Chapter 18

Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

"The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination." — Albert Einstein

Chapter 18 delves into the sophisticated realm of Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL), extending the foundational principles of single-agent reinforcement learning to environments populated by multiple interacting agents. This chapter meticulously explores the mathematical frameworks underpinning MADRL, including multi-agent Markov Decision Processes and equilibrium concepts from game theory. It examines core algorithms tailored for multi-agent scenarios, such as Independent Q-Learning, MADDPG, and Actor-Critic methods, highlighting their theoretical foundations and practical implementations. A significant focus is placed on communication and coordination mechanisms that enable agents to collaborate or compete effectively, fostering emergent behaviors that arise from their interactions. Leveraging Rust's powerful concurrency and performance-oriented features, the chapter provides hands-on examples and case studies that illustrate the implementation of MADRL algorithms in real-world applications. By integrating rigorous theoretical insights with practical coding strategies, Chapter 18 equips readers with the knowledge and skills to design, implement, and evaluate sophisticated multi-agent reinforcement learning systems using Rust.

18.1. Introduction to Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning

As reinforcement learning (RL) continues to revolutionize various domains, the extension to multi-agent systems—known as Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL)—presents a frontier of both immense potential and intricate challenges. This section offers a thorough introduction of MADRL, encompassing its foundational definitions, mathematical frameworks, key conceptual insights, and practical implementation strategies using Rust. By integrating advanced theoretical concepts with hands-on programming, this chapter aims to equip you with the necessary tools to design and develop sophisticated multi-agent systems.

Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) represents the confluence of reinforcement learning and multi-agent systems, where multiple autonomous agents interact within a shared environment. Unlike single-agent RL, where an individual agent learns to maximize its own cumulative reward, MADRL involves multiple agents that may have cooperative, competitive, or mixed objectives. This interaction introduces a layer of complexity, as the environment's dynamics are influenced by the policies of all participating agents.

Figure 1: The natural evolution and progress of MADRL.

The origins of MADRL can be traced back to the foundational work in both multi-agent systems (MAS) and reinforcement learning. Early studies in MAS, such as game theory in the mid-20th century, provided the theoretical backbone for analyzing interactions among multiple decision-makers. Concepts like Nash Equilibrium, developed by John Nash in the 1950s, laid the groundwork for understanding stable strategies in competitive environments. These ideas were later extended to dynamic and stochastic settings, giving rise to tools like Markov games and stochastic games, which remain central to MADRL today.

Simultaneously, the evolution of reinforcement learning through the 1980s and 1990s saw the development of algorithms like Q-learning and Temporal Difference (TD) learning, which allowed single agents to learn optimal policies through trial-and-error interactions with an environment. However, applying these methods to multi-agent systems proved challenging due to the non-stationarity introduced by other learning agents. This realization prompted early research into multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), where algorithms were adapted to account for the changing dynamics caused by interacting agents.

The advent of deep learning in the 2010s marked a turning point for MADRL. Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and other neural-network-based approaches revolutionized RL by enabling agents to learn directly from high-dimensional inputs such as images. Researchers began extending these methods to multi-agent settings, resulting in algorithms like Deep Deterministic Policy Gradients (DDPG) for continuous action spaces and its multi-agent counterpart, MADDPG, which facilitated coordinated learning among agents. Concurrently, advancements in hardware, such as GPUs and TPUs, allowed researchers to scale MADRL experiments to environments with dozens or even hundreds of agents.

In recent years, MADRL has gained prominence in diverse applications ranging from autonomous driving and robotics to smart grid management and multi-robot collaboration. Frameworks like centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) have emerged to balance the need for coordination during training with the independence of agents during execution. Research has also explored specialized architectures, such as attention mechanisms for inter-agent communication and graph neural networks for structured agent interactions, further enriching the capabilities of MADRL.

Today, MADRL stands at the confluence of game theory, RL, and deep learning, offering a rich field of research and practical innovation. The challenges of scalability, non-stationarity, and coordination continue to drive advancements, as do the demands of real-world applications that require robust and adaptive multi-agent solutions. This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of these developments, enabling you to navigate the complexities of MADRL with both theoretical and practical proficiency.

Formally, MADRL can be viewed as an extension of single-agent RL frameworks, incorporating multiple decision-makers whose actions collectively determine the state transitions and reward distributions. Each agent maintains its own policy, which it adapts based on its experiences and observations, often necessitating decentralized learning mechanisms or centralized training approaches to handle the interdependencies among agents.

Mathematically, MADRL builds upon the concept of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), generalizing them to accommodate multiple agents. This extension not only increases the dimensionality of the state and action spaces but also introduces strategic interactions that require agents to anticipate and respond to the behaviors of others.

At the heart of MADRL lies the Multi-Agent Markov Decision Process (MMDP), a comprehensive framework that generalizes single-agent MDPs to multi-agent scenarios. An MMDP is defined by the tuple $\langle S, \{A_i\}, P, \{R_i\}, \gamma \rangle$, where:

$S$ is the finite set of states representing all possible configurations of the environment.

$\{A_i\}$ is a collection of action sets, with $A_i$ representing the actions available to agent $i$.

$P: S \times A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_N \times S \rightarrow [0,1]$ denotes the state transition probability function, which defines the probability of transitioning to a new state $s'$ given the current state $s$ and the actions $a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N$ taken by each agent.

$\{R_i\}$ is a set of reward functions, where $R_i: S \times A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_N \times S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ specifies the reward received by agent $i$ after transitioning from state $s$ to state $s'$ due to the joint action $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N)$.

$\gamma$ is the discount factor, $0 \leq \gamma < 1$, which determines the importance of future rewards.

In scenarios where agents have conflicting objectives, the framework extends to Markov Games or Stochastic Games, where each agent's reward function can depend not only on the state and its own action but also on the actions of other agents. This setup necessitates the consideration of equilibrium concepts, such as Nash Equilibrium, where no agent can unilaterally improve its expected reward by deviating from its current policy.

To encapsulate the strategic interactions among agents, the concept of policies becomes more nuanced. Each agent $i$ adopts a policy $\pi_i: S \rightarrow A_i$, mapping states to actions. The joint policy $\boldsymbol{\pi} = (\pi_1, \pi_2, \dots, \pi_N)$ governs the collective behavior of all agents within the environment. The goal for each agent is to find an optimal policy $\pi_i^*$ that maximizes its expected cumulative reward, considering the policies of other agents.

A robust understanding of Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) requires a clear grasp of several foundational concepts, each adapted to the multi-agent context. Agents are the autonomous decision-makers, capable of perceiving the environment, selecting actions, and pursuing specific objectives, either independently or collaboratively. States capture the dynamic configuration of the environment at any given moment, often encompassing detailed information about all agents, such as their positions and observations. Actions are the decisions or moves available to agents, directly impacting state transitions and shaping the trajectory of rewards. Rewards serve as feedback signals, evaluating the outcomes of actions in specific states; they may be individual or shared, reflecting the cooperative or competitive nature of agent interactions. Policies guide agents' decision-making processes, mapping states to actions through strategies that can be deterministic or stochastic, often parameterized by advanced models like neural networks. Finally, the environment serves as the shared operational space, defining the rules, dynamics, and interactions that govern agent behavior and learning. Together, these elements form the foundation of MADRL, enabling complex, coordinated learning in decentralized systems.

The significance of MADRL extends across a multitude of real-world applications where multiple autonomous agents must operate concurrently and interact dynamically. Consider autonomous driving systems, where each vehicle (agent) must navigate shared roadways while anticipating the actions of other vehicles to ensure safety and efficiency. In robotics, multiple robots might collaborate to perform complex tasks such as search and rescue missions, where coordination and communication are paramount.

Distributed systems, such as smart grids or decentralized networks, rely on MADRL to optimize performance amidst varying objectives and constraints. In such settings, agents must adapt to changing conditions, manage resources effectively, and maintain robust communication channels. Moreover, MADRL finds applications in economic models, where agents represent individual entities like consumers or firms, each striving to maximize their utility within a competitive marketplace.

The ability of MADRL to model and solve problems involving strategic interactions among agents makes it an indispensable tool in advancing technologies that require high levels of autonomy, coordination, and adaptability.

Interactions among agents in MADRL can be broadly classified into cooperative, competitive, and mixed scenarios, each characterized by distinct dynamics and objectives.

Cooperative Interactions: In purely cooperative settings, agents work collaboratively towards a common goal, often sharing information and rewards. The reward functions are typically aligned, encouraging agents to coordinate their actions to maximize the collective reward. Mathematically, if all agents share a common reward function RRR, each agent iii seeks to maximize the expected cumulative reward $\mathbb{E}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R(s_t, \mathbf{a}_t) \right]$, where $\mathbf{a}_t = (a_1^t, a_2^t, \dots, a_N^t)$ represents the joint actions of all agents at time $t$.

Competitive Interactions: In competitive environments, agents have opposing objectives, akin to players in a zero-sum game. The reward of one agent is typically the negative of another's, creating a scenario where the gain of one agent corresponds to the loss of another. Formally, if agent 1 aims to maximize $R_1$, agent 2 may seek to minimize $R_1$, leading to a saddle-point equilibrium,$\max_{\pi_1} \min_{\pi_2} \mathbb{E}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_1(s_t, \mathbf{a}_t) \right]$.

This dynamic necessitates agents to anticipate and counteract the strategies of their adversaries, often employing game-theoretic approaches to identify optimal policies.

Mixed Interactions: Many real-world scenarios involve mixed interactions, where agents exhibit both cooperative and competitive behaviors. For example, in team-based competitions, agents may collaborate within their teams while competing against opposing teams. The reward structure in such environments typically includes both shared and individual components, requiring agents to balance collective objectives with personal incentives. This duality introduces additional complexity in policy optimization, as agents must navigate the trade-offs between cooperation and competition. Mathematically, the reward functions in mixed interactions can be represented as $R_i = R_{\text{shared}} + R_{i,\text{individual}}$, where $R_{\text{shared}}$ pertains to the common objectives, and $R_{i,\text{individual}}$ captures the unique goals of agent $i$.

Developing effective MADRL systems involves addressing a myriad of challenges that arise from the inherently complex nature of multi-agent interactions:

Non-Stationarity: From the perspective of any single agent, the environment becomes non-stationary because other agents are simultaneously learning and adapting their policies. This dynamic shift complicates the learning process, as the optimal policy for an agent may continuously evolve in response to the changing strategies of others. Traditional RL algorithms, which assume a stationary environment, may struggle to converge in such settings. Addressing non-stationarity often involves incorporating mechanisms for agents to predict or adapt to the policies of their counterparts, such as opponent modeling or utilizing experience replay buffers that account for policy changes.

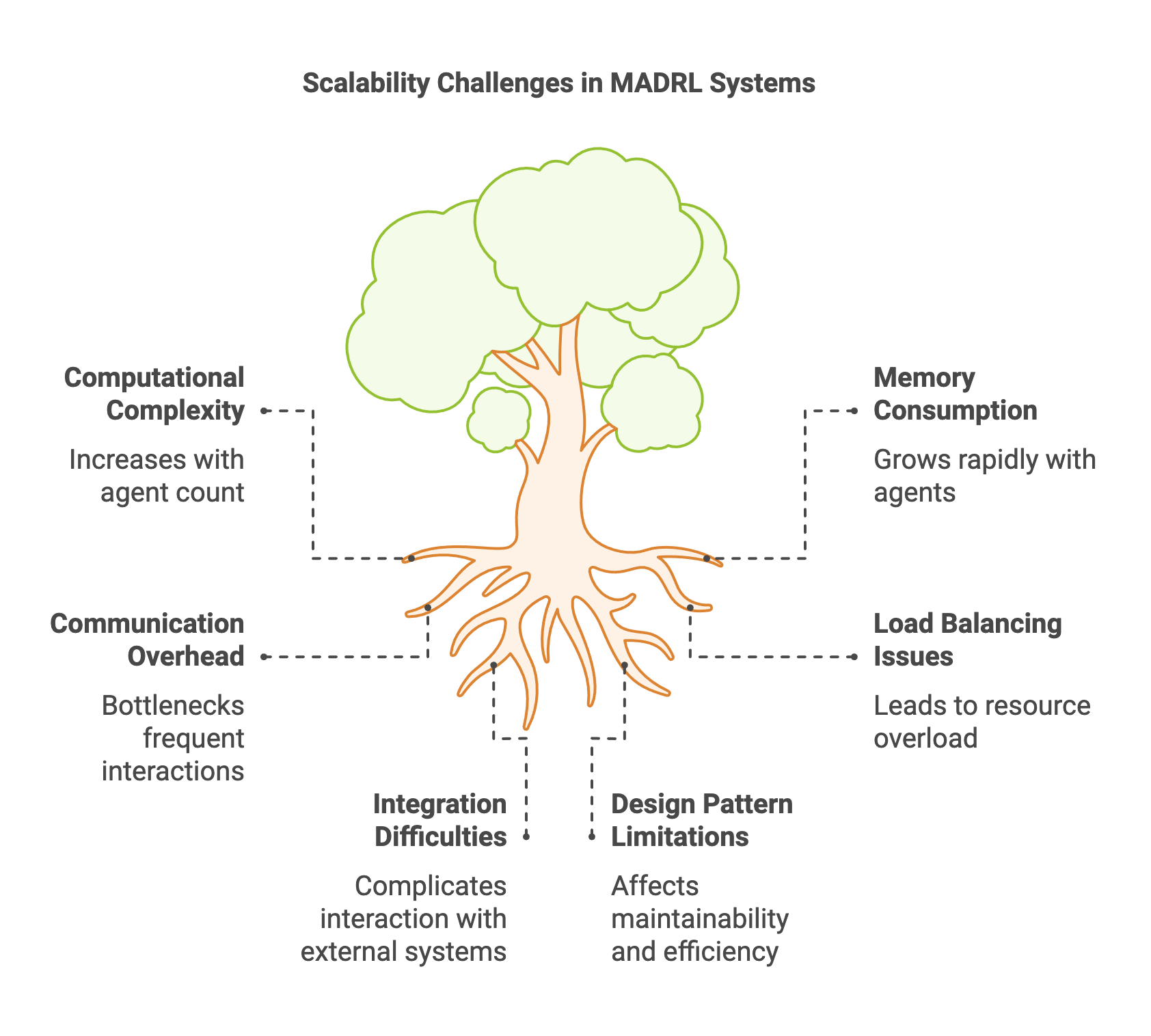

Scalability: The state and action spaces in MADRL scale exponentially with the number of agents, leading to the curse of dimensionality. As the number of agents increases, the computational resources required to process joint actions and state transitions grow rapidly, making it challenging to learn optimal policies efficiently. Strategies to mitigate scalability issues include factorizing the joint policy into individual policies, leveraging parameter sharing among agents, and employing decentralized learning approaches where each agent learns independently based on local observations.

Credit Assignment: In cooperative settings, where rewards are often shared among agents, determining the contribution of each agent to the overall performance becomes a critical issue. Proper credit assignment ensures that each agent receives appropriate feedback for its actions, facilitating effective policy updates. Techniques such as difference rewards, shaped rewards, or using centralized value functions with decentralized policies can help in accurately attributing rewards to individual agents.

Communication and Coordination: Effective communication is essential for coordination among agents, especially in cooperative or mixed settings. Designing communication protocols that are efficient, scalable, and robust to noise or failures is a significant challenge. Additionally, ensuring that agents can interpret and act upon communicated information in a meaningful way requires sophisticated mechanisms for encoding and decoding messages.

Equilibrium and Stability: Achieving stable equilibria, such as Nash Equilibria, where no agent can unilaterally improve its performance, is another complex aspect of MADRL. Ensuring convergence to such equilibria requires careful design of learning algorithms that account for the strategic interactions among agents. Techniques from game theory, such as best-response dynamics or regret minimization, are often employed to guide agents towards equilibrium states.

Addressing these challenges necessitates the development of advanced algorithmic strategies, including but not limited to centralized training with decentralized execution, hierarchical learning architectures, and the integration of game-theoretic principles. By navigating these obstacles, MADRL systems can achieve robust performance in complex, multi-agent environments.

Implementing MADRL in Rust leverages the language's strengths in performance, safety, and concurrency, making it an excellent choice for developing scalable and efficient multi-agent systems. Key Rust crates that facilitate MADRL implementation include tch-rs for tensor operations and neural network integration, petgraph for managing agent interactions through graph structures, and rand for stochastic processes essential in reinforcement learning.

To illustrate the principles of MADRL, let's develop a basic Rust program that initializes multiple agents and simulates their interactions within a shared environment. In this implementation, a MADRL framework is used, where agents operate within a graph-based environment. Each agent is equipped with a Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based policy model to process observations and determine optimal actions. The GNN policy enables agents to leverage graph-based information, including their local state and their neighbors' proximity, to make decisions. Agents interact with the environment and adapt their strategies over time based on rewards, which are computed based on their positions in the grid.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

petgraph = "0.6.5"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use petgraph::graph::{Graph, NodeIndex};

use petgraph::Undirected;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::Rng;

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

#[derive(Clone)]

// Configuration for the environment

struct EnvironmentConfig {

num_agents: usize, // Number of agents in the environment

grid_size: f32, // Size of the 2D grid

communication_radius: f32, // Communication radius for graph edges

}

// Neural network policy for agents using a GNN-based architecture

struct GNNPolicy {

_vs: nn::VarStore, // Variable store for model parameters

graph_embedding: nn::Linear, // Embedding layer for graph data

policy_network: nn::Linear, // Network for policy generation

optimizer: nn::Optimizer, // Optimizer for training the policy

}

impl GNNPolicy {

// Creates a new GNN policy with specified input, hidden, and output dimensions

fn new(input_dim: i64, hidden_dim: i64, output_dim: i64) -> Result<Self, tch::TchError> {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let root = vs.root();

// Define the embedding layer for graph input

let graph_embedding = nn::linear(

root.clone() / "graph_embedding",

input_dim,

hidden_dim,

Default::default(),

);

// Define the policy network for generating actions

let policy_network = nn::linear(

root.clone() / "policy_network",

hidden_dim,

output_dim,

Default::default(),

);

// Set up an Adam optimizer

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3)?;

Ok(Self {

_vs: vs,

graph_embedding,

policy_network,

optimizer,

})

}

// Forward pass through the GNN policy

fn forward(&self, input: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let embedded = self.graph_embedding.forward(input);

let action_logits = self.policy_network.forward(&embedded);

action_logits

}

// Updates the policy using the given state, action, and reward

fn update(&mut self, state: &Tensor, action: &Tensor, reward: &Tensor) -> f64 {

let action = action.view([-1, 1]); // Ensure action tensor has the correct shape

let loss = -self.forward(state)

.log_softmax(-1, Kind::Float) // Apply log-softmax for categorical actions

.gather(1, &action, false) // Select action probabilities

.f_mul(reward) // Multiply by the reward

.expect("Failed to multiply tensors")

.mean(Kind::Float); // Compute the mean loss

// Perform a backward pass and update the model parameters

self.optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

loss.double_value(&[]) // Return the loss as a scalar

}

}

// Represents an agent in the environment

struct Agent {

id: NodeIndex, // Unique identifier for the agent

position: (f32, f32), // Position of the agent in the 2D grid

policy: Option<GNNPolicy>, // GNN policy for decision-making

}

// Multi-agent environment with graph structure

struct Environment {

graph: Graph<Agent, (), Undirected>, // Undirected graph of agents

config: EnvironmentConfig, // Configuration of the environment

rewards: Vec<Vec<f64>>, // Rewards for each agent over time

losses: Vec<Vec<f64>>, // Losses for each agent over time

}

impl Environment {

// Initialize the environment with agents and connections

fn new(config: EnvironmentConfig) -> Result<Self, Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let mut graph = Graph::<Agent, (), Undirected>::new_undirected();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut agents = Vec::new();

// Create agents and add them to the graph

for _ in 0..config.num_agents {

let position = (

rng.gen_range(0.0..config.grid_size), // Random x-coordinate

rng.gen_range(0.0..config.grid_size), // Random y-coordinate

);

let policy = GNNPolicy::new(config.num_agents as i64, 64, 4)?;

let node_index = graph.add_node(Agent {

id: NodeIndex::new(graph.node_count()),

position,

policy: Some(policy),

});

agents.push(node_index);

}

// Create graph edges based on proximity

for i in 0..agents.len() {

for j in (i + 1)..agents.len() {

let node_i = &graph[agents[i]];

let node_j = &graph[agents[j]];

let dist = ((node_i.position.0 - node_j.position.0).powi(2)

+ (node_i.position.1 - node_j.position.1).powi(2))

.sqrt();

if dist <= config.communication_radius {

graph.add_edge(agents[i], agents[j], ());

}

}

}

Ok(Environment {

graph,

config: config.clone(),

rewards: vec![Vec::new(); config.num_agents],

losses: vec![Vec::new(); config.num_agents],

})

}

// Perform one step of simulation

fn step(&mut self, _step_number: usize) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Create a placeholder state tensor for agents

let state_tensor = Tensor::zeros(

&[self.config.num_agents as i64, self.config.num_agents as i64],

(Kind::Float, Device::Cpu),

);

// Update each agent based on its policy

for (index, node_index) in self.graph.node_indices().enumerate() {

let agent = &mut self.graph[node_index];

if let Some(policy) = agent.policy.as_mut() {

let action_tensor = Tensor::randint(4, &[1], (Kind::Int64, Device::Cpu)); // Random action

let reward = -agent.position.0.powi(2) - agent.position.1.powi(2); // Reward based on position

let reward_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&[reward]).to_device(Device::Cpu);

let loss = policy.update(&state_tensor, &action_tensor, &reward_tensor);

self.rewards[index].push(reward as f64); // Track rewards

self.losses[index].push(loss); // Track losses

// Update agent position based on action

match action_tensor.int64_value(&[]) {

0 => agent.position.0 += 0.1, // Move right

1 => agent.position.0 -= 0.1, // Move left

2 => agent.position.1 += 0.1, // Move up

3 => agent.position.1 -= 0.1, // Move down

_ => {}

}

// Bound the position within the grid

agent.position.0 = agent.position.0.max(0.0).min(self.config.grid_size);

agent.position.1 = agent.position.1.max(0.0).min(self.config.grid_size);

}

}

Ok(())

}

// Visualize rewards and losses over time

fn visualize(&self) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("output/agents_rewards_and_losses.png", (800, 600))

.into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Agents Rewards and Losses Over Time", ("sans-serif", 20))

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..200, -100.0..10.0)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

for (agent_idx, (reward_series, loss_series)) in self.rewards.iter().zip(&self.losses).enumerate() {

let agent_color = Palette99::pick(agent_idx).to_rgba(); // Assign a unique color

chart.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

reward_series.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x as i32, *y)),

&agent_color,

))?

.label(format!("Agent {} Reward", agent_idx))

.legend(move |(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 10, y)], &agent_color));

chart.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

loss_series.iter().enumerate().map(|(x, y)| (x as i32, *y)),

&agent_color.mix(0.5),

))?

.label(format!("Agent {} Loss", agent_idx))

.legend(move |(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 10, y)], &agent_color.mix(0.5)));

}

chart.configure_series_labels()

.background_style(&WHITE.mix(0.8))

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()?;

println!("Visualization saved to output/agents_rewards_and_losses.png");

Ok(())

}

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let config = EnvironmentConfig {

num_agents: 5,

grid_size: 10.0,

communication_radius: 2.0,

};

let mut env = Environment::new(config)?;

for step in 0..200 {

println!("Step {}", step);

env.step(step)?;

}

env.visualize()?;

Ok(())

}

Each agent utilizes its policy network to predict actions based on the environment's state. The GNN policy processes graph-structured data, embedding the agent's state and interactions with neighbors into a latent space for policy computation. After executing an action, agents receive rewards (based on a penalty proportional to their squared distance from the origin) and update their policy using policy gradients. Communication between agents is facilitated through graph edges, defined by the proximity criterion (e.g., within a communication radius). This setup fosters cooperative or competitive dynamics, depending on the reward structure.

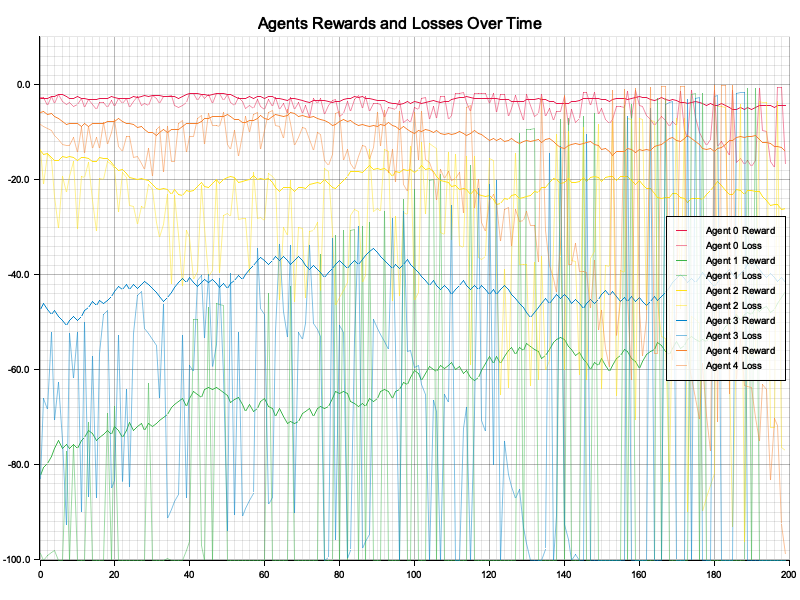

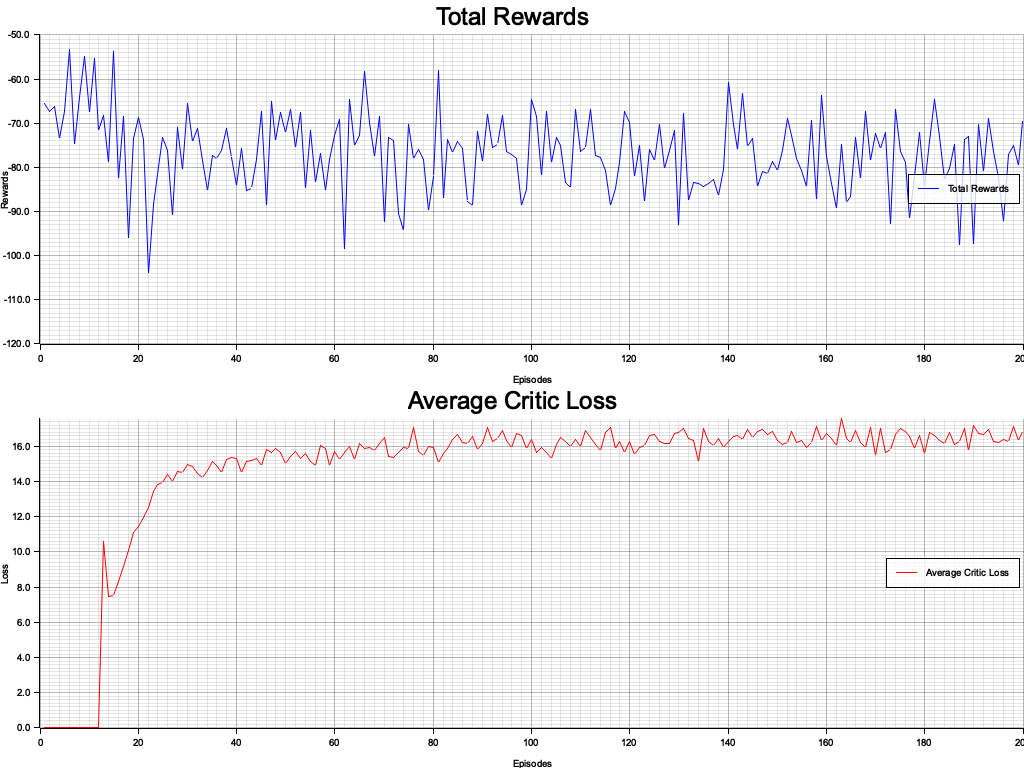

Figure 2: Plotters visualization of agents reward and loss.

The visualization reveals that agents exhibit distinct reward and loss trajectories over time. The rewards generally become less negative as agents optimize their positions closer to the origin, reflecting effective learning. However, fluctuations in loss indicate instability in some agents' learning processes, potentially due to the stochastic nature of policy updates or exploration. Agent-specific variations in reward and loss patterns suggest diversity in initial conditions or interactions, emphasizing the complexity of MARL environments. Further tuning of hyperparameters or introducing cooperative rewards could reduce instability and improve overall performance.

We will delve deeper into advanced MADRL algorithms, explore centralized and decentralized training methodologies, and examine real-world applications where MADRL can drive significant innovations. By harnessing Rust's capabilities alongside robust reinforcement learning techniques, you will be well-equipped to develop efficient, scalable, and reliable multi-agent systems that can tackle complex, dynamic environments.

18.2. Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has profoundly impacted various fields by enabling agents to learn optimal behaviors through interactions with their environments. Extending DRL to multi-agent settings introduces a spectrum of theoretical complexities and mathematical intricacies. This chapter delves into the foundational theories and mathematical formulations that underpin Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL). We will explore Multi-Agent Markov Decision Processes (MMDPs), Markov Games, equilibrium concepts, and the nuanced dynamics of centralized versus decentralized learning. Additionally, we will address the Credit Assignment Problem, a pivotal challenge in cooperative settings. To bridge theory with practice, we will demonstrate how to model these concepts in Rust, leveraging the language's robust type system and concurrency features. Finally, we will present Rust code examples that illustrate the setup of Markov Games and the computation of equilibrium states using state-of-the-art methods.

At the heart of MADRL lies the Multi-Agent Markov Decision Process (MMDP), an extension of the single-agent Markov Decision Process (MDP) framework to accommodate multiple interacting agents. An MMDP is formally defined by the tuple $\langle S, \{A_i\}, P, \{R_i\}, \gamma \rangle$, where:

$S$ is a finite set of states representing all possible configurations of the environment.

$\{A_i\}$ is a collection of action sets, with $A_i$ denoting the set of actions available to agent $i$.

$P: S \times A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_N \times S \rightarrow [0,1]$ is the state transition probability function, specifying the probability of transitioning to state $s'$ given the current state $s$ and joint actions $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N)$.

$\{R_i\}$ is a set of reward functions, where $R_i: S \times A_1 \times A_2 \times \dots \times A_N \times S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ defines the reward received by agent $i$ upon transitioning from state $s$ to state $s'$ due to joint actions $\mathbf{a}$.

$\gamma \in [0,1)$ is the discount factor, determining the present value of future rewards.

In an MMDP, each agent aims to maximize its own expected cumulative reward, considering the actions of other agents. The interdependence of agents' policies introduces a layer of complexity absent in single-agent MDPs, necessitating sophisticated solution concepts and learning algorithms.

Markov Games, also known as Stochastic Games, generalize MMDPs to encompass both cooperative and competitive interactions among agents. Formally, a Markov Game is defined by the tuple $\langle S, \{A_i\}, P, \{R_i\}, \gamma \rangle$, identical to an MMDP. The key distinction lies in the nature of the reward functions $\{R_i\}$:

Cooperative Games: All agents share a common reward function, leading to fully cooperative behavior. The objective is to maximize the collective reward.

Competitive Games: Agents have opposing objectives, often modeled as zero-sum games where one agent's gain is another's loss.

Mixed Games: Environments where agents exhibit both cooperative and competitive behaviors, necessitating a balance between individual and collective objectives.

Markov Games provide a versatile framework for modeling a wide range of multi-agent interactions, allowing researchers and practitioners to analyze and design algorithms tailored to specific interaction dynamics.

In multi-agent systems, equilibrium concepts are fundamental for analyzing and predicting stable strategy profiles, where no individual agent has an incentive to deviate unilaterally. These concepts provide the theoretical underpinnings for understanding how agents interact and adapt their strategies in dynamic, multi-agent environments. They help to characterize the conditions under which agents reach stability in their decision-making processes, ensuring that their collective behavior leads to predictable and interpretable outcomes.

The Nash Equilibrium represents one of the most well-established concepts in this domain. A joint policy $\boldsymbol{\pi}^ = (\pi_1^, \pi_2^, \dots, \pi_N^)$is considered a Nash Equilibrium if no agent can improve its expected reward by unilaterally deviating from its assigned policy $\pi_i^$, given that all other agents adhere to their respective policies $\boldsymbol{\pi}_{-i}^$. Formally, for every agent $i$, the expected cumulative reward under its policy $\pi_i^$ and others' policies $\boldsymbol{\pi}_{-i}^$ is at least as high as that achievable by any alternative action $a_i$. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

$$\mathbb{E}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_i(s_t, \mathbf{a}_t) \mid \pi_i^*, \boldsymbol{\pi}_{-i}^* \right] \geq \mathbb{E}\left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t R_i(s_t, a_i, \boldsymbol{\pi}_{-i}^*) \mid \pi_i^*, \boldsymbol{\pi}_{-i}^* \right].$$

Here, $R_i$ denotes the reward for agent $i$, and $\gamma$ represents a discount factor. Nash Equilibrium highlights the strategic stability of multi-agent systems, as it ensures that no agent can unilaterally benefit by deviating from its prescribed policy.

Correlated Equilibrium extends the Nash framework by incorporating a coordination mechanism, such as a correlation device, that recommends strategies to agents. Unlike Nash Equilibrium, where agents act independently based on their own policies, Correlated Equilibrium allows for joint recommendations that agents agree to follow if doing so maximizes their expected rewards. This concept enables richer interactions by introducing the possibility of coordinated strategies that can potentially improve collective outcomes while maintaining individual rationality.

Another critical concept is Pareto Optimality, which focuses on the efficiency of reward allocations among agents. A joint policy is Pareto Optimal if there exists no alternative policy that can improve the expected reward of at least one agent without decreasing the expected reward of another. Unlike equilibrium concepts that emphasize strategic stability, Pareto Optimality prioritizes efficiency, ensuring that no resources or opportunities for reward are wasted. However, it does not necessarily guarantee fairness or stability, as some agents may benefit disproportionately in Pareto Optimal solutions.

Understanding these equilibrium concepts is essential for designing algorithms that can converge to stable and efficient policy profiles in multi-agent reinforcement learning. By incorporating these principles, researchers and practitioners can build systems that achieve strategic stability (Nash and Correlated Equilibria) while also considering efficiency (Pareto Optimality). These concepts not only provide theoretical guarantees but also guide the development of practical solutions in real-world multi-agent environments.

Centralized and decentralized learning are two foundational paradigms in multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), each offering distinct strengths and trade-offs. Centralized learning involves a central entity that has access to the observations, actions, and potentially the rewards of all agents during the training phase. This centralized controller enables agents to coordinate their policies effectively, facilitating better information sharing and leveraging joint experiences to enhance learning outcomes. One of the key advantages of centralized learning is its ability to mitigate non-stationarity by explicitly accounting for the policies of all agents within the system. However, centralized approaches often struggle with scalability as the number of agents increases, leading to a combinatorial explosion in the complexity of joint policies. Furthermore, centralized learning may not be feasible in decentralized environments where agents operate independently or face constraints on communication and data sharing.

In contrast, decentralized learning allows each agent to independently learn its policy based on its own local observations and experiences. Agents in this paradigm do not have access to global information about the environment or the actions of other agents, which makes decentralized learning more scalable and suitable for large-scale systems. Additionally, decentralized learning is inherently robust to communication failures, as agents operate autonomously without relying on centralized coordination. However, this approach faces significant challenges from non-stationarity, as the environment for each agent dynamically changes due to the concurrently evolving policies of other agents. Techniques such as parameter sharing, where agents share parts of their policy networks, and independent Q-learning, which treats other agents as part of the environment, are commonly employed to address these challenges. Nevertheless, these methods are not always sufficient to fully resolve the complexities introduced by non-stationarity.

The choice between centralized and decentralized learning depends on the specific characteristics of the application, including the degree of interdependence among agents, the scale of the system, and the operational constraints such as communication and computational resources. Centralized learning may be more suitable for environments where coordination and information sharing are critical, whereas decentralized learning is better suited for scenarios requiring scalability, autonomy, and robustness to communication limitations.Cooperative, mixed and competitive dynamics in MADRL.

The nature of agent interactions profoundly influences the design and effectiveness of learning algorithms in MARL.

Cooperative Dynamics: In fully cooperative settings, agents share a common objective and work collectively to maximize a shared reward function. This alignment simplifies the learning process, as agents can benefit from sharing information, coordinating actions, and jointly optimizing policies. Techniques such as joint policy optimization and centralized training with decentralized execution are particularly effective in these scenarios.

Competitive Dynamics: In competitive environments, agents have opposing objectives, often leading to zero-sum or general-sum games. Here, agents must anticipate and counteract the strategies of adversaries, employing game-theoretic approaches to find equilibrium strategies. The learning process becomes more complex due to the strategic interactions and the need to adapt to the evolving policies of opponents.

Mixed Dynamics: Many real-world scenarios involve a combination of cooperative and competitive interactions. For instance, in team-based competitions, agents may collaborate within their team while competing against opposing teams. Balancing individual and collective objectives necessitates more sophisticated algorithms that can navigate the trade-offs between cooperation and competition.

Understanding the dynamics of agent interactions is crucial for selecting appropriate learning strategies and ensuring effective policy convergence.

The Credit Assignment Problem in multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) focuses on determining how to accurately attribute each agent’s contribution to the collective outcome, particularly in cooperative settings where rewards are shared among agents. Proper reward attribution is critical for ensuring that each agent receives meaningful feedback for its actions, which in turn facilitates effective policy updates and drives learning in the desired direction. Addressing this problem is essential for aligning individual agent behaviors with the global objectives of the system.

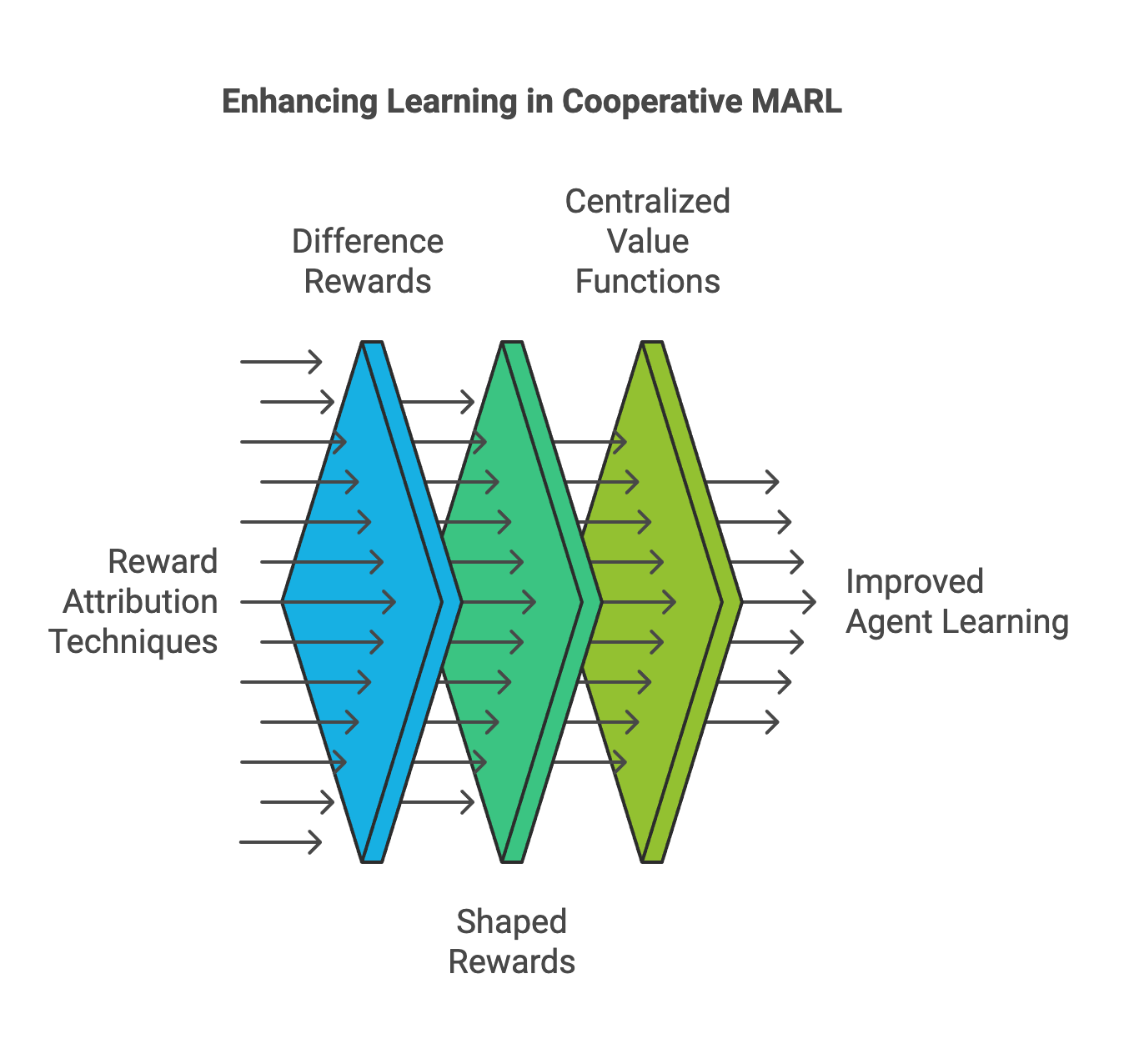

Figure 3: Improving agent learning in cooperative MARL.

One prominent approach to tackling the Credit Assignment Problem is the use of difference rewards. These rewards isolate the impact of an individual agent by comparing the total reward achieved with and without the agent's contribution. By calculating the difference, this technique provides agents with a clearer understanding of their specific role in achieving the collective outcome, thus encouraging them to optimize their actions accordingly. Another approach is shaped rewards, where the reward functions are designed to provide agents with additional feedback based on intermediate objectives or their local performance. This method bridges the gap between local and global goals, guiding agents incrementally toward the overall objective.

Centralized value functions offer another solution by employing a centralized critic to evaluate the joint actions of all agents. This centralized perspective allows the critic to derive tailored feedback for each agent based on the collective state-action value. By considering the interplay between all agents, centralized value functions provide more comprehensive and context-aware evaluations, enhancing the agents’ ability to learn coordinated strategies.

These techniques significantly improve the learning process in cooperative MARL by ensuring that rewards are distributed in a precise and actionable manner. Proper credit assignment not only accelerates the convergence of learning algorithms but also enhances the overall efficiency and effectiveness of cooperative systems, enabling agents to work together seamlessly to achieve shared goals.

Rust's strong type system and concurrency features make it an ideal language for implementing complex mathematical models in MARL. By leveraging Rust's safety guarantees and performance, developers can create robust and efficient implementations of MMDPs and Markov Games.

To begin modeling MMDPs and Markov Games in Rust, we can utilize crates such as ndarray for numerical computations, serde for serialization, and petgraph for managing agent interactions through graph structures. Additionally, Rust's ownership model ensures memory safety, which is crucial when dealing with concurrent agent processes.

Computing equilibria in multi-agent simulations involves implementing algorithms that can identify stable strategy profiles where no agent has an incentive to deviate unilaterally. In Rust, this can be achieved by translating mathematical formulations of equilibrium concepts into efficient algorithms.

For instance, computing a Nash Equilibrium in a Markov Game can involve iterative methods such as best-response dynamics or fixed-point algorithms. These methods require careful handling of policy updates and convergence criteria to ensure accurate and reliable results.

Below is a comprehensive Rust code example that demonstrates the setup of a Markov Game and the computation of Nash Equilibrium states using state-of-the-art methods. The code introduces a Markov Game model for multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), where multiple agents interact within a shared environment. Each agent is equipped with a strategy and a learning mechanism, modeled using a MarkovGame structure. The agents navigate a 2D grid, adjusting their positions and strategies dynamically based on interactions with other agents. The model incorporates an interaction graph to simulate agent relationships and uses a reward matrix to evaluate the quality of these interactions, computed as a function of distance between agents.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

ndarray = "0.16.1"

petgraph = "0.6.5"

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

serde = "1.0.215"

tch = "0.12.0"

use ndarray::Array2;

use petgraph::graph::{Graph, NodeIndex};

use petgraph::Undirected;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use rand::prelude::*;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::error::Error;

// Enhanced Agent structure with strategy and learning capabilities

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

struct Agent {

id: usize, // Unique identifier for the agent

node_index: NodeIndex, // Node index in the interaction graph

position: Vector2D, // Position in 2D space

strategy: Vec<f64>, // Agent's strategy vector

learning_rate: f64, // Learning rate for strategy updates

path: Vec<Vector2D>, // Path of the agent during the simulation

}

// 2D Vector type for easier manipulation

type Vector2D = (f64, f64);

// Define the State of the environment with more comprehensive tracking

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct GameState {

positions: Vec<Vector2D>, // Positions of all agents

timestep: usize, // Current timestep

}

// Enhanced Markov Game structure with more sophisticated mechanics

struct MarkovGame {

agents: Vec<Agent>, // List of agents in the game

interaction_graph: Graph<usize, (), Undirected>, // Graph representing interactions

state: GameState, // Current state of the game

transition_probabilities: Array2<f64>, // Transition probabilities for state changes

reward_matrix: Array2<f64>, // Matrix of rewards between agents

gamma: f64, // Discount factor for rewards

}

impl MarkovGame {

// Initialize the game with agents and interaction graph

fn new(num_agents: usize, map_size: f64) -> Self {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let mut agents = Vec::with_capacity(num_agents);

// Initialize the interaction graph

let mut graph = Graph::<usize, (), Undirected>::new_undirected();

// Create agents with strategic initial positions

let node_indices: Vec<NodeIndex> = (0..num_agents)

.map(|id| graph.add_node(id))

.collect();

for (id, &node_index) in node_indices.iter().enumerate() {

let position = (

rng.gen_range(0.0..map_size),

rng.gen_range(0.0..map_size),

);

// Initialize with random strategy

let strategy = (0..num_agents)

.map(|_| rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0))

.collect();

agents.push(Agent {

id,

node_index,

position,

strategy,

learning_rate: 0.1,

path: vec![position], // Start with initial position

});

}

// Fully connect the interaction graph

for i in 0..num_agents {

for j in (i + 1)..num_agents {

graph.add_edge(node_indices[i], node_indices[j], ());

}

}

// Initialize the state and matrices

let initial_state = GameState {

positions: agents.iter().map(|a| a.position).collect(),

timestep: 0,

};

let transition_probabilities = Array2::zeros((num_agents, num_agents));

let reward_matrix = Array2::zeros((num_agents, num_agents));

MarkovGame {

agents,

interaction_graph: graph,

state: initial_state,

transition_probabilities,

reward_matrix,

gamma: 0.95,

}

}

// Compute rewards based on agent interactions

fn compute_rewards(&mut self) {

println!("Transition Probabilities (Placeholder): {:?}", self.transition_probabilities);

for (i, agent) in self.agents.iter().enumerate() {

for (j, other) in self.agents.iter().enumerate() {

if i != j {

let distance = ((agent.position.0 - other.position.0).powi(2)

+ (agent.position.1 - other.position.1).powi(2))

.sqrt();

self.reward_matrix[(i, j)] = -self.gamma * distance; // Use gamma as discount factor

}

}

}

}

// Perform a single simulation step

fn step(&mut self) {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

println!("\n--- Step {} ---", self.state.timestep + 1);

// Update agent positions and strategies

for agent in &mut self.agents {

// Log node index usage

println!("Agent Node Index: {}", agent.node_index.index());

let dx = rng.gen_range(-1.0..1.0) * agent.strategy.iter().sum::<f64>();

let dy = rng.gen_range(-1.0..1.0) * agent.strategy.iter().sum::<f64>();

agent.position.0 = (agent.position.0 + dx).clamp(0.0, 10.0);

agent.position.1 = (agent.position.1 + dy).clamp(0.0, 10.0);

agent.path.push(agent.position);

agent.strategy = agent.strategy

.iter()

.map(|&s| s + agent.learning_rate * rng.gen_range(-0.1..0.1))

.map(|s| s.clamp(0.0, 1.0))

.collect();

println!(

"Agent {} | Position: {:?} | Strategy: {:?}",

agent.id, agent.position, agent.strategy

);

}

// Compute rewards and print the reward matrix

self.compute_rewards();

println!("Reward Matrix:");

for i in 0..self.agents.len() {

for j in 0..self.agents.len() {

print!("{:>8.2} ", self.reward_matrix[(i, j)]);

}

println!();

}

// Update the game state and print

self.state.positions = self.agents.iter().map(|a| a.position).collect();

self.state.timestep += 1;

println!(

"Updated State | Positions: {:?} | Timestep: {}",

self.state.positions, self.state.timestep

);

}

// Visualize agent trajectories

fn visualize_trajectories(&self, filename: &str) -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new(filename, (800, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Agent Trajectories", ("Arial", 30).into_font())

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0.0..10.0, 0.0..10.0)?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

for (i, agent) in self.agents.iter().enumerate() {

chart.draw_series(

agent.path.windows(2).map(|window| {

let start = window[0];

let end = window[1];

PathElement::new(

vec![start, end],

ShapeStyle::from(&Palette99::pick(i)).stroke_width(2),

)

}),

)?;

chart.draw_series(std::iter::once(Circle::new(

agent.position,

5,

ShapeStyle::from(&Palette99::pick(i)).filled(),

)))?

.label(format!("Agent {}", i))

.legend(move |(x, y)| {

Rectangle::new(

[(x - 5, y - 5), (x + 5, y + 5)],

ShapeStyle::from(&Palette99::pick(i)).filled(),

)

});

}

chart.configure_series_labels()

.border_style(&BLACK)

.draw()?;

root.present()?;

Ok(())

}

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let num_agents = 5;

let map_size = 10.0;

let num_steps = 900;

let mut game = MarkovGame::new(num_agents, map_size);

println!("Initial Interaction Graph:");

for edge in game.interaction_graph.edge_indices() {

let (source, target) = game.interaction_graph.edge_endpoints(edge).unwrap();

println!("Edge: {} -> {}", source.index(), target.index());

}

for _step in 1..=num_steps { // Use `_step` to suppress unused variable warning

game.step();

}

game.visualize_trajectories("agent_trajectories.png")?;

Ok(())

}

The MARL model operates by simulating steps in which agents move and adapt their strategies to maximize their rewards. At each timestep, agents update their positions based on their strategies, which are iteratively refined using a learning rate to encourage better performance. Rewards are computed based on pairwise distances between agents, emphasizing proximity as a determinant of interaction quality. The visualization highlights the trajectories of agents over time, showcasing their movements and interactions within the environment.

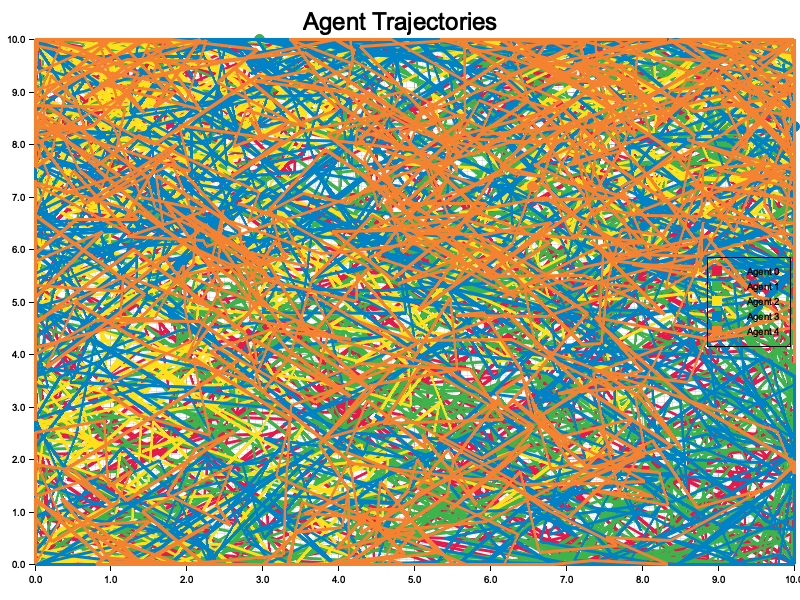

Figure 4: Plotters visualization of agents trajectories in the game.

The visualization of agent trajectories depicts the movement patterns of multiple agents over time within a bounded 2D environment. Each line represents the path of a single agent, with distinct colors assigned for clarity. The dense and overlapping trajectories indicate a high level of interaction among agents, suggesting frequent changes in direction and position as they adapt their strategies. The scattered and crisscrossing paths highlight the dynamic nature of the simulation, where agents explore the environment while responding to interactions with others. The extensive overlap may imply competitive or cooperative behaviors, depending on the reward structure driving the agents. This visualization effectively demonstrates the complexity and richness of the multi-agent system's dynamics.

As we advance to subsequent sections, we will delve deeper into advanced MARL algorithms, explore specialized equilibrium computation methods, and examine real-world applications where the theoretical and practical insights discussed herein can be applied to develop effective and scalable multi-agent systems.

18.3. Core Algorithms and Learning Paradigms in MADRL

Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) encompasses a diverse set of algorithms and learning paradigms designed to address the complexities of environments where multiple agents interact, cooperate, or compete. Unlike single-agent reinforcement learning, where the focus is on an isolated agent optimizing its cumulative reward, MADRL operates in environments where the actions of one agent influence the learning and behavior of others. This interconnectedness necessitates specialized algorithms and paradigms that account for the dynamic interplay among agents, making MADRL both a fascinating and challenging domain within artificial intelligence.

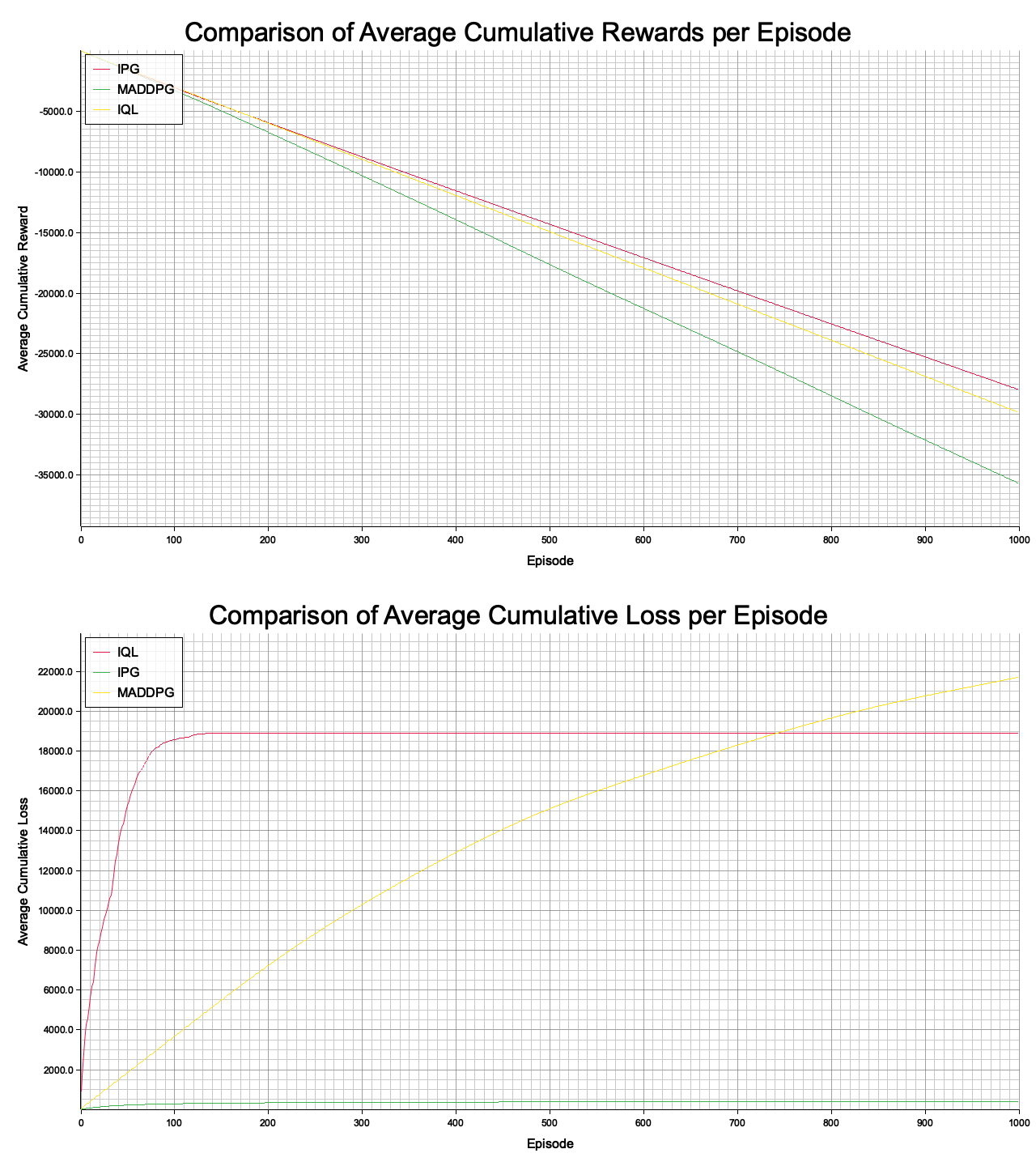

Figure 5: Common process of MADRL modeling adopted in RLVR.

This section provides a detailed exploration of the core algorithms that underpin MADRL, offering a blend of theoretical insights and practical guidance. We begin with fundamental approaches such as Independent Learning, where each agent independently learns its policy without direct coordination with others. While simple and scalable, this approach faces significant challenges in non-stationary environments, as agents must adapt to constantly changing dynamics influenced by the actions of others. To address this, more sophisticated paradigms like Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) have been developed. CTDE leverages centralized coordination during the training phase to optimize agent policies while enabling decentralized, independent decision-making during execution. This framework has become a cornerstone of modern MADRL, striking a balance between scalability and coordination.

Building on these foundational paradigms, we delve into advanced methods such as Multi-Agent Actor-Critic algorithms, which combine the policy optimization capabilities of actor-critic methods with mechanisms for inter-agent coordination. Among these, the Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) algorithm has emerged as a powerful approach for continuous action spaces. MADDPG employs a centralized critic that leverages information from all agents to evaluate actions while maintaining decentralized actors for policy execution. This architecture allows for seamless coordination in cooperative tasks and strategic competition in adversarial settings.

In addition to the core algorithms, this section explores key conceptual considerations that guide the design and application of MADRL systems. One of the most significant challenges in MADRL is non-stationarity, where the environment’s dynamics continually change as agents learn and adapt. Strategies such as stabilizing training with experience replay buffers, employing centralized critics, and leveraging predictive models are discussed to mitigate this issue. Furthermore, we explore exploration techniques tailored to multi-agent environments, including joint exploration methods that encourage collective discovery of optimal strategies and individual exploration strategies that maintain diversity in agent behavior.

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, the section includes comprehensive practical sections focused on implementing MADDPG and comparing various MADRL algorithms using Rust. Rust’s performance-oriented design, strong type safety, and concurrency features make it an excellent choice for implementing scalable and efficient MADRL frameworks. We guide you through the process of implementing MADDPG in Rust, detailing the creation of actor and critic networks, training loops, and the integration of centralized critics. Additionally, the chapter provides a comparative analysis of different MADRL algorithms, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and application contexts.

By combining theoretical foundations with practical implementations, this chapter aims to equip you with a robust understanding of MADRL. Whether you are exploring cooperative robotics, optimizing autonomous vehicle coordination, or tackling distributed resource management, the insights and tools provided here will serve as a solid foundation for advancing your expertise in this dynamic and rapidly evolving field.

Independent Learning is a foundational approach in MADRL where each agent treats other agents as part of the environment. This paradigm extends traditional single-agent reinforcement learning algorithms to multi-agent settings without explicit coordination or communication among agents. Two primary methods under Independent Learning are Independent Q-Learning and Independent Policy Gradients.

Independent Q-Learning involves each agent maintaining its own Q-function, $Q_i(s, a_i)$, which estimates the expected cumulative reward for taking action $a_i$ in state $s$. Each agent updates its Q-function independently using experiences gathered from interactions with the environment and other agents. The update rule for agent iii is similar to single-agent Q-Learning:

$$ Q_i(s_t, a_i^t) \leftarrow Q_i(s_t, a_i^t) + \alpha \left[ r_i^t + \gamma \max_{a_i'} Q_i(s_{t+1}, a_i') - Q_i(s_t, a_i^t) \right] $$

Here, $\alpha$ is the learning rate, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, $r_i^t$ is the reward received by agent $i$ at time $t$, and $a_i'$ represents the possible actions in the next state.

Independent Policy Gradients extend this concept to policy-based methods, where each agent optimizes its policy $\pi_i(a_i | s)$ independently using gradient ascent on expected rewards. The policy gradient update for agent iii can be expressed as:

$$ \nabla_{\theta_i} J(\theta_i) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_i} \left[ \nabla_{\theta_i} \log \pi_i(a_i | s) Q_i(s, a_i) \right] $$

Here, $\theta_i$ represents the parameters of agent $i$ policy, and $J(\theta_i)$ is the expected return.

While Independent Learning is simple to implement and scales well with the number of agents, it often suffers from the non-stationarity of the environment caused by simultaneous learning of multiple agents, leading to unstable learning dynamics.

Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) is a paradigm designed to address the challenges posed by multi-agent environments, particularly non-stationarity and partial observability. In CTDE, agents are trained in a centralized manner, leveraging global information about the environment and other agents, but execute their policies in a decentralized fashion based solely on their local observations. The main principles of CTDE:

Centralized Training: During training, a centralized controller or critic has access to the observations and actions of all agents. This enables the learning algorithm to account for the interactions and dependencies among agents, leading to more stable and coordinated policy updates.

Decentralized Execution: Once training is complete, each agent operates independently, relying only on its local observations and learned policy. This ensures scalability and robustness, as agents do not depend on centralized communication during deployment.

Consider a multi-agent system with $N$ agents. Let $\mathbf{a} = (a_1, a_2, \dots, a_N)$ denote the joint action of all agents, and $\mathbf{o} = (o_1, o_2, \dots, o_N)$ represent the joint observations. In CTDE, the centralized critic for agent $i$ can be modeled as:

$$ Q_i^{\text{centralized}}(s, \mathbf{a}) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_i^t \mid s_0 = s, \mathbf{a}_0 = \mathbf{a} \right] $$

Here, $Q_i^{\text{centralized}}$ takes into account the joint actions and global state, allowing for more informed updates to each agent's policy.

By separating the training and execution phases, CTDE balances the benefits of centralized information during learning with the scalability and flexibility of decentralized execution, making it a widely adopted framework in MADRL.

Multi-Agent Actor-Critic (MAAC) methods combine the strengths of actor-critic architectures with multi-agent learning dynamics. These methods utilize separate actor (policy) and critic (value) networks for each agent, allowing for simultaneous policy optimization and value estimation.

MADDPG, or Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient, is a widely used algorithm in multi-agent actor-critic (MAAC) frameworks, specifically designed to handle continuous action spaces in multi-agent environments. Building on the principles of the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm, MADDPG introduces a crucial enhancement for multi-agent systems by employing centralized critics and decentralized actors. This dual approach allows agents to effectively learn policies that account for both their local observations and the global interactions within the environment, making it well-suited for tasks requiring coordination or competition among agents.

For each agent in the system, MADDPG maintains an actor network $\mu_i(s_i | \theta_i^\mu)$, which is responsible for generating actions $a_i$ based solely on the agent’s local observations $s_i$. This decentralized design ensures scalability and robustness, as each agent operates independently when deciding its actions. Simultaneously, MADDPG employs a centralized critic network $Q_i(s, \mathbf{a} | \theta_i^Q)$ for each agent, which evaluates the quality of the joint actions $\mathbf{a}$ of all agents in the system, given the global state $s$. The centralized critic utilizes this global perspective to provide feedback during training, enabling agents to learn how their actions influence not only their individual outcomes but also the overall system's performance.

This combination of decentralized actors and centralized critics allows MADDPG to address the non-stationarity challenges inherent in multi-agent learning, where the environment's dynamics are influenced by the changing policies of all agents. By leveraging the global information available to the centralized critics during training, MADDPG ensures more accurate value estimation and facilitates stable convergence. At the same time, the decentralized actors ensure that the learned policies can be executed independently during testing, making MADDPG a powerful and practical approach for solving complex multi-agent problems in continuous action spaces.The training process in multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) involves coordinated updates to both the actor and critic networks for each agent to optimize their policies and value functions. In the actor update, each agent adjusts its actor parameters $\theta_i^\mu$ using a policy gradient approach. This is based on the centralized critic's feedback, which evaluates the quality of actions taken by the agent in the given state. The gradient $\nabla_{\theta_i^\mu} J$ is computed as the expectation of the product of two terms: the gradient of the policy function $\mu_i(s_i | \theta_i^\mu)$ with respect to the actor parameters and the gradient of the centralized value function $Q_i(s, \mathbf{a} | \theta_i^Q)$ with respect to the agent's action $a_i$. This formulation ensures that the actor network learns to propose actions that maximize the estimated value of the centralized critic.

For the critic update, the centralized critic parameters $\theta_i^Q$ are optimized to minimize the temporal difference (TD) error, a standard metric in reinforcement learning. The TD error is defined as the difference between the current estimate of the value function $Q_i(s, \mathbf{a} | \theta_i^Q)$ and the target value $y_i$. The target $y_i$ incorporates the immediate reward $r_i$ and a discounted estimate of future returns, derived from the target critic network and the actions suggested by the target actor networks for the next state $s'$. By minimizing this error, the critic network learns to provide more accurate value estimates, which are essential for guiding the actor updates.

To stabilize the training process, soft updates are performed on the target networks. This involves gradually updating the target network parameters $\theta_i^{\text{target}}$ to track the current network parameters $\theta_i$, with a small step size $\tau$ (e.g., 0.001). The update rule $\theta_i^{\text{target}} \leftarrow \tau \theta_i + (1 - \tau) \theta_i^{\text{target}}$ ensures that the target networks change slowly, reducing oscillations and divergence in training. These target networks serve as stable references for computing the target values in the critic update, thus enhancing the convergence of the training process.

MADDPG effectively leverages centralized critics to provide rich feedback for decentralized actors, enabling coordinated policy updates that account for the actions of other agents. This approach mitigates the non-stationarity inherent in multi-agent environments and facilitates more stable and efficient learning.

Selecting the appropriate Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) algorithm is a critical step in designing a successful multi-agent system. The decision-making process involves evaluating several key factors, such as the nature of agent interactions, the complexity of the environment, scalability demands, communication constraints, and computational resources. Each of these factors plays a pivotal role in determining which algorithm will yield the best performance under specific conditions.

The type of environment significantly influences algorithm selection. In fully cooperative settings, where agents work toward shared objectives, centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) frameworks and algorithms like MADDPG are highly effective. These approaches utilize centralized critics to optimize joint actions while allowing agents to act independently during execution. In contrast, competitive or mixed environments, which involve adversarial or hybrid interactions, benefit from algorithms that incorporate game-theoretic principles, such as MADDPG. These methods account for opposing objectives and strategic behaviors among agents, enabling effective decision-making in competitive scenarios.

The action space also dictates algorithm choice. For tasks involving discrete action spaces, simpler methods like Independent Q-Learning or independent policy gradient techniques may suffice, as they handle discrete decision-making efficiently. However, continuous action spaces require more sophisticated approaches, such as actor-critic algorithms like MADDPG, which are designed to handle the nuances of continuous control and gradient-based optimization effectively. These algorithms ensure smooth and precise action selection in continuous environments.

Scalability is another crucial factor, particularly in environments with many agents. Decentralized learning approaches, which enable agents to train independently using local information, offer better scalability by reducing computational and coordination overhead. Techniques like parameter sharing further enhance scalability by streamlining the training process. Conversely, centralized training methods can struggle as the number of agents increases, since the complexity of modeling joint interactions grows exponentially with the size of the agent pool.

Communication constraints also play a vital role. In environments where agents cannot communicate or share information, decentralized algorithms that rely solely on local observations are indispensable. These methods allow agents to function autonomously and adapt based on their own experiences. On the other hand, if communication is possible, centralized training methods can harness shared information to improve coordination and optimize collective behavior, leading to more efficient learning outcomes.

Computational resources must also be considered. Centralized approaches generally demand significant computational power due to the need to process and integrate global information. In contrast, decentralized methods distribute the computational workload across individual agents, making them more resource-efficient and suitable for resource-constrained scenarios. Additionally, centralized training methods tend to offer more stable learning dynamics, as they mitigate the non-stationarity caused by concurrently adapting agent policies. Independent learning methods, while computationally lighter, may struggle to converge in highly dynamic and interactive environments.

By thoroughly analyzing these factors, practitioners can make informed decisions when selecting MADRL algorithms. Tailoring the algorithm to align with the specific requirements and constraints of the application ensures effective learning and robust performance in multi-agent systems, whether the focus is on cooperation, competition, or a mix of both.

Non-stationarity is a significant challenge in MADRL, arising from the simultaneous learning and adaptation of multiple agents. As each agent updates its policy based on its experiences, the environment becomes non-stationary from the perspective of other agents, complicating the learning process.

Managing non-stationarity is a critical challenge in multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), as agents’ policies evolve dynamically, altering the environment for others. Strategies to address this issue involve methods that stabilize learning, reduce variability, and promote coordination among agents. Centralized training is a prominent approach, where centralized critics or controllers access joint actions and states to provide stable learning signals. By evaluating agents’ behaviors collectively, this method mitigates the disruptive effects of policy changes by individual agents, enabling more consistent learning.

Experience replay buffers are another effective strategy. By maintaining agent-specific or shared buffers, these mechanisms break temporal correlations in the training data. They allow agents to train on diverse experiences from the past, smoothing out fluctuations caused by rapidly changing policies in the environment. This retrospective learning aids in overcoming instability, particularly in environments where policies adapt frequently.

Policy regularization further stabilizes learning by discouraging drastic updates to agent policies. By incorporating regularization terms into the loss function, this technique enforces gradual changes in policies, ensuring smoother convergence and reducing abrupt shifts that can destabilize the multi-agent system. Similarly, opponent modeling helps agents adapt to the evolving strategies of their counterparts. By explicitly predicting or estimating other agents' policies, an agent can better anticipate their actions and reduce the unpredictability introduced by concurrent policy learning.

Communication and coordination also play a crucial role in mitigating non-stationarity. When agents are able to exchange information and align their objectives, it fosters more coordinated updates to their policies, minimizing conflicting behaviors. This approach is particularly beneficial in cooperative environments, where shared learning objectives can lead to faster convergence. Parameter sharing, where similar agents use shared network parameters, provides another layer of stability by reducing policy variability across agents. This method is highly effective in homogeneous environments with multiple agents performing similar tasks.

Lastly, multi-agent exploration strategies contribute to stabilizing the learning process by ensuring that agents explore the environment in a coordinated manner. By reducing conflicting or redundant exploratory actions, these techniques enable agents to learn more effectively from their interactions with the environment and with each other. Coordinated exploration not only reduces the learning noise but also improves overall efficiency.

By integrating these strategies, MARL systems can better manage the inherent non-stationarity of multi-agent environments. This leads to more reliable and efficient learning outcomes, enabling agents to adapt effectively while maintaining system stability.

Effective exploration is crucial in Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MADRL) to ensure that agents sufficiently explore the environment and discover optimal policies. In multi-agent settings, exploration becomes more complex due to the need for coordinated exploration and managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off across multiple agents. Independent exploration is one approach where each agent explores the environment on its own, typically using strategies like epsilon-greedy or by adding noise to policy outputs. While this method is straightforward, it can lead to redundant or conflicting explorations, as agents may end up exploring the same areas without coordination.

Alternatively, joint exploration involves coordinating the exploration efforts of all agents to ensure a diverse and comprehensive exploration of the state-action space. This can be achieved through shared exploration policies or coordinated noise mechanisms, which help in covering different regions of the environment more effectively. Entropy-based exploration further enhances this process by encouraging policies to maintain high entropy, which ensures diverse action selection and prevents premature convergence to suboptimal policies. Techniques such as Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) can be adapted for multi-agent scenarios to incorporate entropy maximization.

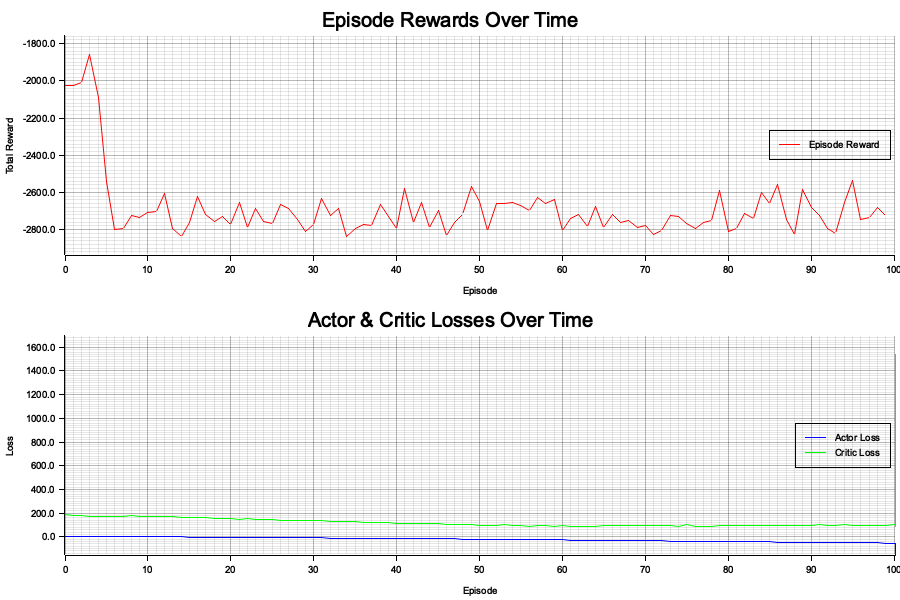

Figure 6: Exploration strategies in MADRL.

Curiosity-driven exploration integrates intrinsic motivation mechanisms where agents seek novel or surprising states based on prediction errors. This approach drives exploration in multi-agent environments by encouraging agents to explore states that are less predictable, thereby enhancing the overall exploration process. In cooperative settings, decentralized exploration with shared rewards allows agents to use shared or difference rewards to guide their exploration towards states that are collectively beneficial, promoting cooperation and reducing redundant efforts.

Hierarchical exploration introduces hierarchical policies where high-level policies guide exploration at different temporal scales. This can enhance exploration efficiency and coordination among agents by breaking down the exploration process into more manageable sub-tasks. Additionally, multi-agent bandit algorithms provide a structured approach to balancing exploration and exploitation across agents, which is particularly useful in dynamic environments where conditions can change rapidly.

Maximizing mutual information between agents' actions and environmental states is another technique that fosters coordinated exploration and enhances learning efficiency. By ensuring that the actions of agents are informative about the state of the environment, mutual information maximization helps in creating a more synchronized and effective exploration strategy.

When considering individual versus joint exploration, individual exploration allows agents to explore based on their own policies without considering the actions of others. While this approach is straightforward, it may lead to inefficient exploration in environments with high inter-agent dependencies. In contrast, joint exploration involves coordinating exploration efforts among agents, which can reduce redundancy and ensure that diverse regions of the state-action space are explored. Although joint exploration can be more effective in complex environments, it requires robust mechanisms for coordination.

Balancing exploration and exploitation in multi-agent settings requires thoughtful design of exploration strategies that account for the interactions and dependencies among agents. By carefully designing these strategies, the collective learning process can remain both efficient and effective, ensuring that all agents contribute to discovering optimal policies while minimizing redundant or conflicting explorations.

Implementing the Multi-Agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MADDPG) algorithm in Rust leverages the language's performance, safety, and concurrency features. Utilizing crates like tch-rs for tensor operations and neural network integration, and serde for model serialization, we can build a robust MADDPG implementation.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

ndarray = "0.16.1"

petgraph = "0.6.5"

plotters = "0.3.7"

prettytable = "0.10.0"

rand = "0.8.5"

serde = "1.0.215"

tch = "0.12.0"

use plotters::prelude::*; // For visualization

use tch::{

nn::{self, OptimizerConfig, VarStore},

Device, Kind, Tensor,

};

use rand::prelude::*;

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use prettytable::{Table, row};

// Hyperparameters

const STATE_DIM: i64 = 16;

const ACTION_DIM: i64 = 4;

const NUM_AGENTS: usize = 4;

const HIDDEN_DIM: i64 = 256;

const BUFFER_CAPACITY: usize = 100_000;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 64;

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99;

const TAU: f64 = 0.01;

const LR_ACTOR: f64 = 1e-3;

const MAX_EPISODES: usize = 200; // Increased to 200 episodes

const MAX_STEPS: usize = 5; // Adjusted for testing

// Replay Buffer

struct ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque<(Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)>,

}

impl ReplayBuffer {

fn new(capacity: usize) -> Self {

ReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque::with_capacity(capacity),

}

}

fn add(&mut self, transition: (Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)) {

if self.buffer.len() == self.buffer.capacity() {

self.buffer.pop_front();

}

self.buffer.push_back(transition);

}

fn sample(

&self,

batch_size: usize,

device: Device,

) -> Option<(Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)> {

if self.buffer.len() < batch_size {

return None;

}

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let samples = self

.buffer

.iter()

.choose_multiple(&mut rng, batch_size);

let states = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.0.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let actions = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.1.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let rewards = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.2.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let next_states = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.3.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

let dones = Tensor::stack(

&samples.iter().map(|x| x.4.shallow_clone()).collect::<Vec<_>>(),

0,

)

.to_device(device);

Some((states, actions, rewards, next_states, dones))

}

}

// Actor Network

struct ActorNetwork {

fc1: nn::Linear,

fc2: nn::Linear,

fc3: nn::Linear,

}