Chapter 14

Foundational MARL Algorithms

"An algorithm must be seen to be believed." — Donald Knuth

Chapter 14 explores the foundational algorithms that underpin Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), providing a comprehensive understanding of value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic methods. It delves into the mathematical principles behind these algorithms, including Q-value updates, policy gradients, and critic value estimation, while highlighting their application in cooperative, competitive, and mixed environments. The chapter also examines modern extensions, such as value decomposition networks and hierarchical policies, to address the challenges of non-stationarity, scalability, and credit assignment. With hands-on Rust-based implementations, this chapter bridges theoretical insights and real-world applications, equipping readers to build intelligent and scalable MARL systems.

14.1 Introduction to Foundational MARL Algorithms

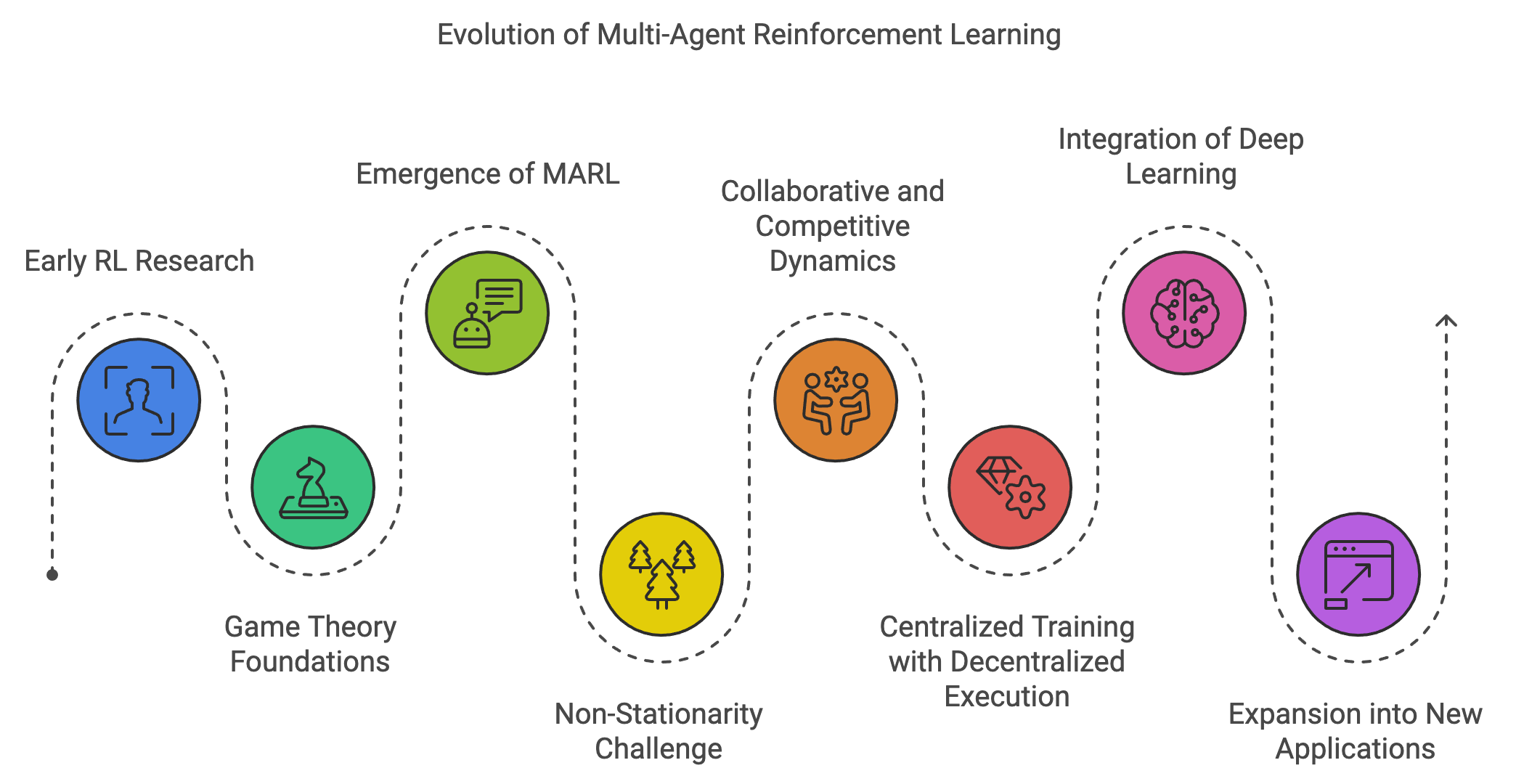

The evolution of Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) is deeply intertwined with the broader development of reinforcement learning (RL) and game theory. Early RL research focused on single-agent systems, where an agent interacted with a stationary environment to learn optimal policies through trial and error. While these foundational models demonstrated success in solving complex decision-making problems, they were limited to scenarios where only one agent operated in isolation. Real-world environments, however, often involve multiple autonomous agents interacting concurrently, influencing each other’s experiences and outcomes. This realization marked the beginning of the shift toward multi-agent systems and the development of MARL.

The theoretical groundwork for MARL was laid in the mid-20th century through the advent of game theory, particularly in the study of strategic interactions among rational decision-makers. Concepts like Nash equilibrium and zero-sum games provided a mathematical framework for analyzing multi-agent interactions. However, game theory assumed fully rational agents with complete information, limiting its applicability to dynamic, uncertain environments. With the advent of RL techniques in the late 1980s and 1990s, researchers began exploring ways to combine game-theoretic principles with learning mechanisms, leading to the emergence of MARL as a distinct field.

Figure 1: The historical evolution of MARL.

One of the early motivations for MARL was the need to address non-stationarity in multi-agent environments. Unlike single-agent systems, where the environment is typically static, multi-agent environments evolve dynamically as each agent updates its policy. This creates a moving target problem, where the optimal policy for one agent depends on the policies of others, which are simultaneously changing. Early models like Independent Q-Learning attempted to apply single-agent RL algorithms to multi-agent scenarios but struggled with instability and convergence issues due to this inherent non-stationarity.

Another key driver of MARL development was the recognition that many real-world problems involve collaborative and competitive dynamics. Tasks such as autonomous traffic management, drone swarm coordination, and financial market simulations require agents to balance self-interest with the need to cooperate or compete with others. Early MARL research introduced centralized training methods, where agents were trained collectively using global information, and decentralized execution, where agents acted independently using local observations. This centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) paradigm became a cornerstone of MARL research, enabling scalability while fostering coordination.

The integration of deep learning into MARL in the 2010s further accelerated its evolution, enabling agents to learn representations of high-dimensional state and action spaces. Models like Deep Q-Networks (DQN) were extended to multi-agent settings, leading to innovations such as Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) and QMIX. These models introduced techniques like value decomposition and shared critics, addressing challenges such as credit assignment and scalability. The combination of deep learning and MARL opened up new possibilities for solving complex tasks in dynamic, multi-agent environments, such as multi-robot systems, autonomous trading, and collaborative games.

The motivation for MARL lies in its ability to model and solve problems where multiple agents with potentially conflicting objectives must operate in shared environments. Traditional single-agent RL approaches fall short in capturing the complexity of such interactions, where agents influence and adapt to each other’s strategies. MARL provides the tools to handle these dynamics, offering solutions to challenges such as coordination, competition, and resource allocation. By enabling agents to learn behaviors that optimize both individual and collective goals, MARL has become a critical framework for advancing intelligent, adaptive systems across a wide range of domains.

As MARL continues to evolve, its applications are expanding into areas such as decentralized energy management, collaborative robotics, and large-scale simulations of social and economic systems. The integration of MARL with emerging technologies like edge computing, IoT, and large language models is further enhancing its relevance and potential. By addressing the challenges of non-stationarity, scalability, and coordination, MARL represents a transformative approach to building intelligent systems capable of operating effectively in complex, dynamic environments.

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) extends traditional reinforcement learning to environments involving multiple agents interacting concurrently. Each agent $i$ in the system has its state $s_i \in \mathcal{S}_i$, action $a_i \in \mathcal{A}_i$, and receives a reward $r_i \in \mathbb{R}$. The global environment is modeled by a joint state space $\mathcal{S} = \mathcal{S}_1 \times \mathcal{S}_2 \times \dots \times \mathcal{S}_N$ and a joint action space $\mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_1 \times \mathcal{A}_2 \times \dots \times \mathcal{A}_N$. The environment transitions are governed by the probability distribution $P(s' \mid s, \mathbf{a})$, where $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N)$ is the joint action, and $s'$ is the next joint state.

The primary objective in MARL is to optimize a joint policy $\pi = (\pi_1, \pi_2, \dots, \pi_N)$, where $\pi_i(a_i \mid s_i)$ is the policy of agent $i$, to maximize cumulative rewards. The optimization problem for each agent is formulated as:

$$J_i(\pi_i) = \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_i^t \mid \pi, P\right],$$

where $\gamma \in [0, 1)$ is the discount factor.

MARL algorithms often adopt one of three principal approaches: value-based, policy-based, or actor-critic methods. Value-based methods estimate a joint action-value function $Q(s, \mathbf{a})$ representing the expected cumulative reward for executing joint action $\mathbf{a}$ in state $s$. The update rule for the joint Q-function is defined as:

$$Q(s, \mathbf{a}) \leftarrow Q(s, \mathbf{a}) + \alpha \left[r + \gamma \max_{\mathbf{a}'} Q(s', \mathbf{a}') - Q(s, \mathbf{a})\right],$$

where $r$ is the shared reward, $\alpha$ is the learning rate, and $s'$ is the next state.

In policy-based methods, agents directly learn a parameterized policy $\pi_\theta(a_i \mid s_i)$. The parameters $\theta$ are optimized using the policy gradient theorem:

$$ \nabla_\theta J_i = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}\left[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_i \mid s_i) Q(s, \mathbf{a})\right]. $$

Actor-critic methods combine the strengths of value-based and policy-based approaches. An actor learns the policy $\pi_{\theta_i}(a_i \mid s_i)$, while a critic evaluates it using a value function $V_{\phi_i}(s_i)$. This structure reduces variance in policy updates and stabilizes learning.

Foundational MARL algorithms address key challenges in multi-agent environments. One critical issue is scalability. As the number of agents increases, the joint action space grows exponentially, making direct optimization computationally infeasible. Decentralized approaches, where each agent learns independently, mitigate this problem but can lead to suboptimal global performance due to lack of coordination.

Non-stationarity is another challenge. Since agents update their policies simultaneously, the environment appears dynamic and non-stationary from any individual agent’s perspective. Techniques such as centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) alleviate this by using centralized critics during training to stabilize learning while enabling decentralized policies during execution.

Partial observability further complicates MARL. Agents often lack access to the global state and must rely on local observations $o_i$. Strategies such as communication protocols, parameter sharing, and shared critics improve performance under these constraints.

Value-based methods like Value Decomposition Networks (VDN) and QMIX offer elegant solutions to these challenges. VDN decomposes the joint Q-function into individual components:

$$ Q(s, \mathbf{a}) = \sum_{i=1}^N Q_i(s_i, a_i), $$

where $Q_i$ represents the value function for agent $i$. QMIX extends this by learning a mixing network that approximates $Q(s, \mathbf{a})$ as a monotonic combination of individual value functions:

$$ Q(s, \mathbf{a}) = f(Q_1, Q_2, \dots, Q_N), $$

where $f$ is a learned function constrained to ensure monotonicity.

These techniques are widely applied in domains requiring agent coordination, such as cooperative robotics, resource allocation, and adversarial games.

The provided code implements a Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) environment using Rust, where multiple agents navigate a grid world to maximize their rewards. Each agent starts at a distinct position and can perform one of four actions—moving up, down, left, or right—while interacting with a grid containing random reward values. The system employs a Q-learning algorithm to train the agents over multiple episodes, adjusting their behavior through a balance of exploration and exploitation. The environment tracks each agent's position, updates rewards, and logs key metrics during training, providing a foundation for studying MARL dynamics.

use ndarray::{Array3, s};

use rand::Rng;

const GRID_SIZE: usize = 5;

const NUM_AGENTS: usize = 2;

const NUM_ACTIONS: usize = 4;

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

enum Action {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

}

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Agent {

position: (usize, usize),

}

struct MARLEnvironment {

grid: Array3<i32>,

agents: Vec<Agent>,

}

impl MARLEnvironment {

fn new() -> Self {

let mut grid = Array3::zeros((GRID_SIZE, GRID_SIZE, 1));

grid.map_inplace(|x| *x = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(0..10));

let agents = vec![

Agent { position: (0, 0) },

Agent { position: (GRID_SIZE - 1, GRID_SIZE - 1) },

];

MARLEnvironment { grid, agents }

}

fn step(&mut self, actions: &[Action]) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut rewards = vec![0; NUM_AGENTS];

for (i, action) in actions.iter().enumerate() {

let agent = &mut self.agents[i];

match action {

Action::Up => agent.position.1 = agent.position.1.saturating_sub(1),

Action::Down => agent.position.1 = (agent.position.1 + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1),

Action::Left => agent.position.0 = agent.position.0.saturating_sub(1),

Action::Right => agent.position.0 = (agent.position.0 + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1),

}

rewards[i] = self.grid[[agent.position.0, agent.position.1, 0]];

self.grid[[agent.position.0, agent.position.1, 0]] = 0;

}

rewards

}

}

fn q_learning(env: &mut MARLEnvironment, episodes: usize, alpha: f64, gamma: f64) {

let mut q_table = Array3::<f64>::zeros((GRID_SIZE, GRID_SIZE, NUM_ACTIONS));

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut steps = 0;

let mut total_rewards = vec![0; NUM_AGENTS];

println!("Episode {}: Starting training...", episode + 1);

while steps < 100 {

// Choose actions for all agents

let actions: Vec<Action> = env.agents.iter().map(|agent| {

let (x, y) = agent.position;

if rng.gen_bool(0.1) { // Explore

match rng.gen_range(0..NUM_ACTIONS) {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

}

} else { // Exploit

let action_index = q_table

.slice(s![x, y, ..])

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(b.1).unwrap())

.unwrap()

.0;

match action_index {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

}

}

}).collect();

// Step the environment

let rewards = env.step(&actions);

// Update Q-table and log details

for (i, reward) in rewards.iter().enumerate() {

let (x, y) = env.agents[i].position;

let action_index = match actions[i] {

Action::Up => 0,

Action::Down => 1,

Action::Left => 2,

Action::Right => 3,

};

let max_next_q = q_table.slice(s![x, y, ..]).iter().cloned().fold(0.0, f64::max);

// Update Q-value

q_table[(x, y, action_index)] += alpha * (*reward as f64 + gamma * max_next_q - q_table[(x, y, action_index)]);

// Accumulate total reward

total_rewards[i] += *reward;

// Print details

println!(

"Agent {} - Action: {:?}, Position: {:?}, Reward: {}, Q-value: {:.2}",

i,

actions[i],

env.agents[i].position,

reward,

q_table[(x, y, action_index)]

);

}

steps += 1;

}

println!(

"Episode {}: Total Rewards: {:?}",

episode + 1,

total_rewards

);

println!("Grid State after Episode:\n{:?}", env.grid);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut env = MARLEnvironment::new();

q_learning(&mut env, 1000, 0.1, 0.9);

}

The program defines an environment with a 3D grid (Array3) where agents move based on selected actions. Q-learning maintains a table of state-action values (q_table) to guide decisions, updated using temporal difference learning principles. During training, agents decide actions either by exploring randomly (to discover new states) or exploiting known information from the Q-table (to maximize reward). Each step updates the Q-table based on the observed rewards and the maximum expected future reward, reinforcing desirable behaviors. The code logs training details, such as actions, rewards, and Q-values, while summarizing performance at the end of each episode, offering insights into agent behavior and grid state evolution.

14.2. Value-Based MARL Algorithms

Value-based algorithms are foundational to Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), extending the core principles of single-agent Q-learning to environments where multiple agents interact and influence each other's learning processes. These methods revolve around learning value functions, which estimate the expected cumulative reward associated with specific state-action pairs. The extension of value-based methods to MARL introduces both opportunities and challenges, as the presence of multiple agents transforms the environment into a dynamic, non-stationary system where agent interactions are critical to overall performance.

The essence of value-based MARL lies in enabling agents to evaluate and optimize their actions in a shared environment. Unlike single-agent scenarios, where an agent learns value functions based on a stationary policy of the environment, in MARL, the actions of one agent affect the rewards and state transitions experienced by others. This interdependence introduces complexities in accurately estimating value functions and stabilizing learning. To address these challenges, two prominent value-based approaches have emerged: Independent Q-Learning (IQL) and Joint Action Learners (JAL).

Independent Q-Learning (IQL) represents a straightforward extension of single-agent Q-learning to multi-agent settings. Each agent independently learns its value function without explicit consideration of the actions or policies of other agents. This independence simplifies computation and makes IQL computationally scalable, particularly in large-scale systems. However, IQL assumes that the environment is stationary, an assumption that breaks down in MARL as other agents update their policies. This non-stationarity can lead to instability, where value functions fail to converge or become inconsistent. Despite this limitation, IQL remains useful in scenarios where agent interactions are minimal or can be approximated as independent, such as distributed resource allocation or task scheduling.

Joint Action Learners (JAL) take a more integrated approach by considering the joint actions of all agents in the system. Instead of learning value functions independently, JAL models the interactions among agents by evaluating the expected rewards of combined actions. This approach is particularly effective in cooperative environments, where the success of one agent often depends on the actions of others. By explicitly accounting for joint action spaces, JAL can optimize global objectives, such as maximizing team performance or achieving collective goals. However, the joint action space grows exponentially with the number of agents, making JAL computationally intensive in large-scale systems. Techniques like value decomposition and function approximation are often employed to mitigate this challenge, allowing JAL to remain tractable in complex environments.

Value-based MARL algorithms address several critical challenges inherent to multi-agent systems. One of the primary challenges is credit assignment, which involves determining the contribution of each agent’s action to the overall reward. In cooperative tasks, shared rewards make it difficult for agents to discern how their individual actions influenced the outcome. JAL addresses this by modeling joint actions, while advanced IQL implementations incorporate techniques like counterfactual reasoning or reward shaping to improve credit attribution.

Another challenge is scalability, especially in systems with large numbers of agents or high-dimensional state-action spaces. While IQL simplifies learning by focusing on individual policies, it may struggle in environments requiring tight coordination among agents. Conversely, JAL provides a more coordinated approach but requires computational techniques to handle the exponential growth of joint action spaces. Balancing these trade-offs is a central focus of research in value-based MARL.

Value-based methods are also pivotal in addressing exploration-exploitation trade-offs in MARL. The interdependent nature of agent actions can create uneven exploration, where certain regions of the state-action space are underexplored due to conflicting strategies. Algorithms like IQL and JAL are often augmented with exploration strategies that account for multi-agent dynamics, ensuring that agents collectively explore the environment effectively.

Practical applications of value-based MARL span a wide range of domains. In swarm robotics, value-based methods are used to coordinate the actions of drones or robots, enabling efficient task allocation and execution in dynamic environments. For instance, IQL might be employed to allow individual robots to independently optimize their paths in a warehouse, while JAL could be used in scenarios requiring formation control or collaborative exploration. Similarly, in autonomous traffic management, JAL can optimize joint actions at intersections or roundabouts, ensuring smooth traffic flow and minimizing delays.

In decentralized energy systems, value-based MARL algorithms enable households and businesses to optimize their energy consumption or production in response to pricing signals or grid conditions. IQL provides a scalable solution for individual agents, while JAL supports coordinated behaviors in demand-response programs, ensuring grid stability during peak demand periods.

Independent Q-Learning (IQL) is a decentralized approach where each agent $i$ independently learns its own Q-function $Q_i(s_i, a_i)$. The agent observes its local state $s_i$, takes an action $a_i$, and updates its Q-value based on the reward $r_i$ and the next state $s_i'$. The Q-value update rule for IQL is given by:

$$ Q_i(s_i, a_i) \leftarrow Q_i(s_i, a_i) + \alpha \left[ r_i + \gamma \max_{a_i'} Q_i(s_i', a_i') - Q_i(s_i, a_i) \right], $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $\max_{a_i'} Q_i(s_i', a_i')$ is the maximum estimated Q-value for the next state $s_i'$. While computationally efficient, IQL assumes a stationary environment, which is often violated in MARL due to simultaneous policy updates by multiple agents.

In contrast, Joint Action Learners (JAL) learn a single Q-function $Q(s, \mathbf{a})$ that accounts for the joint state $s$ and joint action $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N)$ of all agents. The Q-value update rule for JAL is:

$$Q(s, \mathbf{a}) \leftarrow Q(s, \mathbf{a}) + \alpha \left[ r + \gamma \max_{\mathbf{a}'} Q(s', \mathbf{a}') - Q(s, \mathbf{a}) \right],$$

where $r$ is a shared reward and $\mathbf{a}'$ represents all possible joint actions in the next state $s'$. While JAL explicitly models the interactions between agents, the joint action space grows exponentially with the number of agents, making it computationally prohibitive for large systems.

To address these challenges, value function decomposition methods like Value Decomposition Networks (VDN) and QMIX have been introduced. VDN decomposes the joint Q-function $Q(s, \mathbf{a})$ into agent-specific Q-functions $Q_i(s_i, a_i)$, assuming additive contributions:

$$ Q(s, \mathbf{a}) = \sum_{i=1}^N Q_i(s_i, a_i). $$

QMIX, on the other hand, uses a mixing network to approximate $Q(s, \mathbf{a})$ as a monotonic function of agent-specific Q-values, allowing for more flexible representations while maintaining central control during training.

Value-based MARL algorithms face two primary challenges: non-stationarity and scalability. Non-stationarity arises because each agent’s policy updates alter the environment dynamics for other agents, violating the stationarity assumption required for Q-learning. Centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE), as employed in QMIX, mitigates this issue by stabilizing the learning process during training. Scalability is another concern, especially in JAL, where the joint action space grows exponentially with the number of agents. Value decomposition techniques like VDN and QMIX address scalability by reducing the complexity of the learning process while preserving coordination among agents.

Applications of value-based MARL algorithms span cooperative and competitive tasks. In cooperative settings, such as resource allocation or multi-robot systems, agents must work together to maximize shared rewards. In competitive environments, like adversarial games, agents optimize their policies while anticipating the actions of opponents.

To illustrate the principles of value-based MARL, we implement both IQL and JAL in a cooperative grid-world environment using Rust. The code implements an Independent Q-Learning (IQL) algorithm for a Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) system, where multiple agents navigate a 2D grid environment. Each agent can move in one of four directions—up, down, left, or right—to collect rewards scattered across the grid. The agents learn independently, maintaining their own Q-tables to optimize their actions. The grid environment dynamically updates by depleting resources as agents collect them, while the Q-learning algorithm adjusts action-value estimates through episodes, balancing exploration and exploitation. demonstrates how the choice of value function—independent or joint—affects learning dynamics and performance.

use ndarray::{Array3, s};

use rand::Rng;

const GRID_SIZE: usize = 5;

const NUM_AGENTS: usize = 2;

const NUM_ACTIONS: usize = 4; // Actions: Up, Down, Left, Right

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

enum Action {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

}

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Agent {

position: (usize, usize),

}

struct GridWorld {

grid: Array3<i32>, // Grid values represent resources

agents: Vec<Agent>,

}

impl GridWorld {

fn new() -> Self {

let mut grid = Array3::zeros((GRID_SIZE, GRID_SIZE, 1));

grid.map_inplace(|x| *x = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(0..10)); // Random resource values

let agents = vec![

Agent { position: (0, 0) },

Agent { position: (GRID_SIZE - 1, GRID_SIZE - 1) },

];

GridWorld { grid, agents }

}

fn step(&mut self, actions: &[Action]) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut rewards = vec![0; NUM_AGENTS];

for (i, action) in actions.iter().enumerate() {

let agent = &mut self.agents[i];

match action {

Action::Up => agent.position.1 = agent.position.1.saturating_sub(1),

Action::Down => agent.position.1 = (agent.position.1 + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1),

Action::Left => agent.position.0 = agent.position.0.saturating_sub(1),

Action::Right => agent.position.0 = (agent.position.0 + 1).min(GRID_SIZE - 1),

}

rewards[i] = self.grid[[agent.position.0, agent.position.1, 0]];

self.grid[[agent.position.0, agent.position.1, 0]] = 0; // Deplete resource

}

rewards

}

}

fn iql(grid_world: &mut GridWorld, episodes: usize, alpha: f64, gamma: f64) {

let mut q_tables = vec![Array3::<f64>::zeros((GRID_SIZE, GRID_SIZE, NUM_ACTIONS)); NUM_AGENTS];

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut steps = 0;

println!("Episode {}: Starting training...", episode + 1);

while steps < 100 {

let actions: Vec<Action> = grid_world

.agents

.iter()

.map(|agent| {

let (x, y) = agent.position;

if rng.gen_bool(0.1) {

// Exploration

match rng.gen_range(0..NUM_ACTIONS) {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

}

} else {

// Exploitation

let q_table = &q_tables[0];

let action_index = q_table

.slice(s![x, y, ..])

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|(_, a), (_, b)| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap())

.unwrap()

.0;

match action_index {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

}

}

})

.collect();

let rewards = grid_world.step(&actions);

for (i, reward) in rewards.iter().enumerate() {

let (x, y) = grid_world.agents[i].position;

let action_index = match actions[i] {

Action::Up => 0,

Action::Down => 1,

Action::Left => 2,

Action::Right => 3,

};

let q_table = &mut q_tables[i];

let max_next_q = q_table.slice(s![x, y, ..]).iter().cloned().fold(0.0, f64::max);

q_table[(x, y, action_index)] += alpha * (*reward as f64 + gamma * max_next_q - q_table[(x, y, action_index)]);

}

steps += 1;

}

println!("Episode {} complete.", episode + 1);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut grid_world = GridWorld::new();

iql(&mut grid_world, 100, 0.1, 0.9);

}

This implementation highlights the differences between independent and joint value functions in learning cooperative tasks. By visualizing agent performance over episodes, we can analyze the impact of coordination and value decomposition on MARL dynamics. Advanced techniques like VDN and QMIX can further enhance the coordination in such tasks, balancing computational efficiency and learning effectiveness.

14.3. Policy-Based MARL Algorithms

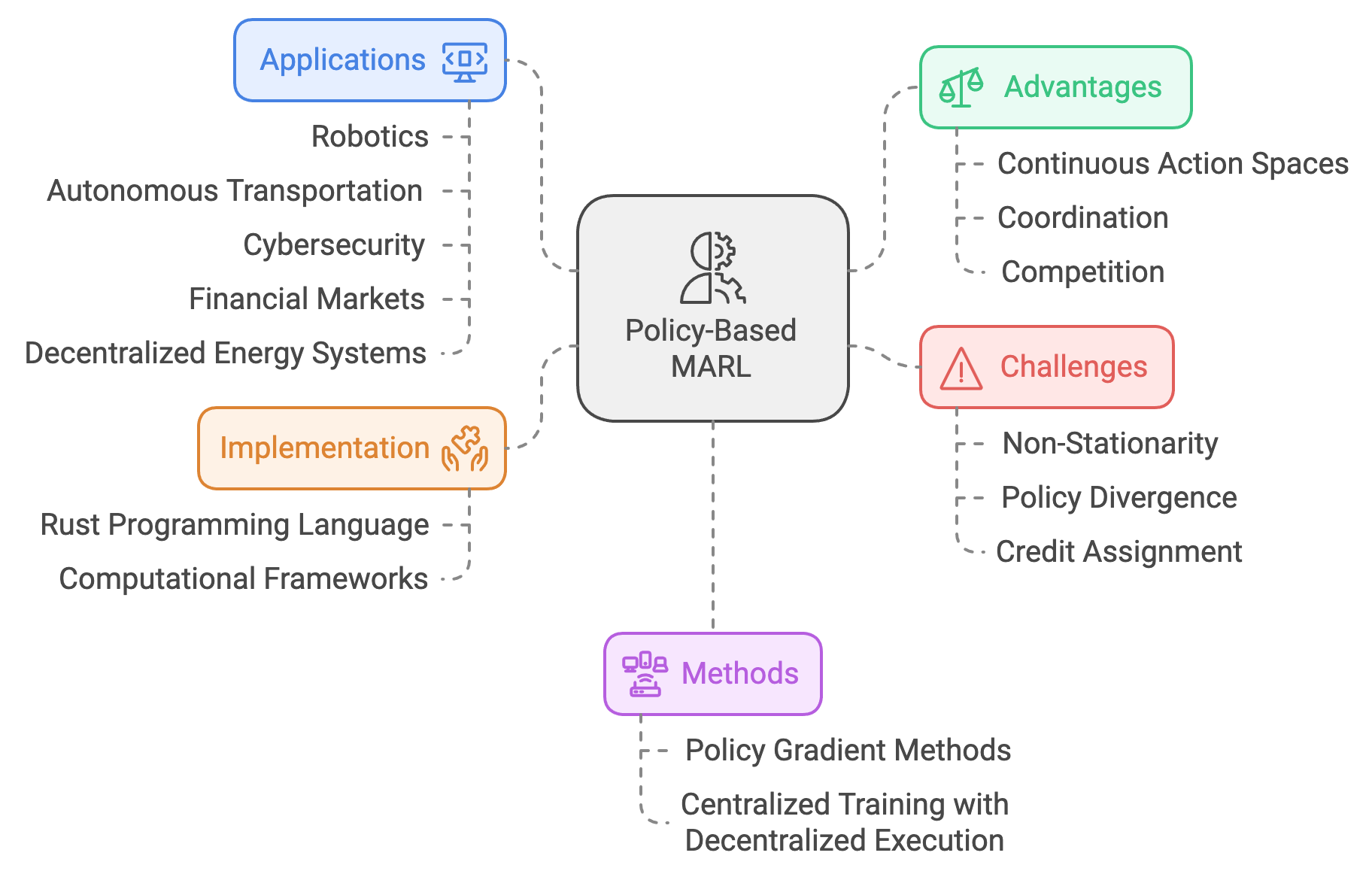

Policy-based algorithms play a pivotal role in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), offering a direct approach to optimizing agent behaviors by learning policies that map states to actions. Unlike value-based methods, which rely on estimating value functions to guide decision-making, policy-based algorithms focus on refining the policy itself. This makes them especially effective in environments with continuous action spaces, complex dynamics, or tasks requiring explicit modeling of strategies for coordination or competition. These qualities position policy-based methods as a cornerstone of MARL, enabling agents to navigate intricate multi-agent interactions with precision and adaptability.

The primary advantage of policy-based algorithms lies in their ability to handle continuous action spaces, which are common in many real-world applications. For instance, in robotics, agents often operate in environments where actions, such as motor controls or joint angles, are inherently continuous. Value-based methods struggle in these scenarios due to the difficulty of discretizing high-dimensional action spaces effectively. Policy-based methods overcome this limitation by parameterizing the policy as a continuous function, allowing agents to learn directly in the action space without discretization. This results in smoother, more natural behaviors and reduces computational overhead.

Figure 2: Scopes and applications of Policy-based MARL.

In multi-agent settings, policy-based algorithms are particularly well-suited for tasks requiring coordination or competition. In cooperative scenarios, agents must align their actions to achieve shared objectives, such as drones working together to map a disaster area or autonomous vehicles coordinating traffic flow. Policy-based methods enable agents to learn policies that optimize group performance, fostering emergent cooperative behaviors. Conversely, in competitive environments like adversarial games or financial trading, agents use policy-based algorithms to adaptively counter their opponents, developing strategies that maximize their individual rewards while anticipating the actions of others.

A prominent category within policy-based algorithms is policy gradient methods, which optimize the policy by iteratively adjusting its parameters in the direction of higher expected rewards. These methods extend naturally to MARL, where each agent maintains its own policy and updates it based on its unique experiences. In cooperative settings, agents may share information during training to align their updates, enhancing overall system performance. In competitive scenarios, agents update their policies independently, learning to adapt dynamically to the strategies of their opponents.

Despite their advantages, policy-based methods face several challenges in MARL. One significant challenge is non-stationarity, which arises because the environment evolves as other agents simultaneously update their policies. This can destabilize learning, as the optimal policy for one agent changes continuously in response to the adaptations of others. Techniques such as centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) mitigate this issue by using a shared critic during training to stabilize updates, while enabling agents to execute their policies independently during deployment.

Another challenge is the potential for policy divergence, where updates lead to policies that perform poorly or are unstable. This is particularly problematic in competitive environments, where aggressive policy updates can escalate conflicts, leading to oscillatory or suboptimal behaviors. To address this, regularization techniques, such as entropy bonuses, are often used to encourage exploration and maintain policy diversity. This ensures that agents continue to explore promising strategies rather than prematurely converging on suboptimal ones.

Credit assignment is another critical challenge in MARL, particularly in cooperative tasks where rewards are shared among agents. Policy-based methods often integrate techniques like advantage estimation to help agents attribute rewards more accurately to their actions, improving the alignment of individual policies with group objectives. For example, in a logistics network, policies can be refined to ensure that agents prioritize actions that contribute meaningfully to overall efficiency, such as routing deliveries based on urgency or resource availability.

From a practical implementation perspective, policy-based algorithms in MARL demand computational frameworks capable of handling high-dimensional policies and dynamic interactions among agents. Rust, with its emphasis on performance, safety, and concurrency, provides an ideal platform for developing such systems. Rust’s ability to manage parallel processes efficiently ensures that multiple agents can train and execute their policies simultaneously, even in large-scale environments. Libraries like tch for deep learning enable the seamless implementation of neural network-based policies, while Rust’s strong type system and memory safety features ensure robustness in complex simulations.

One practical application of policy-based MARL is in robotics, where agents such as robotic arms or drones must execute precise, continuous actions in dynamic environments. Policy-based methods enable these agents to learn motion control policies that optimize performance metrics like speed, energy efficiency, or accuracy. For instance, a swarm of drones performing a coordinated search-and-rescue mission can use policy gradient methods to learn policies that balance individual exploration with collective coverage, ensuring efficient task completion.

In autonomous transportation, policy-based MARL facilitates the coordination of vehicles in shared road networks. Each vehicle learns a policy for navigating traffic while anticipating the actions of others, enabling safe and efficient movement through intersections or highways. Policy gradient methods allow vehicles to adapt dynamically to changing traffic patterns, reducing congestion and improving safety.

In cybersecurity, policy-based MARL supports the development of adaptive defense mechanisms against evolving threats. Agents representing intrusion detection systems or firewalls learn policies for identifying and mitigating attacks, optimizing their strategies in response to adversarial behaviors. This approach ensures that defense mechanisms remain robust and proactive, even in highly dynamic threat landscapes.

In financial markets, policy-based MARL enables trading agents to optimize their strategies in competitive environments. Agents learn policies for buying, selling, or holding assets based on market conditions, balancing individual profit goals with system-wide stability. For example, market makers can use policy gradient methods to adjust liquidity provision dynamically, ensuring resilience to market fluctuations.

Policy-based MARL also finds applications in decentralized energy systems, where agents representing households or businesses learn policies for energy consumption and production. By optimizing their actions in response to pricing signals or grid conditions, agents contribute to grid stability while maximizing individual utility. Policy-based methods enable more efficient integration of renewable energy sources, ensuring sustainable and adaptive energy management.

In conclusion, policy-based algorithms are a cornerstone of MARL, offering a versatile and powerful approach to optimizing agent behaviors in complex, multi-agent environments. By focusing directly on policy optimization, these methods address challenges in continuous action spaces, coordination, and competition, enabling agents to operate effectively in dynamic settings. Rust’s performance and scalability make it an ideal choice for implementing policy-based MARL systems, providing the tools needed to tackle real-world challenges in robotics, transportation, cybersecurity, and beyond. The continued evolution of policy-based algorithms promises to unlock new possibilities for intelligent, adaptive multi-agent systems.

In MARL, each agent $i$ learns a policy $\pi_{\theta_i}(a_i \mid s_i)$, parameterized by $\theta_i$, which maps its local state $s_i$ to a distribution over actions $a_i$. The objective for each agent is to maximize its expected cumulative reward:

$$J_i(\theta_i) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta_i}}\left[\sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_i^t \right],$$

where $\gamma \in [0, 1)$ is the discount factor. The policy gradient theorem extends to multi-agent settings, expressing the gradient of $J_i(\theta_i)$ as:

$$\nabla_{\theta_i} J_i = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta_i}}\left[\nabla_{\theta_i} \log \pi_{\theta_i}(a_i \mid s_i) A_i(s_i, a_i)\right],$$

where $A_i(s_i, a_i)$ is the advantage function. The advantage function measures the improvement of action $a_i$ over the expected value $V_i(s_i)$:

$$A_i(s_i, a_i) = Q_i(s_i, a_i) - V_i(s_i).$$

In practice, the advantage can be estimated using the reward-to-go, defined as:

$$\hat{A}_i(s_i, a_i) = \sum_{t'=t}^\infty \gamma^{t'-t} r_i^{t'} - V_i(s_i).$$

For MARL, Multi-Agent Policy Gradient (MAPG) methods extend the single-agent formulation by incorporating interactions between agents. Each agent’s policy gradient accounts for its own reward while indirectly considering the impact of others through the joint state-action dynamics. In cooperative scenarios, shared objectives and centralized critics are often used to stabilize learning.

Policy-based methods excel in scenarios requiring continuous action spaces, such as robotic control or fine-grained resource allocation. Unlike value-based methods, which discretize action spaces, policy-based approaches natively model continuous distributions, offering smoother and more precise learning.

However, policy gradient methods face significant challenges in MARL. Non-stationarity, caused by simultaneous updates to multiple agents’ policies, can destabilize training. Moreover, high variance in gradient estimates, common in policy-based methods, further complicates convergence. Techniques such as generalized advantage estimation (GAE) and centralized critics mitigate some of these issues.

Exploration is another critical aspect. To prevent premature convergence to suboptimal policies, entropy regularization is often added to the objective function. This encourages the policy to maintain sufficient randomness during training:

$$ J_i^\text{entropy}(\theta_i) = J_i(\theta_i) + \beta H(\pi_{\theta_i}), $$

where $H(\pi_{\theta_i})$ is the entropy of the policy, and $\beta > 0$ controls the strength of regularization. This term ensures that the agent explores diverse strategies, especially important in cooperative and adversarial tasks.

To demonstrate MAPG, we implement a neural network-based policy using the tch crate in Rust. The environment involves agents cooperating or competing in continuous action spaces, where the policy networks model Gaussian distributions over actions. The MAPG model implemented here leverages a policy gradient approach where each agent has its own neural network policy to interact with the environment. The architecture comprises multiple agents, each defined with a policy network consisting of two fully connected layers. The input layer maps the state space (4 dimensions) to a hidden layer of 64 neurons, followed by a ReLU activation. The output layer produces probabilities over action space (2 dimensions) using the Log-Softmax activation. The agents optimize their policies using the Adam optimizer and employ techniques like gradient clipping for stable updates.

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.16.1"

plotters = "0.3.7"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Tensor};

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::fs;

const STATE_DIM: i64 = 4;

const ACTION_DIM: i64 = 2;

const NUM_AGENTS: usize = 2;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Agent {

policy_net: nn::Sequential,

optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(vs: &nn::VarStore) -> Self {

let policy_net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "layer1", STATE_DIM, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs.root() / "layer2", 64, ACTION_DIM, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.log_softmax(-1, tch::Kind::Float));

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

Self {

policy_net,

optimizer,

}

}

fn select_action(&self, state: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let state = state.to_device(tch::Device::Cpu);

let log_probs = self.policy_net.forward(&state);

let actions = log_probs

.exp()

.multinomial(1, true)

.squeeze_dim(1);

(actions, log_probs)

}

fn update_policy(&mut self, log_probs: &Tensor, rewards: &Tensor, vs: &nn::VarStore) -> f64 {

let safe_log_probs = log_probs.detach().set_requires_grad(true);

let loss = -(safe_log_probs * rewards).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

let loss_value = loss.double_value(&[]);

self.optimizer.zero_grad();

loss.backward();

self.clip_gradients(vs, 1.0);

self.optimizer.step();

loss_value

}

fn clip_gradients(&self, vs: &nn::VarStore, max_norm: f64) {

let mut total_norm2: f64 = 0.0;

for (_, param) in vs.variables() {

if param.grad().defined() {

let grad_norm2 = param.grad().norm_scalaropt_dim(2.0, &[], false).double_value(&[]).powi(2);

total_norm2 += grad_norm2;

}

}

let total_norm = total_norm2.powf(0.5);

if total_norm > max_norm {

let clip_coef = max_norm / (total_norm + 1e-6);

for (_, param) in vs.variables() {

if param.grad().defined() {

let mut grad = param.grad();

let _ = grad.f_mul_scalar_(clip_coef);

}

}

}

}

}

fn simulate_environment(states: &Tensor, actions: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let next_states = states + actions.to_kind(states.kind());

let rewards = actions.sum_dim_intlist(&[1][..], false, tch::Kind::Float);

(next_states, rewards)

}

fn plot_training_metrics(

episodes: &[usize],

rewards: &[f64],

losses: &[f64]

) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Ensure output directory exists

fs::create_dir_all("output")?;

// Plotting rewards

let root = BitMapBackend::new("output/rewards.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Training Rewards", ("Arial", 30).into_font())

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(

episodes[0] as f64..(*episodes.last().unwrap()) as f64,

*rewards.iter().min_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap()..

*rewards.iter().max_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap()

)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart.draw_series(

LineSeries::new(

episodes.iter().zip(rewards).map(|(x, y)| (*x as f64, *y)),

&RED

)

)?;

// Plotting losses

let root = BitMapBackend::new("output/losses.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Training Losses", ("Arial", 30).into_font())

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(

episodes[0] as f64..(*episodes.last().unwrap()) as f64,

*losses.iter().min_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap()..

*losses.iter().max_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap()

)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart.draw_series(

LineSeries::new(

episodes.iter().zip(losses).map(|(x, y)| (*x as f64, *y)),

&BLUE

)

)?;

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(tch::Device::Cpu);

let mut agents: Vec<Agent> = (0..NUM_AGENTS)

.map(|_| Agent::new(&vs))

.collect();

let episodes = 20000;

let gamma = 0.99;

// Tracking vectors for plotting

let mut plot_episodes = Vec::new();

let mut plot_rewards = Vec::new();

let mut plot_losses = Vec::new();

println!("Episode | Avg Reward | Total Reward | Avg Loss");

println!("--------|------------|--------------|----------");

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut states = Tensor::rand(&[NUM_AGENTS as i64, STATE_DIM], (tch::Kind::Float, tch::Device::Cpu));

let mut episode_rewards = Vec::new();

let mut episode_log_probs = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..10 {

let mut actions_vec = Vec::new();

let mut log_probs_vec = Vec::new();

for (agent, state) in agents.iter_mut().zip(states.split(1, 0)) {

let (action, log_prob) = agent.select_action(&state);

actions_vec.push(action);

log_probs_vec.push(log_prob);

}

let actions = Tensor::stack(&actions_vec, 0);

let log_probs = Tensor::stack(&log_probs_vec, 0);

let (next_states, rewards) = simulate_environment(&states, &actions);

episode_rewards.push(rewards);

episode_log_probs.push(log_probs);

states = next_states;

}

let mut discounted_rewards = Vec::new();

let mut running_reward = Tensor::zeros(&[NUM_AGENTS as i64], (tch::Kind::Float, tch::Device::Cpu));

for reward in episode_rewards.iter().rev() {

running_reward = reward + gamma * &running_reward;

discounted_rewards.push(running_reward.shallow_clone());

}

discounted_rewards.reverse();

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

for (agent_idx, (agent, log_prob)) in agents.iter_mut()

.zip(episode_log_probs.iter())

.enumerate() {

let reward = &discounted_rewards[agent_idx];

let reward_value = reward.mean(tch::Kind::Float).double_value(&[]);

total_reward += reward_value;

let loss = agent.update_policy(log_prob, reward, &vs);

total_loss += loss;

}

let avg_reward = total_reward / NUM_AGENTS as f64;

let avg_loss = total_loss / NUM_AGENTS as f64;

// Print every 50 episodes

if episode % 50 == 0 {

println!(

"{:7} | {:10.4} | {:11.4} | {:8.4}",

episode, avg_reward, total_reward, avg_loss

);

// Store data for plotting

plot_episodes.push(episode);

plot_rewards.push(avg_reward);

plot_losses.push(avg_loss);

}

}

// Plot the metrics

plot_training_metrics(&plot_episodes, &plot_rewards, &plot_losses)?;

Ok(())

}

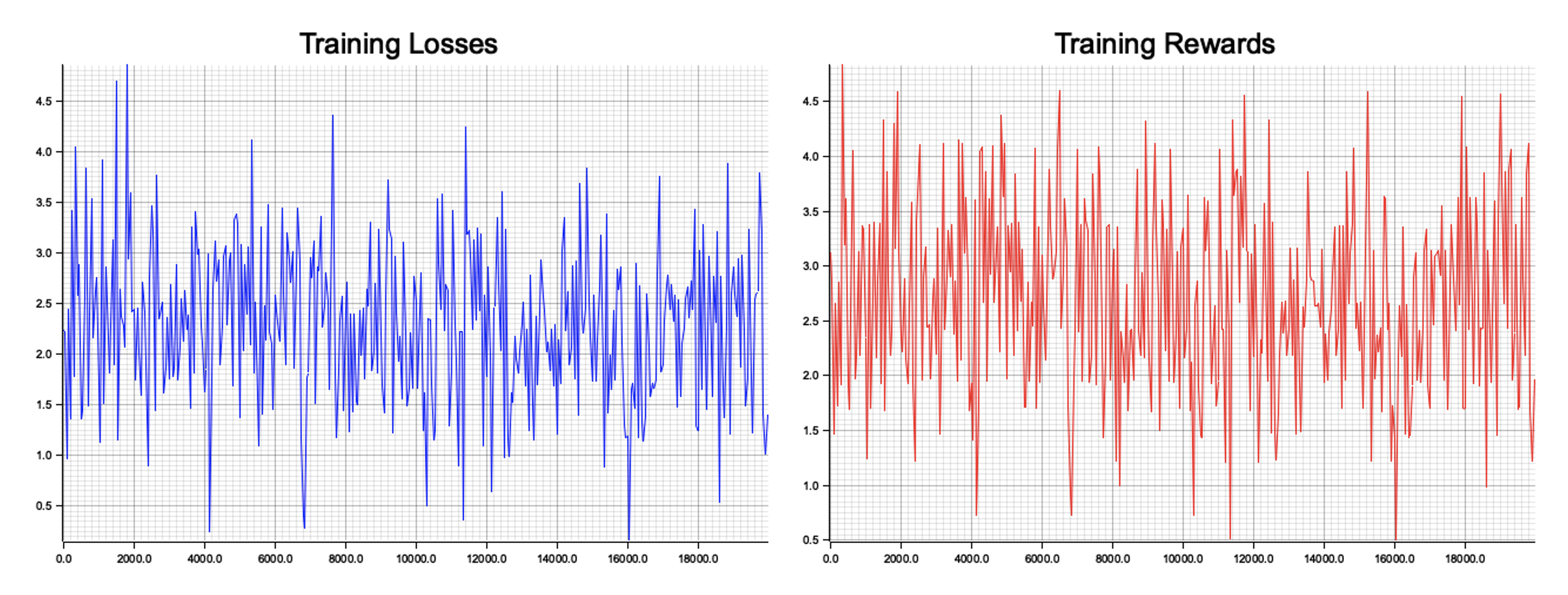

The code simulates a MAPG environment with two agents interacting over multiple episodes. Each agent selects actions based on the current state, calculated using the policy network. These actions are used to transition to new states and generate rewards, simulating an environment response. The policy is updated using discounted rewards and log probabilities of actions, ensuring agents learn to maximize long-term rewards. The simulation also includes functionality to compute and plot training losses and rewards, visualizing the agents' learning progress. Key steps include policy selection (select_action), reward calculation (simulate_environment), and optimization (update_policy).

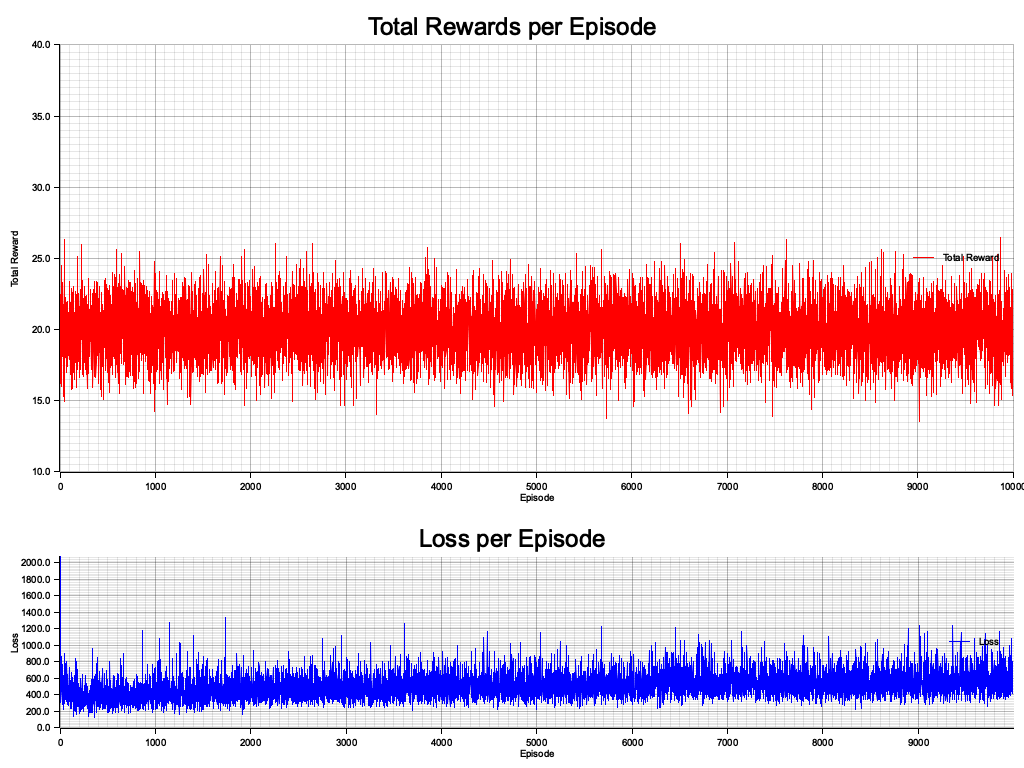

Figure 3: Plotters visualization of training losses and rewards in MAPG.

The visualizations depict the training dynamics of the MAPG system. The "Training Losses" chart reflects the fluctuations in policy optimization, indicating the model's effort to stabilize the learning process. The oscillations in losses highlight the inherent noise and instability in reinforcement learning, typical for policy gradient methods. The "Training Rewards" chart illustrates the reward trends over episodes, showing variability as agents explore and improve their policies. Overall, the charts suggest agents are actively learning, with gradual improvements as indicated by clustering of rewards and losses within narrower bounds over time.

Policy-based methods, as demonstrated through MAPG, provide a flexible and powerful framework for MARL. Their effectiveness in continuous action spaces and cooperative settings makes them invaluable in domains like robotics and strategic decision-making, though their challenges, such as handling non-stationarity, require careful consideration and tuning.

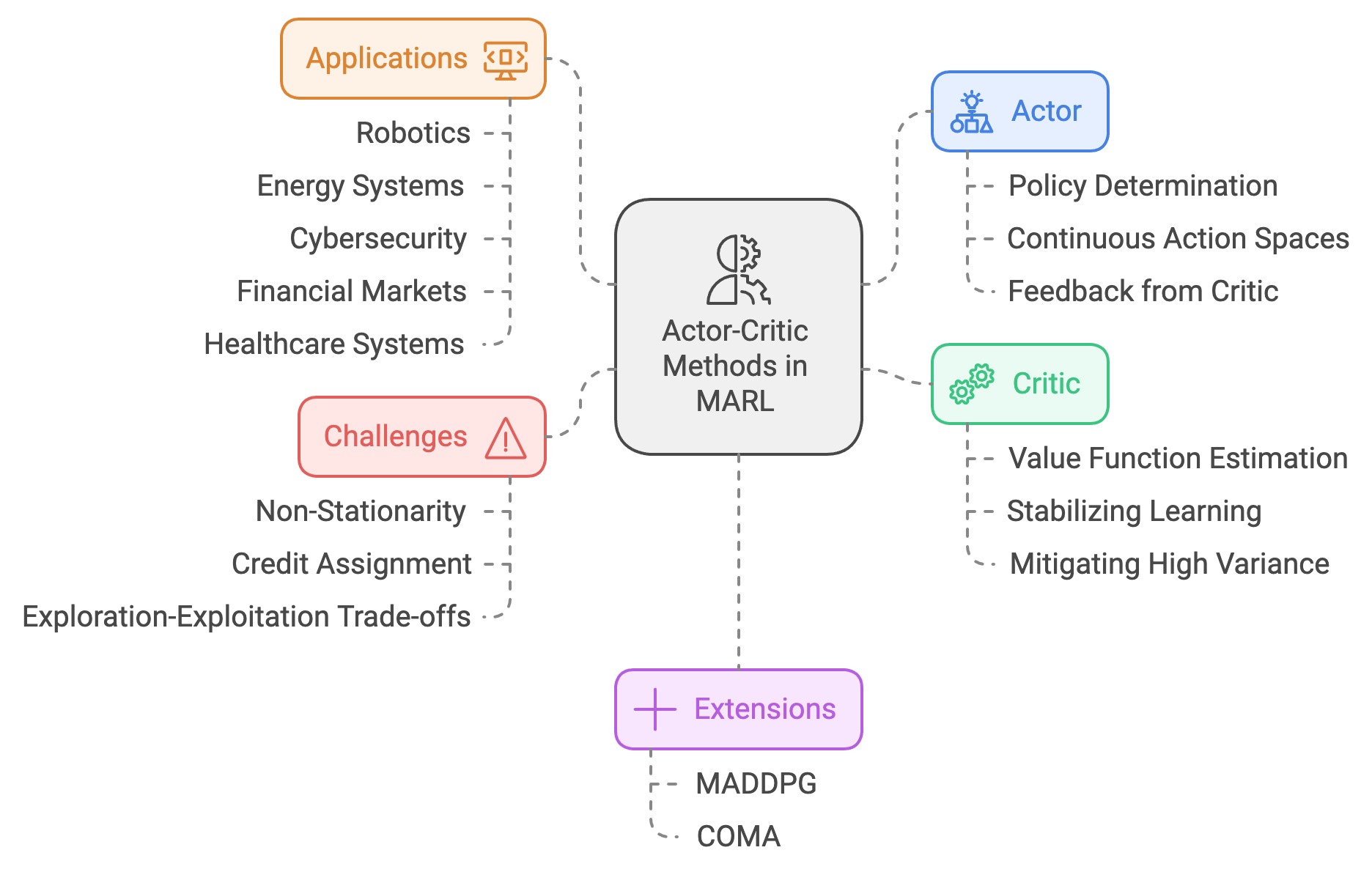

14.4. Actor-Critic Methods for MARL

Actor-critic methods represent a powerful hybrid approach in reinforcement learning, combining the strengths of policy-based (actor) and value-based (critic) methods into a cohesive framework. This dual-structured approach allows the actor to focus on directly optimizing the policy, mapping states to actions, while the critic evaluates the actions by estimating value functions, providing stability and guidance to the learning process. The versatility and robustness of actor-critic methods make them particularly well-suited for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL), where agents operate in dynamic, interdependent environments requiring coordination, competition, or both.

The actor in the actor-critic framework is responsible for determining the policy—how an agent selects its actions given its observations or state. This is particularly advantageous in MARL scenarios with continuous action spaces or complex decision-making tasks, where direct policy optimization is essential. The actor iteratively improves its policy using feedback from the critic, enabling agents to adapt their strategies in response to changing conditions and the behaviors of other agents.

Figure 4: Scopes and Applications for Actor-Critic Methods in MARL.

The critic complements the actor by evaluating the quality of the actions taken. It estimates a value function that captures the long-term rewards expected from a given state-action pair or policy. By providing feedback on the actor’s performance, the critic stabilizes learning, mitigating issues like high variance in policy updates. This stabilization is crucial in MARL, where the non-stationarity introduced by multiple concurrently learning agents can make it challenging for independent policy updates to converge reliably.

Actor-critic methods are particularly effective in addressing the unique challenges of MARL. One of these challenges is non-stationarity, which arises because the environment’s dynamics change as other agents update their policies. The critic helps counter this instability by providing a consistent evaluation of actions based on a shared understanding of the environment. For example, in cooperative settings like multi-robot systems, a centralized critic can evaluate the joint policy of all agents, ensuring that updates to individual actors align with the collective objective. Conversely, in competitive or mixed-motive environments, decentralized critics allow agents to learn independently while adapting to their opponents’ strategies.

Another critical advantage of actor-critic methods in MARL is their ability to address credit assignment in cooperative environments. When agents receive shared rewards, it becomes difficult to determine the contribution of each agent’s actions to the collective outcome. Actor-critic frameworks address this by using techniques like counterfactual reasoning or value decomposition, enabling the critic to assign rewards in a way that reflects individual contributions. This ensures that the actor learns policies that balance individual performance with group objectives, fostering collaboration and efficiency.

Actor-critic methods also excel in managing exploration-exploitation trade-offs, particularly in large, high-dimensional action spaces. The critic’s value function provides a structured way to guide exploration, encouraging the actor to prioritize actions that are likely to yield long-term rewards. This is especially useful in MARL scenarios where agents must explore effectively without interfering with each other’s learning processes. For instance, in autonomous traffic management, actor-critic methods enable vehicles to explore traffic patterns collaboratively, improving overall flow while minimizing individual risk.

The flexibility of actor-critic frameworks has led to several extensions tailored for MARL, such as Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) and Counterfactual Multi-Agent Policy Gradient (COMA). MADDPG combines deterministic policy gradients with centralized training and decentralized execution, allowing agents to learn policies that account for the behaviors of others while maintaining scalability. This approach is particularly effective in tasks requiring precise coordination, such as drone swarms or robotic manipulation. COMA uses counterfactual reasoning to improve credit assignment, enabling agents to evaluate their contributions to the team’s success more accurately. This makes COMA ideal for cooperative tasks where agents must work together to achieve complex objectives, such as collaborative manufacturing or resource allocation.

From a practical implementation perspective, actor-critic methods in MARL require computational frameworks that support dynamic interactions and efficient training across multiple agents. Rust, with its emphasis on concurrency, performance, and safety, provides an excellent foundation for developing such systems. Its ability to manage parallel processes ensures that agents can train and execute policies simultaneously, even in large-scale simulations. Libraries like tch for deep learning and rayon for parallel processing enable developers to implement actor-critic algorithms that scale effectively with the number of agents and the complexity of the environment.

For example, in a Rust-based implementation of MADDPG for a drone swarm, a centralized critic could be used during training to evaluate the joint actions of all drones, ensuring that their individual policies contribute to the overall mission. During execution, each drone would act independently, relying on its locally optimized policy to navigate and perform tasks. Similarly, in a logistics network, COMA could be implemented to optimize the coordination of autonomous vehicles and warehouses, ensuring efficient delivery schedules and resource allocation.

Applications of actor-critic methods span a wide range of industries. In robotics, actor-critic algorithms enable robots to perform complex tasks like object manipulation or collaborative assembly, where precise coordination and adaptive learning are essential. In energy systems, these methods facilitate the coordination of distributed energy resources, optimizing consumption and production to balance grid stability and economic incentives. In cybersecurity, actor-critic frameworks support the development of adaptive defense mechanisms, where agents representing firewalls or intrusion detection systems learn to counter evolving threats dynamically.

Actor-critic methods are also pivotal in financial markets, where trading agents must navigate competitive dynamics and optimize strategies in real-time. By learning policies that adapt to market conditions and the behaviors of other traders, actor-critic algorithms enable agents to maximize returns while contributing to market stability. Similarly, in healthcare systems, actor-critic methods optimize resource allocation across hospitals, clinics, and public health agencies, ensuring equitable and efficient delivery of care.

As summary, actor-critic methods represent a versatile and powerful approach to MARL, combining the strengths of policy-based and value-based learning to address the complexities of multi-agent environments. Their ability to handle non-stationarity, credit assignment, and exploration challenges makes them an essential framework for tasks requiring coordination, competition, or both. With Rust’s capabilities for high-performance and scalable implementations, actor-critic methods can drive innovation in diverse fields, from robotics and energy to finance and cybersecurity. As MARL continues to evolve, actor-critic frameworks will remain at the forefront of research and application, enabling intelligent, adaptive, and collaborative multi-agent systems.

In an actor-critic framework, the actor represents the policy $\pi_{\theta}(a \mid s)$, parameterized by $\theta$, which maps states $s$ to actions $a$. The critic estimates the value function $V_\phi(s)$ or the action-value function $Q_\phi(s, a)$, parameterized by $\phi$, which provides feedback to improve the actor’s policy. The learning objective is to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

$$J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_t \right],$$

where $\gamma$ is the discount factor. The actor’s policy parameters are updated using the policy gradient:

$$ \nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a \mid s) A(s, a) \right], $$

where $A(s, a)$ is the advantage function. The advantage can be estimated as:

$$A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s),$$

or directly using the reward-to-go approximation.

The critic updates its parameters by minimizing the temporal difference (TD) error for the value function:

$$L_\text{critic}(\phi) = \mathbb{E}\left[ \left( r + \gamma V_\phi(s') - V_\phi(s) \right)^2 \right].$$

In MARL, centralized critics are often used during training to address the non-stationarity introduced by other agents’ policies. A centralized critic $Q_\phi(s, \mathbf{a})$ conditions on the global state $s$ and joint action $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_N)$. The decentralized actor updates remain policy-specific to each agent for scalability and efficiency.

Extensions such as MADDPG (Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient) adapt actor-critic methods to continuous action spaces. In MADDPG, each agent $i$ has its own actor $\pi_{\theta_i}$ and critic $Q_{\phi_i}$, but the critic is centralized during training:

$$Q_{\phi_i}(s, \mathbf{a}) \leftarrow Q_{\phi_i}(s, \mathbf{a}) + \alpha \left( r_i + \gamma Q_{\phi_i}(s', \mathbf{a}') - Q_{\phi_i}(s, \mathbf{a}) \right),$$

where $\mathbf{a}'$ represents the joint actions from all agents in the next state.

Another extension, COMA (Counterfactual Multi-Agent Policy Gradients), introduces counterfactual reasoning to evaluate an agent’s contribution to the global reward. The counterfactual baseline for agent iii is computed as:

$$b_i(s, \mathbf{a}_{-i}) = \sum_{a_i} \pi_{\theta_i}(a_i \mid s) Q(s, (\mathbf{a}_{-i}, a_i)),$$

where $\mathbf{a}_{-i}$ denotes the actions of all agents except $i$. The policy gradient for COMA is adjusted as:

$$\nabla_{\theta_i} J_i = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta_i}}\left[\nabla_{\theta_i} \log \pi_{\theta_i}(a_i \mid s) \left( Q(s, \mathbf{a}) - b_i(s, \mathbf{a}_{-i}) \right)\right].$$

Actor-critic methods are particularly advantageous in mixed cooperative-competitive environments. They offer stability compared to purely policy-based methods and can handle both discrete and continuous action spaces. This makes them suitable for robotics, autonomous driving, and multi-robot systems, where agents must learn to cooperate or compete dynamically.

However, multi-agent actor-critic frameworks face challenges in credit assignment and policy stability. The credit assignment problem arises when determining each agent’s contribution to the global reward in cooperative tasks. Counterfactual reasoning, as used in COMA, provides a solution by isolating individual contributions. Policy stability is another issue, as the non-stationarity of the environment due to changing agent policies can destabilize training. Centralized critics alleviate this by incorporating global information during training.

Actor-critic methods find extensive applications across diverse domains where coordination, adaptability, and efficiency are critical. In robotics, they enable the precise coordination of multiple agents to perform shared tasks such as assembly, navigation, or object manipulation, fostering collaboration in dynamic environments. In autonomous driving, these methods help manage interactions between vehicles, ensuring safety and efficiency by enabling real-time adaptation to traffic conditions and the behaviors of other drivers. In multi-robot systems, actor-critic frameworks facilitate collaboration in complex operations such as exploration, search-and-rescue missions, and warehouse automation, where agents must work together seamlessly to achieve collective goals while optimizing individual contributions.

This code implements the Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) algorithm for cooperative reinforcement learning among multiple agents. Each agent has an actor network that predicts actions based on states and a target actor network used for stable training updates. The actor networks utilize a deep neural network with linear layers and ReLU activations to learn the policy. The agents interact with the environment by selecting actions, receiving rewards, and storing transitions in a shared replay buffer, enabling efficient sampling for training.

[dependencies]

tch = "0.12.0"

plotters = "0.3.7"

prettytable = "0.10.0"

rand = "0.8.5"

use tch::{

nn::{self, OptimizerConfig, VarStore},

Device, Kind, Tensor,

};

use rand::prelude::*;

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use prettytable::{Table, row}; // For table display

// Hyperparameters

const STATE_DIM: i64 = 16;

const ACTION_DIM: i64 = 4;

const NUM_AGENTS: usize = 4;

const HIDDEN_DIM: i64 = 256;

const BUFFER_CAPACITY: usize = 100_000;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99;

const TAU: f64 = 0.01;

const LR_ACTOR: f64 = 1e-3;

const MAX_EPISODES: usize = 100; // Increased to 100 episodes

const MAX_STEPS: usize = 5; // Adjusted for testing

// Replay Buffer

struct ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque<(Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)>,

}

impl ReplayBuffer {

fn new(capacity: usize) -> Self {

ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque::with_capacity(capacity),

}

}

fn add(&mut self, transition: (Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)) {

if self.buffer.len() == self.buffer.capacity() {

self.buffer.pop_front();

}

self.buffer.push_back(transition);

}

fn sample(

&self,

batch_size: usize,

device: Device,

) -> Option<(Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)> {

if self.buffer.len() < batch_size {

return None;

}

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let samples = self

.buffer

.iter()

.choose_multiple(&mut rng, batch_size);

let states = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.0.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let actions = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.1.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let rewards = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.2.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let next_states = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.3.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let dones = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.4.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

Some((states, actions, rewards, next_states, dones))

}

}

// Actor Network

struct ActorNetwork {

fc1: nn::Linear,

fc2: nn::Linear,

fc3: nn::Linear,

}

impl ActorNetwork {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, state_dim: i64, action_dim: i64) -> Self {

let fc1 = nn::linear(vs, state_dim, HIDDEN_DIM, Default::default());

let fc2 = nn::linear(vs, HIDDEN_DIM, HIDDEN_DIM, Default::default());

let fc3 = nn::linear(vs, HIDDEN_DIM, action_dim, Default::default());

ActorNetwork { fc1, fc2, fc3 }

}

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let x = state.apply(&self.fc1).relu();

let x = x.apply(&self.fc2).relu();

x.apply(&self.fc3).tanh()

}

}

// MADDPG Agent

struct MADDPGAgent {

actor: ActorNetwork,

target_actor: ActorNetwork,

actor_optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl MADDPGAgent {

fn new(state_dim: i64, action_dim: i64, device: Device) -> Self {

let actor_vs = VarStore::new(device);

let mut target_actor_vs = VarStore::new(device);

let actor = ActorNetwork::new(&actor_vs.root(), state_dim, action_dim);

let target_actor = ActorNetwork::new(&target_actor_vs.root(), state_dim, action_dim);

// Initialize target actor parameters to match the actor parameters

target_actor_vs.copy(&actor_vs).unwrap();

let actor_optimizer = nn::Adam::default()

.build(&actor_vs, LR_ACTOR)

.unwrap();

MADDPGAgent {

actor,

target_actor,

actor_optimizer,

}

}

fn select_action(&self, state: &Tensor, noise_scale: f64) -> Tensor {

let action = self.actor.forward(state);

let noise = Tensor::randn(&action.size(), (Kind::Float, action.device())) * noise_scale;

(action + noise).clamp(-1.0, 1.0)

}

fn soft_update(&mut self) {

tch::no_grad(|| {

self.target_actor.fc1.ws.copy_(

&(self.actor.fc1.ws.f_mul_scalar(TAU).unwrap()

+ self.target_actor.fc1.ws.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap()),

);

if let (Some(target_bs), Some(actor_bs)) = (

self.target_actor.fc1.bs.as_mut(),

self.actor.fc1.bs.as_ref(),

) {

let updated_bs = actor_bs

.f_mul_scalar(TAU)

.unwrap()

.f_add(&target_bs.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap())

.unwrap();

target_bs.copy_(&updated_bs);

}

// Repeat for fc2

self.target_actor.fc2.ws.copy_(

&(self.actor.fc2.ws.f_mul_scalar(TAU).unwrap()

+ self.target_actor.fc2.ws.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap()),

);

if let (Some(target_bs), Some(actor_bs)) = (

self.target_actor.fc2.bs.as_mut(),

self.actor.fc2.bs.as_ref(),

) {

let updated_bs = actor_bs

.f_mul_scalar(TAU)

.unwrap()

.f_add(&target_bs.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap())

.unwrap();

target_bs.copy_(&updated_bs);

}

// Repeat for fc3

self.target_actor.fc3.ws.copy_(

&(self.actor.fc3.ws.f_mul_scalar(TAU).unwrap()

+ self.target_actor.fc3.ws.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap()),

);

if let (Some(target_bs), Some(actor_bs)) = (

self.target_actor.fc3.bs.as_mut(),

self.actor.fc3.bs.as_ref(),

) {

let updated_bs = actor_bs

.f_mul_scalar(TAU)

.unwrap()

.f_add(&target_bs.f_mul_scalar(1.0 - TAU).unwrap())

.unwrap();

target_bs.copy_(&updated_bs);

}

});

}

}

// Training Function

fn train_maddpg(

agents: &mut Vec<MADDPGAgent>,

replay_buffer: &ReplayBuffer,

device: Device,

) -> Option<f64> {

if let Some((states, _actions, rewards, next_states, dones)) = replay_buffer.sample(BATCH_SIZE, device) {

let mut total_critic_loss = 0.0;

// Reshape tensors to [BATCH_SIZE, NUM_AGENTS, ...]

let rewards = rewards.view([BATCH_SIZE as i64, NUM_AGENTS as i64, -1]);

let dones = dones.view([BATCH_SIZE as i64, NUM_AGENTS as i64, -1]);

for (agent_idx, agent) in agents.iter_mut().enumerate() {

// Detach states and next_states to prevent shared computation graphs

let states_detached = states.detach();

let next_states_detached = next_states.detach();

// Extract the state and next_state for this agent

let state = states_detached.select(1, agent_idx as i64);

let next_state = next_states_detached.select(1, agent_idx as i64);

// Compute next action using the target actor

let next_action = agent.target_actor.forward(&next_state);

let next_action_mean = next_action.mean_dim(&[1i64][..], true, Kind::Float);

// Get rewards and dones for this agent

let reward = rewards.select(1, agent_idx as i64);

let done = dones.select(1, agent_idx as i64);

// ** Explicitly annotate the type **

let target_q_value: Tensor = &reward + GAMMA * (1.0 - &done) * &next_action_mean;

// Compute current action using the actor

let current_action = agent.actor.forward(&state);

let current_action_mean = current_action.mean_dim(&[1i64][..], true, Kind::Float);

// Calculate the loss (mean squared error)

let critic_loss = target_q_value.mse_loss(¤t_action_mean, tch::Reduction::Mean);

// Perform gradient descent

agent.actor_optimizer.zero_grad();

critic_loss.backward();

agent.actor_optimizer.step();

// Soft update of the target network

agent.soft_update();

// Accumulate critic loss

total_critic_loss += critic_loss.double_value(&[]);

}

let avg_critic_loss = total_critic_loss / agents.len() as f64;

Some(avg_critic_loss)

} else {

None

}

}

// Main Function

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let mut agents: Vec<MADDPGAgent> = (0..NUM_AGENTS)

.map(|_| MADDPGAgent::new(STATE_DIM, ACTION_DIM, device))

.collect();

let mut replay_buffer = ReplayBuffer::new(BUFFER_CAPACITY);

// Create a table to display metrics

let mut table = Table::new();

table.add_row(row!["Episode", "Total Reward", "Avg Critic Loss"]);

for episode in 0..MAX_EPISODES {

let mut states = Tensor::rand(&[NUM_AGENTS as i64, STATE_DIM], (Kind::Float, device));

let mut total_rewards = 0.0;

let mut episode_critic_loss = 0.0;

let mut steps_with_loss = 0;

for _ in 0..MAX_STEPS {

let actions = Tensor::stack(

&(0..NUM_AGENTS)

.map(|i| {

let state = states.get(i as i64);

agents[i].select_action(&state, 0.1)

})

.collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

);

// Expand actions to match state dimensions

let repeat_times = (STATE_DIM / ACTION_DIM) as i64;

let actions_expanded = actions.repeat(&[1, repeat_times]);

// Dummy environment interaction

let rewards = Tensor::ones(&[NUM_AGENTS as i64, 1], (Kind::Float, device));

let next_states = states.shallow_clone() + actions_expanded * 0.1;

let dones = Tensor::zeros(&[NUM_AGENTS as i64, 1], (Kind::Float, device));

total_rewards += rewards.sum(Kind::Float).double_value(&[]);

replay_buffer.add((

states.shallow_clone(),

actions.shallow_clone(),

rewards.shallow_clone(),

next_states.shallow_clone(),

dones,

));

states = next_states;

// Train the agents using the replay buffer

if let Some(critic_loss) = train_maddpg(&mut agents, &replay_buffer, device) {

episode_critic_loss += critic_loss;

steps_with_loss += 1;

}

}

// Calculate average critic loss for the episode

let avg_critic_loss = if steps_with_loss > 0 {

episode_critic_loss / steps_with_loss as f64

} else {

0.0

};

// Add the metrics to the table

table.add_row(row![

episode + 1,

format!("{:.2}", total_rewards),

format!("{:.4}", avg_critic_loss),

]);

}

// Print the table after all episodes

println!("{}", table);

}

During each episode, agents interact with a simulated environment, where they select actions using their actor networks and add Gaussian noise for exploration. The next states and rewards are computed based on the current state-action pairs. These transitions are stored in a replay buffer. During training, a batch of experiences is sampled from the buffer, and the actor networks are updated using the critic loss, which is computed as the mean squared error between the target Q-value and the current Q-value. The target Q-value is derived from the rewards and the predicted values of the next states using the target actor networks. The actor networks are updated via gradient descent, and the target networks are softly updated to improve stability.

The table provides a summary of each training episode, showing the episode number, the total reward accumulated by all agents, and the average critic loss. The total reward indicates how well the agents are performing their tasks collectively, while the average critic loss measures the discrepancy between the predicted and target Q-values. Lower critic loss values suggest better training convergence. Consistent improvements in the total reward across episodes indicate successful learning, while fluctuations in the critic loss may reflect challenges in the exploration-exploitation trade-off or high variance in sampled experiences.

Actor-critic methods can be evaluated by simulating mixed-motive games, where agents operate under cooperative and competitive objectives. For further improvement in the sample implementation code, visualizations using libraries like plotters in Rust can illustrate policy convergence, agent exploration, and reward trends over episodes. These insights are crucial for understanding the dynamics of multi-agent learning and optimizing the frameworks for real-world applications.

14.5. Modern Extensions of Foundational Algorithms

Modern advancements in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) have significantly expanded the capabilities of foundational algorithms, addressing their inherent limitations and enabling their application to increasingly complex and dynamic environments. These innovations are driven by the need for scalability, efficiency, and adaptability in systems involving numerous agents with diverse objectives and intricate interactions. By introducing techniques such as value decomposition, hierarchical learning, transfer learning, and meta-learning, modern MARL algorithms have evolved to tackle challenges like high-dimensional state spaces, sparse rewards, and dynamic task requirements, paving the way for transformative applications across industries.

Value decomposition is a key advancement that enhances scalability and learning efficiency in cooperative MARL. In cooperative environments, agents often share a collective reward, making it challenging to assign credit for individual contributions. Value decomposition techniques address this by decomposing the global value function into individual components that reflect each agent’s role in achieving the shared objective. Algorithms like QMIX and QTRAN exemplify this approach, enabling agents to optimize their policies independently while ensuring that their actions align with collective goals. This is particularly useful in scenarios like multi-robot systems, where agents must work together to complete tasks such as mapping or search-and-rescue. By reducing the complexity of the joint action space, value decomposition improves learning efficiency and ensures that individual agents can focus on their specific contributions.

Hierarchical learning introduces multi-level structures to MARL, allowing agents to operate at different levels of abstraction. This approach is especially beneficial in environments requiring complex decision-making over extended time horizons. For instance, a hierarchical MARL system for autonomous drones might involve a high-level policy for mission planning (e.g., covering specific areas) and low-level policies for navigation and obstacle avoidance. By decoupling decision-making processes, hierarchical learning reduces computational complexity and improves the interpretability of agent behaviors. It also facilitates transferability, as lower-level policies can often be reused across different tasks or environments, accelerating learning in new scenarios.

Transfer learning in MARL focuses on leveraging knowledge gained in one environment or task to accelerate learning in another. This is particularly valuable in dynamic systems where agents frequently encounter new challenges or environments. For example, in a logistics network, agents trained to optimize delivery routes in one city can apply their learned policies to another city with minimal retraining. Transfer learning not only reduces the computational resources required for training but also improves adaptability, enabling agents to respond effectively to changing conditions. Techniques such as policy distillation and shared representations are commonly used to facilitate the transfer of knowledge, ensuring that agents retain the essential elements of their previous experiences while adapting to new contexts.

Meta-learning, or learning to learn, represents a cutting-edge advancement in MARL, enabling agents to develop generalized strategies that can be quickly adapted to new tasks. Meta-learning focuses on training agents to optimize their learning processes, ensuring that they can acquire effective policies with minimal data or interactions. In MARL, this is particularly useful in environments with diverse or evolving objectives, such as multi-agent games or autonomous marketplaces. By learning meta-policies that encapsulate broad patterns of interaction, agents can adapt to new opponents, collaborators, or goals with significantly reduced training time. This makes meta-learning a powerful tool for enhancing the scalability and robustness of MARL systems.

Figure 5: Key advancements in MARL.

Modern MARL algorithms also integrate these techniques to address specific challenges, such as sparse rewards, where meaningful feedback is infrequent. Combining value decomposition with hierarchical learning, for instance, allows agents to decompose complex tasks into subtasks with more frequent rewards, guiding their exploration and improving convergence. Similarly, the integration of meta-learning with transfer learning enables agents to generalize across tasks while retaining the ability to adapt to specific scenarios, creating a balance between exploration and exploitation in diverse environments.

From an implementation perspective, these advancements demand computational frameworks capable of handling the complexity and scale of modern MARL systems. Rust’s performance, concurrency, and safety features make it an ideal choice for developing these algorithms. Libraries such as tch for neural network-based policy learning and rayon for parallel processing provide the necessary tools for training and deploying scalable MARL systems. For instance, a Rust-based implementation of QMIX could involve value decomposition networks trained in parallel across multiple agents, ensuring efficient resource utilization and rapid convergence.