Chapter 19

Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning

"Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much." — Helen Keller

Chapter 19 delves into the sophisticated domain of Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL), merging the principles of federated learning with the dynamic decision-making capabilities of reinforcement learning. This chapter meticulously explores the mathematical underpinnings of FDRL, including distributed optimization and consensus mechanisms, providing a solid foundation for understanding how decentralized agents can collaboratively learn without centralizing sensitive data. It examines core algorithms adapted for federated settings, such as Federated Averaging and Federated Policy Gradient methods, highlighting their theoretical foundations and practical implementations. A significant emphasis is placed on communication protocols, privacy-preserving techniques, and scalability strategies, showcasing how Rust's performance-oriented features facilitate the development of efficient and secure FDRL systems. Through a blend of rigorous theoretical discussions, conceptual frameworks, and hands-on coding examples in Rust, Chapter 19 equips readers with the knowledge and skills to design, implement, and evaluate federated reinforcement learning models across diverse and real-world applications.

19.1. Introduction to Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning

As the landscape of artificial intelligence continues to evolve, the integration of federated learning with reinforcement learning has introduced a transformative approach known as Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL). This paradigm brings together the decentralized and privacy-preserving nature of federated learning with the interactive, decision-making capabilities of reinforcement learning, creating a framework that addresses some of the most pressing challenges in modern AI. By allowing agents to learn collaboratively across distributed environments while safeguarding sensitive data, FDRL embodies a shift towards scalable, ethical, and robust AI systems.

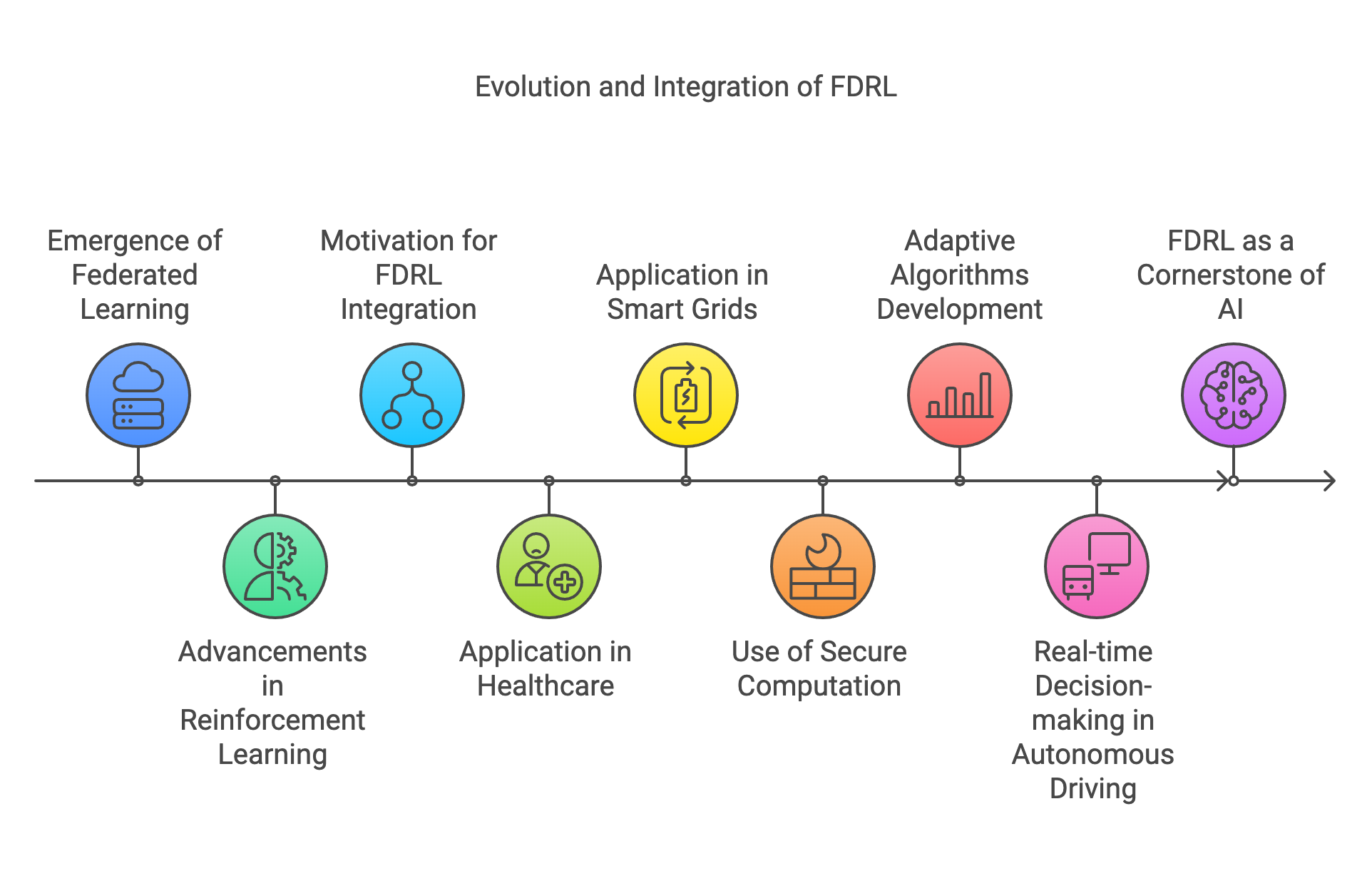

The evolution of FDRL is rooted in the independent development of its constituent fields. Federated learning emerged in the early 2010s as a response to increasing concerns over data privacy and the logistical challenges of centralized data aggregation. Organizations began exploring ways to train machine learning models directly on decentralized data sources, such as mobile devices or edge servers, without transferring sensitive data to central locations. This approach not only preserved privacy but also reduced the communication overhead associated with transmitting large datasets.

Figure 1: The natural evolution of federation learning in DRL.

Simultaneously, reinforcement learning advanced as a powerful framework for sequential decision-making, enabling agents to learn optimal policies through trial-and-error interactions with their environments. From its early applications in board games and robotics to its modern role in complex domains like healthcare and autonomous systems, RL demonstrated the ability to model and solve dynamic, interactive problems. However, traditional RL methods often relied on centralized architectures, where agents required access to extensive, aggregated data and computational resources.

The motivation for combining these two fields into FDRL arises from their complementary strengths and their ability to address the limitations of traditional centralized RL systems. In scenarios where data is distributed across multiple entities—such as hospitals, IoT devices, or autonomous vehicles—centralized RL is impractical due to data privacy concerns, bandwidth limitations, and regulatory constraints. Federated learning provides the solution by enabling agents to train locally and share only aggregated updates, ensuring that raw data remains secure and localized. By integrating reinforcement learning, FDRL extends this capability to interactive, decision-making tasks, allowing agents to optimize behaviors across decentralized systems.

One of the key motivations behind FDRL is its potential to democratize AI by harnessing the collective intelligence of distributed agents. In healthcare, for example, individual hospitals can train RL agents to optimize patient care protocols using their local data while contributing to a global model that benefits from diverse data sources. Similarly, in smart grids, distributed energy nodes can learn to balance loads and manage resources cooperatively without compromising sensitive usage data. This collaborative approach not only enhances the performance and generalization of the global model but also aligns with ethical principles by prioritizing privacy and inclusivity.

The evolution of FDRL has also been driven by advancements in distributed systems, secure computation, and scalable algorithms. Modern FDRL frameworks incorporate technologies such as secure multiparty computation (SMC) and differential privacy to ensure the confidentiality of agent updates. Additionally, adaptive algorithms have been developed to address the challenges of non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed) data, asynchronous updates, and varying computational capacities among agents. These innovations have made FDRL a viable solution for real-world applications where decentralization and privacy are critical.

Another significant motivation for FDRL is its potential to enable real-time, adaptive decision-making in dynamic and resource-constrained environments. In autonomous driving, for instance, vehicles equipped with RL agents can learn optimal driving strategies based on local conditions while contributing to a shared model that adapts to diverse traffic scenarios. In industrial automation, robots operating in distributed warehouses can collaboratively optimize logistics and resource allocation, improving efficiency and reducing costs.

As FDRL continues to mature, it is poised to become a cornerstone of AI systems designed for distributed, privacy-sensitive, and highly dynamic environments. By blending the strengths of federated and reinforcement learning, it addresses critical challenges in scalability, security, and adaptability, paving the way for a new era of collaborative intelligence. This chapter delves deeply into the theoretical foundations, key terminologies, and practical implementation strategies of FDRL, equipping readers with the knowledge and tools to leverage this paradigm in diverse domains. Through the use of Rust’s performance-oriented ecosystem, we demonstrate how to build and simulate decentralized learning environments, highlighting the unique capabilities of FDRL and its transformative potential.

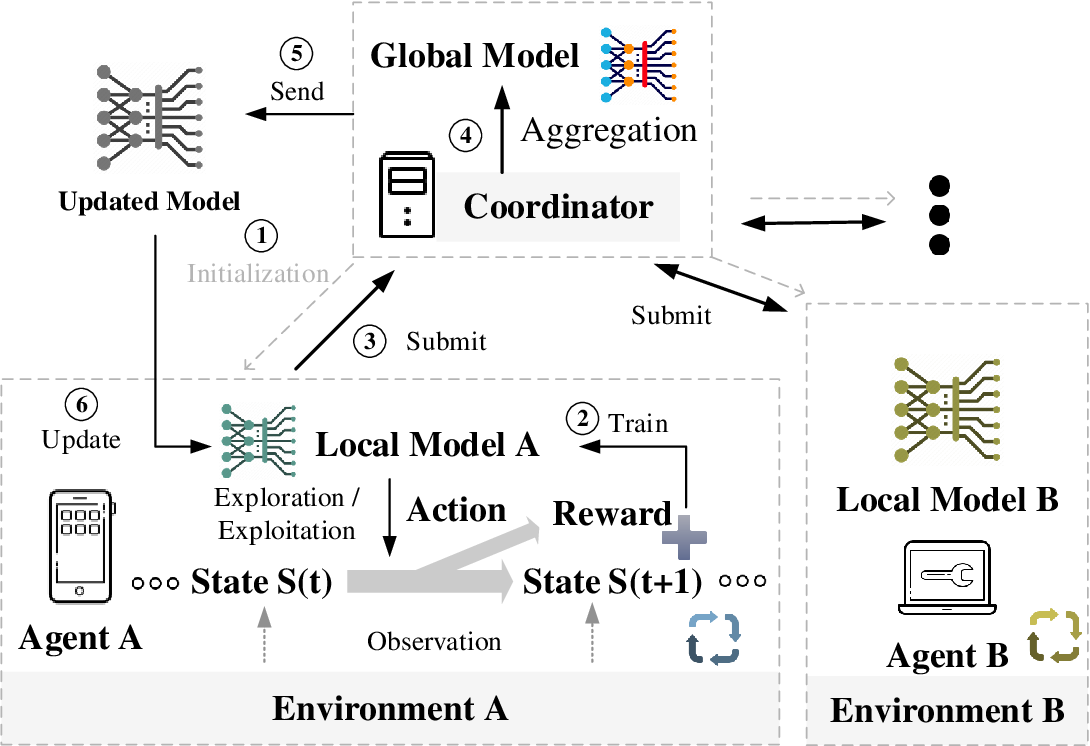

Formally, consider a set of $K$ federated agents, each with its own local environment $E_k$. Each agent $k$ maintains a local policy $\pi_k$ and learns from its experiences within $E_k$. The objective of FDRL is to optimize a global policy $\pi$ that aggregates the knowledge from all local policies without necessitating the sharing of raw data between agents. This approach not only enhances scalability but also addresses privacy concerns by ensuring that sensitive data remains localized.

Figure 2: Illustration of Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL).

The diagram illustrates the concept of FDRL, which enables distributed agents (e.g., Agent A and Agent B) to learn collaboratively while maintaining local control of their environments and data. Each agent interacts with its respective environment, observing states and executing actions that yield rewards. These interactions enable the training of a local model through reinforcement learning. Periodically, agents submit their locally updated models to a global coordinator. The coordinator aggregates the models, creating a global model that captures collective knowledge. This updated global model is then sent back to the agents, which integrate it into their local training processes. This decentralized approach leverages the advantages of shared learning while preserving privacy and reducing the need to centralize raw data. The cycle ensures efficient learning in a collaborative yet distributed manner, improving the performance of individual agents and the global system as a whole.

The mathematical underpinnings of FDRL are rooted in distributed optimization and consensus algorithms, which facilitate the coordination and synchronization of learning across multiple agents. The primary challenge in FDRL is to ensure that the aggregated global policy converges to an optimal or near-optimal solution despite the decentralized nature of data and computations.

Distributed Optimization: In FDRL, each agent $k$ aims to minimize a local loss function $L_k(\theta)$, where $\theta$ represents the parameters of the policy network. The global objective is to minimize the aggregated loss across all agents: $L(\theta) = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K L_k(\theta)$. This can be approached using algorithms such as Federated Averaging (FedAvg), where each agent performs local gradient descent updates on its loss function and periodically communicates the updated parameters to a central server for averaging: $\theta^{t+1} = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \theta_k^{t}$, where $\theta_k^{t}$ are the parameters of agent $k$ at iteration $t$.

Consensus Algorithms: Consensus algorithms ensure that all agents agree on certain variables or states, facilitating coherent policy updates. One common approach is the decentralized consensus, where agents iteratively share and update their parameters based on their neighbors' states $\theta_k^{t+1} = \theta_k^{t} + \alpha \sum_{j \in \mathcal{N}_k} (\theta_j^{t} - \theta_k^{t})$, here, $\mathcal{N}_k$ denotes the set of neighboring agents of agent $k$, and $\alpha$ is the consensus step size. This iterative process drives the agents' parameters towards a common consensus value, promoting synchronization across the network.

Understanding the terminology specific to Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) is essential for grasping its operational dynamics and implementation strategies. Federated agents are individual learning entities that operate in their unique local environments. Each agent maintains its own policy and learns from its interactions without sharing raw data. Local models, trained by these agents, capture agent-specific policies and value functions based on localized data and experiences. These local models are aggregated into a global model, which combines knowledge from all agents, serving as a reference to synchronize and update local policies. Effective communication protocols enable agents to exchange critical information, such as model parameters or gradients, while maintaining synchronization. To ensure privacy during these exchanges, privacy-preserving techniques like differential privacy and secure multi-party computation are often employed. Consensus algorithms further facilitate coordinated policy updates by enabling agents to agree on variables or states, ensuring consistency across the federated network.

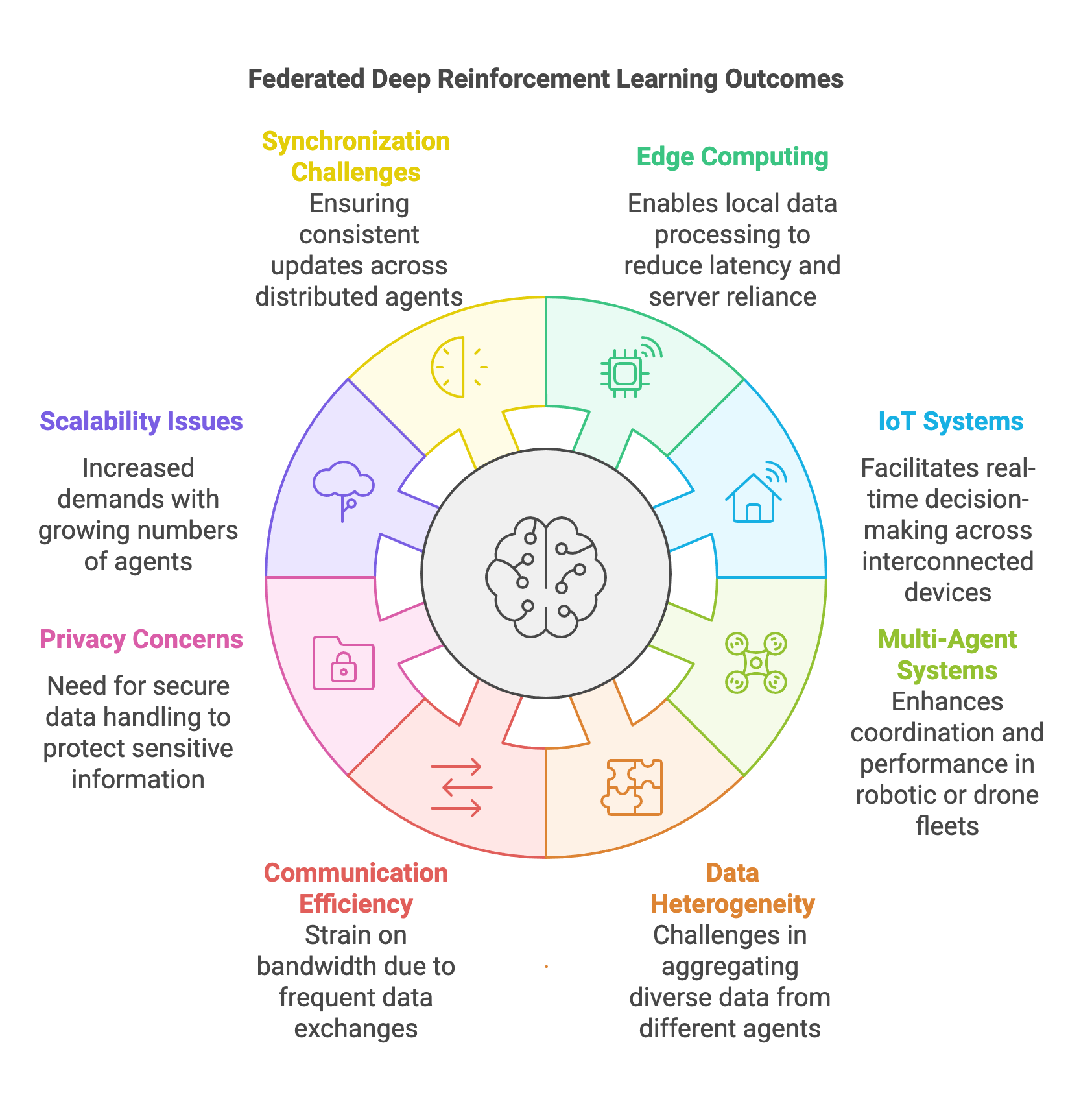

Figure 3: Scopes and applications of FDRL.

FDRL has immense potential in decentralized learning scenarios, especially in industries like edge computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), and multi-agent systems. In edge computing environments, data generated at the network’s periphery, such as from smartphones or IoT sensors, can be processed locally through FDRL, reducing latency and reliance on centralized servers. Similarly, IoT systems, with their vast network of interconnected devices, benefit from FDRL by enabling real-time decision-making and adaptability without overwhelming centralized infrastructure. In multi-agent systems like robotic swarms or drone fleets, FDRL allows individual agents to learn from their interactions while contributing to a collective learning objective, enhancing system coordination and performance.

Despite its benefits, FDRL poses challenges that must be addressed to realize its full potential. Data heterogeneity across agents often leads to non-identical, non-independent (non-IID) data distributions, complicating the aggregation of local models into a unified global model. Communication efficiency is another significant challenge, as frequent exchanges between agents and the central server can strain bandwidth and increase latency. Privacy concerns further complicate the system, necessitating techniques like secure aggregation to safeguard sensitive local data. Scalability is a critical concern as well, as the computational and communication demands of FDRL grow with the number of agents. Finally, ensuring synchronization and consistency across distributed agents is essential for effective learning, as delays or inconsistencies can impede convergence and lead to suboptimal outcomes.

FDRL also differs fundamentally from traditional centralized reinforcement learning (RL) in several aspects. Centralized RL relies on collecting and processing data in a unified environment, allowing for seamless optimization. FDRL, however, distributes data and computation across multiple agents, requiring decentralized learning strategies. This distributed approach makes FDRL inherently more scalable than centralized RL, which often faces bottlenecks as data volume and agent numbers increase. Privacy and security are another differentiating factor, with centralized RL requiring data aggregation that can raise concerns, whereas FDRL keeps data localized and employs privacy-preserving mechanisms. While centralized RL typically has minimal communication overhead post-data centralization, FDRL necessitates ongoing communication between agents and the central server, introducing additional overhead that needs efficient management. Lastly, FDRL offers greater flexibility and robustness to agent failures or network changes, whereas centralized RL systems are more prone to single points of failure and require substantial reconfiguration to adapt to changes.

Understanding these distinctions and challenges is critical for selecting and implementing the appropriate reinforcement learning paradigm based on the unique requirements of the application domain. FDRL’s ability to balance privacy, scalability, and decentralized learning positions it as a powerful approach for distributed systems and dynamic environments.

Implementing FDRL in Rust involves establishing a federated environment where multiple agents interact, learn, and communicate asynchronously. This code demonstrates a basic Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) simulation using Rust with asynchronous communication powered by the tokio crate. The system consists of a central server and multiple agents that communicate through asynchronous message passing. Each agent generates random model parameters and sends them to the central server, which then broadcasts these updates back to all agents, simulating the aggregation and synchronization of a global model in a federated learning context. The serde crate is used to serialize and deserialize data structures for seamless message exchanges between agents and the central server.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

tokio = { version = "1.42", features = ["full"] }

serde = { version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

rand = { version = "0.8", features = ["std_rng"] }

use tokio::sync::mpsc;

use serde::{Serialize, Deserialize};

use tokio::task;

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::rngs::StdRng;

use rand::{Rng, SeedableRng};

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

struct ModelUpdate {

agent_id: usize,

parameters: Vec<f32>,

}

struct CentralServer {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>,

}

impl CentralServer {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>) -> Self {

CentralServer { receiver, senders }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

while let Some(update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Central Server received update from Agent {}", update.agent_id);

for (&agent_id, sender) in &self.senders {

sender.send(update.clone()).await.unwrap();

println!("Central Server sent aggregated parameters to Agent {}", agent_id);

}

}

}

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let num_agents = 3;

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(100);

let mut senders_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

let mut receivers_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

for id in 0..num_agents {

let (tx_agent, rx_agent) = mpsc::channel(100);

senders_map.insert(id, tx_agent);

receivers_map.insert(id, rx_agent);

}

let mut server = CentralServer::new(rx, senders_map.clone());

task::spawn(async move {

server.run().await;

});

for id in 0..num_agents {

let tx_clone = tx.clone();

task::spawn(async move {

let seed = id as u64;

agent_task(id, tx_clone, seed).await;

});

}

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(5)).await;

}

async fn agent_task(agent_id: usize, tx: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>, seed: u64) {

let mut rng = StdRng::seed_from_u64(seed); // Use a seedable RNG that is Send

loop {

let parameters = vec![rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0); 10];

let update = ModelUpdate { agent_id, parameters };

tx.send(update.clone()).await.unwrap();

println!("Agent {} sent parameters to Central Server", agent_id);

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

}

}

The program begins by initializing channels for communication between the central server and agents. The CentralServer struct receives model updates from agents through a shared receiver and distributes aggregated updates to all agents using dedicated sender channels. Each agent runs in its own asynchronous task, generating random model updates using a seedable random number generator (StdRng) to simulate local training. These updates are sent to the central server, which logs the received updates and broadcasts the aggregated parameters back to all agents. The asynchronous design, powered by tokio, allows the server and agents to operate concurrently without blocking, enabling efficient communication and real-time updates.

The code establishes a federated learning environment by defining a ModelUpdate struct to represent messages exchanged between agents and the central server, containing agent IDs and model parameters. The CentralServer struct handles receiving updates from agents, performing parameter aggregation (e.g., averaging), and broadcasting aggregated parameters back to agents. The main function initializes communication channels, spawns the central server as an asynchronous task, and launches individual agents, each running asynchronously. Within the agent task function, agents simulate generating model updates, send them to the central server, receive aggregated parameters, and update their local models, incorporating delays to mimic realistic training intervals. This implementation highlights the use of Rust's tokio and serde for efficient asynchronous communication, demonstrating a scalable and extensible framework for federated learning, with the ModelUpdate struct serving as a flexible foundation for more complex operations.

This implementation illustrates key aspects of FDRL, including decentralized training, aggregation, and communication efficiency. The central server acts as a global aggregator, mimicking the role of a federated learning coordinator, while agents represent individual learning entities with localized models. The use of asynchronous programming models, such as those provided by tokio, highlights the importance of efficient communication in FDRL systems to handle large-scale, distributed environments. Although the simulation uses randomly generated parameters for simplicity, the framework can be extended to incorporate real-world machine learning models and privacy-preserving techniques, making it a robust starting point for building scalable FDRL systems.

Developing a basic FDRL simulation builds upon the federated environment setup by enabling multiple agents to interact with either shared or distributed environments and coordinate their learning processes through decentralized communication. The simulation workflow begins with each agent interacting with its local environment, gathering experiences that are then used to update its policy parameters through local training. Periodically, agents send their updated model parameters to a central server, which aggregates these updates into a global model. This global model is subsequently broadcasted back to the agents, allowing them to synchronize their local policies and leverage collective learning to improve their performance.

In Rust, this simulation can be implemented by extending the federated environment example with additional functionalities that support environment interaction and policy updates. Each agent runs in its own asynchronous task, collecting data, training locally, and communicating with the central server. The central server aggregates the model updates from agents, forming a global policy, and distributes it back to them. This approach demonstrates how Rust's concurrency model, supported by tokio for asynchronous programming and serde for data serialization, facilitates the creation of a collaborative learning system.

The code below implements a simplified FDRL framework where multiple agents asynchronously communicate with a central server to exchange model updates. Each agent performs local training, updates its parameters, and sends these updates to the central server. The central server aggregates the updates, computes the global model, and broadcasts it back to all agents for synchronization. The communication is managed using Rust's tokio library for asynchronous operations and serde for data serialization. This framework demonstrates a collaborative learning setup that can be scaled for distributed systems.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0.93"

tokio = { version = "1.42", features = ["full"] }

serde = { version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

rand = { version = "0.8", features = ["std_rng"] }

use tokio::sync::mpsc;

use serde::{Serialize, Deserialize};

use tokio::task;

use std::collections::HashMap;

use rand::rngs::StdRng;

use rand::SeedableRng;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the message structure for parameter updates

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

struct ModelUpdate {

agent_id: usize,

parameters: Vec<f32>, // Simplified parameter representation

}

// Define the central server structure

struct CentralServer {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>,

}

impl CentralServer {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>) -> Self {

CentralServer { receiver, senders }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

let mut aggregated_parameters: Vec<f32> = Vec::new();

let mut count = 0;

while let Some(update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Central Server received update from Agent {}", update.agent_id);

if aggregated_parameters.is_empty() {

aggregated_parameters = update.parameters.clone();

} else {

for (i, param) in update.parameters.iter().enumerate() {

aggregated_parameters[i] += param;

}

}

count += 1;

// Once updates from all agents are received, aggregate and broadcast

if count == self.senders.len() {

for param in aggregated_parameters.iter_mut() {

*param /= self.senders.len() as f32;

}

println!("Central Server aggregated parameters: {:?}", aggregated_parameters);

// Broadcast aggregated parameters back to agents

for (&agent_id, sender) in &self.senders {

let message = ModelUpdate {

agent_id,

parameters: aggregated_parameters.clone(),

};

sender.send(message).await.unwrap();

println!("Central Server sent aggregated parameters to Agent {}", agent_id);

}

// Reset for next round

aggregated_parameters = Vec::new();

count = 0;

}

}

}

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let num_agents = 3;

// Create channels for agents to send updates to the central server

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(100);

// Create channels for the central server to send updates back to agents

let mut senders_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

let mut receivers_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

for id in 0..num_agents {

let (tx_agent, rx_agent) = mpsc::channel(100);

senders_map.insert(id, tx_agent);

receivers_map.insert(id, rx_agent);

}

// Initialize the central server

let mut server = CentralServer::new(rx, senders_map.clone());

// Spawn the central server task

task::spawn(async move {

server.run().await;

});

// Initialize and spawn agent tasks

let mut handles = vec![];

for id in 0..num_agents {

let tx_clone = tx.clone();

let mut rx_agent = receivers_map.remove(&id).unwrap();

let handle = task::spawn(async move {

agent_task(id, tx_clone, &mut rx_agent).await;

});

handles.push(handle);

}

// Wait for all agent tasks to complete

for handle in handles {

handle.await.unwrap();

}

}

// Define a simple agent task

async fn agent_task(agent_id: usize, tx: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>, rx: &mut mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>) {

// Initialize local model parameters randomly with a send-able RNG

let mut rng = StdRng::from_entropy();

let mut parameters: Vec<f32> = (0..10).map(|_| rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0)).collect();

for _ in 0..5 { // Limit number of iterations for demonstration

// Simulate training by updating parameters

for param in parameters.iter_mut() {

*param += rng.gen_range(-0.01..0.01); // Small random updates

}

println!("Agent {} updated parameters: {:?}", agent_id, parameters);

// Send updated parameters to the central server

let update = ModelUpdate { agent_id, parameters: parameters.clone() };

tx.send(update.clone()).await.unwrap();

println!("Agent {} sent parameters to Central Server", agent_id);

// Wait for aggregated parameters from the central server

if let Some(agg_update) = rx.recv().await {

println!("Agent {} received aggregated parameters: {:?}", agent_id, agg_update.parameters);

// Update local model parameters based on aggregated parameters

parameters = agg_update.parameters;

}

// Wait before next update

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

}

}

The code implements FDRL system where agents communicate asynchronously with a central server to collaboratively train their models. The ModelUpdate struct defines the structure for updates exchanged between agents and the server, encapsulating the agent's ID and its parameter updates. The CentralServer struct manages this communication, with a receiver to collect updates from agents and senders to distribute aggregated parameters back. Its run method aggregates the updates by averaging and broadcasts the results to all agents. In the main function, communication channels are established, and both the central server and agent tasks are initialized and executed asynchronously. Each agent task simulates training by randomly updating its local parameters, sending these updates to the server, and incorporating the aggregated parameters into its local model upon receipt. Delays are introduced to simulate realistic training cycles, demonstrating how agents and the server collaborate asynchronously to achieve global learning objectives.

This code illustrates fundamental concepts of FDRL, such as decentralized learning, aggregation, and communication efficiency. The asynchronous task-based design ensures scalability by allowing multiple agents and the server to operate concurrently without blocking. The use of parameter aggregation via averaging mirrors real-world federated learning practices, making it applicable for scenarios like edge computing and multi-agent systems. However, the framework can be further enhanced by incorporating techniques like differential privacy for secure parameter exchanges, gradient compression for reducing communication overhead, and weighted aggregation for handling heterogeneous agents. This example serves as a foundational template for building scalable, privacy-preserving FDRL systems in Rust.

To provide a more concrete example, the following Rust code showcases a simplified FDRL application where multiple agents collaboratively train their policies in a federated environment. The FDRL represents a decentralized learning paradigm where multiple agents independently train on local environments and periodically share their model updates with a central server. The central server aggregates these updates and redistributes a unified model to all agents. This approach leverages distributed data while ensuring privacy, as raw data remains on local devices. In the provided code, each Agent simulates a reinforcement learning actor by performing local training and periodically sharing its updated model parameters with a CentralServer for aggregation and redistribution.

[dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1.42", features = ["full"] }

serde = { version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

rand = { version = "0.8", features = ["std_rng"] }

tch = "0.12.0"

use tokio::sync::mpsc;

use serde::{Serialize, Deserialize};

use tokio::task;

use std::collections::HashMap;

use tch::{Device, nn};

use rand::Rng;

use tch::nn::OptimizerConfig;

// Define the message structure for parameter updates

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

struct ModelUpdate {

agent_id: usize,

parameters: Vec<f32>, // Simplified parameter representation

}

// Define the central server structure

struct CentralServer {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>,

}

impl CentralServer {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>) -> Self {

CentralServer { receiver, senders }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

let mut aggregated_parameters: Vec<f32> = Vec::new();

let mut count = 0;

while let Some(update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Central Server received update from Agent {}", update.agent_id);

if aggregated_parameters.is_empty() {

aggregated_parameters = update.parameters.clone();

} else {

for (i, param) in update.parameters.iter().enumerate() {

aggregated_parameters[i] += param;

}

}

count += 1;

// Once updates from all agents are received, aggregate and broadcast

if count == self.senders.len() {

for param in aggregated_parameters.iter_mut() {

*param /= self.senders.len() as f32;

}

println!("Central Server aggregated parameters: {:?}", aggregated_parameters);

// Broadcast aggregated parameters back to agents

for (&agent_id, sender) in &self.senders {

let message = ModelUpdate {

agent_id,

parameters: aggregated_parameters.clone(),

};

sender.send(message).await.unwrap();

println!("Central Server sent aggregated parameters to Agent {}", agent_id);

}

// Reset for next round

aggregated_parameters = Vec::new();

count = 0;

}

}

}

}

// Define the Agent structure

struct Agent {

id: usize,

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>,

vs: nn::VarStore,

#[allow(dead_code)]

actor: nn::Sequential,

#[allow(dead_code)]

optimizer: nn::Optimizer,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(id: usize, receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>) -> Self {

// Initialize Variable Store

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::cuda_if_available());

let root = vs.root();

// Define a simple neural network for the Actor

let actor = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&root / "layer1", 4, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&root / "layer2", 128, 2, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.tanh()); // Actions are normalized between -1 and 1

let optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

Agent { id, receiver, sender, vs, actor, optimizer }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

loop {

// Simulate local training: update parameters randomly

self.local_training().await;

// Send updated parameters to the central server

let parameters = self.get_parameters();

let update = ModelUpdate { agent_id: self.id, parameters };

self.sender.send(update.clone()).await.unwrap();

println!("Agent {} sent parameters to Central Server", self.id);

// Wait to receive aggregated parameters from the central server

if let Some(agg_update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Agent {} received aggregated parameters: {:?}", self.id, agg_update.parameters);

self.update_parameters(agg_update.parameters).await;

}

// Wait before next training iteration

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await;

}

}

async fn local_training(&mut self) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

tch::no_grad(|| {

for mut var in self.vs.variables() {

let delta: f32 = rng.gen_range(-0.01..0.01);

// We create a new tensor and copy the values, avoiding in-place add on a leaf var with grad

let new_val = var.1.f_add_scalar(delta as f64).unwrap();

var.1.copy_(&new_val);

}

});

println!("Agent {} performed local training", self.id);

}

fn get_parameters(&self) -> Vec<f32> {

let mut params = Vec::new();

for (_, var) in self.vs.variables() {

let size = var.size();

let numel: i64 = size.iter().product();

let mut buffer = vec![0f32; numel as usize];

// Convert numel to usize before passing it to copy_data

var.to_device(Device::Cpu).copy_data(&mut buffer, numel as usize);

params.extend(buffer);

}

params

}

async fn update_parameters(&mut self, aggregated_params: Vec<f32>) {

tch::no_grad(|| {

let mut start_idx = 0;

for mut var in self.vs.variables() {

var.1.requires_grad_(false); // Ensure no gradient tracking

// Determine the shape and number of elements for var.1

let shape = var.1.size();

let numel: usize = shape.iter().map(|&dim| dim as usize).product();

if start_idx + numel <= aggregated_params.len() {

// Slice the flattened parameters for this particular variable

let new_tensor_data = &aggregated_params[start_idx..start_idx + numel];

// Create a 1D tensor from the data

let mut new_tensor = tch::Tensor::of_slice(new_tensor_data)

.to_device(tch::Device::cuda_if_available());

// Reshape the tensor using shape as a slice

new_tensor = new_tensor.view(shape.as_slice());

// Now copy is safe since shapes match

var.1.copy_(&new_tensor);

start_idx += numel;

}

}

});

println!("Agent {} updated local parameters with aggregated parameters", self.id);

}

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let num_agents = 3;

// Create channels for agents to send updates to the central server

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(100);

// Create channels for the central server to send updates back to agents

let mut senders_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

let mut receivers_map: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

for id in 0..num_agents {

let (tx_agent, rx_agent) = mpsc::channel(100);

senders_map.insert(id, tx_agent);

receivers_map.insert(id, rx_agent);

}

// Initialize the central server

let mut server = CentralServer::new(rx, senders_map.clone());

// Spawn the central server task

task::spawn(async move {

server.run().await;

});

// Initialize and spawn agent tasks

for id in 0..num_agents {

let tx_clone = tx.clone();

let rx_agent = receivers_map.remove(&id).unwrap();

task::spawn(async move {

let mut agent = Agent::new(id, rx_agent, tx_clone);

agent.run().await;

});

}

// Allow some time for communication and training

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(20)).await;

}

In this setup, agents train local models independently, using random updates to simulate reinforcement learning dynamics. They send their locally trained model parameters to the CentralServer via asynchronous message channels implemented using tokio::sync::mpsc. The CentralServer aggregates the updates, computes an average, and broadcasts the aggregated parameters back to all agents. The agents incorporate the aggregated parameters into their local models, ensuring convergence towards a globally optimal policy over successive rounds of communication and training. This cycle of local training, aggregation, and redistribution continues iteratively.

The code establishes a federated deep reinforcement learning environment where agents communicate asynchronously with a central server to collaboratively train their models. The ModelUpdate struct defines the format for exchanging parameter updates, including an agent's ID and its parameter vector. The CentralServer struct orchestrates communication by collecting updates via a receiver, aggregating them through averaging, and broadcasting synchronized updates back to agents through its senders. Each Agent has an ID, communication channels, an actor network representing its policy, and an optimizer for local training. The agent's run method manages the learning loop, where local training updates are performed, parameters are sent to the server, and aggregated parameters are received to refine the local model. In the main function, communication channels are initialized, and both the server and agent tasks are executed concurrently using asynchronous programming. Agent tasks mimic realistic training by making small random updates to parameters, exchanging updates with the server, and introducing delays to simulate training intervals, enabling collaborative learning across the system.

The implementation demonstrates the power of tokio for asynchronous communication, enabling scalable and non-blocking operations among agents and the central server. The use of tch for model management allows seamless handling of neural network weights and operations. Key challenges in FDRL include ensuring efficient parameter aggregation, maintaining communication overhead within limits, and addressing issues like model drift due to non-i.i.d data distributions across agents. The provided code serves as a foundational framework for more complex scenarios, such as integrating actual RL environments, reward functions, or advanced optimization strategies.

Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning represents a significant advancement in the field of reinforcement learning, addressing critical challenges related to data privacy, scalability, and decentralized learning. By integrating federated learning principles with reinforcement learning algorithms, FDRL enables the training of intelligent agents in distributed environments without the need for centralized data aggregation. This paradigm is particularly beneficial in applications where data privacy is paramount, computational resources are distributed, and real-time adaptability is essential.

In this introductory section, we explored the foundational aspects of FDRL, including its definition, mathematical framework, and key terminologies. We delved into the importance of FDRL in modern application domains such as edge computing, IoT, and multi-agent systems, highlighting its advantages over traditional centralized reinforcement learning approaches. Furthermore, we addressed the inherent challenges in FDRL, such as data heterogeneity, communication efficiency, privacy concerns, and scalability, providing insights into the complexities that must be navigated to implement effective federated systems.

19.2. Mathematical Foundations of FDRL

Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) represents a powerful synthesis of federated learning and reinforcement learning, creating a framework where multiple agents can collaboratively learn policies while ensuring that sensitive data remains decentralized and private. At its core, FDRL addresses a fundamental challenge in modern AI: how to leverage distributed data and compute resources to train intelligent systems without compromising privacy or efficiency. Imagine a symphony orchestra where individual musicians (agents) practice their parts independently but periodically synchronize with the conductor (global model) to harmonize their efforts. This orchestration ensures both individual growth and collective coherence, much like how FDRL enables decentralized agents to align toward a shared goal.

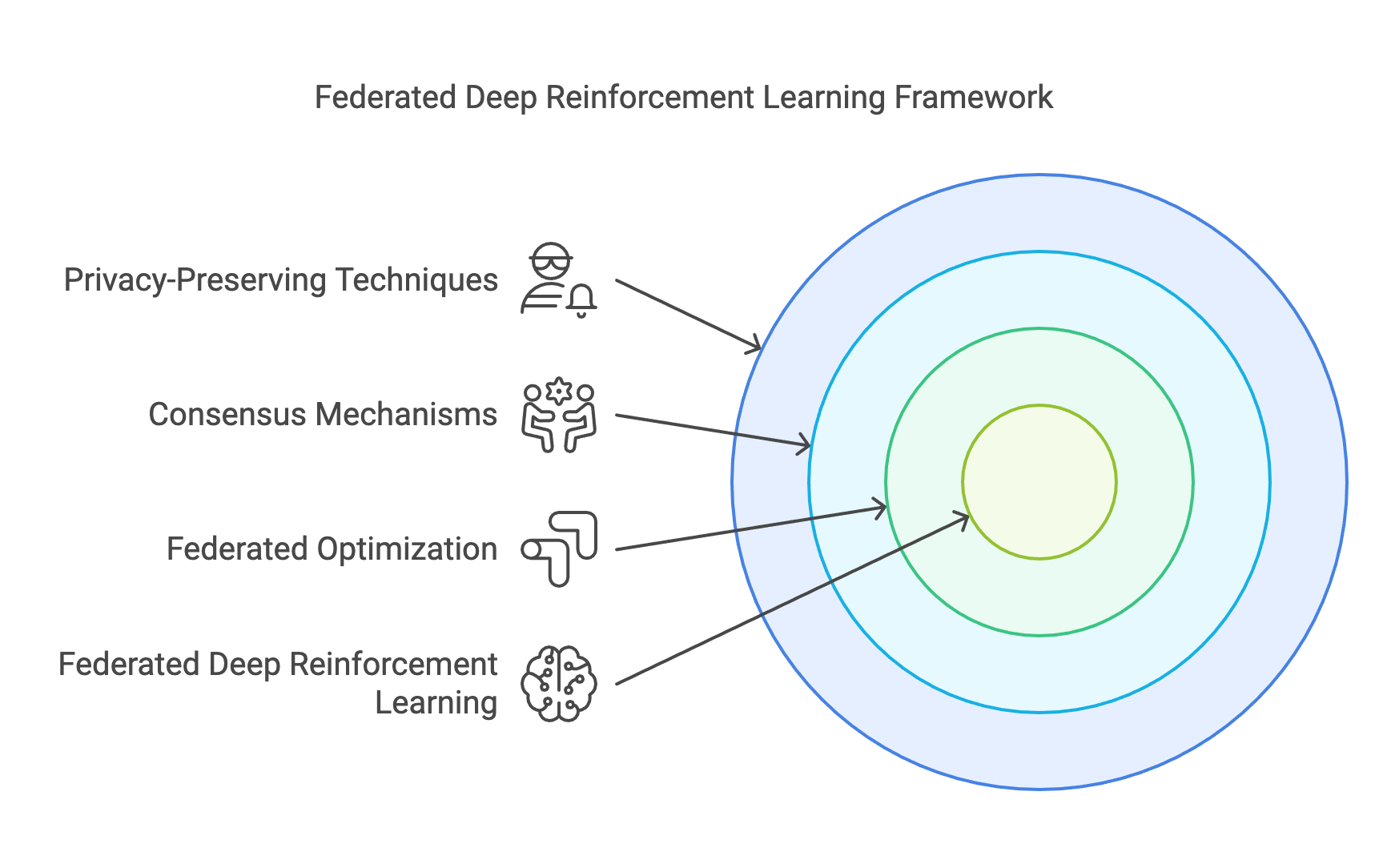

Figure 4: The code framework of FDRL.

The foundation of FDRL is anchored in three critical pillars: federated optimization, consensus mechanisms, and privacy-preserving techniques. Federated optimization serves as the backbone, allowing agents to independently train on local data while periodically sharing updates with a central server or peer network to improve the global policy. This approach eliminates the need for raw data transfer, akin to a decentralized brainstorming session where participants exchange only summaries of their ideas, preserving confidentiality while building on each other's insights.

Consensus mechanisms in FDRL play a vital role in aligning the diverse perspectives of distributed agents. These mechanisms ensure that the updates from individual agents are aggregated into a coherent global model, much like a team agreeing on a common strategy after considering individual contributions. The process must handle differing data distributions, computational capabilities, and even communication delays, making consensus both a technical challenge and a cornerstone of effective collaboration.

Privacy-preserving techniques elevate FDRL's relevance in domains where data sensitivity is paramount. By employing methods like differential privacy and secure multiparty computation, FDRL ensures that individual contributions remain anonymous and secure, even in adversarial settings. Picture a vault where everyone contributes pieces to a puzzle, but no single participant can access the complete picture. This ability to safeguard individual privacy while enabling collective intelligence is one of FDRL's most compelling features.

This section delves into these foundational elements with depth and clarity, offering advanced insights into the practical challenges and trade-offs in federated settings. One significant aspect of FDRL is managing data heterogeneity—when agents operate in environments with vastly different data distributions. Addressing this requires balancing local adaptability with global coherence, much like crafting a quilt where each patch represents unique local patterns yet contributes to a unified design.

At the core of FDRL is the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm, which facilitates the aggregation of locally trained models into a global model. The mathematical formulation of FedAvg is straightforward yet powerful, leveraging distributed gradient descent with periodic synchronization.

Consider $K$ agents, each with local parameters $\theta_k$ and a local objective function $L_k(\theta)$. The global objective is defined as:

$$L(\theta) = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K L_k(\theta).$$

FedAvg operates by performing local updates at each agent using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD):

$$\theta_k^{t+1} = \theta_k^t - \eta \nabla L_k(\theta_k^t),$$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate. Periodically, the central server aggregates these updates to form the global model:

$$\theta^{t+1} = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \theta_k^{t+1}.$$

In the context of reinforcement learning, $L_k(\theta)$ often corresponds to policy or value function losses derived from local interactions with the environment. FedAvg can be adapted to aggregate policy gradients, enabling distributed policy optimization without sharing raw data.

Consensus mechanisms ensure synchronization among federated agents, facilitating the aggregation of local updates into a coherent global model. A common approach is to model agent interactions as a graph $G = (V, E)$, where $V$ represents the agents, and $E$ denotes the communication links. The update rule for decentralized consensus is:

$$\theta_k^{t+1} = \theta_k^t + \alpha \sum_{j \in \mathcal{N}_k} (\theta_j^t - \theta_k^t),$$

where $\mathcal{N}_k$ is the set of neighbors of agent $k$, and $\alpha$ is the step size. This iterative process aligns local models toward a common consensus, enabling federated optimization without a central server.

In Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL), preserving privacy is crucial as agents work with sensitive, localized data. Differential Privacy (DP) is one key technique that protects individual data by introducing noise to gradients or model parameters. This ensures that individual data points cannot be reconstructed from the updates. The noisy parameter update in DP can be expressed as:

$$\theta_k^{t+1} = \theta_k^t - \eta (\nabla L_k(\theta_k^t) + \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)),$$

where $\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$ is Gaussian noise with variance $\sigma^2$. This mechanism obfuscates specific details while retaining the general utility of the updates. Another technique is Secure Multiparty Computation (SMC), which ensures privacy during model aggregation by distributing the computation across multiple agents. Using methods like additive secret sharing, agents split their updates into shares and only provide partial information for aggregation. This ensures that no single agent gains access to the complete global model or sensitive data, safeguarding the privacy of local information. Together, DP and SMC offer robust solutions for privacy preservation in FDRL systems.

In FDRL, policy learning is inherently distributed. Each agent learns a local policy $\pi_k(a|s; \theta_k)$, which is optimized based on interactions with its local environment. Periodically, these local policies are aggregated to update the global policy:

$$\pi(a|s; \theta) = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \pi_k(a|s; \theta_k).$$

This approach allows agents to leverage shared knowledge while retaining the flexibility to specialize based on their local environments.

Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) introduces several trade-offs that require careful balancing to optimize performance. One major trade-off lies between communication costs and convergence rates. Frequent communication between agents and the central server accelerates convergence but incurs significant bandwidth overhead. To address this, adaptive communication schedules and model compression techniques can reduce communication frequency while maintaining reasonable convergence speeds. Another trade-off exists between model accuracy and privacy. Adding noise to gradients or parameters to preserve privacy, as in differential privacy, can degrade model accuracy. The challenge is to carefully tune the noise levels to strike a balance between protecting sensitive data and achieving acceptable performance.

Scalability and synchronization also present competing demands. While increasing the number of agents improves scalability and extends the system's capabilities, it complicates synchronization and can slow down convergence. Additionally, handling data heterogeneity poses unique challenges in FDRL, as agents often work with non-IID (non-identically distributed) data, leading to divergent local updates. To address this, weighted aggregation techniques can account for differences in data size across agents. For example, updates can be aggregated as:

$$\theta^{t+1} = \sum_{k=1}^K \frac{n_k}{\sum_{j=1}^K n_j} \theta_k^{t+1},$$

where $n_k$ is the number of samples at agent $k$. Another approach involves introducing regularization terms to align local updates with the global model, such as $L_k(\theta) = L_k(\theta) + \lambda \|\theta - \theta_k^t\|^2$, where $\lambda$ controls the strength of regularization. These strategies help mitigate the effects of data heterogeneity and improve the robustness of FDRL systems.

The Federated Averaging algorithm can be implemented in Rust using asynchronous programming features provided by the tokio crate. Below is a Rust implementation of FedAvg tailored for reinforcement learning agents. The code demonstrates a collaborative learning setup where multiple agents perform localized training on their respective models and communicate with a central server to update and synchronize a shared global model. Each agent operates independently, updating its model using simulated local training dynamics, while the central server aggregates the agents' updates to create a unified global model. This process ensures decentralized training without direct data sharing, maintaining privacy and improving scalability.

[dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1.42", features = ["full"] }

serde = { version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

rand = { version = "0.8", features = ["std_rng"] }

use tokio::sync::mpsc;

use serde::{Serialize, Deserialize};

use tokio::task;

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::HashMap;

// Define the message structure for model updates

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

struct ModelUpdate {

agent_id: usize,

parameters: Vec<f32>,

data_size: usize, // Number of local samples (simulated)

}

// Define the Central Server structure

struct CentralServer {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>,

}

impl CentralServer {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>>) -> Self {

CentralServer { receiver, senders }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

// Initialize a global model with 10 parameters

let param_count = 10;

// Temporary storage for current round of updates

let mut updates: Vec<ModelUpdate> = Vec::new();

while let Some(update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Central Server received update from Agent {} with data_size: {}", update.agent_id, update.data_size);

// Store the update until we have all agent updates

updates.push(update);

// Once updates from all agents are received, aggregate and broadcast

if updates.len() == self.senders.len() {

// Perform weighted aggregation (FedAvg)

let total_data: usize = updates.iter().map(|u| u.data_size).sum();

// Initialize the aggregated parameters with zeros

let mut global_model = vec![0.0; param_count];

// Weighted sum

for u in &updates {

for (i, &p) in u.parameters.iter().enumerate() {

global_model[i] += p * (u.data_size as f32);

}

}

// Divide by total data to get weighted average

for param in global_model.iter_mut() {

*param /= total_data as f32;

}

println!("Global model updated (FedAvg): {:?}", global_model);

// Broadcast aggregated parameters back to agents

for (&agent_id, sender) in &self.senders {

let message = ModelUpdate {

agent_id,

parameters: global_model.clone(),

data_size: 0, // Not needed when sending global updates

};

sender.send(message).await.unwrap();

println!("Central Server sent global model to Agent {}", agent_id);

}

// Clear updates for next round

updates.clear();

}

}

}

}

// Define the Agent structure

struct Agent {

id: usize,

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>,

sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>,

local_model: Vec<f32>,

data_size: usize, // Simulated local dataset size

}

impl Agent {

fn new(id: usize, receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>, sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>) -> Self {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Initialize a local model with random parameters

let local_model = (0..10).map(|_| rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0)).collect();

// Simulate a data size for the agent. In a real scenario, this

// would represent how many local samples they have.

let data_size = rng.gen_range(50..200);

Agent { id, receiver, sender, local_model, data_size }

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

loop {

self.local_training().await;

// Send updated parameters to the central server, including data_size

let update = ModelUpdate {

agent_id: self.id,

parameters: self.local_model.clone(),

data_size: self.data_size,

};

self.sender.send(update).await.unwrap();

println!("Agent {} sent local model update", self.id);

// Wait to receive aggregated parameters from the central server

if let Some(global_update) = self.receiver.recv().await {

self.local_model = global_update.parameters.clone();

println!("Agent {} updated local model with global model", self.id);

}

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await;

}

}

async fn local_training(&mut self) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Simulate local training by small random perturbations to parameters

for param in self.local_model.iter_mut() {

*param += rng.gen_range(-0.01..0.01);

}

println!("Agent {} performed local training", self.id);

}

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let num_agents = 3;

// Create channels for server communication

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(100);

let mut senders: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Sender<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

let mut receivers: HashMap<usize, mpsc::Receiver<ModelUpdate>> = HashMap::new();

// Create per-agent channels

for id in 0..num_agents {

let (agent_tx, agent_rx) = mpsc::channel(100);

senders.insert(id, agent_tx);

receivers.insert(id, agent_rx);

}

// Initialize and spawn the central server

let mut server = CentralServer::new(rx, senders.clone());

task::spawn(async move {

server.run().await;

});

// Initialize and spawn agent tasks

for id in 0..num_agents {

let sender = tx.clone();

let receiver = receivers.remove(&id).unwrap();

let mut agent = Agent::new(id, receiver, sender);

task::spawn(async move {

agent.run().await;

});

}

// Allow some time for the simulation

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(10)).await;

}

The system now operates in iterative cycles that incorporate weighted federated averaging. Agents perform local training, adjusting their model parameters based on simulated updates. These updated parameters, along with the size of the local dataset (data_size), are sent asynchronously to the central server using tokio::sync::mpsc channels. The central server then aggregates these updates by computing a weighted average of the parameters, giving more influence to agents with larger local datasets. After deriving a global model that represents this weighted collective knowledge, the server broadcasts it back to the agents, ensuring all participants remain synchronized. This cyclical process fosters convergence toward a robust, globally beneficial policy.

The code implements a federated deep reinforcement learning (FDRL) simulation that closely mirrors the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm. The ModelUpdate structure now includes both model parameters and the data_size, encapsulating all the information needed for weighted aggregation. The CentralServer structure collects updates from agents, uses data_size to calculate a weighted average, and forms a global model that it sends back to each agent. Meanwhile, the Agent structure simulates local training and sends model updates tied to its local data size, then incorporates the global model upon receiving it. The main function sets up this entire system, initializing communication channels, spawning the central server as an asynchronous task, and starting multiple agents. As a result, the code supports efficient, concurrent, and asynchronous interactions in a federated environment where agents have varying data workloads.

This FDRL implementation, now incorporating weighted averaging, highlights how asynchronous communication in Rust’s tokio framework can manage complex, concurrent federated learning processes. Although the current setup still simulates training and data distributions, the inclusion of data_size sets the stage for more realistic federated scenarios, where agents hold differently sized datasets and thus have different impacts on the global model. Future enhancements could involve integrating real reinforcement learning tasks, refining communication strategies, and exploring more sophisticated aggregation methods. The resulting framework provides a strong foundation for investigating decentralized learning, accommodating data heterogeneity, and testing scalability in FDRL systems.

This section delved into the mathematical foundations of FDRL, exploring optimization algorithms, consensus mechanisms, and privacy-preserving techniques. The practical implementation of Federated Averaging in Rust highlighted how these concepts translate into actionable code, emphasizing Rust's capabilities for building efficient, scalable, and privacy-aware FDRL systems. As we progress, these foundations will serve as the bedrock for tackling advanced algorithms and real-world applications in federated reinforcement learning.

19.3. Core Algorithms and Paradigms in FDRL

Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) revolutionizes the reinforcement learning paradigm by extending it to decentralized, distributed systems. In traditional reinforcement learning, agents often rely on a centralized framework where data and computational resources converge in a single location. FDRL disrupts this model by empowering multiple agents to independently interact with their local environments, learn optimal policies, and collaboratively contribute to a shared global objective—all while maintaining the confidentiality of their local data. This innovation bridges the growing need for intelligent systems that are both scalable and privacy-preserving, making FDRL a cornerstone of modern AI for distributed applications.

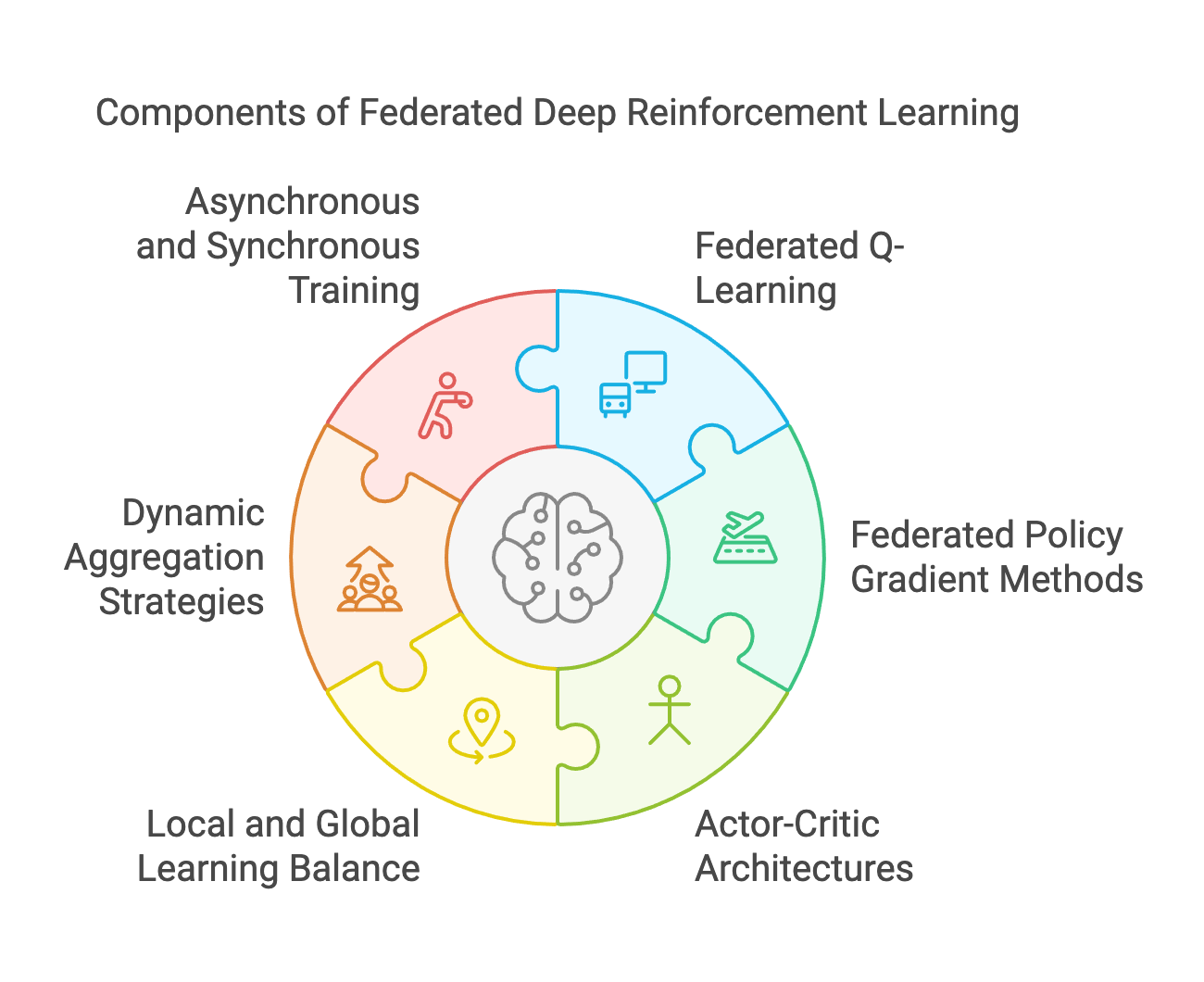

Figure 5: Key components of FDRL model.

At its heart lies the adaptation of traditional reinforcement learning methods to federated settings. Federated Q-Learning brings the classic value-based learning approach into the decentralized domain, allowing agents to independently estimate value functions while periodically synchronizing with a global model. Similarly, Federated Policy Gradient methods refine the policy optimization process for distributed environments, enabling agents to collaboratively improve their policies through gradient aggregation without direct access to others’ data. Building on these approaches, Actor-Critic architectures take center stage in FDRL, combining value-based and policy-based methods to optimize both the policy (actor) and value function (critic) in a federated context. These architectures are particularly well-suited for complex environments, where the interplay between local and global learning objectives demands nuanced coordination.

FDRL also introduces conceptual strategies that address the unique challenges of decentralized learning. Balancing local and global learning is one of the most critical considerations. Each agent must optimize its policy based on localized interactions while ensuring that these updates align with the global model. This balance often requires dynamic aggregation strategies, which weigh individual contributions based on factors like data quality, environment diversity, or computational capabilities. Additionally, the choice between asynchronous and synchronous training paradigms presents another pivotal trade-off. Synchronous training provides consistency by aggregating updates at fixed intervals but risks bottlenecks due to slower agents. Asynchronous training, on the other hand, allows agents to update the global model independently, fostering efficiency but introducing challenges such as stale updates and coordination complexities.

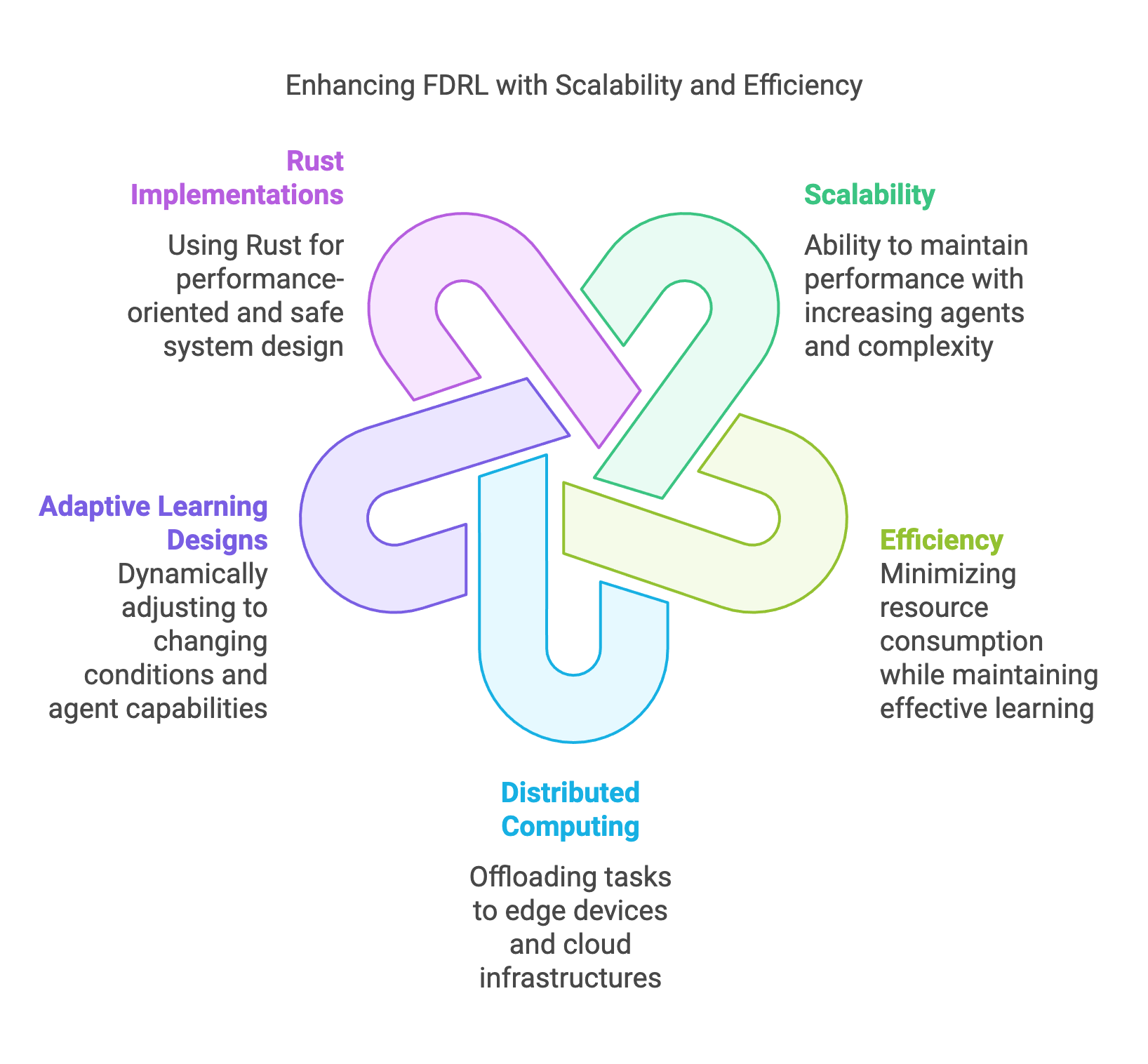

To translate these theoretical concepts into actionable knowledge, this chapter concludes with a comprehensive practical implementation of a Federated Policy Gradient algorithm using Rust. Leveraging the tch-rs crate for tensor operations, the implementation demonstrates how to build robust, scalable FDRL systems that handle distributed learning tasks effectively. Rust’s emphasis on safety, concurrency, and performance makes it an ideal language for such applications, enabling developers to write high-performance code that is both reliable and efficient.

By exploring the intricacies of FDRL algorithms, learning paradigms, and practical implementations, this chapter equips you with the tools to design advanced decentralized learning systems. Whether applied to autonomous vehicles, distributed robotics, or smart infrastructure, FDRL represents a transformative approach to collaborative intelligence, unlocking new possibilities for AI in decentralized, privacy-sensitive domains.

Federated Q-Learning adapts the Q-Learning algorithm to a federated setting, where agents independently update their Q-values based on local experiences while periodically aggregating updates to form a global Q-table.

The standard Q-Learning update rule for an agent $k$ is:

$$Q_k(s, a) \leftarrow Q_k(s, a) + \alpha \left[ r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q_k(s', a') - Q_k(s, a) \right],$$

where:

$s$ and $s'$ are the current and next states,

$a$ and $a'$ are the current and next actions,

$r$ is the reward,

$\alpha$ is the learning rate,

$\gamma$ is the discount factor.

In a federated setting, each agent computes local Q-value updates, and these updates are aggregated periodically to form a global Q-table:

$$Q(s, a) = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K Q_k(s, a).$$

This global Q-table is broadcasted back to agents, ensuring that their local Q-values benefit from the collective learning across all agents.

Policy gradient methods in federated environments optimize policies parameterized by $\theta$ based on the expected return:

$$J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \gamma^t r_t \right].$$

The gradient of the objective, $\nabla J(\theta)$, is approximated using sampled trajectories:

$$\nabla J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=0}^T \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) R_t,$$

where $R_t$ is the return from time $t$.

In a federated setting, each agent computes local policy gradients:

$$\nabla J_k(\theta) = \frac{1}{T_k} \sum_{t=0}^{T_k} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t | s_t) R_t.$$

These gradients are aggregated to update a global policy:

$$\theta \leftarrow \theta + \eta \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \nabla J_k(\theta),$$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate.

Actor-Critic methods combine the strengths of policy gradient (actor) and value-based methods (critic). In a federated context, each agent maintains local actor and critic networks:

Actor: $\pi_\theta(a | s)$,

Critic: $V_w(s)$, parameterized by $w$.

The actor’s policy is updated using:

$$\nabla J_k(\theta) = \mathbb{E} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a | s) A_k(s, a) \right],$$

where $A_k(s, a) = r + \gamma V_w(s') - V_w(s)$ is the advantage.

The critic updates its value function parameters www using:

$$w \leftarrow w - \alpha \nabla_w \left( r + \gamma V_w(s') - V_w(s) \right)^2.$$

Periodically, agents share and aggregate their actor and critic parameters to form global updates, facilitating collaborative learning.

Traditional reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms require significant adaptation to function effectively in federated settings, as they must account for decentralized data and the need for efficient aggregation. In federated Q-learning, for instance, local Q-values are periodically aggregated into a global Q-table, enabling distributed learning across multiple agents. Policy gradient methods are adapted by averaging gradients calculated locally by agents, optimizing a shared global policy. Similarly, actor-critic methods in federated settings involve synchronizing actor and critic parameters across agents, a process that must be carefully managed to reduce communication overhead while maintaining model performance.

The FDRL emphasizes a balance between local learning, where agents optimize their policies based on locally observed data, and global learning, which integrates these updates into a unified global model. This balance is achieved through strategies such as weighted aggregation, which considers the volume of data available at each agent, and regularization techniques that align local models with the global policy. Training paradigms in FDRL can be synchronous, where updates are aggregated at fixed intervals to ensure consistency but may result in delays due to slower agents, or asynchronous, where agents update the global model independently, improving efficiency but risking stale updates. These adaptations ensure FDRL systems are both effective and scalable in decentralized environments.

The following Rust implementation demonstrates a federated Actor-Critic algorithm, leveraging the tch-rs crate for tensor operations and tokio for asynchronous communication. In this FDRL, multiple agents, typically located in distributed environments, collaboratively learn a shared policy or value function without directly sharing their local data. This approach is particularly useful in scenarios where privacy, communication efficiency, or data heterogeneity are key concerns, such as in IoT networks, autonomous systems, or healthcare applications. By leveraging the power of DRL for decision-making and federated learning for decentralized training, FDRL allows agents to benefit from collective intelligence while maintaining their autonomy and privacy.

[dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1.42", features = ["full"] }

serde = { version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

rand = { version = "0.8", features = ["std_rng"] }

tch = "0.12.0"

use tokio::sync::mpsc;

use tch::{nn};

use serde::{Serialize, Deserialize};

use rand::{Rng, SeedableRng};

use rand::rngs::StdRng;

// Define model parameters for actor and critic

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Clone, Debug)]

struct ModelParams {

actor_params: Vec<f32>,

critic_params: Vec<f32>,

}

// Central server structure for federated aggregation

struct CentralServer {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelParams>,

senders: Vec<mpsc::Sender<ModelParams>>,

global_actor: Vec<f32>,

global_critic: Vec<f32>,

}

impl CentralServer {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelParams>, senders: Vec<mpsc::Sender<ModelParams>>) -> Self {

let global_actor = vec![0.0; 10]; // Initialize actor parameters

let global_critic = vec![0.0; 10]; // Initialize critic parameters

CentralServer {

receiver,

senders,

global_actor,

global_critic,

}

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

while let Some(params) = self.receiver.recv().await {

// Aggregate actor and critic parameters

for (i, param) in params.actor_params.iter().enumerate() {

self.global_actor[i] += param / self.senders.len() as f32;

}

for (i, param) in params.critic_params.iter().enumerate() {

self.global_critic[i] += param / self.senders.len() as f32;

}

// Broadcast updated global parameters

for sender in &self.senders {

sender.send(ModelParams {

actor_params: self.global_actor.clone(),

critic_params: self.global_critic.clone(),

})

.await

.unwrap();

}

}

}

}

// Define agent structure

struct Agent {

id: usize,

sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelParams>,

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelParams>,

#[allow(dead_code)]

actor: nn::Linear,

#[allow(dead_code)]

critic: nn::Linear,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(

id: usize,

sender: mpsc::Sender<ModelParams>,

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ModelParams>,

vs: &nn::Path,

) -> Self {

let actor = nn::linear(vs / "actor", 4, 10, Default::default());

let critic = nn::linear(vs / "critic", 4, 10, Default::default());

Agent {

id,

sender,

receiver,

actor,

critic,

}

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

loop {

let mut rng = StdRng::from_entropy();

// Simulate local training

let actor_update: Vec<f32> = (0..10).map(|_| rng.gen_range(-0.01..0.01)).collect();

let critic_update: Vec<f32> = (0..10).map(|_| rng.gen_range(-0.01..0.01)).collect();

drop(rng);

// Send updates to central server

self.sender

.send(ModelParams {

actor_params: actor_update.clone(),

critic_params: critic_update.clone(),

})

.await

.unwrap();

// Receive aggregated parameters

if let Some(_params) = self.receiver.recv().await {

println!("Agent {} updated models with global parameters", self.id);

}

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(2)).await;

}

}

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel(10);

let mut senders = Vec::new();

let mut receivers = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..3 {

let (agent_tx, agent_rx) = mpsc::channel(10);

senders.push(agent_tx);

receivers.push(agent_rx);

}

let mut server = CentralServer::new(rx, senders.clone());

tokio::spawn(async move {

server.run().await;

});

for (id, receiver) in receivers.into_iter().enumerate() {

let sender = tx.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(tch::Device::Cpu);

let mut agent = Agent::new(id, sender, receiver, &vs.root());

agent.run().await;

});

}

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(10)).await;

}

In this FDRL, each agent independently interacts with its local environment to collect experience and update its local reinforcement learning model, such as a policy network or Q-value function. Periodically, the agents send their model parameters (e.g., gradients or weights) to a central server, which aggregates these updates to create a global model using techniques like weighted averaging. The aggregated global model is then redistributed to the agents, allowing them to align their learning processes while preserving data privacy. The FDRL framework balances the trade-off between local computation and global communication, enabling efficient learning across diverse environments while addressing issues like non-IID data, communication constraints, and privacy requirements.

This simplified FDRL implementation represents a significant step forward in distributed intelligent systems, enabling robust and privacy-preserving collaborative learning across diverse environments. Its decentralized approach allows agents to adapt policies based on heterogeneous experiences, fostering resilience and scalability in dynamic multi-agent systems. However, challenges such as dealing with non-IID data, communication inefficiencies, and adversarial robustness remain open research areas. Despite these hurdles, FDRL holds immense promise for real-world applications, such as autonomous vehicles, personalized healthcare, and smart grids, where cooperative learning under constraints is essential.

This implementation highlights the interplay between local and global learning in a federated Actor-Critic setting, demonstrating the practical application of theoretical concepts in FDRL.

19.4. Communication and Coordination Mechanisms in FDRL

Communication and coordination lie at the heart of Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) systems, serving as the critical glue that binds decentralized agents into a cohesive learning framework. In FDRL, where agents operate across distributed environments, the ability to efficiently exchange, aggregate, and apply model updates is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental enabler of collaborative intelligence. The decentralized nature of FDRL inherently amplifies the complexity of these interactions, requiring sophisticated communication protocols and coordination strategies to ensure robust and scalable learning systems.

Effective communication in FDRL is not just about transmitting data; it’s about ensuring that these exchanges occur efficiently, securely, and with minimal overhead. Agents often operate in environments with varying computational resources, network bandwidth, and latency. This diversity necessitates adaptive communication protocols that can handle such heterogeneity while maintaining synchronization across the system. Strategies such as gradient compression, sparse updates, and periodic synchronization help reduce bandwidth consumption without compromising model accuracy, much like optimizing a supply chain to ensure timely delivery of essential resources without unnecessary expenditure.

Coordination in FDRL takes this a step further, addressing the dynamic interplay between agents as they contribute to a shared learning objective. The challenge is to aggregate the diverse updates from agents—each influenced by their local environments—into a global model that is representative and actionable. This requires consensus mechanisms that can align individual contributions while mitigating the risks of conflicting updates or adversarial behavior. Robust coordination strategies ensure that the learning system remains stable even as agents drop out, fail, or experience communication disruptions, akin to maintaining harmony in a distributed orchestra where not all musicians may play simultaneously or perfectly.

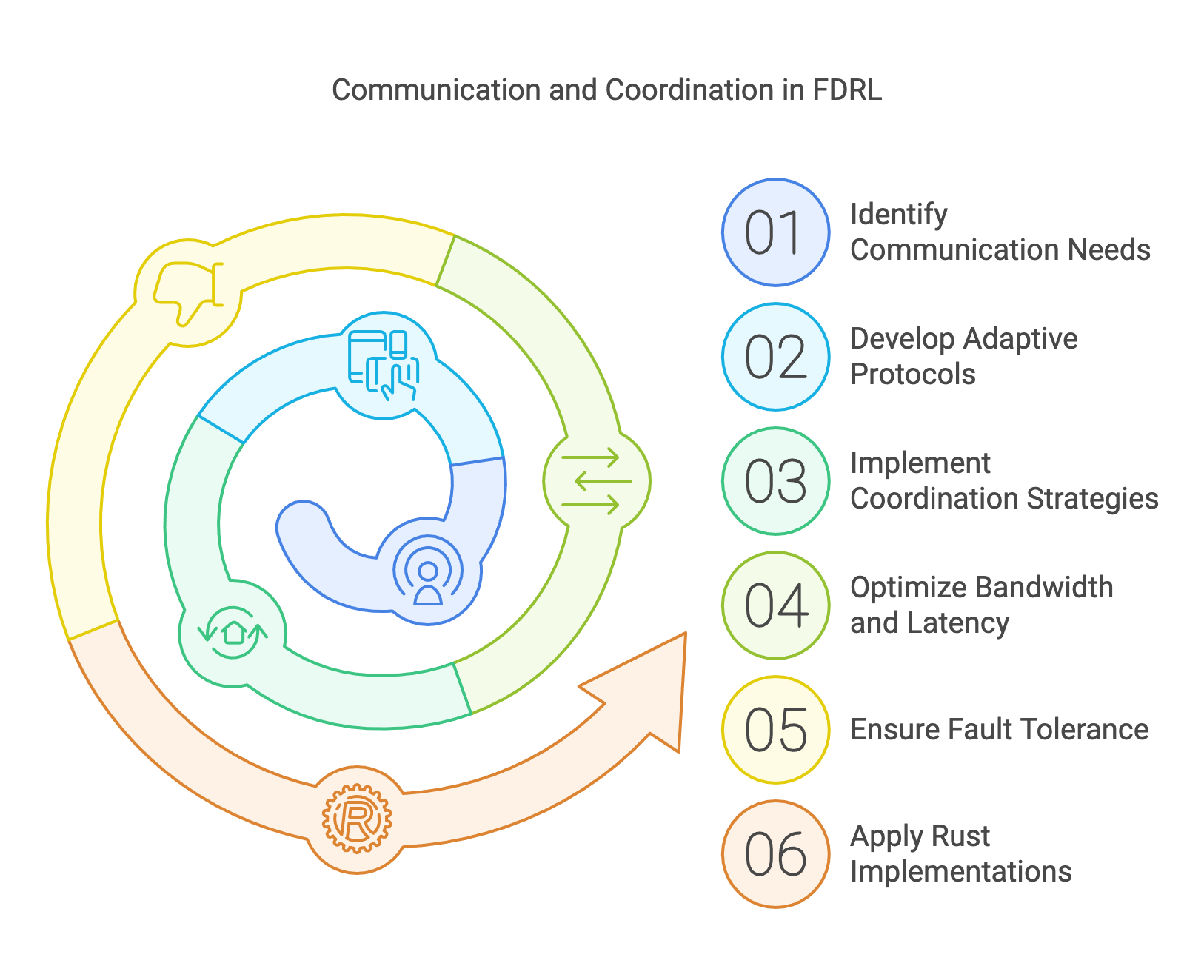

Figure 6: Development process of communication and coordination in FDRL.

This section delves deeply into the intricacies of these communication and coordination mechanisms, presenting advanced techniques for optimizing bandwidth, reducing latency, and ensuring fault tolerance. It examines the trade-offs between synchronous and asynchronous communication paradigms, highlighting their implications for scalability and convergence. Synchronous methods, though reliable, can be bottlenecked by slower agents, whereas asynchronous approaches, while faster, require careful handling of stale updates and potential inconsistencies. Techniques for handling failures and dropouts, such as resilient aggregation algorithms and redundancy in communication channels, are explored to ensure system robustness.

In FDRL, communication protocols govern the exchange of information between agents and the central server or directly among peer agents. These protocols aim to minimize communication overhead while preserving the fidelity of model updates.

Mathematically, let $\theta_k^t$ represent the local parameters of agent $k$ at iteration $t$. The communication protocol determines how these parameters are transmitted and aggregated into a global model $\theta^t$. A simple protocol is periodic aggregation $\theta^t = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \theta_k^t,$ where $K$ is the number of agents. Advanced protocols may involve sparse updates or compressed representations of $\theta_k^t$, reducing the size of transmitted data.

Bandwidth optimization is a crucial aspect of scaling Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) systems, as it minimizes communication overhead while maintaining learning performance. One effective technique is model compression, which reduces the size of model updates by quantizing parameters to lower precision. For example, parameters can be approximated as $\theta_k^{\text{compressed}} = \text{round}(\theta_k^t \cdot 2^b) / 2^bθ$, where $b$ represents the number of bits used for quantization. Another approach is sparse updates, which transmit only the significant changes in model parameters. These updates can be expressed as $\Delta_k^t = \{ \theta_k^t - \theta_k^{t-1} \mid |\theta_k^t - \theta_k^{t-1}| > \epsilon \}$, where $\epsilon$ is a threshold for sparsity, ensuring only meaningful updates are communicated. Additionally, gradient compression involves transmitting gradients instead of entire models, with techniques like top-$k$ sparsification or random sampling to further reduce data size. These methods collectively enable efficient communication, making FDRL systems more scalable and cost-effective.

Communication delays can significantly impact the convergence and performance of FDRL algorithms. If $d_k$ represents the delay for agent $k$, the global update $\theta^t$ may lag $\theta^t = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \theta_k^{t-d_k}.$ Asynchronous protocols mitigate this by allowing updates from agents to be aggregated without waiting for all agents:

$$\theta^t = \theta^{t-1} + \eta \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \nabla_k^{t-d_k}.$$

However, they must account for the risk of stale updates degrading learning dynamics.

In centralized communication, a server aggregates updates from agents and broadcasts the global model. This architecture simplifies coordination but introduces a bottleneck at the server and higher latency for agents farther from it.

In decentralized communication, agents exchange updates directly with their peers. This peer-to-peer model enhances scalability and fault tolerance but requires more sophisticated coordination mechanisms, such as consensus algorithms:

$$\theta_k^{t+1} = \theta_k^t + \alpha \sum_{j \in \mathcal{N}_k} (\theta_j^t - \theta_k^t),$$

where $\mathcal{N}_k$ represents the neighbors of agent $k$, and $\alpha$ is the consensus step size.