Chapter 15

Deep Learning Foundations

"You don’t have to be a genius to solve big problems; you just have to care enough to solve them." — Fei-Fei Li

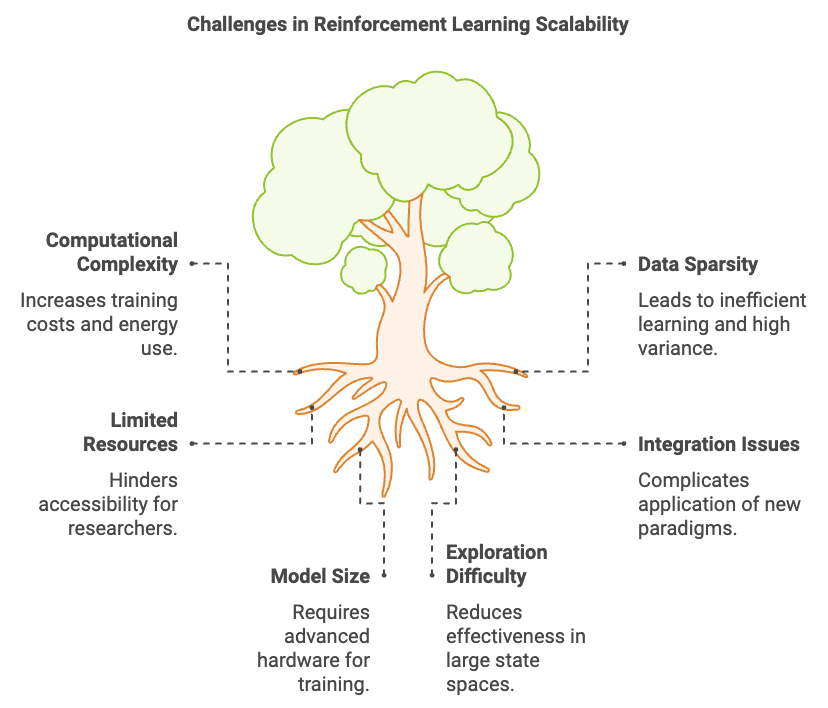

Chapter 15, Deep Learning Foundations, establishes the crucial link between deep learning and reinforcement learning (RL), offering a comprehensive guide to the principles, architectures, and implementations driving modern AI advancements. It begins with the mathematical formulation of neural networks, emphasizing their role as universal function approximators for extracting and learning hierarchical representations. Key architectural components such as feedforward, convolutional, recurrent networks, and Transformers are analyzed in the context of their applications to RL tasks, highlighting their suitability for spatial, sequential, and high-dimensional problems. Advanced optimization techniques, regularization strategies, and activation functions are presented to address challenges such as sparse rewards, overfitting, and non-stationarity in RL. The chapter also underscores Rust’s capabilities in building high-performance and memory-efficient deep learning systems, demonstrating cutting-edge implementations with the tch crate. By bridging theory with practice, this chapter prepares readers to apply deep learning effectively within RL frameworks, tackling complex, real-world tasks with state-of-the-art techniques.

15.1. Introduction to Deep Learning

The integration of deep learning into reinforcement learning (RL) represents a pivotal evolution in AI, merging two once-distinct paradigms to tackle increasingly complex decision-making problems. The historical roots of this synthesis trace back to the limitations of traditional RL methods, which relied on manually engineered features or tabular representations to approximate value functions and policies. While effective in simpler, low-dimensional tasks, these approaches struggled to scale to environments rich with high-dimensional data, such as raw images, audio signals, or text.

Deep learning offered a solution by automating feature extraction and learning directly from unstructured data. Inspired by the brain's structure and functionality, deep neural networks excelled in capturing intricate patterns and representations, enabling RL agents to perceive and act within environments that were once beyond their reach. The breakthrough moment came with the advent of Deep Q-Networks (DQN) by DeepMind in 2013, which demonstrated that deep neural networks could approximate value functions effectively, allowing agents to play Atari games directly from raw pixel inputs. This achievement marked a paradigm shift, showcasing the potential of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to solve tasks where explicit modeling or feature engineering was impractical.

Motivationally, the integration of deep learning into RL was driven by the desire to create more generalizable and scalable agents. Traditional AI systems often relied on narrow, domain-specific rules that limited their applicability. Researchers aimed to bridge this gap by developing agents capable of learning directly from experience in diverse environments, adapting autonomously to new challenges. This aspiration aligned with broader goals in AI to emulate human-like intelligence, where learning and decision-making are inherently flexible and scalable across various domains.

Moreover, the rise of computational power and access to large-scale datasets in the early 2010s provided fertile ground for this integration. GPUs enabled the efficient training of deep neural networks, while advancements in optimization techniques and frameworks lowered the barriers to implementation. These technological developments, combined with the growing ambition to tackle real-world challenges like robotics, autonomous vehicles, and resource management, fueled the motivation to embed deep learning within RL.

Today, DRL stands as a cornerstone in AI, pushing the boundaries of what machines can achieve. By equipping RL agents with the ability to learn from complex, high-dimensional inputs, deep learning has unlocked the potential for breakthroughs across industries, transforming abstract academic concepts into tangible, impactful solutions.

A deep neural network can be mathematically represented as a composition of functions, each corresponding to a layer in the network:

$$ f_\theta(x) = f_L \circ f_{L-1} \circ \cdots \circ f_1(x), $$

where $f_i(x)$ represents the transformation applied at the $i$-th layer, parameterized by weights $W_i$ and biases $b_i$. Each layer performs a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation function:

$$ f_i(x) = \sigma(W_i x + b_i), $$

with $\sigma$ being an activation function such as ReLU, Sigmoid, or Tanh. These non-linear activations are essential as they allow the network to model complex, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs. The universal approximation theorem assures us that neural networks can approximate any continuous function to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, given sufficient depth and appropriate activation functions.

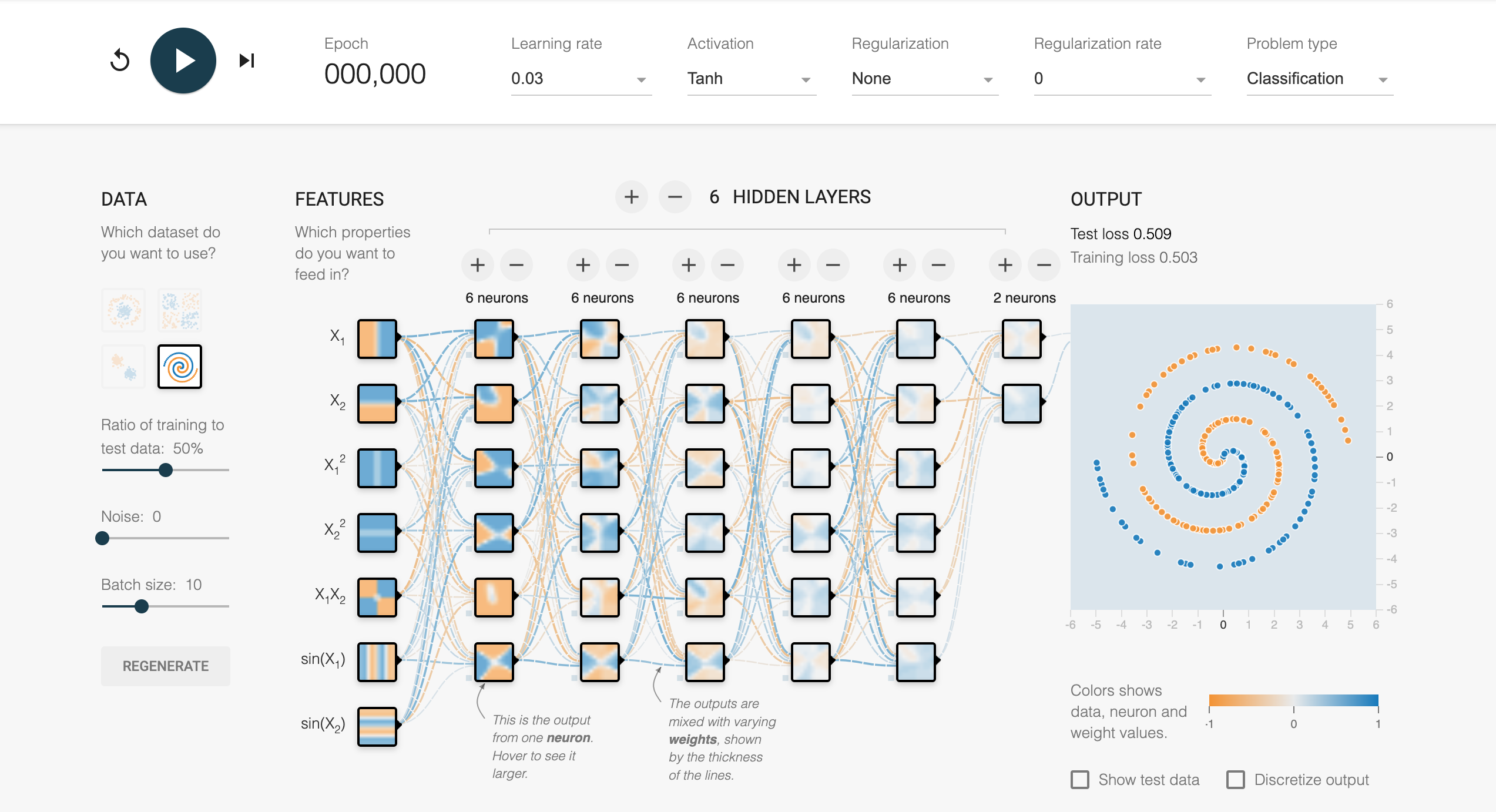

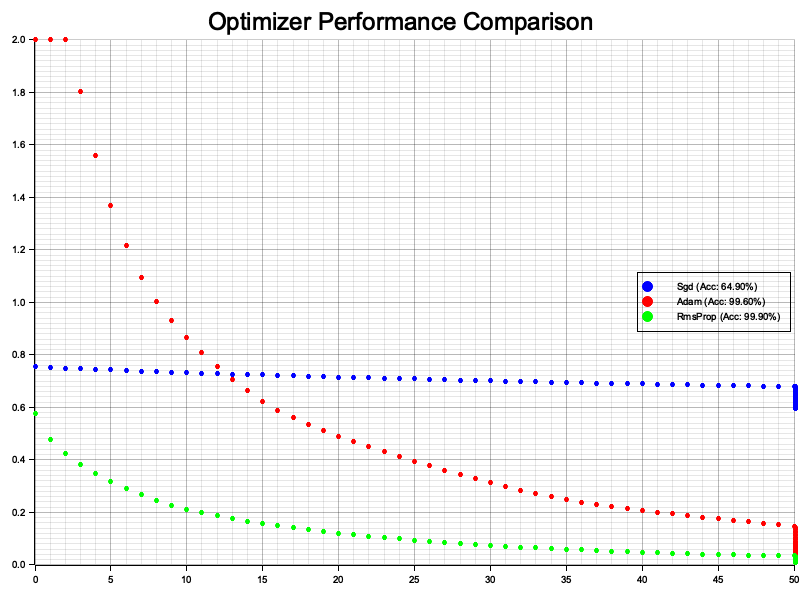

The Tensorflow playground illustrates the core structure and functioning of a basic deep neural network as it processes a classification problem. Each hidden layer in the network corresponds to a transformation $f_i(x) = \sigma(W_i x + b_i)$, where the weights $W_i$ and biases $b_i$ are adjusted during training to minimize the loss function. The use of an activation function, such as the Tanh shown in the image, introduces non-linearity into the transformations, enabling the network to model complex patterns, like the spirals in the dataset. This step-by-step transformation of inputs $x_1$ and $x_2$ through successive hidden layers showcases how the network builds hierarchical representations, from raw input features to a refined understanding of the underlying data distribution.

The visualization from playground also highlights the critical role of network depth in capturing intricate relationships. With six hidden layers, the network gains sufficient capacity to approximate the non-linear decision boundary that separates the two classes in the spiral dataset, as predicted by the universal approximation theorem. The weights connecting the neurons are depicted with varying thickness, representing their magnitude and contribution to the output, while the color coding reflects the activation values. This clear depiction of feature transformations through hidden layers effectively demonstrates how deep learning leverages composition to extract meaningful patterns from raw data.

Figure 1: Illustration of deep learning from Tensorflow Playground (Ref: https://playground.tensorflow.org).

Training these networks involves optimizing the parameters $\theta = \{W_i, b_i\}$ to minimize a loss function $L(\theta)$, which quantifies the discrepancy between the network's predictions and the actual targets. The optimization process leverages the backpropagation algorithm, which efficiently computes the gradients of the loss function with respect to each parameter using the chain rule:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta_i} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial f_i} \cdot \frac{\partial f_i}{\partial \theta_i}. $$

These gradients are then used to update the parameters in the direction that minimizes the loss, typically using gradient descent or one of its variants:

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha \nabla_\theta L, $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, and $\nabla_\theta L$ denotes the gradient of the loss with respect to the parameters. This iterative process allows for the effective training of networks with millions or even billions of parameters.

In the realm of reinforcement learning, deep learning techniques are instrumental in approximating complex functions that are infeasible to model directly. Specifically, neural networks are employed to approximate policies and value functions, which are central to RL algorithms.

Policy-Based Methods: Neural networks parameterize the policy $\pi(a|s)$, mapping states $s$ to a probability distribution over actions $a$. This enables agents to learn stochastic policies that can handle the exploration-exploitation trade-off inherent in RL.

Value-Based Methods: Neural networks estimate the value function $V(s)$ or the action-value function $Q(s, a)$, representing the expected cumulative reward from a state or state-action pair. For instance, Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) use convolutional neural networks to approximate $Q(s, a)$ in environments with visual inputs, like Atari games, allowing agents to learn directly from raw pixel data.

Actor-Critic Methods: These combine policy-based and value-based approaches by simultaneously learning a policy (actor) and a value function (critic), often sharing parameters within a single network architecture.

The integration of deep learning into RL addresses the limitations of traditional machine learning methods, which often rely on manual feature engineering and struggle with high-dimensional or unstructured data. Deep neural networks automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw inputs, enabling RL agents to process complex sensory data without explicit feature extraction. This capability is particularly beneficial in environments where the state space is vast or continuous.

The depth of a neural network is crucial for its ability to capture intricate patterns and dependencies in data. Deeper networks can represent more complex functions by composing multiple layers of non-linear transformations. This hierarchical feature extraction allows lower layers to detect simple patterns, such as edges in images, while higher layers capture more abstract concepts, like objects or even actions.

However, training deep networks comes with challenges, such as vanishing or exploding gradients, which can hinder the optimization process. Techniques like normalization layers, residual connections, and advanced optimization algorithms have been developed to mitigate these issues, facilitating the training of very deep networks.

Deep learning has revolutionized reinforcement learning (RL) by addressing challenges in advanced applications, starting with partial observability. In many real-world environments, agents cannot perceive the complete state of the environment at every step. Here, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks come into play, maintaining a hidden state that summarizes information over time. This capability enables agents to infer crucial details about the environment’s dynamics from past observations, allowing them to make informed decisions even with limited or noisy input. For instance, an LSTM-based RL agent in a partially observable robotics task can remember prior sensor readings to navigate effectively in unseen terrains, exemplifying how deep learning extends RL's capabilities in complex scenarios.

In environments with continuous action spaces, where discrete actions like "move left" or "move right" are insufficient, deep learning offers powerful tools. Methods like Deep Deterministic Policy Gradients (DDPG) and other actor-critic algorithms utilize neural networks to generate smooth, continuous action outputs directly. These approaches allow RL agents to perform fine-grained control in tasks like robotic manipulation or autonomous driving. Additionally, deep learning enhances RL in multi-agent systems, where multiple agents interact in shared environments, often with conflicting goals. Neural networks approximate the policies and value functions for each agent, efficiently managing the combinatorial explosion of possible interactions. Finally, deep learning drives innovations in transfer learning and meta-learning within RL, enabling agents to generalize across tasks by leveraging shared representations. By learning to learn, agents can adapt quickly to new challenges, reducing training time and enhancing performance in diverse applications, from gaming to real-world decision-making.

Nowadays, deep learning has become an indispensable component of modern reinforcement learning, providing the computational machinery necessary to handle the complexities of real-world environments. By leveraging the hierarchical learning capabilities of deep neural networks, RL agents can learn effective policies and value functions directly from raw, high-dimensional data. This synergy between deep learning and reinforcement learning continues to drive advancements in artificial intelligence, enabling the development of agents capable of sophisticated decision-making and problem-solving in diverse domains.

Practically, implementing deep learning in Rust for RL applications involves structuring neural networks as modular and efficient systems. Rust's type safety, performance, and memory management make it a powerful choice for building RL agents. AI engineers can define layers as structs, encapsulating weights, biases, and activation functions as properties, and implement forward passes as methods. Libraries like ndarray and tch-rs provide robust support for matrix operations and tensor computations, enabling seamless integration of linear transformations and activation functions. By leveraging Rust's features, RL practitioners can create scalable, high-performance neural networks that handle the complexities of modern reinforcement learning environments effectively. This integration of foundational concepts with Rust’s practical capabilities ensures the development of RL systems that are both robust and efficient.

This Rust program implements a simple feedforward neural network using the tch library for training a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to classify synthetic 2D circular data points into two categories. The program generates a dataset with circular patterns, builds an MLP with six layers (five hidden layers and one output layer), trains it using the Adam optimizer, and visualizes the decision boundary and classified points. Gradients and predictions during forward and backward propagation are logged to demonstrate the learning process.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::ModuleT;

fn main() -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// 1. Generate 2D synthetic datasets with circular pattern

let n_samples = 1000;

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut data = Vec::new();

let mut labels = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..n_samples {

let r = rng.gen_range(0.0..2.0);

let theta = rng.gen_range(0.0..(2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI));

let x = r * theta.cos();

let y = r * theta.sin();

data.push([x, y]);

labels.push(if r < 1.0 { 0 } else { 1 });

}

let data: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let labels: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&labels)

.to_kind(Kind::Int64)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

// 2. Define Multi-Layer Perceptron with 6 hidden layers (8 neurons each)

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 2, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 8, 2, Default::default()));

// 3. Train the model using Adam optimizer

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

for epoch in 1..=500 {

// Forward pass

let preds = net.forward_t(&data, true);

// Log forward pass output for the first batch

if epoch == 1 || epoch % 100 == 0 {

println!("Epoch {} - Forward pass output (first 5 samples): {:?}", epoch, preds.narrow(0, 0, 5));

}

// Compute loss

let loss = preds.cross_entropy_for_logits(&labels);

// Backward pass

opt.zero_grad();

loss.backward();

// Optimizer step

opt.step();

if epoch % 50 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:.4}", epoch, loss.double_value(&[]));

}

}

// 4. Evaluate and visualize the results

let preds = net.forward_t(&data, false).argmax(1, false);

let accuracy = preds.eq_tensor(&labels).to_kind(Kind::Float).mean(Kind::Float);

println!("Accuracy: {:.2}%", accuracy.double_value(&[]) * 100.0);

// Visualization setup

let root = BitMapBackend::new("classification_visualization.png", (800, 800)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.margin(5)

.caption("MLP Classification and Predictions", ("sans-serif", 30))

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(-2.5..2.5, -2.5..2.5)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

// Plot decision boundary

let resolution = 200;

let mut grid_data = vec![];

for i in 0..resolution {

for j in 0..resolution {

let x = -2.5 + 5.0 * (i as f64) / (resolution as f64);

let y = -2.5 + 5.0 * (j as f64) / (resolution as f64);

grid_data.push([x, y]);

}

}

let grid_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&grid_data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let grid_preds = net.forward_t(&grid_tensor, false).argmax(1, false);

let grid_points: Vec<(f64, f64, u8)> = grid_data

.iter()

.zip(grid_preds.iter::<i64>().unwrap())

.map(|(coords, label)| (coords[0], coords[1], label as u8))

.collect();

chart.draw_series(

grid_points.iter().map(|(x, y, label)| {

let color = if *label == 0 { &BLUE.mix(0.2) } else { &RED.mix(0.2) };

Circle::new((*x, *y), 1, color.filled())

}),

)?;

// Plot original data points

let data_points: Vec<((f64, f64), i64)> = data

.to_kind(Kind::Double)

.chunk(2, 1)

.iter()

.zip(labels.iter::<i64>().unwrap())

.map(|(coords, label)| {

let x = coords.double_value(&[0]);

let y = coords.double_value(&[1]);

((x, y), label)

})

.collect();

chart.draw_series(

data_points

.iter()

.filter(|(_, label)| *label == 0)

.map(|((x, y), _)| Circle::new((*x, *y), 3, BLUE.filled())),

)?;

chart.draw_series(

data_points

.iter()

.filter(|(_, label)| *label == 1)

.map(|((x, y), _)| Circle::new((*x, *y), 3, RED.filled())),

)?;

root.present()?;

println!("Visualization saved to classification_visualization.png");

Ok(())

}

The program begins by generating a synthetic dataset with 2D points arranged in concentric circles, assigning labels based on the radius. It then constructs an MLP with ReLU activation for hidden layers and a linear transformation for the output layer. During training, the network performs forward propagation to compute predictions, calculates the cross-entropy loss, and applies backward propagation to update the model’s weights using gradients. Logging mechanisms provide insights into the forward outputs, loss values, and gradient updates for specific layers. After training, the network's decision boundary and predictions are visualized to evaluate performance.

Forward propagation involves passing input data through the neural network to compute output predictions. Each layer applies a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation (e.g., ReLU), propagating information from input to output. Backward propagation, or backprop, calculates gradients of the loss function with respect to model parameters using the chain rule. These gradients indicate how each parameter contributes to the error, enabling the optimizer (Adam in this case) to adjust weights and biases in the direction that minimizes the loss. Together, forward and backward propagation iteratively refine the model's parameters to improve performance on the classification task.

By running this example, you can observe the network's ability to learn the target value function through gradient-based optimization, illustrating the principles of forward and backward propagation in a deep learning system tailored for reinforcement learning tasks.

15.2. Linear and Nonlinear Transformations

In the realm of reinforcement learning (RL), neural networks serve as versatile tools for approximating complex functions, enabling agents to make decisions in dynamic and high-dimensional environments. These networks fundamentally operate by processing inputs through a series of layers, where each layer applies transformations that extract and refine meaningful features. At their core, neural networks leverage two key operations: linear transformations and nonlinear activation functions. These operations work in tandem, allowing the network to represent intricate relationships and capture the underlying structure of data.

Linear transformations form the backbone of neural networks, where inputs are multiplied by weights and combined with biases. This operation enables the network to compute weighted sums of inputs, effectively projecting data into different spaces. However, linear transformations alone are insufficient for capturing complex, nonlinear patterns in data. This is where nonlinear activation functions become essential. Activation functions, such as ReLU, Sigmoid, and Tanh, introduce nonlinearity to the network, allowing it to model intricate dependencies and decision boundaries. Nonlinearities enable neural networks to approximate complex functions and relationships, making them capable of solving tasks ranging from image recognition to strategic decision-making in RL.

A linear transformation is a fundamental mathematical operation that maps an input vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ to an output vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^m$ using a weight matrix $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$ and a bias vector $\mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{R}^m$:

$$ \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}. $$

In this equation, the matrix $\mathbf{W}$ defines how each input feature contributes to each output feature, while the bias vector $\mathbf{b}$ allows for shifting the transformation, providing the network with additional flexibility. Linear transformations serve as the building blocks of neural networks, forming the connections between layers. In the context of RL, these transformations help map states to actions or value estimates, facilitating the agent's understanding of the environment. For instance, in policy networks, linear layers can map high-dimensional state representations to action probabilities.

Despite their fundamental role, linear transformations have inherent limitations in expressive power. Stacking multiple linear layers without any nonlinearity results in another linear transformation. Mathematically, if we have two linear transformations $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}_2 (\mathbf{W}_1 \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}_1) + \mathbf{b}_2$, this can be simplified to a single linear transformation $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}' \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}$, where $\mathbf{W}' = \mathbf{W}_2 \mathbf{W}_1$ and $\mathbf{b}' = \mathbf{W}_2 \mathbf{b}_1 + \mathbf{b}_2$. This linearity restricts the network's ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships present in RL tasks, such as interactions between different state variables or non-additive reward structures.

To overcome the limitations of linear transformations, neural networks incorporate nonlinear activation functions applied element-wise to the outputs of linear layers. These nonlinearities introduce the necessary complexity, enabling networks to model intricate functions and decision boundaries. The significance of nonlinear activation functions is underscored by the Universal Approximation Theorem (UAT), which states that a feedforward neural network with at least one hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons and a suitable nonlinear activation function can approximate any continuous function on a compact subset of $\mathbb{R}^n$ to any desired degree of accuracy. This theorem provides the theoretical foundation for using neural networks as universal function approximators in RL.

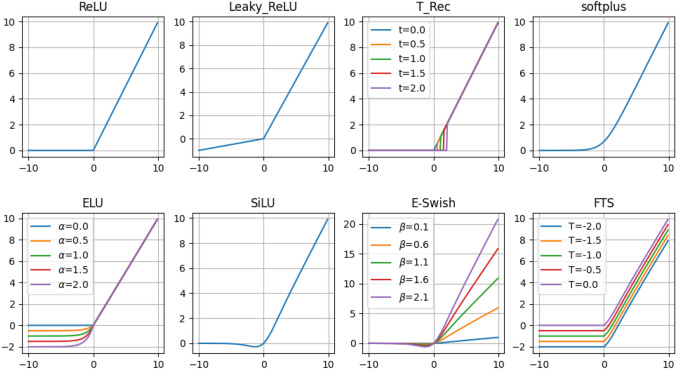

Figure 2: Commonly used activation functions for deep learning.

Among the most common activation functions is the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), defined as:

$$ \text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0, x). $$

ReLU is computationally efficient and mitigates the vanishing gradient problem by providing a constant gradient for positive inputs. It is widely used in deep RL architectures due to its simplicity and effectiveness, particularly in convolutional neural networks processing visual inputs.

Another fundamental activation function is the sigmoid function $\sigma(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}}$, which outputs values in the range (0, 1), making it suitable for modeling probabilities. However, it is prone to vanishing gradients for large positive or negative inputs, which can slow down learning. In RL, the sigmoid function is commonly used in the output layer when modeling binary actions or probabilities.

The hyperbolic tangent function (tanh) is also widely used, defined as:

$$ \tanh(x) = \frac{e^{x} - e^{-x}}{e^{x} + e^{-x}}. $$

Tanh centers data around zero and outputs values in the range (-1, 1), which can be beneficial in hidden layers where centered data improves convergence. However, like the sigmoid function, tanh can suffer from vanishing gradients, especially for inputs far from zero.

Modern deep learning introduces advanced activation functions to address the shortcomings of traditional functions, particularly in the context of deep RL. The Leaky ReLU is one such function, defined as:

$$ \text{LeakyReLU}(x) = \begin{cases} x, & \text{if } x > 0, \\ \alpha x, & \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} $$

where $\alpha$ is a small constant, typically 0.01. Leaky ReLU allows a small, non-zero gradient when the unit is not active (i.e., $x < 0$), preventing "dead" neurons and enhancing the learning capacity in networks where negative inputs are significant.

The Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) is another advanced activation function, given by:

$$ \text{ELU}(x) = \begin{cases} x, & \text{if } x \geq 0, \\ \alpha (e^{x} - 1), & \text{if } x < 0, \end{cases} $$

where $\alpha$ is a positive constant. ELU improves learning by bringing mean activations closer to zero and reduces computational complexity. In RL, it is beneficial in deep networks where faster convergence is desired.

The Swish function is defined as:

$$ \text{Swish}(x) = x \cdot \sigma(x), $$

and has been shown to outperform ReLU in deep networks by providing better gradient flow. It enhances performance in policy and value networks by allowing smoother transitions between activated and non-activated states.

The Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) is another activation function, defined as:

$$ \text{GELU}(x) = x \cdot \Phi(x), $$

where $\Phi(x)$ is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. GELU applies a smooth gating mechanism, enabling networks to capture complex patterns. It is particularly useful in transformer architectures and advanced RL models requiring sophisticated function approximation.

The Universal Approximation Theorem (UAT) s a foundational result in neural network theory that demonstrates the expressive power of feedforward neural networks. Formally, it states that a feedforward network with at least one hidden layer, a finite number of neurons, and a suitable nonlinear activation function can approximate any continuous function $f$ defined on a compact subset $K \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$ to any desired degree of accuracy. This result highlights the theoretical capability of neural networks to serve as universal function approximators.

Mathematically, the theorem asserts that for any continuous function $f: K \to \mathbb{R}$ and any $\varepsilon > 0$, there exists a neural network $\phi(x)$ such that:

$$ \sup_{x \in K} \left| f(x) - \phi(x) \right| < \varepsilon,x∈K $$

where $\phi(x)$ is the output of the neural network. The network represents $\phi(x)$ as a sum of weighted activation functions applied to linear combinations of inputs:

$$ \phi(x) = \sum_{i=1}^M c_i \, \sigma \left( w_i^T x + b_i \right). $$

Here, $M$ is the number of neurons in the hidden layer, $c_i \in \mathbb{R}$ are the output weights, $w_i \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and $b_i \in \mathbb{R}$ are the input weights and biases, and $\sigma: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is the nonlinear activation function. The choice of activation function $\sigma$ is critical; it must be nonlinear (e.g., sigmoid, hyperbolic tangent, or ReLU) to ensure the network's ability to approximate complex functions.

The theorem guarantees that such a neural network can approximate $f(x)$ on $K$ with finite neurons, but it does not provide explicit bounds on the number of neurons or layers required to achieve a specific accuracy $\varepsilon$. Additionally, the approximation is valid only for continuous functions over compact subsets, meaning extensions are needed for discontinuous functions or non-compact domains.

The UAT is particularly significant in the context of reinforcement learning (RL), where agents learn to make sequences of decisions to maximize cumulative rewards. RL environments often feature stochastic and nonlinear dynamics, with complex state-action-reward relationships. Neural networks with nonlinear activation functions are crucial for modeling these complexities effectively, enabling agents to approximate value functions and policies that drive optimal decision-making.

Nonlinearity is indispensable for capturing intricate dependencies in RL. For example, optimal policies and value functions in RL are rarely linear in the state space; they often require the representation of sharp changes or steep gradients in response to critical state transitions. Nonlinear activation functions allow neural networks to approximate these relationships, ensuring that the expected return can be estimated accurately. Without nonlinearity, linear models would fail to capture the richness of interactions between states and actions, leading to suboptimal policies.

In high-dimensional and continuous spaces, nonlinearities become even more critical. For RL problems involving visual inputs, such as those requiring image-based state representations, deep convolutional networks with nonlinear activation functions are essential. These networks learn hierarchical representations, progressing from low-level features like edges and textures in early layers to high-level abstractions like objects or scenes in deeper layers. Similarly, in continuous action spaces, nonlinear transformations enable the modeling of nuanced action-reward effects, allowing agents to learn precise control policies.

Linear models are fundamentally insufficient for most RL tasks, particularly in environments where rewards depend on nonlinear interactions between state variables. For instance, environments with rewards that exhibit sharp transitions or non-smooth behavior require approximations that can capture these features. Nonlinear activation functions empower neural networks to approximate such complex mappings, handling steep gradients, and interactions among state variables.

The choice of activation functions significantly impacts the performance and convergence of RL algorithms. Functions like ReLU and its variants enhance training stability by mitigating vanishing gradient problems, which is vital for stable and efficient learning. Moreover, advanced activation functions such as Swish and GELU provide smoother gradients, facilitating better gradient flow in very deep networks and improving convergence. These properties are especially important in RL, where agents often need to balance exploration and exploitation over long training horizons.

Computational efficiency is another key factor in RL applications. Simpler activation functions, like ReLU, are computationally efficient and suitable for real-time or resource-constrained scenarios. In contrast, smoother functions like Swish may offer better convergence properties in deep networks, albeit at a slight computational cost. Balancing computational overhead with expressive power is crucial, particularly in RL applications where agents must operate in real-time or handle complex, high-dimensional environments.

In summary, the UAT provides the theoretical justification for using neural networks in RL, but practical considerations—such as network architecture, activation function choice, and computational constraints—play a significant role in real-world performance. By leveraging nonlinear activation functions effectively, RL agents can approximate complex policies and value functions, enabling them to navigate and succeed in dynamic, high-dimensional environments.

Practical considerations in RL include the combination of batch normalization with certain activation functions to further improve training dynamics. Batch normalization helps in stabilizing the distribution of inputs to each layer, which can mitigate issues like internal covariate shift and improve training speed. Activation functions that affect the distribution of outputs can influence the agent's exploration strategies, impacting the balance between exploration and exploitation, a fundamental trade-off in RL.

In some RL scenarios, designing custom activation functions tailored to the problem domain can yield better performance. For instance, in domains where the agent's actions must satisfy certain constraints or where the reward landscape has specific characteristics, specialized activation functions can help the network learn more effectively.

Implementing linear and nonlinear transformations in Rust involves leveraging the language's features to achieve efficient computation. Rust's low-level control allows for optimization of matrix operations and activation function computations, which are critical in high-performance RL applications. Utilizing Rust's concurrency features can parallelize computations across CPU cores or GPU threads, enhancing performance for large-scale problems.

Safety is ensured through Rust's ownership system, preventing data races and ensuring memory safety in multi-threaded RL applications. This is particularly important in RL, where agents often need to interact with environments and process data streams concurrently.

By harnessing the power of Rust for implementing these concepts, practitioners can build robust, high-performance RL systems capable of tackling real-world challenges. Rust's strong type system and emphasis on safety without sacrificing performance make it an excellent choice for developing RL frameworks and algorithms.

Linear and nonlinear transformations are integral to the success of deep learning in reinforcement learning. Linear transformations provide the structural framework for neural networks, mapping inputs through layers of computation. Nonlinear activation functions imbue these networks with the capacity to model the complex, dynamic environments encountered in RL. Understanding the mathematical foundations and practical implications of these transformations is essential for developing efficient and effective RL agents.

As RL continues to evolve, the interplay between linear structures and nonlinear activations will remain a cornerstone of agent development and innovation. By combining these mathematical tools with the performance and safety of Rust, practitioners can push the boundaries of what RL agents can achieve, enabling them to solve increasingly sophisticated tasks across diverse domains.

To illustrate these concepts, we implement linear transformations and activation functions in Rust using the tch crate. We also visualize decision boundaries created by different activation functions to understand their behavior. The experiment in the code explores the performance and decision boundary visualization of a neural network with different activation functions: ReLU, Leaky ReLU, and ELU. The model is trained to classify a synthetic dataset with two concentric circular patterns into two categories. Each activation function affects the learning dynamics and the shape of the decision boundary, influencing the classification performance.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::ModuleT;

// Custom sequential network with configurable activation function

fn create_network(vs: &nn::VarStore, activation: &str) -> nn::Sequential {

let root = vs.root();

match activation {

"relu" => nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&root, 2, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 2, Default::default())),

"leaky_relu" => nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&root, 2, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.leaky_relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.leaky_relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.leaky_relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 2, Default::default())),

"elu" => nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&root, 2, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.elu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.elu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.elu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 2, Default::default())),

_ => panic!("Unsupported activation function"),

}

}

// Function to generate circular dataset

fn generate_dataset(n_samples: usize) -> (Vec<[f64; 2]>, Vec<i64>) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut data = Vec::new();

let mut labels = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..n_samples {

let r = rng.gen_range(0.0..2.0);

let theta = rng.gen_range(0.0..(2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI));

let x = r * theta.cos();

let y = r * theta.sin();

data.push([x, y]);

labels.push(if r < 1.0 { 0 } else { 1 });

}

(data, labels)

}

// Function to train and evaluate network

fn train_network(

net: &nn::Sequential,

data: &Tensor,

labels: &Tensor,

opt: &mut nn::Optimizer,

epochs: usize,

) -> f64 {

for epoch in 1..=epochs {

// Forward pass

let preds = net.forward_t(data, true);

// Compute loss

let loss = preds.cross_entropy_for_logits(labels);

// Backward pass and optimization

opt.backward_step(&loss);

// Print loss every 50 epochs

if epoch % 50 == 0 {

println!("Epoch {}: Loss: {:.4}", epoch, loss.double_value(&[]));

}

}

// Compute accuracy

let preds = net.forward_t(data, false).argmax(1, false);

let accuracy = preds.eq_tensor(labels).to_kind(Kind::Float).mean(Kind::Float);

accuracy.double_value(&[]) * 100.0

}

// Function to visualize decision boundaries

fn visualize_decision_boundary(

net: &nn::Sequential,

activation: &str,

accuracy: f64,

) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Fix: Create a variable for the filename

let filename = format!("{}_classification.png", activation);

let root = BitMapBackend::new(&filename, (800, 800)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.margin(5)

.caption(

format!("{} Activation (Accuracy: {:.2}%)", activation.to_uppercase(), accuracy),

("sans-serif", 30),

)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(-2.5..2.5, -2.5..2.5)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

// Plot decision boundary

let resolution = 200;

let mut grid_data = vec![];

for i in 0..resolution {

for j in 0..resolution {

let x = -2.5 + 5.0 * (i as f64) / (resolution as f64);

let y = -2.5 + 5.0 * (j as f64) / (resolution as f64);

grid_data.push([x, y]);

}

}

let grid_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&grid_data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let grid_preds = net.forward_t(&grid_tensor, false).argmax(1, false);

let grid_points: Vec<(f64, f64, u8)> = grid_data

.iter()

.zip(grid_preds.iter::<i64>().unwrap())

.map(|(coords, label)| (coords[0], coords[1], label as u8))

.collect();

// Draw decision boundary

chart.draw_series(

grid_points.iter().map(|(x, y, label)| {

let color = if *label == 0 { &BLUE.mix(0.2) } else { &RED.mix(0.2) };

Circle::new((*x, *y), 1, color.filled())

}),

)?;

// Draw original data points

let (data, labels) = generate_dataset(1000);

let data_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let labels_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&labels)

.to_kind(Kind::Int64)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let data_points: Vec<((f64, f64), i64)> = data_tensor

.to_kind(Kind::Double)

.chunk(2, 1)

.iter()

.zip(labels_tensor.iter::<i64>().unwrap())

.map(|(coords, label)| {

let x = coords.double_value(&[0]);

let y = coords.double_value(&[1]);

((x, y), label)

})

.collect();

chart.draw_series(

data_points

.iter()

.filter(|(_, label)| *label == 0)

.map(|((x, y), _)| Circle::new((*x, *y), 3, BLUE.filled())),

)?;

chart.draw_series(

data_points

.iter()

.filter(|(_, label)| *label == 1)

.map(|((x, y), _)| Circle::new((*x, *y), 3, RED.filled())),

)?;

root.present()?;

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Set random seed for reproducibility

tch::maybe_init_cuda();

// Activation functions to compare

let activations = ["relu", "leaky_relu", "elu"];

// Generate dataset

let (data, labels) = generate_dataset(1000);

let data_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let labels_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&labels)

.to_kind(Kind::Int64)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

// Compare different activation functions

for activation in &activations {

println!("\nTraining with {} activation", activation);

// Create VarStore and network

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let net = create_network(&vs, activation);

// Create optimizer

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3)?;

// Train network

let accuracy = train_network(&net, &data_tensor, &labels_tensor, &mut opt, 500);

// Visualize decision boundary

visualize_decision_boundary(&net, activation, accuracy)?;

println!("Accuracy with {}: {:.2}%", activation, accuracy);

}

println!("\nDecision boundary visualizations saved!");

Ok(())

}

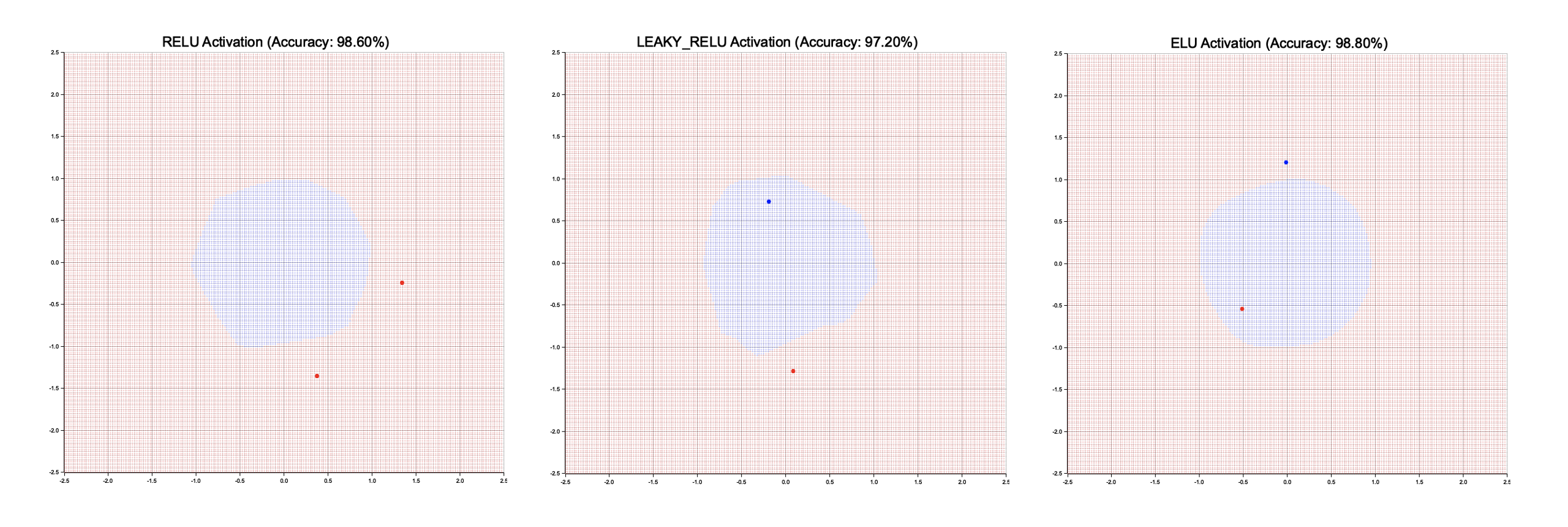

The program generates a 2D dataset of points within a circular region, assigning labels based on the distance from the origin. A multi-layer perceptron (MLP) is constructed with four layers, each with eight neurons, using one of the three activation functions. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer for 500 epochs, and the resulting decision boundary is visualized for each activation function. The visualizations are saved as separate charts, each showing the model's accuracy and classification boundary.

Figure 3: Plotters visualization decision boundaries of different activation functions.

The visualizations show that all three activation functions effectively classify the data, achieving high accuracy (97-99%). However, the shape and smoothness of the decision boundary vary slightly due to the different properties of the activation functions. ReLU generally produces sharp boundaries, while Leaky ReLU offers slight flexibility in negative regions, and ELU results in smoother transitions near the boundary. These differences highlight how activation functions influence the learned representation and decision-making of neural networks.

By implementing and experimenting with these transformations, readers gain insight into the critical role of non-linearity in enabling neural networks to solve reinforcement learning tasks effectively. Through practical exploration, the importance of activation functions in defining decision boundaries and optimizing network performance becomes evident.

15.3. Optimization Techniques

Optimization is the cornerstone of training neural networks in reinforcement learning (RL), enabling agents to refine their decision-making capabilities and adapt to dynamic environments. At its essence, optimization is the iterative process through which an agent improves its neural network's parameters—its weights and biases—to better approximate policies or value functions. The goal is to minimize a loss function, which measures the discrepancy between the agent's predictions and the desired outcomes, ultimately guiding the agent toward optimal behavior.

The training process relies on gradient-based optimization methods, where gradients indicate the direction and magnitude of change required to improve the loss function. Advanced algorithms like Adam and RMSProp have become indispensable in deep RL due to their ability to adapt learning rates dynamically for each parameter. Adam, for instance, combines the advantages of momentum and adaptive learning rates, allowing for efficient convergence even in high-dimensional parameter spaces. RMSProp, on the other hand, excels in handling non-stationary objectives, which are common in RL environments where the agent's learning dynamics are constantly evolving. These optimizers provide stability and efficiency in navigating the complex, rugged landscapes of RL loss functions.

However, optimization in deep RL presents unique challenges. Unlike supervised learning, where data is independently and identically distributed, RL involves learning from sequential, correlated data generated by the agent's interactions with the environment. This introduces issues such as high variance in gradient estimates and the instability of training due to feedback loops between the agent's policy and its experience. Techniques like experience replay, which stores past interactions for sampling, and target networks, which stabilize updates, address these challenges by breaking data correlations and smoothing learning dynamics.

The cornerstone of optimization in deep learning is gradient descent, an iterative method used to minimize a loss function $L(\theta)$ with respect to the network parameters $\theta$. At each time step ttt, the parameters are updated in the opposite direction of the gradient of the loss function:

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha \nabla_\theta L, $$

where $\alpha > 0$ is the learning rate, controlling the step size of each update, and $\nabla_\theta L$ is the gradient of the loss function with respect to $\theta$. The gradient provides the direction of the steepest ascent, so moving in the negative gradient direction leads to the steepest descent, ideally reducing the loss.

In the context of RL, calculating the full gradient over the entire dataset (full-batch gradient descent) is often impractical due to the sequential and interactive nature of data generation. Instead, stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is employed, which updates parameters using gradients computed from small, randomly sampled batches of data:

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha \nabla_\theta L(\theta_t; \mathcal{B}_t), $$

where $\mathcal{B}_t$ is a mini-batch sampled from the data at time $t$. While SGD introduces noise into the gradient estimates, it allows for more frequent updates and can help escape local minima. However, vanilla SGD has limitations, such as sensitivity to the choice of learning rate and difficulty in navigating the noisy, non-convex loss landscapes typical in deep RL.

To overcome these challenges, advanced optimization algorithms incorporate concepts like momentum and adaptive learning rates, which are particularly beneficial in RL settings where rewards can be sparse or noisy.

Figure 4: Animation of ADAM (Blue), RMSProp (Green) and AdaGrad(White) compared to SGD (White).

The Adam optimizer is a powerful optimization algorithm that combines the benefits of adaptive learning rates and momentum-based optimization, making it highly effective for training deep neural networks. Unlike standard stochastic gradient descent (SGD), Adam adapts the learning rate for each parameter individually by maintaining running averages of both the first and second moments of the gradients. This adaptive approach allows for efficient convergence even in the presence of noisy gradients or sparse features.

The parameter update rule in Adam is given by:

$$ \theta_t = \theta_{t-1} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon} \hat{m}_t, $$

where:

$\theta_t$ is the parameter value at iteration ttt,

$\eta$ is the learning rate, controlling the step size,

$\hat{m}_t$ is the bias-corrected estimate of the first moment (mean) of the gradients,

$\hat{v}_t$ is the bias-corrected estimate of the second moment (uncentered variance) of the gradients,

$\epsilon$ is a small constant (e.g., $10^{-8}$) added to prevent division by zero.

The first moment estimate, $m_t$, captures the exponentially decayed average of past gradients, introducing momentum to stabilize updates and accelerate convergence in relevant directions. Simultaneously, the second moment estimate, $v_t$, tracks the exponentially decayed average of the squared gradients, allowing the algorithm to scale updates based on the magnitude of the gradients. Both moments are corrected for bias during the early iterations using their respective bias-corrected forms $\hat{m}_t$ and $\hat{v}_t$.

By combining these mechanisms, Adam provides robust and adaptive parameter updates, enabling faster and more stable convergence across a wide range of optimization problems. Its ability to dynamically adjust learning rates for each parameter makes it particularly well-suited for high-dimensional and complex optimization landscapes, such as those encountered in deep learning tasks.

Adam adapts the learning rate for each parameter individually, scaling it inversely proportional to the square root of the estimated variance, which helps in dealing with sparse gradients and noisy loss functions common in RL.

RMSProp is another optimizer designed to handle non-stationary objectives, which are prevalent in RL due to the changing policies and value estimates. RMSProp adjusts the learning rate based on a moving average of squared gradients:

$$ v_t = \beta v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta) g_t^2, $$

$$ \theta_t = \theta_{t-1} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{v_t} + \epsilon} g_t, $$

where $\beta$ is typically set to 0.9. By dividing the learning rate by the root mean square (RMS) of recent gradients, RMSProp normalizes the parameter updates, preventing them from becoming too large and ensuring more stable convergence.

AdaGrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter based on the accumulated squared gradients from the beginning of training:

$$ G_t = G_{t-1} + g_t^2, $$

$$ \theta_t = \theta_{t-1} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{G_t} + \epsilon} g_t, $$

where $G_t$ is a diagonal matrix containing the sum of the squares of the gradients with respect to each parameter up to time ttt. AdaGrad is effective for problems with sparse rewards, as it increases the learning rate for infrequently updated parameters, allowing the optimizer to make larger updates when necessary.

Optimization in deep RL presents unique challenges that distinguish it from supervised learning. These challenges stem from the interactive nature of RL, the temporal dependency of data, and the inherent instability in training agents that learn from their own experience.

In RL, the data distribution is non-stationary because the agent's policy, which determines the data it collects, evolves during training. This non-stationarity can lead to unstable gradients, causing oscillations or divergence in the training process. The sequential dependency of states and actions exacerbates this issue, as small changes in the policy can significantly alter future states and rewards.

Many RL environments provide infrequent or delayed rewards, resulting in sparse and noisy gradient estimates. When rewards are sparse, the agent receives less feedback about the effectiveness of its actions, making it difficult to compute reliable gradients for updating the network parameters. This sparsity can slow down learning and requires the optimizer to handle high variance in the gradient estimates.

The temporal credit assignment problem is a core challenge in RL, where the agent must determine which actions are responsible for future rewards. Since rewards may be delayed by many time steps, the optimizer must accurately backpropagate the reward signal through time to adjust the parameters appropriately. This delay complicates the optimization landscape, as the network must capture long-term dependencies.

To address these challenges, various strategies have been developed to stabilize training and improve convergence in deep RL.

Introduced in deep Q-networks (DQNs), target networks help stabilize the training by providing a consistent set of parameters for computing target values in the temporal difference (TD) error. A target network $\theta^-$ is a delayed copy of the primary network $\theta$, updated less frequently:

$$ \theta^- \leftarrow \theta \quad \text{every} \quad N \quad \text{steps}. $$

By keeping the target network fixed for several updates, the method reduces the moving target problem, where both the estimated values and the target values are changing simultaneously, leading to instability.

Gradient clipping is a technique used to prevent exploding gradients, which can occur in recurrent architectures or when dealing with high variability in RL environments. By clipping the gradients to a predefined threshold, the optimizer ensures that parameter updates remain within reasonable bounds:

$$ g_t = \text{clip}(g_t, -k, k), $$

where $k$ is the clipping threshold. This technique helps maintain stable learning dynamics and prevents the optimizer from making drastic updates that could destabilize training.

Experience replay involves storing past experiences in a memory buffer and sampling mini-batches uniformly or according to some priority for training. This approach breaks the correlations between sequential data and smooths out learning by providing a more stationary data distribution. It allows the optimizer to learn from a more diverse set of experiences, improving gradient estimates and convergence.

Applying normalization methods such as batch normalization or layer normalization can help stabilize training by reducing internal covariate shift. Normalization adjusts the inputs to each layer to have zero mean and unit variance, which can improve the optimizer's effectiveness and speed up training.

Implementing optimization algorithms for reinforcement learning (RL) in Rust demands a meticulous approach to balance performance and flexibility. Rust’s focus on zero-cost abstractions, memory safety, and concurrency makes it an ideal choice for high-performance neural network training. By leveraging libraries such as ndarray for n-dimensional array manipulations or tch-rs for PyTorch interoperability, developers can implement advanced optimizers like Adam and RMSProp. These tools enable efficient tensor operations and parallelized computations, ensuring that RL agents learn robustly in computationally intensive environments. Rust’s capabilities provide a foundation for scalable, reliable, and efficient systems tailored for state-of-the-art RL applications.

Rust’s ownership model and type system inherently ensure memory safety without compromising execution speed, a critical requirement in RL where real-time performance is often necessary. Its low-level control over memory and efficient concurrency primitives facilitates the implementation of tensor operations, gradient computations, and parallel training pipelines. Libraries like ndarray and autograd crates support the development of custom neural network components, enabling practitioners to fine-tune optimization algorithms and adapt them to specific RL tasks.

Concurrency, a cornerstone of RL training, benefits greatly from Rust’s zero-cost abstractions and native support for multi-threading and asynchronous programming. For instance, experience replay buffers and data loaders can operate concurrently with the training loop, significantly speeding up the learning process. Rust’s concurrency model ensures thread safety and minimizes overhead, making it ideal for deploying RL agents in real-world, performance-critical scenarios.

Interoperability is another strength of Rust in the RL domain. By leveraging foreign function interfaces (FFI), Rust can integrate seamlessly with existing deep learning frameworks, enabling access to GPU acceleration and advanced libraries. This allows developers to offload computationally expensive tasks, such as forward passes and backpropagation, to external frameworks while retaining Rust’s safety and performance benefits for other system components.

Optimization techniques are pivotal in RL, especially given the unique challenges of non-stationarity and sparse rewards. Gradient-based methods like Adam and RMSProp offer tailored solutions to these issues, improving convergence and stability in environments with dynamic or delayed feedback. Implementing these methods in Rust amplifies their benefits, as the language’s efficiency and safety features allow for the development of highly reliable and performant RL systems. This synergy between advanced optimization techniques and Rust’s robust ecosystem positions developers to tackle the computational and algorithmic complexities of modern RL tasks.

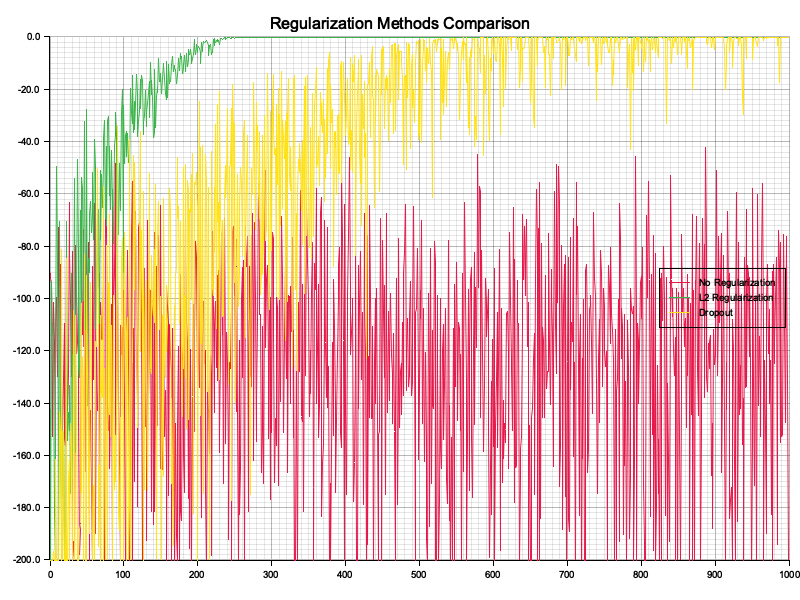

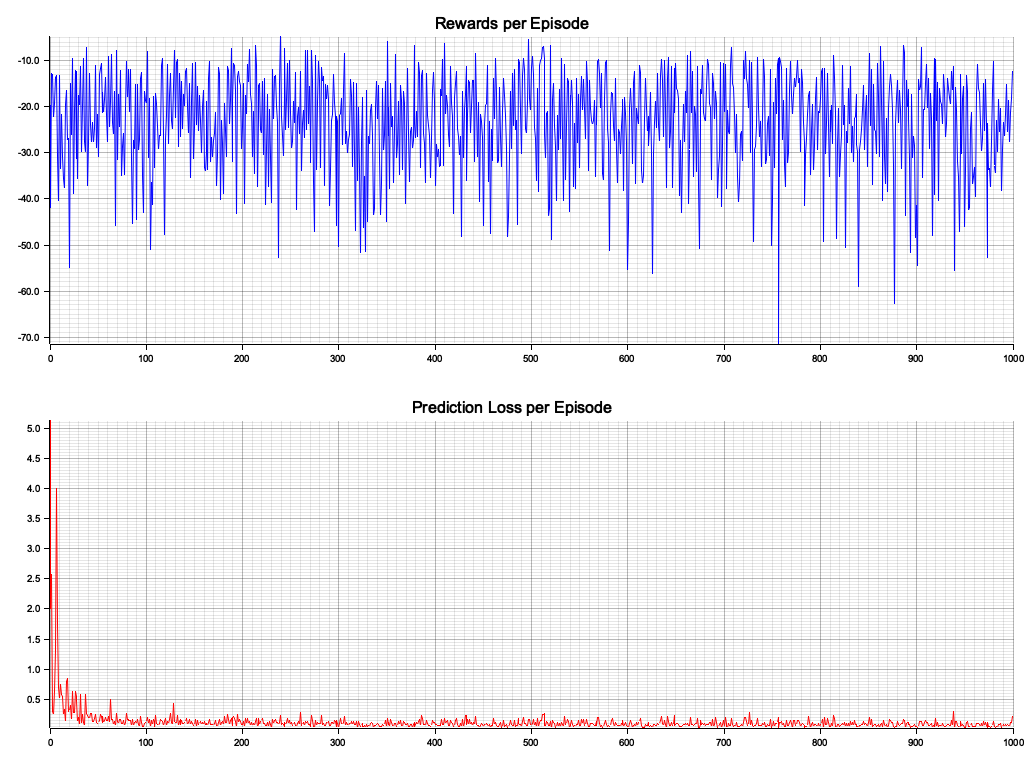

This experiment compares the performance of three popular optimization algorithms—SGD, Adam, and RMSprop—on training a neural network for a binary classification task. The dataset consists of points sampled within concentric circular patterns, and the network's performance is evaluated based on its loss curve and final accuracy. The aim is to understand how different optimizers affect the convergence rate and final model accuracy.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use tch::nn::{ModuleT, OptimizerConfig};

// Custom sequential network

fn create_network(vs: &nn::VarStore) -> nn::Sequential {

let root = vs.root();

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&root, 2, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 8, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root, 8, 2, Default::default()))

}

// Function to generate circular dataset

fn generate_dataset(n_samples: usize) -> (Vec<[f64; 2]>, Vec<i64>) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut data = Vec::new();

let mut labels = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..n_samples {

let r = rng.gen_range(0.0..2.0);

let theta = rng.gen_range(0.0..(2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI));

let x = r * theta.cos();

let y = r * theta.sin();

data.push([x, y]);

labels.push(if r < 1.0 { 0 } else { 1 });

}

(data, labels)

}

// Function to train and evaluate network with different optimizers

fn train_network(

net: &nn::Sequential,

data: &Tensor,

labels: &Tensor,

vs: &nn::VarStore,

learning_rate: f64,

optimizer_name: &str,

) -> (f64, Vec<f64>) {

let mut loss_history = Vec::new();

// Create optimizer based on name

let mut opt = match optimizer_name {

"Sgd" => nn::Sgd::default().build(vs, learning_rate).unwrap(),

"Adam" => nn::Adam::default().build(vs, learning_rate).unwrap(),

"RmsProp" => nn::RmsProp::default().build(vs, learning_rate).unwrap(),

_ => panic!("Unsupported optimizer"),

};

for epoch in 1..=1500 {

// Forward pass

let preds = net.forward_t(data, true);

// Compute loss

let loss = preds.cross_entropy_for_logits(labels);

// Backward pass and optimization

opt.zero_grad();

loss.backward();

opt.step();

// Record loss every 10 epochs

if epoch % 10 == 0 {

loss_history.push(loss.double_value(&[]));

}

}

// Compute accuracy

let preds = net.forward_t(data, false).argmax(1, false);

let accuracy = preds.eq_tensor(labels).to_kind(Kind::Float).mean(Kind::Float);

(accuracy.double_value(&[]) * 100.0, loss_history)

}

// Function to visualize loss curves

fn visualize_loss_curves(

loss_histories: &[(&str, Vec<f64>)],

accuracies: &[(&str, f64)],

) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let filename = "optimizer_comparison.png";

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (800, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Optimizer Performance Comparison", ("sans-serif", 30))

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0usize..50, 0.0..2.0)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

// Plot loss curves

for (i, (name, loss_history)) in loss_histories.iter().enumerate() {

let color = match i {

0 => &BLUE,

1 => &RED,

2 => &GREEN,

_ => &BLACK,

};

chart.draw_series(

loss_history.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, &y)|

Circle::new((x, y), 2, color.filled())

)

)?.label(format!("{} (Acc: {:.2}%)", name, accuracies[i].1))

.legend(move |(x, y)|

Circle::new((x, y), 5, color.filled())

);

}

chart.configure_series_labels()

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()?;

root.present()?;

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Set random seed for reproducibility

tch::maybe_init_cuda();

// Generate dataset

let (data, labels) = generate_dataset(1000);

let data_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice2(&data)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

let labels_tensor: Tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&labels)

.to_kind(Kind::Int64)

.to_device(Device::Cpu);

// Optimizers to compare

let optimizers = ["Sgd", "Adam", "RmsProp"];

// Store loss histories and accuracies

let mut loss_histories = Vec::new();

let mut accuracies = Vec::new();

// Compare different optimizers

for name in &optimizers {

println!("\nTraining with {} optimizer", name);

// Create VarStore and network

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let net = create_network(&vs);

// Train network

let (accuracy, loss_history) = train_network(

&net,

&data_tensor,

&labels_tensor,

&vs,

1e-3,

name

);

loss_histories.push((name.to_string(), loss_history));

accuracies.push((name.to_string(), accuracy));

println!("Accuracy with {}: {:.2}%", name, accuracy);

}

// Convert to slices for visualization

let loss_histories_slice: Vec<_> = loss_histories

.iter()

.map(|(name, history)| (name.as_str(), history.clone()))

.collect();

let accuracies_slice: Vec<_> = accuracies

.iter()

.map(|(name, accuracy)| (name.as_str(), *accuracy))

.collect();

// Visualize loss curves

visualize_loss_curves(&loss_histories_slice, &accuracies_slice)?;

println!("\nOptimizer comparison visualization saved!");

Ok(())

}

The experiment generates a synthetic dataset where points are labeled as belonging to one of two classes based on their distance from the origin. A multi-layer perceptron with three hidden layers is trained using each optimizer (SGD, Adam, and RMSprop). The training process records the cross-entropy loss at regular intervals, which is then plotted as loss curves for each optimizer. Additionally, the accuracy of the final model is calculated and displayed on the visualization to assess the impact of the optimizer on model performance.

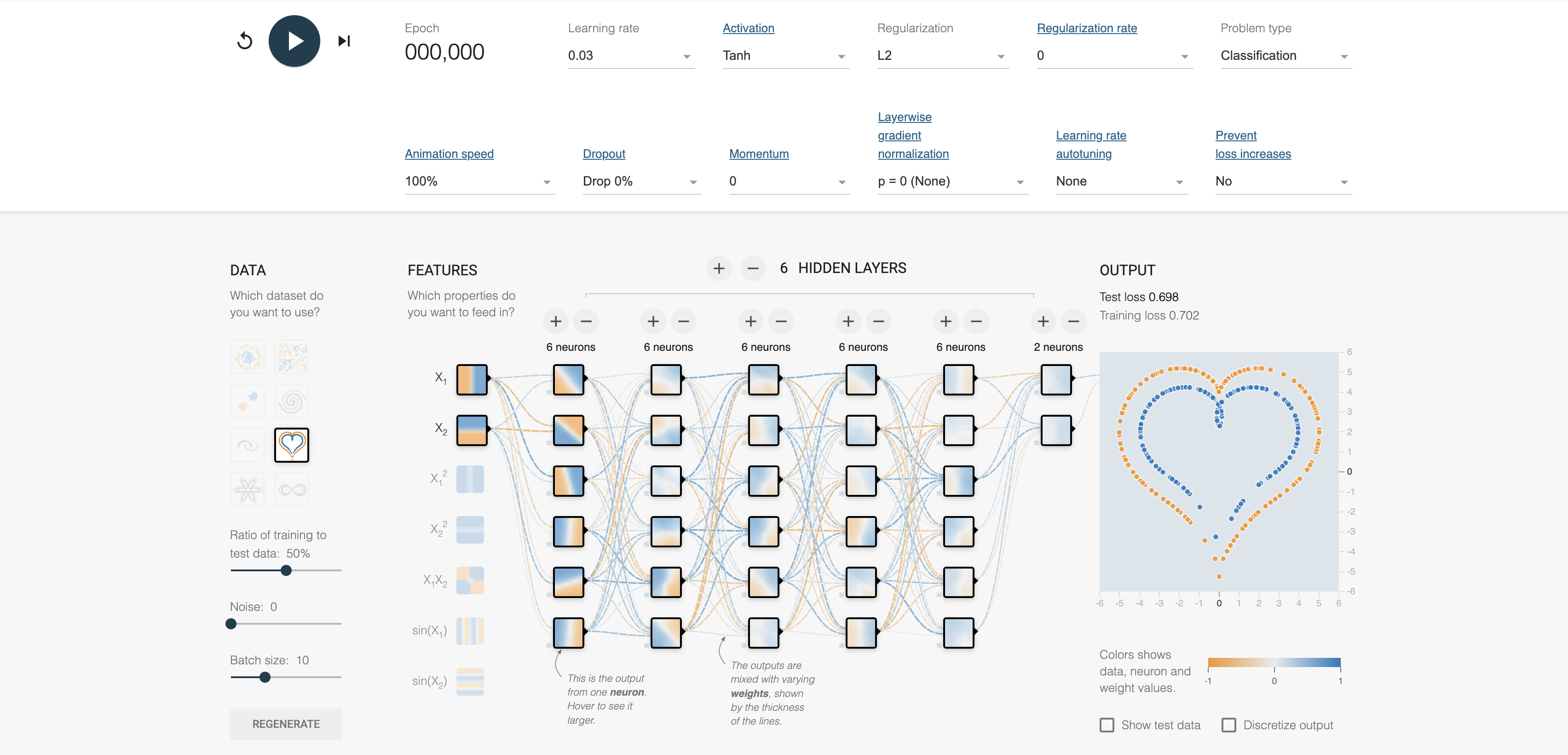

Figure 5: Plotters visualization of optimizer’s performance (SGD, Adam, RMSProp).

The chart visualizes the loss curves for each optimizer. SGD converges slowly and achieves the lowest accuracy (64.90%) due to its fixed learning rate and lack of momentum. Adam, leveraging adaptive learning rates and momentum, converges faster and reaches higher accuracy (98.60%). RMSprop, with its ability to adapt learning rates and smooth gradients for non-convex optimization, achieves the fastest convergence and highest accuracy (99.90%). These results highlight the significance of using adaptive optimizers for complex tasks and noisy gradients.

Optimization techniques are the cornerstone of deep RL, enabling neural networks to learn robust policies and value functions in challenging environments. The integration of advanced algorithms with stability-enhancing strategies like gradient clipping ensures efficient and scalable learning, making them indispensable for modern RL systems.

15.4. Neural Network Architectures

Neural network architectures form the foundation of deep learning, providing the structural design necessary to process diverse data types and perform complex computational tasks. In reinforcement learning (RL), the architecture of the neural network plays a crucial role in determining the agent's ability to learn, adapt, and generalize. Each architecture is tailored to specific tasks and data characteristics, influencing how policies, value functions, and state representations are modeled. Selecting the right architecture is vital for enabling agents to effectively navigate and make decisions in their environments.

Feedforward networks, often referred to as fully connected networks, are the most basic architecture. These networks process data in a linear, forward flow from input to output, making them ideal for tasks where the data is already structured or where feature extraction is minimal. Despite their simplicity, they excel in modeling basic policies and value functions in RL. For instance, a feedforward network can be used in environments with well-defined states and actions, where it learns to map inputs directly to outputs.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) extend this capability by introducing spatial awareness, making them indispensable for tasks involving visual data. In RL, CNNs are often employed in environments where agents perceive the world through images, such as video games or robotics. By capturing spatial hierarchies and patterns, CNNs enable agents to extract meaningful features from raw pixel data, such as identifying objects or understanding spatial relationships, enhancing decision-making in visually rich environments.

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, address scenarios where data has a temporal dimension or where the full state of the environment is not observable at a single timestep. These networks maintain a hidden state that evolves over time, allowing them to encode sequences of observations and infer long-term dependencies. In RL, this ability is critical for partially observable environments, such as tracking moving targets or navigating through uncertain terrains.

Attention-based models, including Transformers, represent the latest evolution in neural network architectures. These models excel at capturing long-range dependencies and relationships by selectively focusing on relevant parts of the input. In RL, attention mechanisms have proven valuable in tasks requiring complex reasoning or where agents must process multiple inputs simultaneously, such as multi-agent systems or dynamic resource allocation problems.

In practical implementations using Rust, these architectures can be implemented easily with frameworks like tch-rs or ndarray. Rust's emphasis on performance and safety ensures that neural networks can be trained and deployed efficiently, even in resource-constrained environments. Modular design in Rust enables the seamless combination of different architectural components, such as integrating CNNs with RNNs for hybrid tasks. By leveraging these principles and tools, RL practitioners can design robust neural network architectures tailored to the specific needs of their agents, unlocking new levels of performance and adaptability in complex, real-world environments.

Feedforward neural networks are the simplest and most foundational type of neural network, where information flows in one direction—from input to output—through a series of layers without cycles or loops. Each layer applies a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation function. Mathematically, an FNN is represented as:

$$ f_\theta(\mathbf{x}) = \sigma(\mathbf{W}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}), $$

where $\mathbf{W}$ is the weight matrix, $\mathbf{b}$ is the bias vector, $\sigma$ is an activation function such as ReLU or Sigmoid, and $\theta = \{\mathbf{W}, \mathbf{b}\}$ denotes the network parameters. FNNs are particularly effective in RL tasks where inputs are dense feature vectors, such as in tabular environments or when the state representation is inherently low-dimensional. They are commonly used to approximate value functions or policies in problems where the state and action spaces are manageable in size.

Figure 6: Illustration of FNN from DeeperPlayground tool (Ref:)

A feed-forward neural network processes input data by passing it through multiple layers of interconnected neurons. Each layer applies a weighted transformation followed by a non-linear activation function to capture complex patterns in the data. In the illustration image, the neural network takes two input features ($X_1$ and $X_2$) and processes them through six hidden layers with six neurons each, transforming the data progressively. The lines between neurons represent weights, with thickness indicating their magnitude, and the blue-orange colors depict the activation values. The final layer outputs predictions, here visualized as a classification of points into two classes (blue and orange) forming a heart-shaped boundary. The network's training minimizes loss by adjusting weights iteratively, achieving a balance between training and test performance as shown by the loss values.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are designed to process data with a known grid-like topology, such as images, audio spectrograms, or spatial observations in grid-based environments. CNNs employ convolutional layers that apply filters (kernels) to local regions of the input, capturing spatial hierarchies and local correlations. A convolution operation for a two-dimensional input is defined as:

$$ z_{i,j} = (\mathbf{W} * \mathbf{X})_{i,j} + b = \sum_{k,l} w_{k,l} \, x_{i+k, j+l} + b, $$

where $\mathbf{W}$ is the filter matrix, $\mathbf{X}$ is the input matrix, $w_{k,l}$ are the filter weights, $x_{i+k, j+l}$ is the input value at position $(i+k, j+l)$, and $b$ is the bias term. CNNs are parameter-efficient due to weight sharing and are inherently translationally invariant, making them well-suited for RL tasks involving visual data, such as playing video games or robotic vision applications. In these tasks, the agent must interpret high-dimensional sensory inputs and extract relevant features to inform decision-making.

Figure 7: Illustration of convolutional neural networks from CNN Explainer (Ref:https://poloclub.github.io/cnn-explainer)

A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) processes input data, such as images, by extracting hierarchical patterns through layers of convolutional and pooling operations. The diagram from the CNN Explainer, illustrates how an input image (a coffee cup) is passed through the network's layers. Initially, the image is decomposed into its red, green, and blue channels. Convolutional layers then apply filters to detect edges, textures, and other features, with activations visualized as intensity maps. These features are refined through multiple convolutional and ReLU (activation) layers, and pooling layers reduce spatial dimensions to retain only the most significant information. The network progressively builds a feature hierarchy, with later layers capturing complex patterns, such as the cup's overall shape. Finally, the output layer assigns probabilities to predefined classes (e.g., "espresso" or "orange"), indicating the network's classification decision. This structured feature extraction enables CNNs to recognize intricate visual patterns effectively.

Recurrent neural networks are specialized for processing sequential data, where the current output depends not only on the current input but also on the sequence of previous inputs. RNNs introduce the concept of a hidden state that captures information from prior time steps. The hidden state $\mathbf{h}_t$ at time $t$ is updated using:

$$ \mathbf{h}_t = f(\mathbf{W}_h \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{W}_x \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{b}), $$

where $\mathbf{h}_{t-1}$ is the hidden state from the previous time step, $\mathbf{x}_t$ is the current input, $\mathbf{W}_h$ and $\mathbf{W}_x$ are weight matrices for the hidden state and input, respectively, and $f$ is an activation function. However, standard RNNs struggle with learning long-term dependencies due to the vanishing or exploding gradient problem.

Long Short-Term Memory networks address this limitation by incorporating gating mechanisms that regulate the flow of information:

$$ \begin{align*}\mathbf{f}_t &= \sigma(\mathbf{W}_f \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{U}_f \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}_f), \\ \mathbf{i}_t &= \sigma(\mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{U}_i \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}_i), \\ \mathbf{o}_t &= \sigma(\mathbf{W}_o \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{U}_o \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}_o), \\ \mathbf{c}_t &= \mathbf{f}_t \odot \mathbf{c}_{t-1} + \mathbf{i}_t \odot \tanh(\mathbf{W}_c \mathbf{x}_t + \mathbf{U}_c \mathbf{h}_{t-1} + \mathbf{b}_c), \\ \mathbf{h}_t &= \mathbf{o}_t \odot \tanh(\mathbf{c}_t), \end{align*} $$

where $\mathbf{f}_t$, $\mathbf{i}_t$, and $\mathbf{o}_t$ are forget, input, and output gates, respectively; $\mathbf{c}_t$ is the cell state; and $\odot$ denotes element-wise multiplication. LSTMs are capable of capturing long-term dependencies, making them suitable for RL tasks involving partially observable environments, where the agent must remember information over time to make optimal decisions.

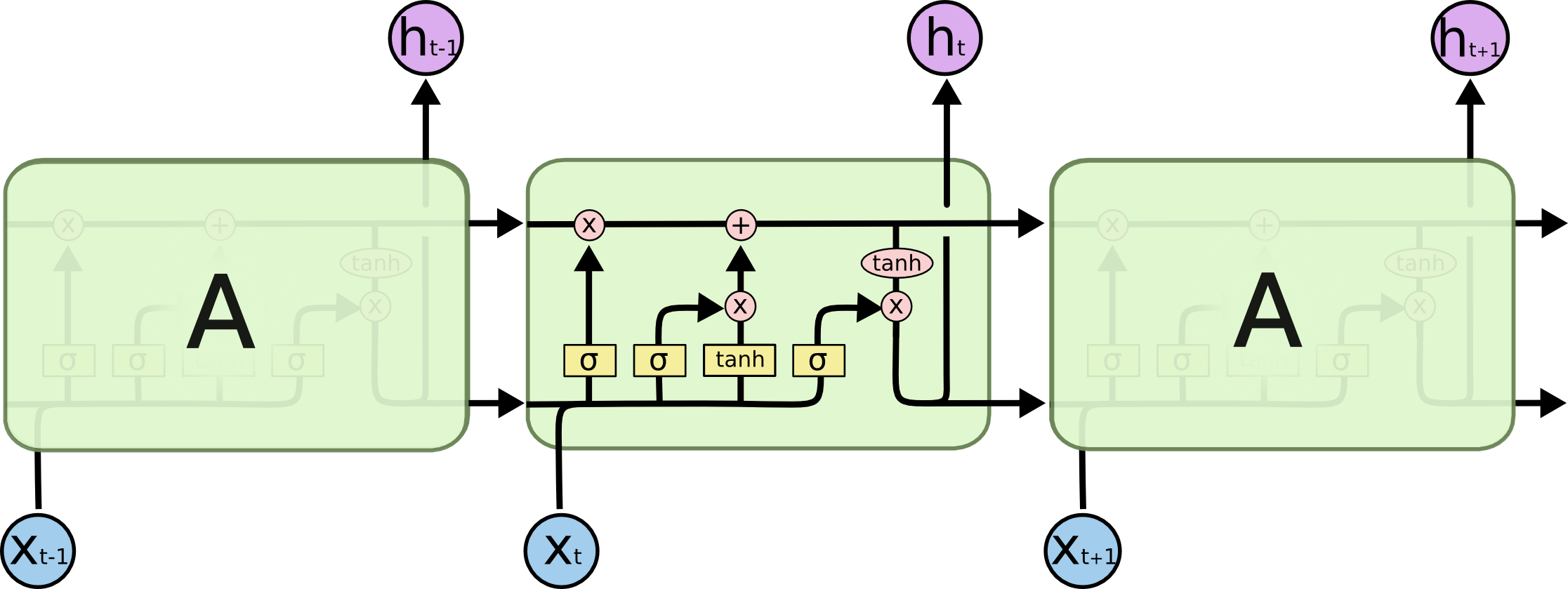

Figure 8: Illustration of LSTM from Colah’s blog (Ref: https://colah.github.io/posts/2015-08-Understanding-LSTMs)

LSTMs are designed to handle sequential data by processing one input at a time while maintaining a hidden state that carries information across time steps. The image illustrates the flow of information in an LSTM. At each time step $t$, the LSTM receives the current input ($X_t$) and combines it with the hidden state from the previous time step ($h_{t-1}$). This combination is passed through activation functions, typically $\tanh$ or $\sigma$ (sigmoid), to compute the updated hidden state ($h_t$). The process repeats for subsequent time steps, allowing the LSTM to model dependencies in the sequence. The loop-like structure of the LSTM enables it to "remember" past information and apply it to current computations, making it ideal for tasks like natural language processing and time series analysis.

Attention mechanisms enhance sequence modeling by allowing models to focus selectively on parts of the input sequence when generating each part of the output sequence. The core idea is to compute a weighted sum of values $\mathbf{V}$, where the weights are determined by the similarity between queries $\mathbf{Q}$ and keys $\mathbf{K}$. The attention function is defined as:

$$ \text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{\mathbf{Q} \mathbf{K}^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) \mathbf{V}, $$

where $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors, ensuring that the dot products do not become too large. Attention mechanisms enable models to capture dependencies regardless of their distance in the sequence, overcoming the limitations of fixed-size context windows in traditional RNNs.

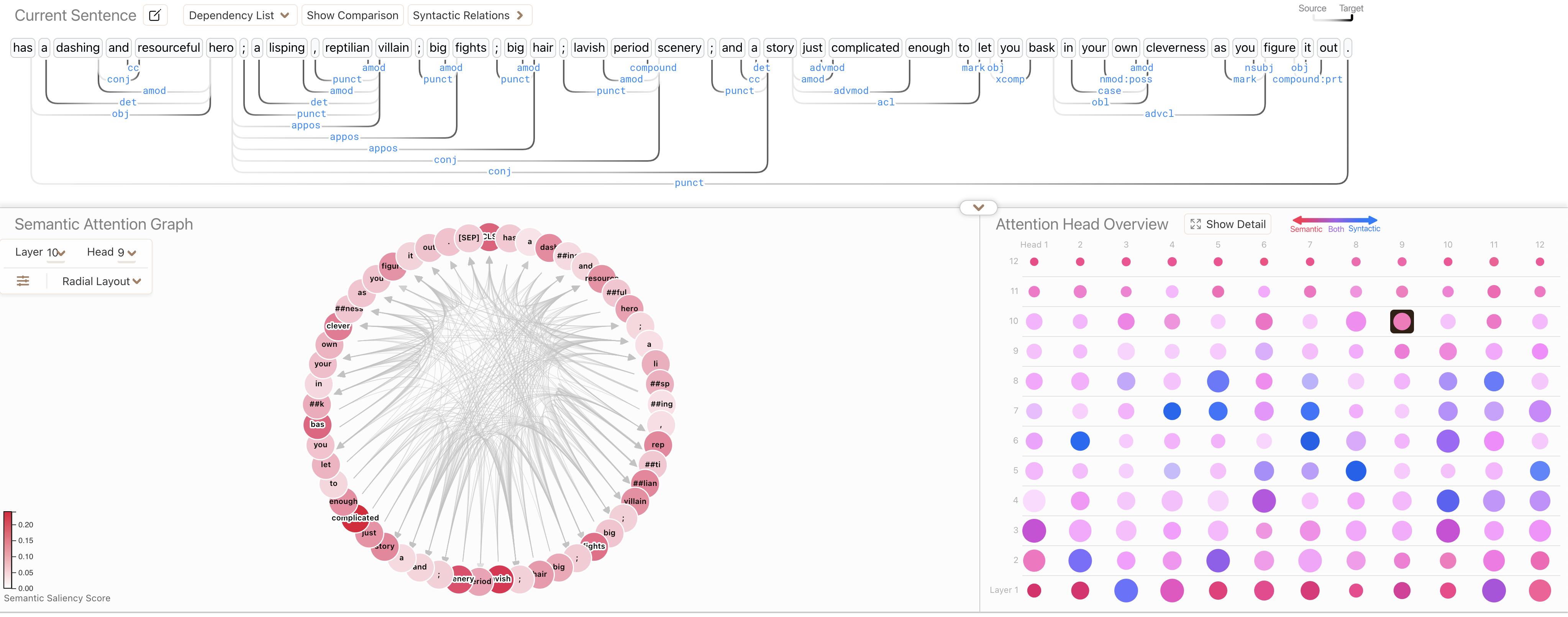

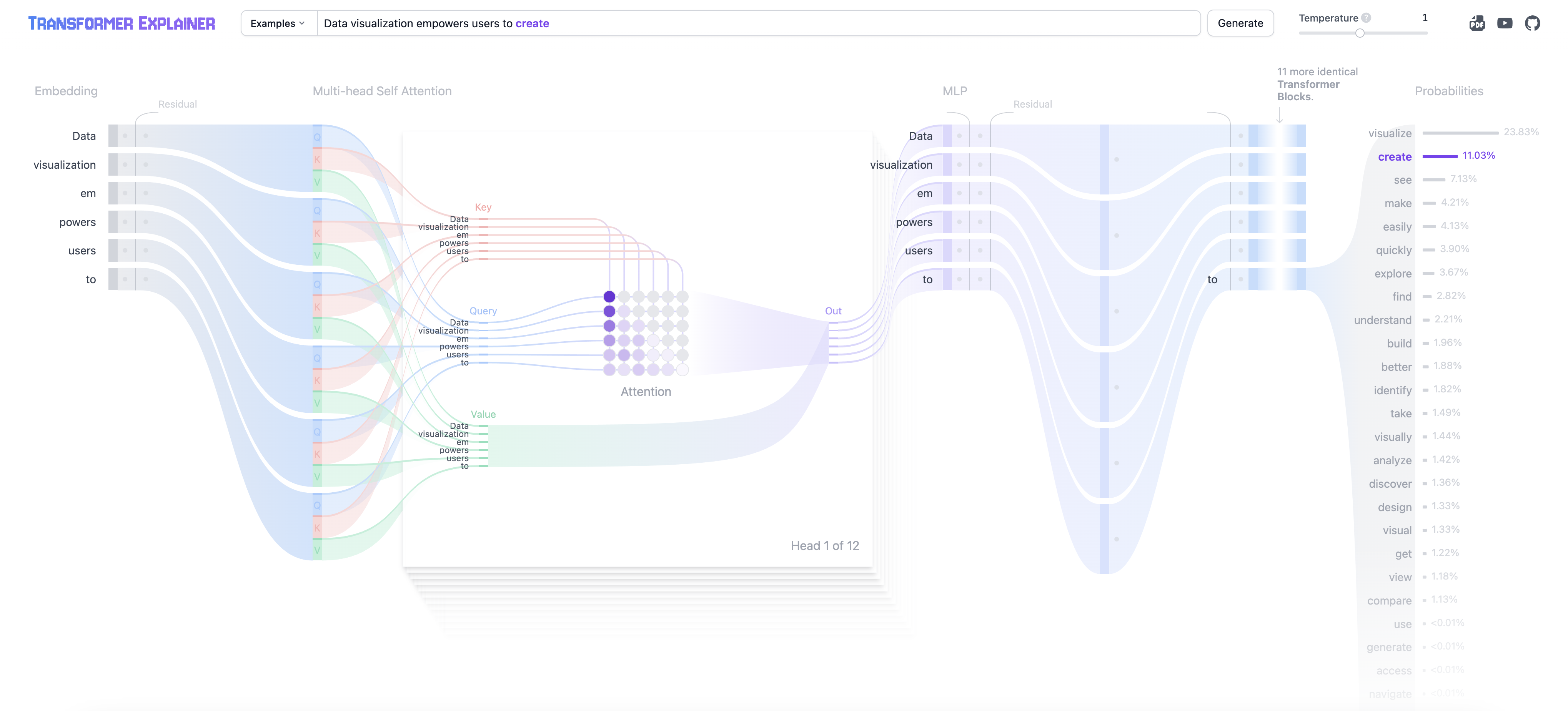

Figure 9: Illustration of attention and multi-head attention from Dodrio (ref: https://poloclub.github.io/dodrio)

Attention and multi-head attention mechanisms, as visualized in the Dodrio interface, are foundational to transformer models like BERT. Attention assigns weights to different parts of the input sequence, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant words or tokens for a given context. For example, in the sentence shown, words like "hero" and "villain" are highlighted as carrying more semantic importance relative to other tokens, influencing downstream tasks like text classification or translation.

Multi-head attention extends this mechanism by enabling the model to focus on multiple aspects of the input simultaneously. Each attention head captures different relationships, such as syntactic (e.g., dependency structure between words) or semantic (e.g., meaning and context of words). In the radial layout, each node represents a token, and the connections depict attention weights learned by a specific head in layer 10. The varying thickness and color intensity of the connections indicate the strength of attention weights, with darker connections showing higher focus. The attention head overview provides a summary of all heads in the model, indicating which heads prioritize semantic (red), syntactic (blue), or both types of information.

This combination of multiple attention heads helps the model capture richer representations of the input, balancing both global (long-term dependencies) and local (context-specific) relationships, enhancing its ability to perform tasks like language understanding and generation effectively.