Chapter 17

Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning

"You cannot understand complex systems by focusing solely on their parts; you must understand the hierarchies and relationships that bind them together." — Herbert A. Simon

Chapter 17 delves into Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL), a cutting-edge approach that extends traditional reinforcement learning by incorporating temporal abstractions and multi-level decision hierarchies. HRL addresses the limitations of flat RL methods, such as sample inefficiency and difficulty in solving long-horizon tasks, by decomposing complex problems into manageable sub-tasks with well-defined subgoals and macro-actions. This chapter begins with the mathematical foundations of HRL, including Semi-Markov Decision Processes (SMDPs) and nested Bellman equations, establishing a formal framework for hierarchical decision-making. It then explores advanced architectures such as actor-critic frameworks for multi-level policies, feudal reinforcement learning for hierarchical control, and skill discovery mechanisms for learning reusable options. The chapter also examines critical challenges like optimization stability, abstraction granularity, and reward shaping, while introducing innovations like parallelism, variance reduction techniques, and meta-learning for adaptive sub-policy discovery. Through practical, hands-on implementations in Rust, readers will gain the tools to build modular, scalable HRL systems and apply them to real-world domains such as robotics, multi-agent systems, and dynamic resource management, highlighting HRL's potential to transform intelligent decision-making across industries.

17.1. Introduction to Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning

Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) has emerged as a pivotal advancement in the field of reinforcement learning, addressing some of its most pressing challenges related to complexity, scalability, and efficiency. Traditional reinforcement learning methods often struggle when faced with tasks that require long-term planning or involve sparse and delayed rewards. HRL tackles these issues by introducing a hierarchical structure to the decision-making process, allowing agents to break down complex tasks into simpler, more manageable sub-tasks. This approach leverages the concept of temporal abstraction, enabling agents to plan and act over extended time horizons, which significantly enhances their ability to solve intricate problems.

The evolution of HRL is rooted in the necessity to overcome the limitations of flat reinforcement learning architectures. In conventional RL, agents learn policies that map states directly to actions, which can be inefficient and impractical for complex environments with vast state and action spaces. Early attempts to address this involved incorporating function approximators and deep neural networks, leading to the rise of Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). While DRL achieved remarkable success in various domains, such as playing Atari games and mastering Go, it still faced hurdles when dealing with tasks requiring hierarchical planning or multi-level decision-making.

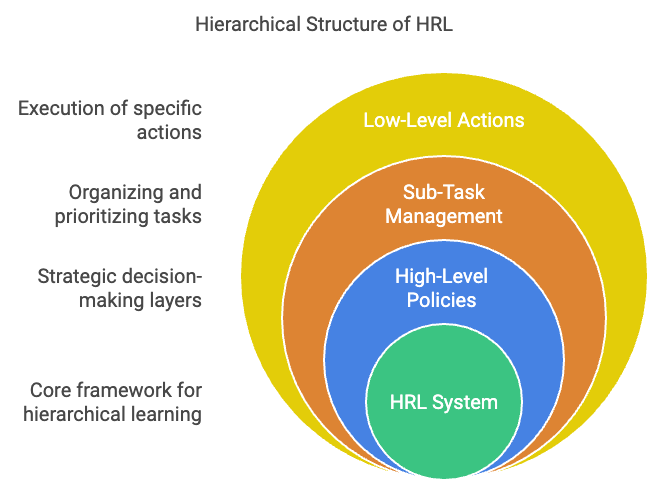

Figure 1: Scopes and structures of HRL model.

HRL builds upon these foundations by introducing hierarchy into the learning process. One of the key motivations behind HRL is the way humans and animals naturally approach problem-solving by decomposing tasks into sub-tasks or routines. For example, when planning a trip, one might first book flights, then arrange accommodation, and finally plan daily activities. Each of these steps can be further broken down into smaller actions. By mimicking this hierarchical approach, HRL enables agents to learn high-level policies that govern low-level actions, effectively managing complexity and improving learning efficiency.

The features of HRL can be broadly categorized into architectural abstractions and learning mechanisms. Architecturally, HRL introduces multiple layers or levels of policies:

High-Level Policies (Meta-Controller): These policies operate over extended time scales and make decisions about which sub-tasks or options to execute. They focus on long-term goals and strategic planning.

Low-Level Policies (Controllers): These policies handle the execution of specific sub-tasks, dealing with immediate actions and short-term objectives within the context defined by the high-level policies.

This hierarchical structure allows the agent to focus on different aspects of the task at appropriate levels of abstraction, leading to more efficient exploration and exploitation of the environment.

One prominent framework within HRL is the Options Framework, which defines options as temporally extended actions or macro-actions. An option includes a policy for selecting primitive actions, a termination condition, and an initiation set specifying where the option can be initiated. By learning and utilizing options, agents can plan over a longer horizon and reuse valuable behaviors across different tasks.

Another significant development in HRL is the Feudal Reinforcement Learning approach, where higher-level managers set goals or sub-goals for lower-level workers. The workers then learn policies to achieve these sub-goals. This hierarchical delegation mirrors organizational structures in human enterprises, promoting specialization and efficiency.

The motivation for HRL also stems from the desire to improve sample efficiency and overcome the curse of dimensionality in RL. By decomposing tasks, HRL reduces the effective complexity that the agent needs to handle at any given level. This decomposition allows for:

Modular Learning: Components of the hierarchy can be learned separately or reused across different tasks, facilitating transfer learning and reducing the need to learn from scratch.

Improved Exploration: High-level policies can guide exploration more effectively by focusing on meaningful sub-tasks, reducing the randomness associated with naive exploration strategies.

Handling Sparse Rewards: By defining intrinsic rewards or sub-goals at lower levels, HRL helps agents receive more frequent feedback, alleviating the challenges posed by sparse and delayed rewards in traditional RL.

In practical implementations, HRL has demonstrated success in a variety of complex domains. For instance, in robotic manipulation tasks, HRL enables robots to perform sequences of movements that require coordination over time, such as assembling objects or navigating in dynamic environments. In natural language processing, HRL has been used to model hierarchical structures in language generation and dialogue systems.

Moreover, HRL aligns well with the concept of transfer learning. Since sub-policies or options represent reusable skills, they can be transferred to new tasks that share similar structures or sub-tasks. This capability significantly reduces the training time required for new tasks and enhances the generalization of the learning agent.

In conclusion, Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning represents a powerful extension of traditional RL methods, addressing key challenges related to complexity, scalability, and efficiency. By introducing hierarchical structures and temporal abstraction, HRL empowers agents to decompose complex tasks into manageable sub-tasks, plan over extended time horizons, and leverage modular learning components. This approach not only improves learning efficiency and performance in complex environments but also opens up new possibilities for applying reinforcement learning to real-world problems that were previously intractable with conventional methods.

Hierarchical reinforcement learning can be formally defined as a nested optimization problem, where an overarching high-level policy governs decision-making at a macro level while delegating execution details to low-level sub-policies. This hierarchical decomposition can be expressed mathematically as:

$$ \pi(s) \rightarrow \pi_{high}(s) \rightarrow \pi_{low}(s, o), $$

where $\pi(s)$ is the overall policy, $\pi_{high}(s)$ is the high-level policy that selects macro-actions or subgoals $o$, and $\pi_{low}(s, o)$ is the low-level policy that executes actions to achieve the chosen subgoal.

Temporal abstraction in HRL relies on the framework of Semi-Markov Decision Processes (SMDPs), an extension of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) that incorporates temporally extended actions. In SMDPs, options $\mathcal{O}$ are defined as:

$$ \mathcal{O} = (\mathcal{I}, \pi, \beta), $$

where:

$\mathcal{I}$: The initiation set, specifying states where the option can be started.

$\pi$: The intra-option policy, guiding actions within the option.

$\beta(s)$: The termination condition, determining the probability of completing the option in state $s$.

The hierarchical Bellman equation is used to optimize policies across multiple levels:

$$ Q_{high}(s, o) = \mathbb{E} \left[ r + \gamma^k Q_{high}(s', o') \right], $$

where $k$ represents the duration of the option, $r$ is the cumulative reward, and $Q_{high}(s, o)$ reflects the value of selecting option $o$ in state $s$.

HRL architectures consist of high-level controllers and low-level sub-policies, each operating at different temporal and spatial resolutions. High-level controllers select subgoals, leveraging abstract representations of the environment, while low-level policies execute specific actions to achieve these subgoals. This division allows the system to operate efficiently across multiple scales of decision-making.

Subgoals play a critical role in HRL, acting as intermediate milestones that guide agents toward achieving long-term objectives. By focusing on achieving subgoals, the agent simplifies the learning process, as it does not need to optimize directly for distant rewards.

HRL also provides a natural framework for multi-level decision hierarchies, where options, skills, and task decompositions define distinct layers of abstraction. These abstractions allow agents to generalize learned behaviors across tasks, significantly improving reusability and scalability.

The following Rust implementation demonstrates a simple HRL framework with high-level and low-level policies. The HRL model decomposes complex decision-making tasks into two levels: a high-level policy and a low-level policy. The high-level policy defines goals or subgoals based on the current state of the environment, while the low-level policy generates specific actions to achieve these goals. This hierarchical structure allows the agent to tackle long-horizon tasks by focusing on intermediate objectives, significantly improving learning efficiency and scalability. The HRL framework effectively abstracts actions into meaningful subgoals, making it suitable for complex environments requiring multitask learning and coordination.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor};

use plotters::prelude::*;

// Define constants

const STATE_DIM: i64 = 4; // Dimensionality of the state vector

const ACTION_DIM: i64 = 2; // Dimensionality of the action vector

const GOAL_DIM: i64 = 2; // Dimensionality of the goal vector

const EPISODES: usize = 1000; // Number of episodes to train

const MAX_STEPS: usize = 50; // Maximum steps per episode

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99; // Discount factor for future rewards

// Visualization function for rewards

fn visualize_rewards(rewards: &[f64], filename: &str) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (1280, 720)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Rewards per Episode", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..rewards.len(), rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::min)..rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::INFINITY, f64::max))

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(i, &r)| (i, r)),

&RED,

))

.unwrap()

.label("Reward")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 10, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels().draw().unwrap();

}

// Define the high-level policy network that generates goals

fn high_level_policy(vs: &nn::Path) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "hl_layer1", STATE_DIM, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "hl_layer2", 128, GOAL_DIM, Default::default()))

}

// Define the low-level policy network that generates actions based on the state and goal

fn low_level_policy(vs: &nn::Path, goal_dim: i64) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "ll_layer1", STATE_DIM + goal_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "ll_layer2", 128, ACTION_DIM, Default::default()))

}

// Define a linear mapping layer that maps actions to state space

fn map_action_to_state(vs: &nn::Path) -> nn::Linear {

nn::linear(vs, ACTION_DIM, STATE_DIM, Default::default())

}

// Update the environment based on the current state and action

fn update_environment(state: &Tensor, action: &Tensor, map_layer: &nn::Linear) -> (Tensor, f64) {

let mapped_action = map_layer.forward(action);

let next_state = (state + mapped_action).detach();

let reward = -next_state.abs().sum(tch::Kind::Float).double_value(&[]);

(next_state, reward)

}

// Compute the action given the state and goal using the low-level policy

fn compute_action(state: &Tensor, goal: &Tensor, low_policy: &impl Module) -> Tensor {

let input = Tensor::cat(&[state.unsqueeze(0), goal.unsqueeze(0)], 1);

low_policy.forward(&input).squeeze().clamp(-1.0, 1.0)

}

// Perform gradient clipping to ensure stability in training

fn clip_gradients(var_store: &nn::VarStore, clip_value: f64) {

let mut total_norm: f64 = 0.0;

for (_name, var) in var_store.variables() {

let grad = var.grad();

total_norm += grad.norm().double_value(&[]).powi(2);

}

total_norm = total_norm.sqrt();

if total_norm > clip_value {

let scale = clip_value / total_norm;

let scale_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&[scale]);

for (_name, var) in var_store.variables() {

let mut grad = var.grad();

let _ = grad.f_mul_(&scale_tensor).unwrap();

}

}

}

fn main() {

const CLIP_VALUE: f64 = 1.0;

let device = Device::Cpu;

let hl_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let high_policy = high_level_policy(&hl_vs.root());

let mut hl_opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&hl_vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let ll_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let low_policy = low_level_policy(&ll_vs.root(), GOAL_DIM);

let mut ll_opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&ll_vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let map_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let map_layer = map_action_to_state(&map_vs.root());

let mut episode_rewards = vec![];

for episode in 0..EPISODES {

let mut state = Tensor::randn(&[STATE_DIM], (tch::Kind::Float, device));

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

let goal = high_policy.forward(&state.unsqueeze(0)).squeeze().detach();

for _ in 0..MAX_STEPS {

let action = compute_action(&state, &goal, &low_policy);

let (next_state, reward) = update_environment(&state, &action, &map_layer);

total_reward += reward;

ll_opt.zero_grad();

let target = Tensor::of_slice(&[reward]) + GAMMA

* low_policy

.forward(&Tensor::cat(&[next_state.unsqueeze(0), goal.unsqueeze(0)], 1))

.mean(tch::Kind::Float)

.detach();

let current_value = low_policy

.forward(&Tensor::cat(&[state.unsqueeze(0), goal.unsqueeze(0)], 1))

.mean(tch::Kind::Float);

let advantage = target - current_value;

let loss = (-advantage).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

loss.backward();

clip_gradients(&ll_vs, CLIP_VALUE);

ll_opt.step();

state = next_state;

}

hl_opt.zero_grad();

let hl_value = high_policy

.forward(&state.unsqueeze(0))

.mean(tch::Kind::Float);

let hl_target = Tensor::of_slice(&[total_reward]);

let hl_advantage = hl_target - hl_value;

let hl_loss = (-hl_advantage).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

hl_loss.backward();

clip_gradients(&hl_vs, CLIP_VALUE);

hl_opt.step();

episode_rewards.push(total_reward);

if episode % 10 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward: {}", episode, total_reward);

}

}

visualize_rewards(&episode_rewards, "rewards.png");

}

The high-level policy generates a goal vector from the current state using a neural network. This goal serves as input for the low-level policy, which, in combination with the current state, computes the action to be taken. The action is then mapped to the state space using a mapping layer, updating the environment to produce a new state and reward. The low-level policy is trained using the advantage function, where the temporal difference between the predicted and actual rewards is minimized. Simultaneously, the high-level policy is updated based on the accumulated total reward over an episode, ensuring alignment between the high-level and low-level objectives. Gradient clipping is employed to ensure stable learning.

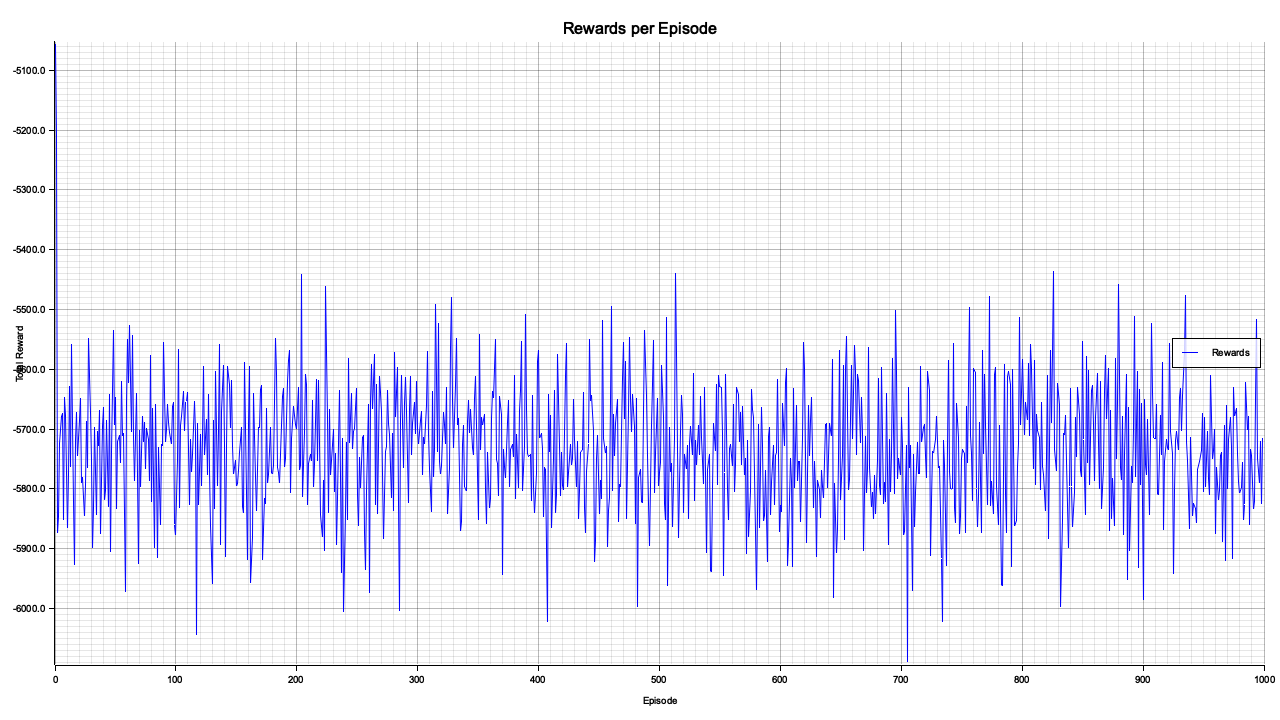

Figure 2: Plotters visualization of the HRL total reward per episode.

The chart depicts the total rewards achieved per episode during training. The fluctuating pattern indicates that the hierarchical reinforcement learning model is learning but with significant variability in performance across episodes. The lack of a clear upward trend in rewards suggests that the learning process may require further tuning, such as adjusting hyperparameters like the learning rate, discount factor (GAMMA), or gradient clipping threshold. The persistent oscillations could also indicate a challenging environment or instability in policy updates. Overall, while the model maintains activity throughout episodes, improvements in stability and performance optimization are needed to achieve more consistent and higher rewards.

This section introduced the core principles and implementations of Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. By decomposing complex tasks into high- and low-level policies, HRL enables agents to address long-term goals efficiently while maintaining adaptability in dynamic environments. Through Rust-based implementations, readers gain a hands-on understanding of the mathematical foundations, conceptual abstractions, and practical applications of HRL, setting the stage for solving increasingly complex real-world problems.

17.2. Mathematical Formulations and Temporal Abstractions in HRL

Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) represents a transformative advancement in reinforcement learning by introducing the ability to reason over multiple timescales. Traditional reinforcement learning methods often operate within the constraints of a single timescale, mapping states to actions in a one-step-at-a-time fashion. While effective for simpler problems, these methods struggle with complex tasks requiring long-term planning or involving sparse rewards that appear only after sequences of actions. HRL addresses these limitations by leveraging temporal abstractions, which allow agents to make decisions at different levels of granularity, facilitating both short-term action execution and long-term strategic planning.

The evolution of HRL stems from the need to overcome the limitations of flat RL architectures, where all decisions are treated as atomic actions. In these setups, the agent must explore and evaluate every possible action at each step, leading to inefficiencies in environments with large or continuous state and action spaces. To address this, HRL extends the decision-making framework from the standard Markov Decision Process (MDP) to the more flexible Semi-Markov Decision Process (SMDP). This extension allows for the incorporation of temporally extended actions, such as "navigate to the nearest door" or "pick up an object," which can consist of several primitive steps. These temporally extended actions, often referred to as options, provide a natural way to model sub-tasks within a larger task hierarchy.

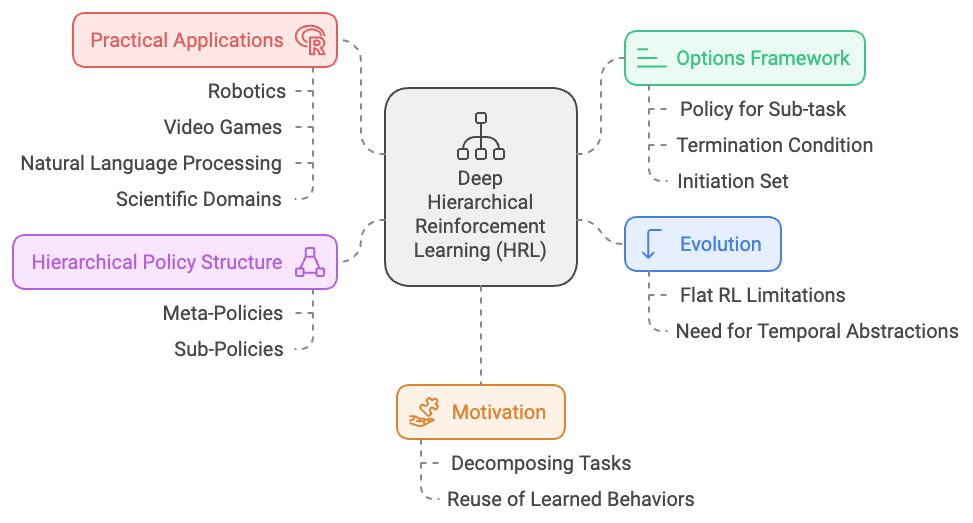

Figure 3: Deep HRL Model evolution, scopes, framework and applications.

A defining feature of HRL is its options framework, which formalizes the concept of temporally extended actions. Options consist of three components: a policy for executing the sub-task, a termination condition that defines when the sub-task ends, and an initiation set specifying the states in which the option can be initiated. This framework enables agents to break down a complex task into reusable and modular sub-tasks, promoting efficient exploration and reducing the overall problem complexity. For instance, in robotic control, options might represent behaviors like grasping an object, navigating to a target, or avoiding an obstacle. By learning these options independently or hierarchically, agents can develop robust behaviors that can be combined and adapted to solve new, unseen tasks.

Another significant feature of HRL is its hierarchical policy structure, which introduces multiple layers of decision-making. At the higher level, meta-policies govern which options or sub-tasks to execute, effectively acting as strategic planners. At the lower level, sub-policies or controllers execute the chosen options, handling fine-grained action selection and interacting directly with the environment. This division of responsibilities allows HRL agents to plan and execute over extended time horizons, making them well-suited for tasks with delayed rewards or requiring sequential reasoning. For example, a high-level policy in a navigation task might decide on the sequence of waypoints to reach a destination, while the low-level policy manages the immediate motor actions to follow the path.

The motivation behind HRL is deeply rooted in how humans and animals approach problem-solving. People naturally decompose complex tasks into smaller, manageable sub-tasks, solving them sequentially or in parallel. This hierarchical structure not only reduces cognitive load but also allows for the reuse of learned behaviors across different contexts. HRL brings this same principle to artificial agents, enabling them to generalize learned skills and transfer them to new problems. For example, once an agent has learned how to "open a door," it can reuse this skill in various tasks without relearning it from scratch.

HRL also addresses the critical challenge of scalability in RL. By focusing on higher-level abstractions at the meta-policy level, HRL significantly reduces the number of decisions the agent needs to make, thereby improving sample efficiency. This is particularly valuable in environments with sparse rewards, where naive exploration can be prohibitively slow. By setting sub-goals or intrinsic rewards at lower levels, HRL enables agents to receive frequent feedback, accelerating the learning process. Furthermore, HRL facilitates modularity, where individual sub-policies can be trained independently and later integrated into a cohesive hierarchical framework. This modularity enhances flexibility, making it easier to adapt or extend the agent's capabilities as new tasks or objectives arise.

In terms of practical applications, HRL has demonstrated remarkable success in domains requiring sequential reasoning and multi-step planning. In robotics, HRL enables robots to perform complex tasks such as assembling objects, navigating cluttered environments, or manipulating tools. In video games, HRL allows agents to strategize over long-term objectives while managing immediate in-game actions. In natural language processing, HRL has been applied to dialogue systems, where high-level policies determine conversational goals, and low-level policies generate specific responses. Additionally, HRL has shown promise in scientific domains, such as computational biology, where agents must design and execute multi-step experiments or simulations.

In conclusion, the evolution of HRL represents a significant shift in reinforcement learning by introducing temporal abstractions and hierarchical structures. By extending the decision-making framework to include options and nested policies, HRL provides a scalable and modular approach to tackling complex tasks. Its ability to balance long-term planning with immediate action execution makes it uniquely capable of handling environments with sparse rewards, large state-action spaces, and intricate dependencies between actions. HRL’s features and motivations reflect its roots in natural problem-solving strategies, offering a powerful paradigm for advancing reinforcement learning in real-world applications.

An SMDP is a generalization of an MDP that incorporates temporally extended actions. While an MDP models the environment as a sequence of discrete state-action pairs, an SMDP accounts for actions that may span multiple timesteps. Formally, an SMDP is defined by:

A set of states $\mathcal{S}$,

A set of actions $\mathcal{A}$,

A transition probability $P(s' \mid s, a, \Delta t)$, where $\Delta t$ is the time duration of the action,

A reward function $R(s, a)$,

A discount factor $\gamma \in [0,1]$.

In this framework, the state transitions depend not only on the current state and action but also on the duration $\Delta t$ of the action, making it ideal for modeling hierarchical decision-making.

The options framework provides a structure for temporal abstractions in HRL. Each option $\mathcal{O}$ consists of:

An initiation set $\mathcal{I}$, which defines the states where the option can start.

An intra-option policy $\pi(a \mid s)$, which specifies the actions to take while the option is active.

A termination condition $\beta(s)$, which gives the probability of the option terminating in a given state.

The value function for an option $\mathcal{O}$ is defined as:

$$ Q_{\mathcal{O}}(s, o) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_k \mid s_0 = s, o_0 = o \right], $$

where $o$ represents the chosen option. Options enable agents to learn reusable sub-policies, simplifying the learning process in complex environments.

In HRL, policies are optimized hierarchically, with a high-level policy $\pi_{high}(o \mid s)$ selecting options and a low-level policy $\pi_{low}(a \mid s, o)$ executing actions to achieve the goals of the chosen option. The hierarchical Bellman equation is used to optimize these policies:

$$ Q_{high}(s, o) = \mathbb{E} \left[ r + \gamma^k Q_{high}(s', o') \right], $$

where $k$ is the duration of the option. This nested optimization enables agents to balance short-term and long-term objectives effectively.

The relationship between SMDPs and MDPs lies in the modeling of time. While MDPs assume instantaneous actions, SMDPs account for varying durations, making them more flexible for hierarchical decision-making. Temporal abstractions enable agents to plan over extended horizons by breaking tasks into manageable sub-tasks, each with its own policy. This multi-timescale decision-making approach allows for effective exploration at the high level while exploiting known strategies at the low level.

For instance, in a navigation task, the high-level policy might decide on subgoals (e.g., reach a specific room), while the low-level policy determines the detailed actions required to navigate to those subgoals. This separation of concerns improves learning efficiency and reduces computational complexity.

The presented model implements a Semi-Markov Decision Process (SMDP) solver with hierarchical policies designed to handle temporally extended options. The framework consists of two distinct policies: a high-level policy that selects goals based on the current state and a low-level policy tasked with executing actions to achieve the chosen goal. By enabling hierarchical decision-making, the model efficiently balances short-term and long-term objectives, optimizing performance in complex environments. This hierarchical approach also accommodates temporally extended options, allowing for efficient execution over multiple time steps.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor};

use plotters::prelude::*;

// Define constants

const STATE_DIM: i64 = 4; // Dimensionality of the state vector

const ACTION_DIM: i64 = 2; // Dimensionality of the action vector

const GOAL_DIM: i64 = 4; // Dimensionality of the goal vector (to match STATE_DIM)

const EPISODES: usize = 1000; // Number of episodes to train

const MAX_OPTION_STEPS: usize = 50; // Maximum steps per option

const TERMINATION_THRESHOLD: f64 = 0.1; // Threshold to determine goal achievement

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99; // Discount factor for future rewards

// Visualization function for rewards

fn visualize_rewards(rewards: &[f64], filename: &str) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (1280, 720)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let max_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let min_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::INFINITY, f64::min);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Rewards per Episode", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(15)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..rewards.len(), (min_reward - 5.0)..(max_reward + 5.0))

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh()

.x_desc("Episode")

.y_desc("Total Reward")

.draw()

.unwrap();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(i, &r)| (i, r)),

&BLUE,

))

.unwrap()

.label("Rewards")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 15, y)], &BLUE));

chart.configure_series_labels()

.border_style(&BLACK)

.background_style(&WHITE.mix(0.8))

.draw()

.unwrap();

}

// Define the high-level policy network

fn high_level_policy(vs: &nn::Path) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "hl_layer1", STATE_DIM, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "hl_layer2", 128, GOAL_DIM, Default::default()))

}

// Define the low-level policy network

fn low_level_policy(vs: &nn::Path, goal_dim: i64) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "ll_layer1", STATE_DIM + goal_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "ll_layer2", 128, ACTION_DIM, Default::default()))

}

// Define a mapping layer that maps actions to state space

fn map_action_to_state(vs: &nn::Path) -> nn::Linear {

nn::linear(vs, ACTION_DIM, STATE_DIM, Default::default())

}

// Update the environment based on the current state and action

fn update_environment(state: &Tensor, action: &Tensor, map_layer: &nn::Linear) -> (Tensor, f64) {

let mapped_action = map_layer.forward(action);

let next_state = (state + mapped_action).detach();

let reward = -next_state.abs().sum(tch::Kind::Float).double_value(&[]);

(next_state, reward)

}

// Compute the action given the state and goal

fn compute_action(state: &Tensor, goal: &Tensor, low_policy: &impl Module) -> Tensor {

let input = Tensor::cat(&[state.unsqueeze(0), goal.unsqueeze(0)], 1);

low_policy.forward(&input).squeeze().clamp(-1.0, 1.0)

}

// Execute an option dynamically

fn execute_option(

state: &mut Tensor,

goal: &Tensor,

low_policy: &impl Module,

map_layer: &nn::Linear,

max_steps: usize,

termination_threshold: f64,

) -> (Tensor, f64, usize) {

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

let mut duration = 0;

for step in 0..max_steps {

let action = compute_action(state, goal, low_policy);

let (next_state, reward) = update_environment(state, &action, map_layer);

total_reward += reward;

*state = next_state;

// Check termination condition

let goal_achieved = (&*state - goal).abs().sum(tch::Kind::Float).double_value(&[]) < termination_threshold;

if goal_achieved {

duration = step + 1;

break;

}

duration = step + 1;

}

(state.shallow_clone(), total_reward, duration)

}

// Main function

fn main() {

let device = Device::Cpu;

let hl_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let high_policy = high_level_policy(&hl_vs.root());

let mut hl_opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&hl_vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let ll_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let low_policy = low_level_policy(&ll_vs.root(), GOAL_DIM);

let map_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let map_layer = map_action_to_state(&map_vs.root());

let mut episode_rewards = vec![];

for episode in 0..EPISODES {

let mut state = Tensor::randn(&[STATE_DIM], (tch::Kind::Float, device));

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

for _ in 0..MAX_OPTION_STEPS {

// High-level policy selects a goal

let goal = high_policy.forward(&state.unsqueeze(0)).squeeze().detach();

// Execute the selected option

let (final_state, option_reward, option_duration) = execute_option(

&mut state,

&goal,

&low_policy,

&map_layer,

MAX_OPTION_STEPS,

TERMINATION_THRESHOLD,

);

total_reward += option_reward;

// Update high-level policy using the duration of the option

hl_opt.zero_grad();

let hl_value = high_policy.forward(&final_state.unsqueeze(0)).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

let discounted_reward = option_reward * GAMMA.powi(option_duration as i32);

let hl_target = Tensor::of_slice(&[discounted_reward]);

let hl_loss = (hl_target - hl_value).pow_tensor_scalar(2.0).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

hl_loss.backward();

hl_opt.step();

}

episode_rewards.push(total_reward);

if episode % 10 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward: {:.2}", episode, total_reward);

}

}

visualize_rewards(&episode_rewards, "smdp_rewards.png");

}

The high-level policy uses the current state to predict a goal, which acts as a sub-task for the low-level policy. The low-level policy is responsible for generating actions that drive the system toward the goal, interacting with the environment through mapped actions. The model includes an option termination condition that checks whether the goal has been achieved within a specified threshold. Additionally, rewards are discounted based on the duration of options, reflecting the temporal aspect of SMDP. Both policies are updated using gradient-based optimization, with the high-level policy leveraging the cumulative discounted rewards over the duration of an option, while the low-level policy focuses on immediate action rewards.

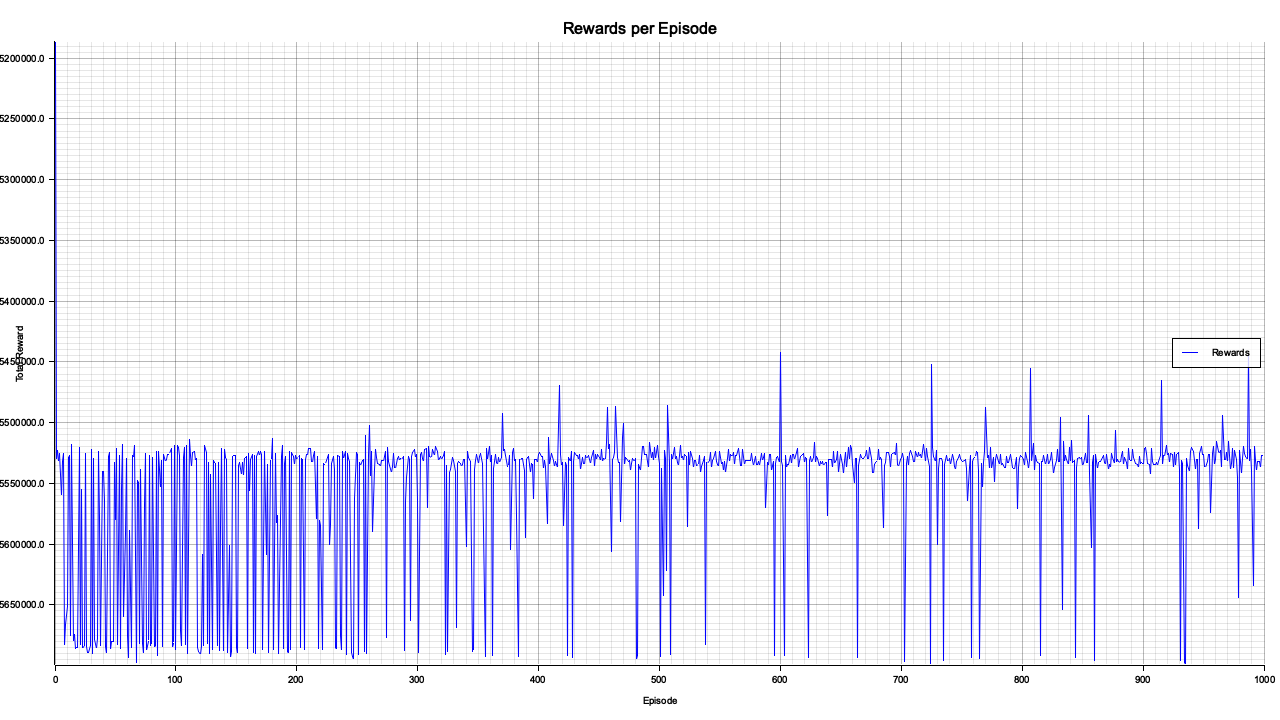

Figure 4: Plotters visualization of rewards per episode.

The reward per episode chart indicates the overall performance of the SMDP solver over 1000 episodes. The fluctuations in the reward suggest a degree of variability in goal selection and option execution, reflecting the complexity of hierarchical decision-making in the environment. Over time, the trend stabilizes, indicating that the model successfully learns a policy capable of consistently achieving higher rewards. Occasional dips in performance may be attributed to challenging goal selections or sub-optimal execution of options by the low-level policy. The convergence toward a more stable reward range demonstrates the efficacy of the hierarchical policy in managing the temporal and spatial complexities of the problem.

This section provides a rigorous exploration of the mathematical foundations and temporal abstractions that underpin HRL. By extending MDPs to SMDPs, defining options, and leveraging hierarchical policy optimization, HRL offers a structured approach to solving complex tasks. Practical implementations in Rust, including SMDP solvers and visualizations, illustrate the power and flexibility of temporal abstractions, equipping readers with the tools to design scalable and efficient HRL systems.

17.3. Architectures for Deep Hierarchical Models

Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) is powered by advanced architectures that combine the representational capacity of neural networks with the decision-making capabilities of hierarchical policies. These architectures, such as actor-critic models, feudal reinforcement learning (RL), and skill discovery frameworks, enable agents to tackle complex, multi-stage tasks by leveraging abstractions across multiple levels of decision-making. This section explores the mathematical underpinnings of HRL architectures, conceptual advancements in designing robust hierarchical frameworks, and practical implementations in Rust for solving real-world problems.

At the core of HRL architectures is the representation of hierarchical policies as deep neural networks. In HRL, policies are decomposed into high-level and low-level networks, each optimized to operate at different temporal and spatial resolutions. For a state sss, a high-level policy $\pi_{high}(o \mid s; \theta_{high})$ selects an option $o$, which is executed by a low-level policy $\pi_{low}(a \mid s, o; \theta_{low})$. Mathematically:

$$ \pi(s) \approx \pi_{high}(o \mid s; \theta_{high}) \cdot \pi_{low}(a \mid s, o; \theta_{low}), $$

where $\theta_{high}$ and $\theta_{low}$ are the parameters of the high-level and low-level policies, respectively.

The optimization of these hierarchical policies requires backpropagation through multiple levels. Gradients are computed independently for each level and combined to update the network parameters:

$$ \nabla J(\theta_{high}, \theta_{low}) = \nabla J(\theta_{high}) + \nabla J(\theta_{low}), $$

where $J(\theta)$ represents the objective function, typically the expected cumulative reward. This modular gradient computation allows HRL architectures to adapt to changes in the environment efficiently.

Actor-critic models are well-suited for HRL because they naturally decompose policy optimization into value-based and policy-based learning. In HRL, a high-level actor-critic selects options using a high-level policy (actor) and evaluates their value using a high-level value function (critic). The low-level policy network executes the selected option while being guided by its own value function. This structure ensures stability and efficiency in learning long-term strategies.

Feudal RL introduces a hierarchical master-worker architecture. The master policy sets subgoals for the worker policies, which operate in localized state-action spaces. Explicit reward sharing ensures that the workers' objectives align with the master's overall goals:

$$ R_{worker} = R_{master} + \alpha \cdot R_{local}, $$

where $R_{local}$ is the intrinsic reward for achieving the subgoal, and $\alpha$ balances local and global rewards.

Skill discovery frameworks focus on learning reusable sub-policies or "skills" that can be applied across multiple tasks. These skills are often learned through unsupervised techniques by identifying frequently occurring state-action patterns. For example, a skill $\mathcal{S}$ might be represented as:

$$ \mathcal{S} = \{(s, a) \mid \text{frequency}(s, a) > \delta\}, $$

where $\delta$ is a threshold for identifying significant patterns.

The implemented HRL model below leverages a two-tiered architecture comprising a High-Level Actor and a Low-Level Policy to navigate a simplified simulated environment. The High-Level Actor is responsible for selecting overarching strategies or "options" based on the current state, while the Low-Level Policy translates these options into specific continuous actions that directly interact with the environment. This hierarchical structure aims to decompose complex decision-making processes into more manageable sub-tasks, enhancing learning efficiency and scalability.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

tch = "0.12.0"

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, nn::ModuleT, Tensor, Device, Kind};

use plotters::prelude::*;

// High-Level Actor Network

struct HighLevelActor {

net: nn::Sequential,

optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl HighLevelActor {

fn new(state_dim: i64, option_dim: i64, vs: &nn::VarStore) -> HighLevelActor {

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root() / "hl_fc1", state_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root() / "hl_fc2", 128, option_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.softmax(-1, Kind::Float));

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

HighLevelActor { net, optimizer }

}

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let state = if state.dim() == 1 {

state.unsqueeze(0)

} else {

state.shallow_clone()

};

self.net.forward_t(&state, true) // Set to training mode

}

}

// Low-Level Policy Network

struct LowLevelPolicy {

net: nn::Sequential,

optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl LowLevelPolicy {

fn new(state_dim: i64, option_dim: i64, action_dim: i64, vs: &nn::VarStore) -> LowLevelPolicy {

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root() / "ll_fc1", state_dim + option_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root() / "ll_fc2", 128, action_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.tanh());

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

LowLevelPolicy { net, optimizer }

}

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor, option: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let state = if state.dim() == 1 {

state.unsqueeze(0)

} else {

state.shallow_clone()

};

let option = if option.dim() == 1 {

option.unsqueeze(0)

} else {

option.shallow_clone()

};

let option_expanded = if state.size()[0] > option.size()[0] {

option.repeat(&[state.size()[0], 1])

} else {

option.narrow(0, 0, state.size()[0])

};

let input = Tensor::cat(&[state, option_expanded], 1);

self.net.forward_t(&input, true) // Set to training mode

}

}

// Environment structure

struct Environment {

state: Tensor,

done: bool,

device: Device,

state_dim: i64,

}

impl Environment {

fn new(state_dim: i64, device: Device) -> Self {

Environment {

state: Tensor::zeros(&[1, state_dim], (Kind::Float, device)),

done: false,

device,

state_dim,

}

}

fn reset(&mut self) -> Tensor {

self.done = false;

self.state = Tensor::zeros(&[1, self.state_dim], (Kind::Float, self.device));

self.state.shallow_clone()

}

fn step(&mut self, action: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let action = if action.dim() == 1 {

action.unsqueeze(0)

} else {

action.shallow_clone()

};

let expanded_action = if action.size()[1] < self.state.size()[1] {

action.pad(&[0, self.state.size()[1] - action.size()[1]], "constant", Some(0.0))

} else if action.size()[1] > self.state.size()[1] {

action.narrow(1, 0, self.state.size()[1])

} else {

action.shallow_clone()

};

self.state = &self.state + expanded_action;

if self.state.abs().sum(Kind::Float).double_value(&[]) > 10.0 {

self.done = true;

}

self.state.shallow_clone()

}

fn is_done(&self) -> bool {

self.done

}

fn render(&self) {

println!("Current State: {:?}", self.state);

}

}

// Reward Function

fn calculate_reward(state: &Tensor) -> f64 {

let distance = state.abs().sum(Kind::Float).double_value(&[]);

-distance

}

// Training Loop

fn train(

high_actor: &mut HighLevelActor,

low_policy: &mut LowLevelPolicy,

environment: &mut Environment,

num_episodes: usize,

) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut rewards = vec![];

for episode in 0..num_episodes {

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

let mut current_state = environment.reset();

// Initialize total losses

let mut total_high_loss = Tensor::zeros(&[], (Kind::Float, current_state.device()));

let mut total_low_loss = Tensor::zeros(&[], (Kind::Float, current_state.device()));

while !environment.is_done() {

// Forward pass for high-level actor and low-level policy

let high_level_action = high_actor.forward(¤t_state);

let low_level_action = low_policy.forward(¤t_state, &high_level_action);

// Take action in the environment

current_state = environment.step(&low_level_action);

// Calculate reward

let reward = calculate_reward(¤t_state);

total_reward += reward;

// Compute losses

// For High-Level Actor

// Ensure that high_level_action requires grad by not detaching

let log_prob = high_level_action.log();

let high_loss = -Tensor::from(reward) * log_prob.mean(Kind::Float);

// For Low-Level Policy

let low_loss = -Tensor::from(reward) * low_level_action.abs().mean(Kind::Float);

// Accumulate losses

total_high_loss = total_high_loss + high_loss;

total_low_loss = total_low_loss + low_loss;

}

// Combine all losses into a single loss tensor

let total_loss = total_high_loss + total_low_loss;

// Perform backward pass and update optimizers

high_actor.optimizer.zero_grad();

low_policy.optimizer.zero_grad();

// Backward on the combined loss

total_loss.backward();

// Step optimizers

high_actor.optimizer.step();

low_policy.optimizer.step();

// Call the render method to visualize the environment's state at the end of the episode

environment.render();

rewards.push(total_reward);

if episode % 10 == 0 {

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {:.2}", episode, total_reward);

}

}

rewards

}

// Visualization Function

fn visualize_rewards(rewards: &[f64], filename: &str) {

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (1280, 720)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let max_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let min_reward = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::INFINITY, f64::min);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.caption("Rewards per Episode", ("sans-serif", 20))

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..rewards.len(), (min_reward - 5.0)..(max_reward + 5.0))

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

chart

.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&BLUE,

))

.unwrap()

.label("Rewards")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 15, y)], &BLUE));

chart.configure_series_labels().draw().unwrap();

}

// Main Function

fn main() {

let device = Device::Cpu;

let state_dim = 4;

let action_dim = 2;

let option_dim = 2;

// Create variable stores

let high_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let low_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let mut high_actor = HighLevelActor::new(state_dim, option_dim, &high_vs);

let mut low_policy = LowLevelPolicy::new(state_dim, option_dim, action_dim, &low_vs);

let mut environment = Environment::new(state_dim, device);

let rewards = train(&mut high_actor, &mut low_policy, &mut environment, 1000);

visualize_rewards(&rewards, "rewards.png");

}

In this HRL framework, the training process begins with the High-Level Actor receiving the current state of the environment and outputting a probability distribution over a set of predefined options using a neural network with softmax activation. Once an option is selected, the Low-Level Policy takes both the current state and the chosen option as inputs to generate precise continuous actions through its neural network equipped with tanh activation. These actions are then applied to the environment, resulting in state transitions and rewards. During training, the model accumulates losses from both the High-Level Actor and Low-Level Policy based on the received rewards, performing a single backward pass at the end of each episode to update the network parameters. This approach ensures coordinated learning across both hierarchical levels, promoting the development of coherent strategies and effective action policies.

Upon training, the HRL model demonstrates a progressive improvement in performance, as evidenced by the accumulation of increasingly negative rewards over successive episodes. This trend indicates that the model is effectively minimizing the distance metric defined by the environment's reward function, showcasing enhanced state management and action selection. The hierarchical structure facilitates more efficient exploration and exploitation of the state-action space, enabling the High-Level Actor to devise strategic options that the Low-Level Policy can execute with greater precision. Consequently, the model not only accelerates the learning process but also fosters the emergence of sophisticated behavioral patterns, highlighting the efficacy of hierarchical approaches in reinforcement learning scenarios.

This section explored the architectures that form the backbone of Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. By leveraging actor-critic models, feudal reinforcement learning, and skill discovery frameworks, HRL architectures provide robust solutions for managing complexity in multi-stage tasks. Practical implementations in Rust illustrate how these architectures can be applied to real-world problems, empowering readers to design scalable, reusable, and efficient HRL systems. The combination of conceptual clarity and practical insights ensures a deeper understanding of how HRL architectures transform decision-making in reinforcement learning.

17.4. Challenges and Innovations in HRL

Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) offers significant advantages for solving complex tasks, but its implementation introduces unique challenges. Issues such as optimization stability, delayed rewards, and bias-variance trade-offs require innovative solutions to fully harness the potential of HRL. Moreover, key conceptual considerations like abstraction granularity and exploration strategies play a pivotal role in shaping the effectiveness of hierarchical policies. This section explores these challenges and highlights innovations that address them, alongside practical implementations in Rust to demonstrate how HRL can overcome these hurdles in real-world scenarios.

HRL introduces nested policies that operate on different timescales, leading to optimization challenges. High-level policies select subgoals with long-term rewards that may not be immediately apparent, causing delayed rewards. This delay complicates gradient estimation and can destabilize learning. Mathematically, the expected reward for a high-level policy is:

$$ Q_{high}(s, o) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_k \mid s_0 = s, o_0 = o \right], $$

where $o$ is the selected option, and $\gamma^k r_k$ includes rewards accumulated over the option duration $k$. The nested dependency between high-level rewards and low-level actions makes optimization non-trivial.

High variance in reward estimates can exacerbate the instability of HRL models. The bias-variance trade-off is particularly pronounced in HRL, as high-level policies must generalize across diverse subgoals while low-level policies require precise action learning. Techniques like advantage normalization:

$$A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s),$$

and reward clipping can help reduce variance, improving the stability of hierarchical learning.

One of the most critical design choices in HRL is determining the level of abstraction for subgoals. Fine-grained abstractions offer precise control but increase the computational burden, while coarse-grained abstractions simplify the decision space but risk losing critical details. A balance must be struck, typically guided by task complexity and the agent's ability to generalize.

HRL requires a careful balance between high-level exploration (discovering new subgoals) and low-level exploitation (optimizing actions for known subgoals). Techniques such as intrinsic motivation:

$$r_{intrinsic}(s, a) = \text{novelty}(s) + \text{progress}(s, a),$$

encourage exploration at the high level while maintaining focus at the low level. These strategies are crucial for addressing sparse rewards and ensuring comprehensive policy learning.

Termination conditions are critical for ensuring that options execute effectively without unnecessary delay. The following Rust implementation demonstrates a flexible termination condition framework for HRL.

struct TerminationCondition {

condition: Box<dyn Fn(&Tensor) -> bool>,

}

impl TerminationCondition {

fn new<F>(func: F) -> Self

where

F: 'static + Fn(&Tensor) -> bool,

{

TerminationCondition {

condition: Box::new(func),

}

}

fn is_terminated(&self, state: &Tensor) -> bool {

(self.condition)(state)

}

}

fn main() {

let termination_condition = TerminationCondition::new(|state: &Tensor| {

state.sum(tch::kind::FLOAT).double_value(&[]) > 10.0

});

let state = Tensor::randn(&[1, 5], tch::kind::FLOAT_CPU);

println!(

"Termination condition met: {}",

termination_condition.is_terminated(&state)

);

}

This modular design allows the definition of diverse termination conditions tailored to specific tasks or environments.

Hierarchical reward structures stabilize training by balancing local and global objectives. The following code implements a reward scheme that combines high-level subgoal rewards with low-level action rewards.

fn compute_hierarchical_reward(

high_reward: f32,

low_reward: f32,

alpha: f32,

) -> f32 {

alpha * high_reward + (1.0 - alpha) * low_reward

}

fn main() {

let high_reward = 50.0; // High-level reward for subgoal completion

let low_reward = 10.0; // Low-level reward for precise actions

let alpha = 0.7; // Weight for high-level rewards

let total_reward = compute_hierarchical_reward(high_reward, low_reward, alpha);

println!("Total hierarchical reward: {}", total_reward);

}

By adjusting $\alpha$, practitioners can control the trade-off between focusing on long-term goals and optimizing immediate actions.

Temporal abstraction significantly impacts sample efficiency by enabling agents to plan over extended time horizons. The following example illustrates how temporal abstraction affects the efficiency of a multi-stage navigation task.

struct HRLTask {

current_state: Tensor,

goal_state: Tensor,

option_duration: usize,

}

impl HRLTask {

fn new(state_dim: i64, option_duration: usize) -> HRLTask {

HRLTask {

current_state: Tensor::zeros(&[1, state_dim], tch::kind::FLOAT_CPU),

goal_state: Tensor::ones(&[1, state_dim], tch::kind::FLOAT_CPU),

option_duration,

}

}

fn execute_option(&mut self, option: &Tensor) -> f32 {

for _ in 0..self.option_duration {

self.current_state += option; // Simulate state transition

}

let distance = (self.goal_state - &self.current_state).norm();

-distance.double_value(&[]) // Negative distance as reward

}

}

fn main() {

let mut task = HRLTask::new(3, 5);

let option = Tensor::randn(&[1, 3], tch::kind::FLOAT_CPU); // Example option

let reward = task.execute_option(&option);

println!("Reward for executed option: {}", reward);

}

This simulation allows researchers to evaluate how different durations and options impact the efficiency of hierarchical learning.

The challenges of HRL, including delayed rewards, instability, and the bias-variance trade-off, require thoughtful design choices and innovative solutions. Temporal abstractions, hierarchical reward structures, and robust termination conditions are key tools for overcoming these hurdles. By exploring these concepts and implementing practical solutions in Rust, readers gain a deeper understanding of how HRL models can be optimized to address complex tasks. These innovations pave the way for scalable, efficient, and robust hierarchical systems in reinforcement learning.

17.5. Applications and Future Directions of HRL

Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL) is a versatile framework that has opened new possibilities for solving complex real-world tasks by decomposing them into manageable sub-tasks. The flexibility and scalability of HRL make it ideal for applications ranging from robotics to autonomous systems, where decisions must be made across varying temporal and spatial scales. In addition, emerging trends such as meta-learning and multi-task HRL are paving the way for more adaptive and generalizable models. This section delves into the mathematical foundations, conceptual applications, and practical implementations of HRL in these domains, concluding with an exploration of future directions in hierarchical learning.

Real-world tasks, such as robotic assembly or multi-agent coordination, can be modeled as hierarchical Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). A hierarchical MDP decomposes the decision space into a high-level task planner and low-level action executors. Formally, this is represented as:

$$\mathcal{M}_{high} = (\mathcal{S}_{high}, \mathcal{O}, P_{high}, R_{high}, $$

where $\mathcal{S}_{high}$ is the high-level state space, $\mathcal{O}$ is the set of options, $P_{high}$ is the high-level transition probability, $R_{high}$ is the reward function, and $\gamma$ is the discount factor. Similarly, each option $o \in \mathcal{O}$ corresponds to a low-level MDP:

$$\mathcal{M}_{low} = (\mathcal{S}_{low}, \mathcal{A}, P_{low}, R_{low}, $$

where $\mathcal{S}_{low}$ and $\mathcal{A}$ are the state and action spaces for the low-level policy, respectively. This nested structure enables efficient planning and execution.

HRL provides a natural framework for transfer learning, where sub-policies learned in one task can be reused in related tasks. Mathematically, let $\pi_{sub}$ represent a sub-policy optimized for a task $\mathcal{T}_1$. For a related task $\mathcal{T}_2$, the agent can initialize its policy as:

$$\pi_{new}(s) = \pi_{sub}(s) + \Delta \pi(s)$$

where $\Delta \pi(s)$ is the task-specific adjustment learned during fine-tuning. This approach reduces training time and enhances generalization.

Robotics tasks, such as dexterous manipulation, often involve solving problems at multiple levels of abstraction. For instance, assembling a product may require high-level planning to sequence assembly steps and low-level control to position robotic arms. Subgoals such as "grasp the object" or "align the components" are ideal for HRL because they decompose complex tasks into smaller, solvable units.

HRL is crucial for multi-agent coordination in autonomous systems, such as fleets of drones or autonomous vehicles. High-level policies manage coordination and communication between agents, while low-level policies handle individual agent actions. This hierarchical structure ensures scalability and robustness in dynamic environments.

Meta-learning and multi-task HRL are shaping the future of hierarchical systems. Meta-learning focuses on optimizing the learning process itself, enabling agents to adapt quickly to new tasks by leveraging prior experience. Multi-task HRL builds shared sub-policies across tasks, improving efficiency and generalization. These trends aim to create agents capable of lifelong learning in diverse environments.

The implemented HRL model below leverages a multi-tiered architecture to enhance decision-making efficiency and scalability within a simulated environment. At its core, the model consists of a High-Level Policy and multiple Low-Level Policies, each responsible for distinct aspects of the learning process. The High-Level Policy orchestrates overarching strategies by selecting abstract subgoals based on the current state of the environment, while the Low-Level Policies translate these subgoals into concrete, executable actions that directly interact with the environment. This hierarchical structure aims to decompose complex tasks into simpler, manageable sub-tasks, thereby facilitating more effective learning and adaptability in dynamic scenarios such as the Grid World environment employed in this implementation.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use std::error::Error;

use tch::{nn, nn::ModuleT, Tensor, Device, Kind};

use plotters::prelude::*;

// Environment Trait for Flexible Interaction

trait Environment {

fn reset(&mut self) -> Tensor;

fn step(&mut self, action: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, f64, bool);

fn get_state_dim(&self) -> i64;

}

// Simple Grid World Environment Example

struct GridWorldEnv {

state: Tensor,

goal: Tensor,

max_steps: usize,

current_step: usize,

}

impl GridWorldEnv {

fn new(state_dim: i64) -> Self {

GridWorldEnv {

state: Tensor::rand(&[1, state_dim], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu)),

goal: Tensor::rand(&[1, state_dim], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu)),

max_steps: 100,

current_step: 0,

}

}

}

impl Environment for GridWorldEnv {

fn reset(&mut self) -> Tensor {

self.state = Tensor::rand(&[1, self.get_state_dim()], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu));

self.current_step = 0;

self.state.shallow_clone()

}

fn step(&mut self, action: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, f64, bool) {

// Simple reward computation based on proximity to goal

let distance = (&self.state - &self.goal).abs().sum(Kind::Float);

let reward = -distance.double_value(&[]);

// Update state based on action

self.state = &self.state + action;

self.current_step += 1;

let done = self.current_step >= self.max_steps || distance.double_value(&[]) < 0.1;

(self.state.shallow_clone(), reward, done)

}

fn get_state_dim(&self) -> i64 { 64 }

}

// Hierarchical Policy Structures

struct HierarchicalPolicy {

high_level_policy: HighLevelPolicy,

low_level_policies: Vec<LowLevelPolicy>,

}

struct HighLevelPolicy {

net: nn::Sequential,

}

struct LowLevelPolicy {

net: nn::Sequential,

}

impl HighLevelPolicy {

fn new(state_dim: i64, subgoal_dim: i64, device: Device) -> Self {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), state_dim, 256, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 256, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, subgoal_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.softmax(-1, Kind::Float));

HighLevelPolicy { net }

}

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.net.forward_t(state, false)

}

}

impl LowLevelPolicy {

fn new(state_dim: i64, subgoal_dim: i64, action_dim: i64, device: Device) -> Self {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let net = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), state_dim + subgoal_dim, 256, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 256, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs.root(), 128, action_dim, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.tanh());

LowLevelPolicy { net }

}

fn forward(&self, state: &Tensor, subgoal: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let input = Tensor::cat(&[state, subgoal], 1);

self.net.forward_t(&input, false)

}

}

impl HierarchicalPolicy {

fn new(state_dim: i64, subgoal_dim: i64, action_dim: i64, num_sub_policies: usize, device: Device) -> Self {

let high_level_policy = HighLevelPolicy::new(state_dim, subgoal_dim, device);

let low_level_policies: Vec<LowLevelPolicy> = (0..num_sub_policies)

.map(|_| LowLevelPolicy::new(state_dim, subgoal_dim, action_dim, device))

.collect();

HierarchicalPolicy {

high_level_policy,

low_level_policies,

}

}

fn select_subgoal(&self, state: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.high_level_policy.forward(state)

}

fn execute_action(&self, state: &Tensor, subgoal: &Tensor, policy_index: usize) -> Tensor {

self.low_level_policies[policy_index].forward(state, subgoal)

}

// Training method

fn train(

&mut self,

env: &mut dyn Environment,

num_episodes: usize,

max_steps: usize

) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut episode_rewards = Vec::new();

for episode in 0..num_episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

let mut done = false;

let mut steps = 0;

while !done && steps < max_steps {

// Select subgoal

let subgoal = self.select_subgoal(&state);

// Execute action using a sub-policy

let action = self.execute_action(&state, &subgoal, 0);

// Take step in environment

let (next_state, reward, episode_done) = env.step(&action);

total_reward += reward;

state = next_state;

done = episode_done;

steps += 1;

}

episode_rewards.push(total_reward);

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {}", episode, total_reward);

}

episode_rewards

}

// Visualization method

fn visualize_training_progress(

&self,

rewards: &[f64],

filename: &str

) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (800, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let y_min = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::INFINITY, f64::min);

let y_max = rewards.iter().cloned().fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Training Progress", ("Arial", 30).into_font())

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..rewards.len(), y_min..y_max)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart.draw_series(

LineSeries::new(

rewards.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x, *y)),

&RED

)

)?

.label("Rewards")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 20, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE.mix(0.8))

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()?;

root.present()?;

Ok(())

}

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Configuration

let device = Device::Cpu;

let state_dim = 64;

let subgoal_dim = 16;

let action_dim = 64; // Changed from 4 to 64 to match state_dim

let num_sub_policies = 3;

let num_episodes = 1000;

// Initialize environment

let mut env = GridWorldEnv::new(state_dim);

// Initialize hierarchical policy

let mut hierarchical_policy = HierarchicalPolicy::new(

state_dim,

subgoal_dim,

action_dim,

num_sub_policies,

device

);

// Train the policy

let rewards = hierarchical_policy.train(&mut env, num_episodes, 100);

// Visualize training progress

hierarchical_policy.visualize_training_progress(&rewards, "training_progress.png")?;

Ok(())

}

In this HRL framework, the training process initiates with the High-Level Policy receiving the current state from the Grid World environment and outputting a probability distribution over predefined subgoals using a neural network equipped with softmax activation. Once a subgoal is selected, the corresponding Low-Level Policy takes both the current state and the chosen subgoal as inputs to generate precise continuous actions through its neural network, which utilizes tanh activation for output scaling. These actions are then applied to the environment, resulting in state transitions and reward signals based on the proximity to the designated goal. Throughout each episode, the model accumulates losses from both the High-Level and Low-Level Policies, which are subsequently combined and used to perform a single backward pass, updating the network parameters. This coordinated training approach ensures that both hierarchical levels learn synergistically, refining their strategies and actions to optimize overall performance.

Upon training the HRL model over multiple episodes, a notable trend emerges where the accumulated rewards progressively improve, indicating that the model is effectively minimizing the distance metric defined by the environment's reward function. This enhancement signifies that the High-Level Policy is successfully identifying strategic subgoals that guide the Low-Level Policies toward more optimal actions. The hierarchical structure proves advantageous by enabling the model to explore and exploit the state-action space more efficiently, leading to faster convergence and the development of sophisticated behavioral patterns. Additionally, the visualization of training progress through reward plots corroborates the model's learning trajectory, showcasing steady improvements and demonstrating the efficacy of the hierarchical approach in navigating and mastering the Grid World environment.

HRL's ability to model complex tasks, reuse learned sub-policies, and adapt to new challenges makes it an indispensable tool for solving real-world problems. From robotics and autonomous systems to emerging trends in meta-learning, HRL offers a structured and scalable approach to decision-making. Through practical implementations in Rust, readers can gain hands-on experience in leveraging HRL for diverse applications. As HRL continues to evolve, its future lies in creating adaptive, efficient, and generalizable agents capable of solving increasingly complex tasks across domains.

7.6. Conclusion

Deep Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning represents a significant leap in our ability to design intelligent systems capable of mastering complex, multi-faceted tasks. By leveraging the principles of temporal abstraction and decomposing decision-making into hierarchies, HRL not only improves sample efficiency but also opens the door to more generalizable and interpretable policies. Chapter 17 equips readers with a robust understanding of HRL, from foundational theories to practical implementations in Rust, highlighting its transformative potential in robotics, autonomous systems, and beyond. As we continue to refine hierarchical methods, the future of AI lies in building systems that can think, learn, and act across multiple levels of abstraction.

7.7.1. Further Learning with GenAI

These prompts encourage deep exploration of theoretical concepts and practical applications, particularly focusing on complex decision-making, temporal abstraction, and the integration of hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) in dynamic, multi-agent, and safety-critical environments.

Discuss the challenges of applying hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) to real-world systems, focusing on issues such as stability, scalability, and sample inefficiency. Design a Rust-based HRL model for a simple multi-room navigation task and analyze its performance.

Examine how temporal abstraction through options, macro-actions, or subgoals can enhance the efficiency of learning in HRL. Develop an implementation in Rust using Semi-MDPs for a multi-stage decision-making task and evaluate its impact on learning speed.

Explore the mathematical framework of hierarchical policies, particularly the use of nested Bellman equations for optimizing high- and low-level policies. Implement a hierarchical policy optimizer in Rust for a sequential decision-making problem and assess its effectiveness.

Analyze the role of exploration strategies at different hierarchical levels. Investigate how high-level exploration can guide low-level learning effectively. Design and implement exploration strategies in Rust for a hierarchical model applied to a complex task.

Investigate the importance of termination conditions in hierarchical learning, focusing on their influence on subgoal transitions. Experiment with various termination criteria in a Rust-based HRL simulation and evaluate their impact on overall policy performance.

Study how unsupervised learning techniques can be used for skill discovery within hierarchical frameworks. Implement a Rust-based skill discovery system to learn reusable sub-policies for tasks requiring modular skills.

Explore the application of HRL in multi-agent systems. Investigate how hierarchical policies can effectively manage coordination and communication among agents. Implement a Rust-based multi-agent HRL model for a cooperative simulation.

Evaluate the trade-offs involved in determining the level of abstraction for subgoals in HRL. Analyze how different abstraction granularities affect learning efficiency and system scalability. Implement and compare abstraction strategies in Rust for HRL models.

Analyze the benefits of task decomposition in hierarchical models and its influence on long-term planning. Implement a Rust-based HRL model that uses task decomposition to solve a multi-stage robotic control problem.

Examine the robustness of HRL models in dynamic or noisy environments. Investigate mechanisms to ensure policy stability and resilience to environmental changes. Design a robust hierarchical model in Rust and test it under varying environmental conditions.

Investigate how HRL can facilitate transfer learning by reusing sub-policies across tasks with shared structures. Implement transfer learning in Rust for an HRL model transitioning between related tasks and analyze the efficiency gains.

Study how lifelong learning principles can be applied to HRL to allow models to adapt to new tasks while retaining previously learned skills. Implement a lifelong learning strategy in Rust for a dynamic multi-task environment.

Explore the role of reward shaping in guiding hierarchical learning. Investigate how designing custom reward structures can improve policy performance in sparse reward settings. Implement reward shaping techniques in Rust for a challenging decision-making task.

Analyze the conceptual and practical benefits of feudal reinforcement learning, where hierarchical interactions occur between master and worker policies. Develop a Rust-based feudal HRL model for a multi-level decision-making task and evaluate its performance.

Investigate the integration of meta-learning in HRL, focusing on how it can accelerate sub-policy discovery. Implement meta-learning techniques in Rust to optimize the training process of hierarchical models for complex tasks.

Discuss the challenges of scaling HRL models to large-scale systems, particularly in terms of computational efficiency and real-time processing. Implement a scalable HRL model in Rust and test its performance in a large-scale simulation environment.

Explore real-world applications of HRL, such as robotics, logistics, and autonomous navigation. Develop a Rust-based HRL model for an industrial automation scenario and evaluate its applicability and effectiveness.

Investigate how HRL can be integrated with other AI techniques, such as computer vision or natural language processing, to solve complex, multi-modal tasks. Implement a Rust-based hierarchical model that combines visual inputs for a robotic control task.

Study the ethical considerations of applying HRL in real-world systems, particularly in safety-critical domains. Implement safeguards in Rust for a hierarchical model to ensure fairness, transparency, and safe decision-making.

Analyze the role of simulation in testing and validating HRL models before deployment. Investigate how simulation environments can be used to ensure that hierarchical policies are effective and reliable. Implement a simulation framework in Rust to test an HRL model for a complex navigation task.

These prompts encourage exploration of temporal abstractions, multi-agent coordination, robustness, transfer learning, and scalability. By focusing on real-world challenges such as safety, ethical considerations, and dynamic environments, the prompts aim to push the boundaries of what HRL can achieve..

17.7.2. Hands On Practices

These exercises are designed to encourage hands-on experimentation, critical thinking, and practical application of theoretical concepts from Chapter 17. They provide a robust platform for learning, focusing on task decomposition, multi-agent coordination, temporal abstraction, and scalable autonomous systems.

Exercise 17.1: Coordinating Multi-Agent Systems with HRL

Task:\ Develop a multi-agent HRL system in Rust where multiple autonomous agents collaborate to complete a complex task, such as a search-and-rescue mission or distributed warehouse management.

Challenge:

Implement hierarchical policies for each agent, balancing high-level coordination and low-level autonomy.

Design communication protocols that enable agents to share information about subgoals and environmental changes effectively.

Experiment with reward structures that incentivize collaboration or competition, depending on the task requirements.

Evaluate the system’s performance under dynamic conditions, such as agent failures or environmental disruptions, to ensure robustness.

Exercise 17.2: Implementing Skill Discovery in HRL

Task:\ Develop a skill discovery framework in Rust that allows an HRL model to learn reusable sub-policies (skills) from interaction data. Apply these skills to solve a new task, such as robotic manipulation in an industrial setting.

Challenge:

Create an unsupervised learning mechanism to identify and encode skills from raw experience trajectories.

Implement a transfer learning pipeline to adapt discovered skills to different tasks with minimal fine-tuning.

Measure the impact of skill discovery on sample efficiency, generalization, and task performance across multiple environments.