize) -> Self {

let rewards = Tensor::randn(&[state_size as i64, num_agents as i64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

println!(

"Environment initialized with state size: {}, num agents: {}.",

state_size, num_agents

);

Self { rewards }

}

/// Computes the reward for a given state and joint action.

fn compute_reward(&self, state: usize, actions: &[usize]) -> f64 {

actions

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(i, &a)| self.rewards.double_value(&[state as i64, i as i64]) * (a as f64))

.sum()

}

}

/// A centralized policy network for multi-agent systems.

struct CentralizedPolicy {

policy: nn::Sequential,

optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl CentralizedPolicy {

fn new(vs: &nn::VarStore, state_size: usize, action_size: usize) -> Self {

let policy = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs.root(), state_size as i64, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs.root(), 128, action_size as i64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.softmax(-1, Kind::Float));

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

println!("Centralized policy initialized.");

Self { policy, optimizer }

}

/// Computes action probabilities for a given state.

fn compute_policy(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.policy.forward(state)

}

}

/// Simulates a centralized policy gradient algorithm.

fn centralized_policy_gradient() {

let state_size = 4;

let num_agents = 2;

let action_size = 3;

let env = CentralizedEnvironment::new(state_size, num_agents);

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let mut centralized_policy = CentralizedPolicy::new(&vs, state_size, action_size);

let mut reward_history = Vec::new();

for episode in 0..1000 {

let state = Tensor::randn(&[1, state_size as i64], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu)).set_requires_grad(true);

let mut policy_output = centralized_policy.compute_policy(&state).squeeze();

// Normalize and handle invalid cases

let sum_output = policy_output.sum(Kind::Float);

policy_output = policy_output / sum_output;

if policy_output.isnan().any().int64_value(&[]) != 0 {

println!("NaN detected in policy output. Resetting to uniform probabilities.");

policy_output = Tensor::full(

&[action_size as i64],

1.0 / action_size as f64,

(Kind::Float, Device::Cpu),

);

}

let sum_output = policy_output.sum(Kind::Float); // Recompute after clamping

policy_output = policy_output.clamp(1e-6, 1.0 - 1e-6) / sum_output;

println!("Policy output: {:?}", policy_output);

let actions: Vec<usize> = policy_output

.multinomial(1, true)

.iter::<i64>()

.unwrap()

.map(|a| a as usize)

.collect();

let reward = env.compute_reward(0, &actions);

reward_history.push(reward);

let normalized_reward = reward

/ reward_history

.iter()

.copied()

.max_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.unwrap_or(1.0);

let log_probs = policy_output

.gather(

0,

&Tensor::of_slice(&actions.iter().map(|&a| a as i64).collect::<Vec<_>>()),

false,

)

.log();

let loss = -(log_probs.mean(Kind::Float) * Tensor::of_slice(&[normalized_reward as f32]));

centralized_policy.optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

if episode % 100 == 0 {

let avg_reward: f64 = reward_history.iter().copied().sum::<f64>() / reward_history.len() as f64;

reward_history.clear();

println!(

"Episode {}: Loss: {:.4}, Average Reward: {:.4}",

episode,

loss.double_value(&[]),

avg_reward

);

}

}

}

fn main() {

centralized_policy_gradient();

}

The centralized policy gradient algorithm begins by initializing an environment and a shared policy network. For each episode, the system samples a state and computes action probabilities using the policy network. Actions are then sampled from this probability distribution, and the environment calculates the corresponding reward based on the selected actions. The reward is normalized and used to compute a loss function comprising the log probabilities of selected actions. The optimizer backpropagates this loss to update the network's parameters, refining the policy. Over multiple episodes, the model learns to maximize cumulative rewards by improving its ability to predict optimal actions in various states.

13.4. Multi-Agent Credit Assignment

Credit assignment is one of the most critical challenges in Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), especially in cooperative or hybrid environments where agents collectively influence outcomes but receive a shared reward. The core goal of credit assignment is to attribute this shared reward appropriately to individual agents based on their contributions to the global objective. Effective credit assignment fosters the development of policies that not only optimize individual behaviors but also align these behaviors with the overall performance of the system. This alignment is essential in a wide array of applications, from swarm robotics to decentralized energy systems, and requires a combination of advanced techniques, thoughtful conceptual design, and robust implementation.

The complexity of credit assignment arises from the interconnected nature of agent actions in MAS. When multiple agents interact, their actions often have synergistic or antagonistic effects that make it challenging to isolate individual contributions. For example, in a drone swarm performing a search-and-rescue operation, the success of locating a target may depend on the coordinated efforts of multiple drones. Simply assigning equal credit to all agents would fail to account for the varying significance of their individual actions, such as one drone making a crucial discovery while others support navigation or communication. Such oversimplifications can lead to suboptimal learning, where agents fail to develop specialized or complementary roles.

Figure 5: Scopes and Applications of Credit Assignment in MAS.

In cooperative environments, effective credit assignment is essential for achieving fairness and efficiency. Fair credit attribution ensures that agents are rewarded in proportion to their contributions, which is particularly important in systems with diverse agent capabilities or roles. For instance, in a logistics network involving autonomous vehicles and warehouses, a vehicle delivering goods to a critical location deserves more credit than one transporting non-essential items. Fairness in credit assignment prevents agents from disengaging or adopting selfish strategies, fostering a more cohesive and efficient system.

In hybrid or mixed-motive environments, credit assignment becomes even more nuanced. Agents may simultaneously cooperate on some objectives while competing on others, requiring credit assignment mechanisms that balance these conflicting dynamics. For example, in decentralized energy markets, households may collaborate to stabilize the grid but compete for financial incentives. Effective credit assignment in such scenarios ensures that agents are incentivized to prioritize actions that benefit the system without sacrificing their individual goals.

Conceptually, credit assignment aligns with techniques such as counterfactual reasoning, value decomposition, and reward shaping. Counterfactual reasoning evaluates what the system’s outcome would have been had an individual agent taken a different action, providing a clearer picture of that agent’s impact. This approach is particularly useful in scenarios with complex interdependencies, such as smart grids or collaborative manufacturing, where the contribution of an agent's action might not be immediately apparent. Value decomposition techniques break down shared rewards into individual components, enabling agents to learn policies that align with both local and global objectives. Reward shaping modifies the reward signal to guide agents toward behaviors that benefit the system, addressing challenges like delayed rewards or sparse feedback.

Practical implementations of credit assignment in MAS benefit significantly from Rust's performance and safety features, which are critical for large-scale, real-time applications. Rust’s ability to handle concurrent processes makes it ideal for simulating multi-agent environments where agents interact dynamically. For example, in a Rust-based implementation of credit assignment in a swarm robotics system, each drone could independently compute its contribution to the shared mission outcome while ensuring efficient communication and resource management.

One compelling application of credit assignment is in traffic management systems, where autonomous vehicles must coordinate their actions to optimize traffic flow. By attributing credit to individual vehicles based on their contribution to reducing congestion or improving safety, credit assignment mechanisms encourage behaviors like yielding at intersections or maintaining optimal speeds. This ensures that the system as a whole benefits from smoother traffic flow while individual vehicles are rewarded for cooperative behavior.

In decentralized energy systems, credit assignment is crucial for balancing grid stability and fairness. Agents representing households or businesses adjust their energy consumption or production in response to shared rewards, such as financial incentives or grid stabilization metrics. Effective credit assignment ensures that agents contributing significantly to grid stability during peak demand periods are appropriately rewarded, fostering long-term engagement and system reliability.

Collaborative logistics also relies heavily on credit assignment to optimize resource allocation and delivery schedules. In a system where autonomous vehicles and warehouses work together to fulfill orders, assigning credit based on factors like delivery urgency, route efficiency, or inventory optimization ensures that the system operates at maximum efficiency. For example, a vehicle prioritizing urgent deliveries would receive higher credit than one delivering non-critical items, aligning individual actions with the overall logistics goals.

In healthcare systems, credit assignment plays a role in optimizing resource allocation across hospitals, clinics, and emergency services. Agents representing these entities might collaborate to minimize patient wait times or ensure equitable distribution of medical resources. Credit assignment mechanisms can reward agents based on metrics like patient outcomes or response times, encouraging a system-wide focus on efficiency and fairness.

The integration of advanced credit assignment techniques into MAS not only improves learning efficiency but also enhances the robustness and adaptability of multi-agent systems. By leveraging Rust for practical implementations, developers can create scalable, reliable systems capable of handling the complexities of credit assignment in diverse, real-world applications. Whether in autonomous transportation, energy markets, or collaborative robotics, effective credit assignment is a cornerstone of building intelligent, cooperative, and high-performing MAS.

In cooperative MAS, agents share a global reward $R(s, \boldsymbol{a})$, where $s$ is the state and $\boldsymbol{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n)$ is the joint action of $n$ agents. The challenge is to decompose $R(s, \boldsymbol{a})$ into individual contributions $r_i$ such that:

$$ R(s, \boldsymbol{a}) = \sum_{i=1}^n r_i(s, a_i, \boldsymbol{a}_{-i}), $$

where $\boldsymbol{a}_{-i}$ represents the actions of all agents except $i$.

Two prominent techniques for credit assignment are difference rewards and Shapley value-based methods.

Difference rewards measure the marginal contribution of an agent $i$ to the global reward by comparing $R(s, \boldsymbol{a})$ with the reward obtained by removing $i$ from the system. The difference reward for agent $i$ is defined as:

$$ D_i(s, \boldsymbol{a}) = R(s, \boldsymbol{a}) - R(s, \boldsymbol{a}_{-i}), $$

where $R(s, \boldsymbol{a}_{-i})$ is the reward when agent iii’s action is replaced with a baseline or null action. Difference rewards are particularly effective in encouraging agents to maximize their individual contributions without disrupting collective behavior.

The Shapley value provides a fair allocation of the global reward based on the marginal contributions of agents across all possible subsets. For agent iii, the Shapley value is:

$$ \phi_i = \frac{1}{n!} \sum_{S \subseteq N \setminus \{i\}} \frac{|S|! (n - |S| - 1)!}{n} \left[ R(s, S \cup \{i\}) - R(s, S) \right], $$

where $N = \{1, 2, \dots, n\}$ is the set of all agents, and $S$ is a subset of agents excluding $i$. The Shapley value guarantees a fair distribution of rewards based on the contributions of agents to various coalitions.

Credit assignment is essential for promoting cooperation and fairness in MAS. In cooperative settings, poorly designed reward mechanisms can lead to free-riding behavior, where some agents benefit from the actions of others without contributing meaningfully. Effective credit assignment ensures that each agent is incentivized to act in ways that benefit the global objective.

In hybrid MAS, where agents may have conflicting goals, credit assignment mechanisms help balance cooperative and competitive dynamics. Fair and scalable mechanisms, such as difference rewards and Shapley value-based methods, are critical for ensuring that learning algorithms converge to stable and effective policies.

However, implementing credit assignment in complex environments poses challenges. Computing the Shapley value, for instance, requires evaluating all possible coalitions, which is computationally expensive for large systems. Approximations and heuristics are often necessary to make these techniques scalable.

The following Rust implementation demonstrates reward decomposition using difference rewards and Shapley value-based methods. A cooperative task involving agents collecting resources in a grid environment is simulated. The code simulates a grid-based environment for cooperative multi-agent tasks, focusing on credit assignment through difference rewards. The GridEnvironment represents a grid containing resources with specific values, and agents navigate this grid to maximize the collective reward. Each agent's contribution to the global reward is evaluated by comparing the total reward with and without that agent's presence. The simulation iterates through episodes, randomly moving agents and computing their individual and collective rewards.

use rand::Rng;

/// Represents a grid environment for cooperative multi-agent tasks.

struct GridEnvironment {

grid_size: usize,

resource_positions: Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>, // (x, y, value)

}

impl GridEnvironment {

fn new(grid_size: usize, resource_positions: Vec<(usize, usize, f64)>) -> Self {

Self {

grid_size,

resource_positions,

}

}

/// Validates that all agent positions are within the grid.

fn validate_positions(&self, agent_positions: &[(usize, usize)]) -> bool {

agent_positions.iter().all(|&(x, y)| x < self.grid_size && y < self.grid_size)

}

/// Computes the global reward for a given set of agent positions.

fn compute_global_reward(&self, agent_positions: &[(usize, usize)]) -> f64 {

if !self.validate_positions(agent_positions) {

panic!("Agent positions out of bounds!");

}

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

for &(x, y, value) in &self.resource_positions {

if agent_positions.iter().any(|&(ax, ay)| ax == x && ay == y) {

total_reward += value;

}

}

total_reward

}

/// Computes the reward without a specific agent's contribution.

fn compute_reward_without_agent(

&self,

agent_positions: &[(usize, usize)],

excluded_agent: usize,

) -> f64 {

let filtered_positions: Vec<(usize, usize)> = agent_positions

.iter()

.enumerate()

.filter(|&(i, _)| i != excluded_agent)

.map(|(_, &pos)| pos)

.collect();

self.compute_global_reward(&filtered_positions)

}

}

/// Represents an agent in the grid environment.

struct Agent {

position: (usize, usize),

}

impl Agent {

fn new(position: (usize, usize)) -> Self {

Self { position }

}

}

fn simulate_credit_assignment() {

let grid_size = 5;

let resource_positions = vec![

(2, 2, 10.0),

(4, 4, 15.0),

(1, 3, 5.0),

];

let environment = GridEnvironment::new(grid_size, resource_positions);

let mut agents = vec![

Agent::new((0, 0)),

Agent::new((4, 0)),

Agent::new((0, 4)),

];

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for episode in 0..100 {

// Randomly move agents

for agent in &mut agents {

agent.position.0 = rng.gen_range(0..grid_size);

agent.position.1 = rng.gen_range(0..grid_size);

}

let agent_positions: Vec<(usize, usize)> =

agents.iter().map(|agent| agent.position).collect();

let global_reward = environment.compute_global_reward(&agent_positions);

let difference_rewards: Vec<f64> = agents

.iter()

.enumerate()

.map(|(i, _)| {

global_reward

- environment.compute_reward_without_agent(&agent_positions, i)

})

.collect();

println!(

"Episode {}: Global Reward: {:.2}, Difference Rewards: {:?}",

episode, global_reward, difference_rewards

);

}

}

fn main() {

simulate_credit_assignment();

}

The program defines a grid environment where resources are located at specified positions with associated values. Agents, represented by their positions, move randomly within the grid during each episode. The global reward is calculated as the sum of the values of resources accessed by the agents. To evaluate each agent's contribution, the difference reward is computed by subtracting the reward obtained without an agent from the global reward. This process helps in assigning credit to agents based on their individual impact on the collective reward, enabling effective multi-agent credit assignment.

Multi-agent credit assignment is a cornerstone of effective learning in MAS, addressing the challenges of cooperation, fairness, and scalability. Techniques such as difference rewards and Shapley value-based methods provide mathematical rigor and practical utility, enabling robust policy optimization in complex environments. The Rust implementation highlights how these techniques can be applied to real-world tasks, paving the way for scalable and fair multi-agent systems.

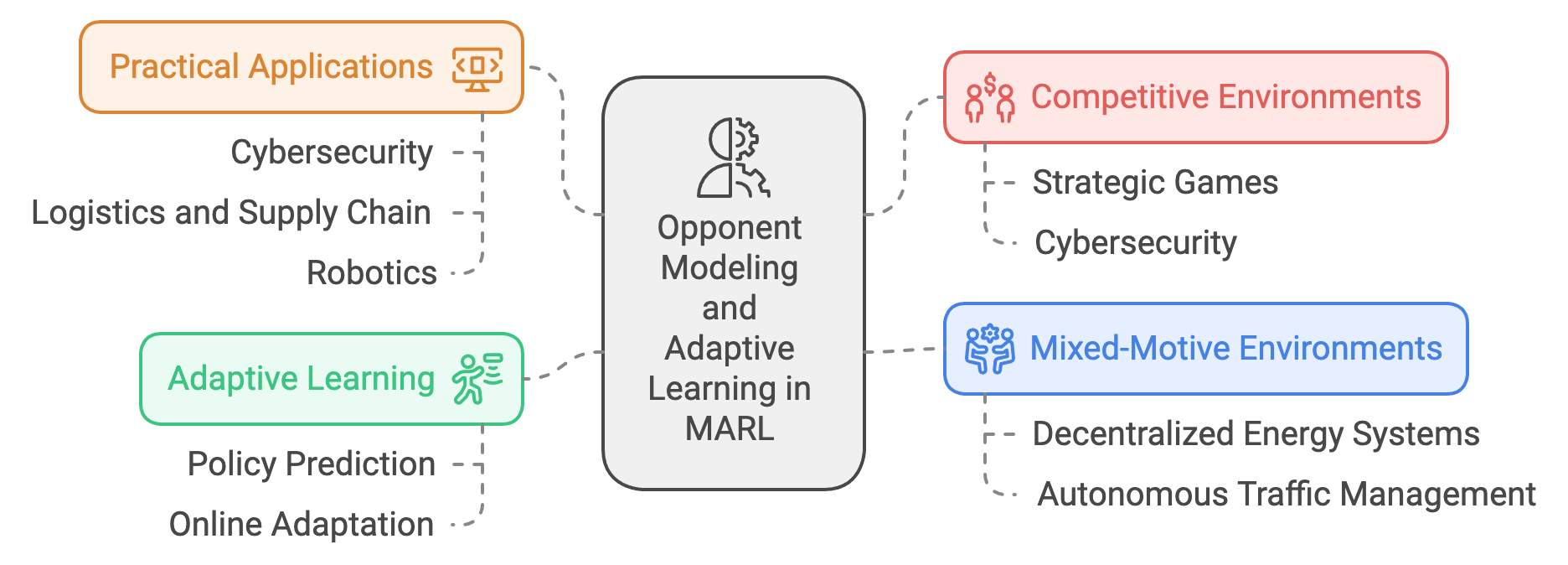

13.5. Opponent Modeling and Adaptive Learning

Opponent modeling and adaptive learning are integral to Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), particularly in environments where agents must navigate competition, adversarial interactions, or mixed-motive tasks. These techniques enable agents to predict and respond to the strategies of others, adapting their own behaviors dynamically to gain a strategic advantage. Whether in purely competitive scenarios like adversarial games or in hybrid settings where collaboration and competition coexist, opponent modeling and adaptive learning enhance an agent's ability to make informed decisions, improve coordination, and stabilize learning in non-stationary environments.

At the heart of opponent modeling is the idea that an agent’s environment is not static but influenced by the actions and strategies of other agents. Unlike traditional reinforcement learning, where the environment is typically assumed to be stationary, MARL involves constantly shifting dynamics as agents learn and adapt simultaneously. This non-stationarity can destabilize learning, leading to erratic policy updates or suboptimal outcomes. Opponent modeling mitigates these challenges by allowing agents to build predictive models of their counterparts, enabling more robust and anticipatory decision-making.

Figure 6: Scopes and Applications of Opponent Modeling and Adaptive Learning in MARL.

Opponent modeling is particularly valuable in competitive environments, where agents operate with conflicting objectives. For example, in strategic games like chess or poker, an agent’s success depends on its ability to anticipate the moves of its opponent and counter them effectively. By learning the patterns and tendencies of their adversaries, agents can develop strategies that exploit weaknesses or adapt to changing tactics. This is especially critical in adversarial tasks like cybersecurity, where defenders must anticipate and counteract evolving attack strategies. Opponent modeling allows defenders to predict potential threats based on historical behaviors, enabling proactive and effective responses.

In mixed-motive environments, where agents must balance collaboration and competition, opponent modeling facilitates nuanced interactions. For instance, in decentralized energy systems, households may collaborate to stabilize the grid but compete for financial incentives. By modeling the strategies of others, agents can identify opportunities for mutually beneficial actions, such as load balancing, while avoiding conflicts that could destabilize the system. This ability to adapt dynamically to the behaviors of others ensures that agents can navigate complex trade-offs between self-interest and collective goals.

Adaptive learning complements opponent modeling by enabling agents to adjust their strategies in response to the observed behaviors of others. This involves not only reacting to immediate changes but also identifying long-term patterns and trends in opponent strategies. For example, in financial markets, trading agents operate in highly dynamic environments where the strategies of other participants constantly evolve. Adaptive learning allows these agents to refine their trading strategies based on market signals and the actions of competitors, ensuring resilience and competitiveness in volatile markets.

One of the key advantages of adaptive learning is its ability to enhance coordination and stability in multi-agent systems. In scenarios like autonomous traffic management, where vehicles must navigate shared roadways, adaptive learning enables agents to adjust their driving strategies based on the behaviors of other vehicles. For instance, if a vehicle detects aggressive driving patterns in its vicinity, it can adapt by adopting more defensive maneuvers to maintain safety. Similarly, in swarm robotics, adaptive learning allows agents to coordinate their actions dynamically, ensuring efficient task execution even in unpredictable environments.

Conceptually, opponent modeling and adaptive learning align with techniques such as policy prediction, behavior cloning, and online adaptation. Policy prediction involves learning a model of an opponent’s policy, enabling the agent to anticipate future actions based on observed behaviors. Behavior cloning allows agents to mimic effective strategies demonstrated by others, which can be particularly useful in cooperative tasks or when dealing with opponents that exhibit optimal behavior. Online adaptation, on the other hand, equips agents with the ability to refine their strategies in real-time, ensuring responsiveness to rapidly changing conditions.

From a practical perspective, implementing opponent modeling and adaptive learning in MARL requires computational frameworks that support dynamic updates and efficient simulations. Rust, with its focus on performance, concurrency, and safety, is well-suited for these tasks. Its ability to handle high-dimensional data and parallel processes makes it ideal for modeling interactions among multiple agents in complex environments. For example, in a Rust-based MARL simulation of autonomous vehicles, opponent modeling can be used to predict the driving strategies of other vehicles, while adaptive learning allows each vehicle to adjust its behavior dynamically to optimize traffic flow and safety.

Another practical application is in cybersecurity, where agents representing attackers and defenders engage in an ongoing strategic battle. Opponent modeling enables defenders to anticipate attack patterns based on historical data, while adaptive learning allows them to refine their countermeasures in response to evolving threats. This combination ensures that cybersecurity systems remain robust and effective even against sophisticated, adaptive adversaries.

In logistics and supply chain management, opponent modeling and adaptive learning optimize interactions among competing entities, such as suppliers, distributors, and retailers. For instance, a supplier might use opponent modeling to predict the pricing strategies of competitors, while adaptive learning allows it to adjust its own pricing dynamically to maintain competitiveness. Similarly, in collaborative logistics networks, agents can model the behaviors of their peers to identify opportunities for coordination, such as shared transportation routes or synchronized deliveries.

In robotics, opponent modeling enhances performance in competitive tasks like robotic soccer or adversarial navigation, where robots must outmaneuver opponents while achieving their objectives. Adaptive learning further improves these systems by enabling robots to refine their strategies based on real-time observations, ensuring agility and resilience in dynamic environments.

The integration of opponent modeling and adaptive learning into MARL systems transforms the way agents interact in complex, multi-agent environments. By enabling agents to predict and respond to the strategies of others, these techniques enhance decision-making, coordination, and resilience across a wide range of domains. Rust’s capabilities provide a robust foundation for implementing these advanced techniques, ensuring scalable and reliable solutions for real-world applications. Whether in autonomous systems, cybersecurity, or collaborative logistics, opponent modeling and adaptive learning are essential for unlocking the full potential of MARL in addressing the challenges of modern multi-agent interactions.

In MARL, each agent $i$ optimizes its policy $\pi_i$ in a shared environment influenced by the policies of other agents $\pi_{-i}$. Opponent modeling aims to estimate these policies $\pi_{-i}(a_{-i} \mid s)$, where $a_{-i}$ represents the joint actions of all agents except $i$. These estimates are then integrated into the learning process of agent $i$.

The estimated policy of opponents is expressed as:

$$ \hat{\pi}_{-i}(a_{-i} \mid s) = \arg\max_{\pi_{-i}} \mathbb{P}(a_{-i} \mid s; \pi_{-i}), $$

where $\mathbb{P}(a_{-i} \mid s; \pi_{-i})$ represents the likelihood of observing $a_{-i}$ in state sss under policy $\pi_{-i}$. This estimation is typically learned using a supervised learning approach or Bayesian inference based on observed state-action trajectories.

Agent $i$ incorporates the modeled opponent policies into its state-action value function $Q_i$:

$$ Q_i(s, a_i; \hat{\pi}_{-i}) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_i(s_t, a_t) \mid s_0 = s, a_{i,0} = a_i, \hat{\pi}_{-i} \right], $$

where $r_i(s_t, a_t)$ is the reward for agent $i$, $a_t = (a_i, a_{-i})$, and $\gamma$ is the discount factor.

Adaptive learning involves updating πi\\pi_iπi based on changes in $\hat{\pi}_{-i}$. For example, a policy gradient method for agent $i$ incorporating opponent modeling is expressed as:

$$\nabla_\theta J(\pi_i) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_i(a_i \mid s; \theta) Q_i(s, a_i; \hat{\pi}_{-i}) \right],$$

where $\theta$ represents the parameters of $\pi_i$.

Stability in adaptive learning is a key concern. Opponent modeling can induce oscillatory dynamics if agents overreact to transient changes in $\hat{\pi}_{-i}$. Techniques such as smoothing, regularization, and bounded learning rates are commonly used to mitigate instability.

Opponent modeling enhances agent performance in competitive tasks by anticipating adversarial strategies and countering them effectively. For example, in zero-sum games, agents can use modeled opponent policies to maximize their own payoffs while minimizing those of their adversaries.

In cooperative and mixed-motive tasks, opponent modeling supports coordination by predicting the actions of other agents and adjusting policies to align with collective objectives. Techniques such as counterfactual reasoning, where agents evaluate hypothetical scenarios based on alternative actions, further enhance strategic planning.

Meta-learning, or "learning to learn," is another advanced technique in adaptive learning. Agents train meta-policies that can rapidly adapt to changing opponent strategies, making them robust in dynamic environments.

Applications of opponent modeling span diverse domains, including competitive games, financial trading, cybersecurity, and autonomous vehicle interactions. In adversarial environments, such as intrusion detection or resource contention, opponent modeling allows agents to preemptively counter threats.

This Rust program simulates an adversarial task in a grid environment where an agent attempts to model and intercept an adversary aiming to reach a target position. The environment is represented by a grid, with a target position that rewards or penalizes the players based on who reaches it. The agent leverages a simple predictive policy to anticipate the adversary's moves and adapts its strategy dynamically through reinforcement learning.nts operate in a grid environment, where one agent acts as an adversary, and the other learns to predict and counter its strategy.

use ndarray::Array2;

use rand::Rng;

/// Represents a grid environment for adversarial tasks.

struct GridEnvironment {

target_position: (usize, usize), // The position the adversary aims to reach

}

impl GridEnvironment {

fn new(target_position: (usize, usize)) -> Self {

Self { target_position }

}

/// Computes the reward for a given position.

fn compute_reward(&self, agent_position: (usize, usize), adversary_position: (usize, usize)) -> f64 {

if agent_position == self.target_position {

10.0 // Agent intercepts adversary

} else if adversary_position == self.target_position {

-10.0 // Adversary reaches target

} else {

0.0

}

}

}

/// Represents an agent that models its opponent's policy.

struct Agent {

position: (usize, usize),

grid_size: usize,

policy: Array2<f64>, // Policy probabilities for each state-action pair

learning_rate: f64,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(grid_size: usize, initial_position: (usize, usize)) -> Self {